You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Activist Art’ category.

There are countless numbers to keep youth out of custodial settings, not least the threat of waste and violence jail brings.

In New York, one group is using art, photo and video as an alternative to jail. The Young New Yorkers intervenes at the juvenile court, and with sanction of the judge, allows children who are convicted of non-violent misdemeanours (turnstile jumping, graffiti, public disturbance) to embark on 3-day or 8-week art programs instead of heading to jail for 3 months or taking on a long community service stint.

The Young New Yorkers (YNY) uses art to help children imagine different lives for themselves, to conjure new possibilities for their neighbourhoods and to interrogate what community justice is and might be.

The Young New Yorkers (YNY) uses art to help children imagine different lives for themselves, to conjure new possibilities for their neighbourhoods and to interrogate what community justice is and might be.

Yesterday, YNY kicked off its #ArtNotJail campaign to raise funds for 2018’s programs.

“We are raising $10,000 to cover the costs of the next 6-months of public art projects,” writes YNY on its IndieGoGo crowdfunding page. “The next generation of Young New Yorkers will then use art to advocate for themselves, and advocate for a transformed criminal justice system.”

This humanising program listens to children, it opens up new potential and I’m a huge fan. Please consider giving to The Young New Yorkers.

Follow YNY on Facebook, Tumblr, Instagram, Twitter and Vimeo.

It’s unmistakable. That gazebo. That hexagonal cover to that picnic table. One needn’t notice the flowers, or even the poster, to the memory of Tamir Rice to recognize this utility structure as that under which the 12-year-old was murdered by Cleveland police. Even the bollards between us the viewer and the polygon shelter seem instantly familiar. For it was between those bollards and the gazebo that the cop car screeched to a halt, it’s door flew open and the first emerging officer shot Tamir dead. In the blink of an eye.

Tamir Rice was shot twice from less than 10 feet.

Back in 2014, as I watched the footage of Tamir Rice’s murder, I wondered then, why did the the cops mount the curb? Why did they bypass the pavement and careen the patrol car onto the grass? Into the park? Why the frantic invasion of a place for play and recreation? Why, given the clear lines of sight (evident both in this photo and in the murder footage) from a good distance away, did they not approach slowly and with caution?

“This court is still thunderstruck by how quickly this event turned deadly,” wrote Ronald B. Adrine, Cleveland Municipal Court Administrative and Presiding Judge in an Administrative Order on the case. “On the video, the zone car containing Patrol Officers Loehmann and Garmback is still in the process of stopping when Rice is shot.”

Misinterpreting a situation and mistaking a toy for a gun (in the case of Tamir Rice) — or mistaking anything handheld, or any motion toward a hip or a pocket (in the cases of thousands of others) — is the defense to which law enforcement turns repeatedly and, calamitously, the one which almost always exonerates them of their crimes.

This is a photo made by Alanna Styer. It is part of the project Where It Happened for which Styer visited and photographed 54 sites where people of color were slain at hands of law enforcement. In 2016, The Guardian reports, 1,093 people were killed by police officers in the United States.

“That is an average of three people a day,” writes Styer. “The incidents detailed in my archive span 50 years, from 1965 to 2015. This book documents only 54 of the tens of thousands of deaths that have happened over those 50 years.”

Mostly, the locations and details of those thousands of deaths aren’t known beyond the memory of friends and family, the accounts of the cops involved, and the reach of an investigation … if one occurred. Even then, the details remain contested. The majority of the places in Where It Happened are new to us, the audience. But Styer’s photo of the gazebo at Cudell Recreation Center is not new. It’s power rests, for me, in the fact that I have previous familiarity with the place through the news coverage and activism in the aftermath of Rice’s murder. I recognize the site. You probably do to. We might also recognize the site of Michael Brown’s death on that tarmac road with verges of short, thinning grass. We may recognize other sites of avoidable killings that made it to our news feeds and memory. We don’t, regrettably, recognize the vast majority of the tragic theaters to which Styer’s work speaks. There are too many.

Styer’s photo shifts our vantage point from the elevated view of the CCTV across the street and down to street level. Whereas previously the benches and the posts were rendered in the indistinguishable and out of focus action of the footage, they’re now brought into sharp focus. We see the underside of the gazebo roof, not the top. We’re provided a perspective from the asphalt where the cop car could have and should have been.

Being “in” this image, I only want to get out, of course. A world in which this wasn’t a murder site and you or I didn’t recognize it as such would be, inarguably, a better world. Specifically, I want to step back. The unnecessary haste with which officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback charged into this scene gloms onto this image. That unfathomable CCTV footage is this photo’s frame.

Loehmann and Garmback’s excessive urgency which escalated the event from zero to murder perverts Styer’s image. But it also makes it. This photo works upon and within the collective exposure we’ve had to that grainy footage. Styer’s tribute here isn’t working in isolation but in extension of previous visual feeds to which we’ve all been audience. This image is an intervention and it works to disrupt our (possibly passive) consumption of death. It revisits the space and time of an event in which Tamir Rice had, essentially, no agency. The stillness is terrifying. True, the image could be read simply as a visual description of a memorial but I argue that precisely because it grounds us between the CCTV camera and Rice’s swift execution, the photo re-activates both the event and our relation to it.

Acts of police brutality (or citizen brutality, e.g. George Zimmerman against Trayvon Martin) frequently spurn a battle of images — calls for the immediate release of dash cam footage; calls for body-cams; different photos are circulated and cast as sympathetic, or not, to the victim and the perpetrator; media outlets trawl the social media feeds of victims, perpetrators and associated individuals. Whether conscious or not, Styer is reacting to such frenzies. She is paying homage to the victims, months or years after the news story has passed and the casket lowered. Where It Happened is a dark type of pilgrimage but I feel Styer is making it in good faith and I argue she’s returning with images that are a positive contribution. Google Street View does not make imagery that is conscious or respectful (interestingly, it hovers above street level like CCTV, delivering a detached record). Cellphone images may carry as much, if not more, respect as Styer’s photographs and this might be based on a personal connection to the victim, but those amateur images are not made by an artists intent on publicly disseminating them and talking about the issues that forged them.

I admire and have reported on Josh Begley’s project Officer Involved which uses code to automatically render both satellite and Street View images of sites of deaths involving law enforcement. Thousands of sites. While the subject is the same Styer’s work is considerably different in tone and effect. If Begley manages to remind us of the scale of the problem then Styer’s work reminds us to recognize each depressing part of the problem. I can’t code or manipulate Google Maps API but I can walk, bike or drive to killing sites within my own city. Styer’s practice takes time and effort, away from the screen. In 2015, Teju Cole reflected upon the problem of the constant visibility of death. In Death In The Browser Tab, Cole recounts his discomfort with only *knowing* the death of Walter Scott through the infamous footage made by passerby Feidin Santana who was hiding in the bushes. Cole had the opportunity to visit North Charleston and with a friend he found the parking lot of Advance Auto Parts on Remount Road in which Officer Michael Slager first stopped Scott. Then Cole traced the steps of them both to the park in which Scott was slain.

“[…] being there also revealed, in the negative, the peculiarities of the video,” writes Cole, “peculiarities common to many videos of this kind: the combination of a passive affect and the subjective gaze, irregular lighting and poor sound, the amateur videographer’s unsteady grip and off-camera swearing. Taken by one person (or a single, fixed camera) from one point of view, these videos establish the parameters of any subsequent spectatorship of the event. The information they present is, even when shocking, necessarily incomplete. They [videos] mediate, and being on the lot helped me remove that filter of mediation somewhat.”

Styer’s practice is one response to the problematic mediation that Cole describes. Few of us can identify the problem, let alone respond to it. And just as Cole felt better for mindfully visiting the site of Walter Scott’s death, and just as Styer was compelled to visit 54 catastrophic sites, we can choose to seek out a different image. Away from local TV news and social media, death might become less abstract? The sheer scale of the issue might become overwhelming. It is. But are we citizens that feel or do we just talk about what it is to feel?

Are we inured and numbed by murder on our screens? Or are we compelled to act because of it? We can all easily research the institutional violence in our communities. Maybe some of us might be compelled to make pilgrimages of our own and to carve out time to think about the violence that always plays out on our streets before it is broadcasted into our homes. Styer took the time and she has mediated at these sites. Her image of the gazebo in which Tamir Rice was shot and killed gave me the opportunity to mediate. I am grateful for that.

Sometimes photographs are about what’s literally depicted. Sometimes the lessons in photographs are in the method by which they were made. In Where It Happened it is both.

–

Alanna Styer is currently crowdfunding a book of images from her series Where It Happened. Please consider supporting the production of the photobook, titled No Officers Were Injured In This Incident, by visiting Styer’s Kickstarter page.

Listen to a radio interview with Styer about the project and her goals for the book.

Cunliffe Street, Chorley

–

THE DARK FIGURE

The abuse might be going on in your town. Victims may be under coercion in your neighbourhood. Slaves and masters may be on your street. If that sounds far-fetched take a look at Amy Romer‘s project The Dark Figure* and you’ll learn that modern day slavery is diffuse throughout Britain. In recent years, cases of contemporary slavery, forced work and forced prostitution have been detected and prosecuted in villages, towns and cities in every region of the UK.

While modern day slavery is more prevalent in developing nations, it persists in (what we in the West prefer to call) advanced democratic nations. In December 2015, the UK Home Office estimated that there were 13,000 victims of slavery in Britain. The government referred to the 13,000 as “the dark figure” from which Romer’s documentary project derives its name.

Romer has travelled the UK photographing the streets that her research has uncovered as sites of slavery. I encourage you to learn more about the cases the project covers here:The Dark Figure*.

Romer wants “people to be reminded of somewhere they have lived or visited; somewhere they feel safe.” Do these places look familiar? For me these places look very familiar. I spent my formative years drinking at a pub at the bottom of Cunliffe Street, Chorley (pictured above). In recent weeks, I’ve travelled through Burnley, Batley and Blackburn. During the project, Romer discovered that two traffickers facing prosecution in Plymouth lived one street over from her.

The Dark Figure* is not an easy project to face. It is insistent on revealing the nastiness in our midst. It holds considerable visual dissonance for British audiences particularly. The act of documenting is, for Romer, a form of witness. I wonder to what degree this work propels us to learn more about the hidden issue? I wonder if any victims of contemporary slavery would ever see it? There’s a lot to unpack here, so I was happy Romer was willing to answer a few of my questions. Scroll on for our Q&A.

Ash Road, Horfield, Bristol

–

Q & A

I expect there are so many sites of imprisonment, slavery and abuse. How do you choose which to photograph?

Sadly, where I photograph is largely determined by and limited to which stories make the headlines. The 2015 Modern Slavery Act has made prosecutions of modern slavery and human trafficking easier to conduct and so we are starting to see an increase in cases and subsequent media attention. However, due to the sensitivity of the such cases, police give very limited information to press for the protection of both victims and suspects. So I’m having to initially search for the stories through the press and then do some digging of my own via the police, The White Pages and Google.

The problem is that many cases will never be known to the press, to me or to the public generally. First of all, it’s a hidden crime so uncovering it in the first place is a significant challenge, which takes a huge amount of police resources and social care. Secondly, victims are often scared of authority and have absolutely no trust to give. They’ve been mentally and/or physically controlled and threatened and are entirely dependent upon their ”employer” or “gang-master”, so even when victims are recovered it is likely they will run away from police or from care, and in a lot of cases, will return to their gang-master or get picked up by another. And we’ll never hear about it.

Putting aside the disturbing limitations, I knew early on that the project would only become effective once I was able to present an abundance of cases, becoming a kind of bleak directory of U.K. modern slavery cases. So as long as I’ve been able to piece together solid and reliable facts and have been able to get to the locations, I haven’t been too fussy about which stories I pick. It’s been more important that I capture the diversity of the problems that exist in the U.K., and to try to communicate that sense of abundance.

SOAS, Russell Square, London

Batley Field Hill, Batley, Kirklees

Bamfurlong Lane, Staverton, Cheltenham

–

What are the strengths and shortcomings of the image (as a medium) in the face of this issue?

The image of modern slavery is in most cases a troubling one. It’s hidden nature makes its reality very difficult to photograph. Instead, we tend to find images made to represent slavery, using actors or “symbols” of slavery such as hands tied with rope or a person trapped behind bars, which are not only inaccurate but are damaging to the understanding of the issue.

We may be exposed to photo stories of sex trafficking or labour exploitation in other countries, but we need to show people its right here in the UK with real pictures of real stories.

How do you describe the photographs?

There is nothing notable I can say about these images on their own. Perhaps that they are deliberately quiet. It is only when coupled with their stories that the pictures become something sinister, at which point the viewer can reconsider the world they thought was safe and familiar to them.

My ultimate goal is to spur a realisation in the audience that such crimes are likely to be happening much closer to home than they imagine.

Ringwood Road, Bournemouth

–

You explained in the Multimedia Week podcast that when you first approached people you had the idea, the will, but not something tangible to show; no images to share. Then you went out and just started making photographs to demonstrate your commitment and skill. Can you explain how and why that order of events helped or hindered the project.

There’s no right or wrong order of doing anything. But in my case, it had to happen in that order for me to understand the reality of the work I was proposing, and to then move forward with alternative ideas. But you never know with these things until you try. All it takes is speaking to the right person and you don’t know who that person is. (I still don’t!).

I was very lucky at the beginning and experienced a great deal of openness from Devon and Cornwall Police, which possibly led me to believe others would be just as forthcoming, but I came to realise this wouldn’t be the case, which I think is fair enough. Why trust me? The problem is, I’m still battling with the access I want – but this is all part of the job.

What I will say though, is that when I started making photographs I felt a huge sense of relief. Even for someone who relishes in research, I very much reached a point where I just needed to pick up a camera and go shoot.

This style of photography was very different than what I’m used to so it was a very interesting process for me and one which allowed me to continue research from a more positive perspective, as I started shaping my ideas and understanding of the subject through pictures.

Brougham Street, Burnley

Wentloog Avenue, Peterstone, South Wales

Farrier Road, Perivale, Ealing

–

Have you spoken to survivors of modern slavery?

I have. I had one guy reach out to me via Facebook having seen my project. We’re in conversation about working together long distance.

Previous to this, I had been trying to reaching out to NGOs for access to survivors, but had found that even after I had received a “yes” from a number of them, and months worth of email and phone communication, access would eventually be denied for the protection of the survivor(s). Of course, this is understandable and I would refuse to knowingly harm or prolong the process of recovery for any survivor, but I’m not always convinced the refusal has been a decision that has involved the survivor. I think NGOs sometimes struggle to appreciate the impact of a story told first-hand, compared with stories told by actors or through written case studies, which is what readers will usually experience. I’m not sure it’s enough to really reach people.

How do you assess public opinion in Britain on the issue of modern slavery?

“Modern slavery? What’s that!?”

The problem doesn’t just end with the lack of public awareness of modern slavery itself, but deepens with dangerous misunderstandings about the differences between terms such as “sex exploitation” and “sex work”, or “human trafficking” and “smuggling”, for example. These misunderstandings are only intensified when Europe finds itself at the centre of a migrant crisis, tangled with terms such as these that are freely distributed across the mass media.

Hathway Walk, Easton, Bristol

North Street, Bedminster, Bristol

Peckford Place, Brixton, London

–

Are the police doing good work?

There is a lack of consistency throughout the country. I have been largely based in Devon and Cornwall, where their Chief Constable Shaun Sawyer, is the UK policing lead for modern slavery, making the South-West surprisingly ahead of the game … for a game that is very far behind.

The 2015 Modern Slavery Act has certainly helped raise public consciousness and agencies are beginning to make good use of the Act. More victims are being identified than ever before. In 2015, 3,266 potential victims were identified and referred for support, a 40% increase on the previous year. There have been an increased number of proactive and reactive police investigations with an increased number of prosecutions and convictions.

But despite stand-out examples of good practice, there is still a lack of consistency in how law enforcement and criminal justice agencies deal with modern slavery. Training for police officers, investigators and prosecutors is patchy and sometimes completely absent. There is also an insufficient amount of intelligence about the nature and scale of modern slavery at regional, national and international level, which hampers the operational response and ability to build knowledge and learn from mistakes.

Union Street, Plymouth

–

Which organisations are doing work to advocate and illuminate the issue?

There are many organisations both big and small. It’s difficult to pick on individuals as I’ve become biased towards or against my own experiences, which doesn’t necessarily reflect the organisation as a whole.

I find it hard to truly know how impactful NGOS are. They seem to all be chasing money from the same pot and in some cases are actively working against each other for their own benefit.

But, to shine a positive light on something I know for sure: several NGOs act as “first responders” under the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), the government framework which grants 45-days of “reflection and recovery” for victims of human trafficking and modern slavery. In this inexcusably short period of time, victims are expected to give evidence of the horrors they have experienced to feared authorities so that “trained decision makers” can announce whether they are to be considered victims of trafficking. During this period, first responders provide housing and support for victims; so if by some miracle a victim feels compelled to recount their experiences to the police, it is surely all thanks to the outreach specialists supporting them.

On a less positive note: this 45-day period given by the government’s NRM, reflects the lack of understanding surrounding the issue. Even if an organisation has been made fully aware what their client has been through, if they do not wish to testify within 45-days, they are not considered victims and their support cannot continue. What will happen to the victim after 45-days? If they are not deported back to the country they were likely escaping from, they will probably end up back within the trafficking system. This is very challenging for support workers and NGOs and I salute all their efforts.

Spa Road, Bolton

Ford Park Road, Mutley, Plymouth

–

You’ve already made a newspaper. What else lies in store?

I think something I’ve had to learn the hard way is that it’s all very well making things for a project, but unless anyone sees it, what’s the point?

The reason I made the newspaper is because it would be cheaper to produce and easy to share with the community. People sometimes tell me it would look great in a book. Fine, but who is actually going to buy it other than photographers? In fact, who is going to fund it should be my first question, but it is not my first concern.

My focus for now and for the near future (at least) is to raise awareness. The work needs to be published, and the newspaper needs funding to be printed and shared in the community. It’s a slow game but I’m working on it.

How long do you intend to work on The Dark Figure*?

I’ve slowed the project for the moment as I’m currently in a state of transition, having recently moved to Vancouver, Canada with my partner for his work in science.

Saying that, I’ve had a few fresh ideas for The Dark Figure* since being over here, which I plan to follow up remotely. But naturally, I want to focus my attention towards Canada specific projects whilst I’m here for a few years.

There’s so much more work to be done and that’s partly why I felt comfortable placing The Dark Figure* to one side, as I have no doubt I’ll be exploring new avenues for it in the future.

Longworth Street, Preston

Portugal Street, Holborn, London

Wheelers Lane, Linton, Maidstone, Kent

–

What has been the reaction to The Dark Figure* so far?

From the people I’ve reached out to, the reaction has been very good. There have been flurries of people contacting me to buy the zine or the newspaper, mostly from the UK but also Europe, which is great.

There has been some valid criticism from news based editors explaining why they would find it difficult to publish, which I’m working on overcoming. My writing needs to be fact-checked in order to be publishable.

Also, outlets need to know I haven’t trespassed. I have never trespassed–there is no need. The Dark Figure* captures the surrounding neighbourhoods, not the actual property in question, and I’m always on the street.

Walker Street, Rawmarsh, Rotherham

–

Do you ever get overwhelmed? Depressed? Are you hopeful? Talk us through your self-care strategies.

I am cynical and can be full of doubt, all the time. But for me, these stories are about human survival, and despite being totally fascinated by it all, it’s what gives me hope and drives my work forward.

Tragedies exist everywhere, and I don’t think that’s a difficult idea to grasp. But what is difficult, is to believe that such tragedies are happening right in front of us. And I don’t just mean modern slavery. Domestic abuse, addiction, mental health issues and so on, are all issues that can largely exist behind closed doors. By attempting to shine a light onto a truth that otherwise may not be acknowledged, I am doing something useful and positive. It’s a self-care strategy in itself.

Saying that, the news can sometimes overwhelm me when I’m thinking specifically about this work. The migrant crisis. Immigration. I wonder whether the government’s efforts to “face up to modern day slavery” is just another way of deporting the unwanted. Europe is becoming more and more tangled with problems and I wonder what effect it will have on human trafficking, for example. 10,000 refugee children are missing. Where have they gone? Something tells my cynical mind, like all hidden tragedies, we won’t find out the easy way.

A sombre note on which to end. Thank you for sharing your work and thoughts, Amy.

Thank you, Pete.

–

Be sure to follow The Dark Figure* project on dedicated Twitter and Instagram feeds. Follow Amy Romer on Instagram and Twitter.

Smart Street, Longsight, Manchester

–

Later today, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announces the nominations for the 2017 Oscars. Ava DuVernay’s doc 13th is on the longlist and tipped to make the shortlist for Best Documentary*. 13th has, deservedly, got a lot of praise since its release in October, but there’s another documentary about the Prison Industrial Complex that came out in 2016 that I’d like to champion here.

The Prison In Twelve Landscapes, directed by Brett Story, is a film that, in many ways, retools the documentary format. It is a film about prison without ever going inside one (although the film closes with a monumental, slow-motion approach to the car-park of the citadel-like Attica Prison). It’s not up for a gong, which is a shame because everyone can benefit from its radical politics and creative verve.

Forcefully, The Prison In Twelve Landscapes rejects the common format of prison documentaries. You know, meet a character; set the broader context of incarceration; chart the character’s life; establish a moment in which fortunes changed for the worst; define the injustice; imagine a different future for the main character and possibly thousands or millions of others locked up for whom she/he serves as representative.

“I’ve watched a lot of prison films, documentaries and non-doc’s, and they kind of all take the same shape,” Story told Guernica recently. “You go inside a prison, you point the camera at a black man in a cell and the narrative, especially if it is a progressive or liberal film, will expose what’s going on. You expose the violence, you expose the injustice of this person’s incarceration, or you tell a redemption story, or transformation or an innocence story. It seemed to me that these narratives have their place, but there are limitations to them.”

In her deliberate refusal of orthodoxy, Story comes up with a structure that leaps across geographies, communities and themes: an unnamed female prisoner talks about fighting fire in Marin County with the California Department of Corrections (she is proud of the work but knows she won’t be a fire-fighter after release because of her conviction); a resident of a post-coal Kentucky town thankful for “recession proof” prison jobs; poor Missouri residents kept down by over-policing and rampant ticketing; an overly eager spokesperson for Quicken Loans who has drunk the corporate-Koolaid and extols the virtues of wholesale regeneration, rising rents and private security firms in downtown Detroit; an entrepreneur who negotiates the byzantine NYDOC mailroom rules so prisoners’ loved ones don’t have to.

The twelve vignettes are tied together by a looming music score and studies of smoke, steam and clouds. We’re all under the same sky, we all breathe the same air. Huge credit to Director of Photography Maya Bankovic and Editor Avrïl Jacobson too.

This film manifests the visuals for abolition activism. Prisons are all around us. They emerge from capitalist logic and conform to economic and geographic structures that are both produced by, and the producer of, racism, classicism, social immobility and chauvinism. Prisons are not about solving crime; they are a punishment of people outside white hetero-normativity. Prisons brutalise marginalized communities by further excluding them from opportunity and thereby delegitimizing them; prisons allow for existent power to confirm its prejudices and further its abuses.

Again from Story’s interview with Guernica (which I can’t recommend highly enough) she explains how a narrative knitted through seemingly disparate, seemingly ordinary places reflects the pervasiveness of the problem and also the near invisibility of its (most obvious) infrastructure, the prison building itself.

“I was very cognizant of how difficult it is at this moment to get inside prisons. There are more prisons than ever before, but they are further away and more locked down than ever before. So, I was really interested in the psychic distance created by that geographic distance, and the way in which prisons are spaces of disappearance but also spaces of massive infrastructures, as buildings that hold lots of people, but they’re also disappeared in the landscape.”

Furthermore, on the limits of criminal justice reform conversations, and how those conversations cannot be separate from critiques of economic inequality and labour rights, Story says:

“So long as we are confined to thinking about [prison reform talk] just as a problem of imprisoning the wrong people or punishing people too much, then we don’t actually get at the fundamental relationships that have created the prison build up in the first place. In terms of people on the right and the neoliberal democrats as well, who are all about championing prison reform like the Koch brothers, well they are the biggest union busters in this country.”

“We can’t think about prisons and the problem of mass incarceration outside of the problem of labor. There’s a direct correlation between the stagnation of workers, wages, structural unemployment, especially for African Americans, and union busting. This sort of neoliberalism from the 1970’s onwards maps intimately alongside the rise of the carceral state. In some ways, I want to say who cares if the Koch brothers want to say we’ve locked up too many people and we want to put some money into prison reform. But, let’s not get too excited about that because at the same time they are still undermining worker power and undermining good jobs and good wages at every turn. There’s too close of a relationship between workers and the problem of unemployment, the problem of poverty and mass incarceration in this country.”

The Prison In Twelve Landscapes has already won a raft of accolades including a nomination for Best Feature Length Documentary at the Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television. Paste had it as one of their best documentaries of 2016. In a glowing review, The New York Times said soberly, “What we see is no less than the draining of hope from one group of citizens to benefit another.” Cinema Politica had it as one of their best political documentaries of the year. It is a film that is impeccably crafted and one that credits its audience with intelligence. It treats the complex issue of mass incarceration in a complex way.

Some of the most infuriating scenes are those from Ferguson, Missouri. Story went there one year after police officer Darren Wilson murdered Michael Brown. Story met citizens like Sherie (above) who faced either a $175 fine or jail. What for? For not securing a trash-can lid. Derrick (below) talks of continual harassment, arrest and fines.

“These communities are over-policed,” explains Story, “because the revenue model is generated based primarily on police fining people of color, mostly poor people for incidental violations like traffic violations. So there is already an existing infrastructure that floods these communities with police, and this is part of the story that gave rise to this murder.”

DuVernay’s 13th, and Story’s The Prison In Twelve Landscapes are two quite different films, yet they complement one another and support the arguments of the other. (I wonder what the effect of 12 Landscapes would’ve been had it had the worldwide Netflix distribution that 13th enjoyed?)

13th walks the viewer through a literal historical narrative by means of stats, facts and talking heads. DuVernay illuminates the racist underpinnings to criminal justice and execution of law, drawing the line from slavery, to abolition, to the 13th Amendment, to convict leasing, to Jim Crow, to modern day prisons. DuVernay wants to confront us with the blatant injustice of it all; Story wants to shock us with our complicity in it all.

The two films can be understood as the feedback of one other. DuVernay shows us the injustices of the past, but Story shows us how difficult they are to untangle from the present. We’re caught in a destructive loop. Without a significant reordering of society we are destined to continue the abuse and wastage inherent to mass imprisonment.

The Prison In Twelve Landscapes is a landmark achievement in documentary making. “It’s rare that a film this outraged is also this calm,” said Village Voice. It is a film that is true and true to its form. It is creepy, troubling and near; it is a prism on our society that should deeply unsettle us. It is the best film of 2016 not to win an Oscar.

–

This is great –> Story’s Five Book Plan: Carceral Geography.

Peep my 2013 article The 20 Best American Prison Documentaries.

Story’s Guernica interview on the whys, whats and hows of her work.

Follow The Prison In Twelve Landscapes on Facebook and Twitter.

Follow Brett Story on Vimeo and Twitter.

–

* If 13th is shortlisted, I hope it wins as that could only benefit the ongoing awareness about the racist, classist and abusive functioning of prisons and sentencing. Honestly though, I don’t think 13th will win. It uses a formula template of chronological narrative. 13th is a very important film but it doesn’t experiment enough with the documentary form itself. I think Cameraperson will win.

** Update: 14:00 GMT. Cameraperson wasn’t shortlisted, so my prediction withers. Fire At Sea (Gianfranco Rosi and Donatella Palermo); I Am Not Your Negro (Raoul Peck, Rémi Grellety and Hébert Peck); Life, Animated (Roger Ross Williams and Julie Goldman); O.J.: Made In America (Ezra Edelman and Caroline Waterlow); and 13th (Ava DuVernay, Spencer Averick and Howard Barish) were shortlisted for Best Documentary Feature.

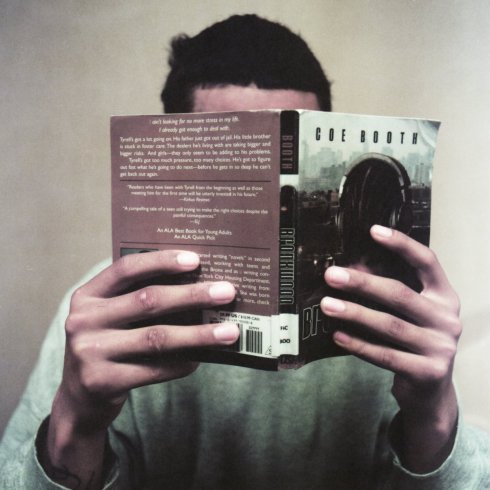

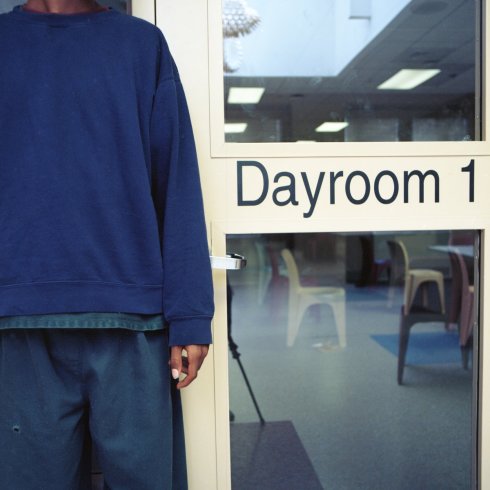

Over a period of six months, between the summer of 2014 and the winter of 2015, Amber Sowards shot 20 rolls of film in the Dane County Juvenile Detention Center in Madison, Wisconsin. The series of portraits she made is called Captured.

“The series hopes to expose the general community to what life is like for incarcerated youth in Dane County,” writes Sowards. “While at the same time creating a visual narrative that documents and puts a face to what racial disparity looks like in present day Dane County.”

The population changed over the months. Many young people left the facility during the project’s run. Others arrived. Some weeks, Sowards saw three teens. Other weeks she worked with 25.

Sowards’ directions to the youth were minimal.

“I asked if I could photograph the youth and then I picked the location of the shot,” she says. “Then we just had a conversation and photographed naturally. Most of the teens really liked having their photo taken; it made them feel valued.”

The conversations were so striking that it soon became evident that teens’ voices were central to portraying their life as those “in an unnatural environment”. The voices in aggregate challenge the audience to imagine alternatives to incarceration, something more natural.

They were collaged into a 5-minute track which you can listen to here.

“We did not intend to pair the photographs with audio [at first],” says Sowards. “That decision came later.”

As with most other portrait series of incarcerated youth, anonymity is a prerequisite. The genre of portraiture becomes a hell of a lot harder when you don’t have facial expression and eye contact to work with. The thing that strikes me about Sowards’ work (and it might just be the softer edge of analogue photography) is that the children seem to adhere to the palette of the place. The images are diffuse with the blues, beiges, grey and white light of the facility. The chess board and the green ball are sharp punctuations of color.

There’s an noticeable degree of civility in the environment too. While the interiors and hardware are unmistakably institutional there’s clearly an array of activities at the teens disposal. The viewer is left in no doubt that these prisoners are children and therefore, I hope, viewers carry with that an expectation and optimism that this is a space that will help the teens in the long term. If this seems a modest hope then consider that in many photographs of (adult) prisons a complete lack of care, protection and nurturing is most evident, and is the norm.

Sowards says some staff at the Dane County Juvenile Detention Center were fine with her presence and that of her camera. Other staff members were uncomfortable. This too suggests that the juvie depicted here might be for some therapeutic. In facilities where cameras are not welcome, where they are a considered a threat, one assumes that not all is right. Fortunately, for these teens, not the case here. Captured is a pleasant, modest look inside a previously unknown microcosm of Madison, Wisconsin.

Captured was sponsored by GSAFE and delivered through its New Narrative Project. GSAFE increases the capacity of LGBTQ+ students, educators, and families to create schools in Wisconsin where all youth thrive. The New Narrative Project aims to foster self-determination through custom-designed workshops that help incarcerated youth access their potential and think analytically about the social justice issues they are impacted by.