You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Opinion’ category.

© Kenneth Jarecke

Ken Jarecke (blogs at Mostly True) is a world-renowned photojournalist and founding member of Contact Press Images, an illustrious photo agency based in New York.

On Friday he poured his heart out at Tiffin Box:

No, I’m sad and ashamed to report that my lack of desire stemmed from nothing more than a lack of money. More specifically, the constant worry, and the ongoing struggle to pay the bills had taken its toll.

It’s sad, because I didn’t become a photojournalist to get rich (I was never that crazy or misguided). I’m ashamed because much of my money problems were the direct result of poor or stubborn decisions that are completely my fault.

He doesn’t hold back:

Pride and arrogance, a nasty couple of vices. As you can imagine, the only people to suffer from the choices I made was my family. Over the past few years, we’ve cut expenses, and eliminated most of the extras that come with family life, in my vain attempt to reinvent the editorial market and make things right (vanity, there’s another one).

Although I never stopped loving being a dad or a husband, the only thing I accomplished was to give my family a grouchy dad who hated making pictures.

Also recently, one of his daughters got serious ill, it gave him new perspective, Jarecke’s’s not proud anymore, he’s not too worried about bills, he’s taking portrait jobs, having a print sale and moving forward. He just wants more than ever to be a better dad and husband.

It seems to me that Jarecke has said what many are feeling. Bravo Kenneth for your honestly and vulnerability!

Photo: Chip Litherland

I spent all day looking at photography and this was the last thing through my RSS. Exhausted but pissed off, I have to post.

Chip Litherland (@chiplitherland) was on assignment for this story in the New York Times, and shared a few images on his blog. I simply copy & paste the comment I left with Chip here:

The red hues, the spot light (recalling war photography), the drama in general but most of all the solemnity of Jones who poses between the ultimate Hollywood myth and a shooting target – it reeks of a man who’s more obsessed with theatrics & violence than he ever will be with reality.

I expect this was one time you wanted to put down your objective journalist persona and tell him straight he’s a liar, a nutter and a danger to those fooled by his hate.

More of Chip’s images here.

Fair Warning: This will probably be the only post I do about the Islamophobia gripping the vocal minority in America. There’s no point talking about it; it’s hate and those spewing it are dangerous simpletons. My only worry is that TV will continue to bombard people with heady graphics, drastic statement and “passive wonderment” (as Jon Stewart has best described it). At this point, Fox News conjures the wildest conspiracy theories in America.

“Women actively participated in every significant photographic movement and school of the twentieth century. […] As a young historian I discovered that a little digging in any period yielded important women who had been exhibited and published locally, nationally, and internationally. Women’s representation and the acknowledgment of their contributions declined or disappeared only when later historians evaluated a movement. The more general the compendium, the less likely women were to be well represented.”

Anne Tucker’s foreword for Reframings: New American Feminist Photographies

Kate Wilhelm of Peripheral Vision has put together a thoughtful post about the exposure, visibility and success of female photographers in the industry. Wilhelm’s main contention is the standards that exist in photography are male standards, a set-up particular to photography and not seen, as such, in other visual arts. I think she might be on to something.

I think photography (particularly fine art) is aggressively contested and often antiseptic, emotionally detached photos win over. I am not saying women have the market on emotion, but I do think female photographers might be attracted to subjects other than the cold observations that tend to dominate.

We seem to welcome softness, expression and emotive content in painting, but we either balk or yawn at the “sentimental” use of bokeh, lens flare, and golden hour dreamscapery in photography. I guess I worry that photography can be a cynical practice (?)

Photography has become synonymous with detachment and I think men are more comfortable celebrating detachment … Je suis désolé … I argue that solitary aesthetics, pursued by men in photography, have influenced the judging standards across the entire discipline.

Wilhelm provides these stats, which are her own observations, counts but a good start for discussion.

500 Photographers has only covered 17 women out of the 94 photographers it’s so far covered. That’s 18 percent.

Image Makers Image Takers has interviews with 20 photographers. Five of them are women. (Incidentally, it was edited by a woman.) That’s 25 percent.

The photograph as contemporary art, by Charlotte Cotton, discusses 219 photographers, give or take a few. 91 of them are women. That’s 42 percent.

I was sorry to hear that, after 6-and-a-half years, Big RED & Shiny has decided to close up shop. It’s 135th issue will be its last. It’s not ending operations due to money but because its just arrived at that time.

BR&S’s self-defined scope was the New England Arts scene, but in reality its reach and applied knowledge was national.

In my past writing I have leant on some of the great photography articles at BR&S – Larry Sultan, William Christenberry, Harold Feinstein and Stephen Tourlentes.

BR&S has had over 170 contributors down the years and the sites development stands out as a true community; the writing has been considered and committed – Matthew Gamber was editor-in-chief for 126 issues; writers turned editors, Micah Malone and Christian Holland, started with the first issue; James Nadeau first wrote an article in issue #19 and remained as editor.

Matthew Nash, publisher of BR&S said this:

If Big RED & Shiny were a human, our six-and-a-half years would put them in the first grade. Yet, online we are old. Very old. We have been online a full third of the life of the Internet. There was no Facebook when we started. No Blogger. No MySpace. The iPhone was over 3 years in the future.

If Nash is suggesting that BR&S has less of a place in the rapidly changing internet (which I’d currently characterise as an idea-economy, link-economy, micro-blogging, shuffling-content internet) then he is surely wrong. He observes that perhaps people have less need for editorial framing and more an appetite for primary content. Nash could be right, but I don’t know if that means editorial writing is pushed out. I hope that there’s room for both – I mean, a tweet (which is essential a quick-fire bulletin board) does not compete with a full length article (which is substantive content, ideas).

Whatever. The debate on the web is a distraction really from an announcement that means our arts coverage online just got a little thinner. Thankfully, the archive lives!

BR&S – Sad to see you go. Good luck with future endeavours!

It’s pretty cool that if you punch in ‘Broomberg and Chanarin‘ on Google, after their website, my commentary is next up.

I have great respect for Broomberg and Chanarin’s work.

Don’t worry, it won’t go on my resume or anything but it shows at least Google notices what I’m doing.

What would be the phrase for this faceless recognition? Googlelove > G-Love > Glove? I’m wittering.

Image: From Afterlife, an investigation and de-construction of iconic images taken in 1979 that came to define a moment in both Iranian and photographic history. (Source)

Large hangars and fuel storage, Tonopah Test Range, Nevada, distance 18 miles, 10:44 am. © Trevor Paglen

I’ve tried talking about Trevor Paglen’s expansive oeuvre before, with particular reference to his documenting of Black Sites (US extrajudicial prisons). I don’t think I did a great job, which is why I am happy to see Joerg and Asim both grapple with Paglen’s contributions.

Conscientious interviews Paglen

‘What I want out of art is “things that help us see who we are now” – and I mean this quite literally. I think of my visual work an exploration of political epistemology (i.e. the politics of how we know what we think we know?) filled with all the contradictions, dead ends, moments of revelation, and confusion that characterize our collective ability to comprehend the world around us in general.’

Asim Rafiqui delves deep: ‘Photographing The Unseen Or What Conventional Photojournalism Is Not Telling Us About Ourselves.‘

‘[Paglen’s photographs] remind us how most photojournalists prefer to pander in the simple, the obvious and the conventional, while never engaging in the complex and crucual. Our newspapers and photographers have, either out of convenience, laziness or sheer careerism, chosen to veil the GWAT behind beautifully rendered and largely distracting projects produced from the confines of embedded positions on the front line.’

Of course, war photography is only one aspect area of photojournalism, but the argument can be made that criticism of war photography has stopped short, cowered or just missed the point. If one accepts that as the case, then Jim Johnson‘s three posts about the changing conventions in war photography (here, here and here) are a good lesson in how to think and see war photography, which let’s admit it, is a genre America still dresses in wonder and heroic myth.

There’s been a few parallels drawn between cameras and guns recently.

Gizmodo reflected upon new laws that would suggest that to wield a camera is to act as a dissident and warrant attention from the police. Carlos Miller continues to collate “interactions” between photographers and law or security enforcement.

Fred Ritchin picked up on this drawing parallel between the Wikileaks video of the Iraq helicopter assault and the photographing of on duty police officers, “the former is certainly prohibited by law, and the latter is now also prohibited by law in some states. Both issues relate to the conduct of military/police forces and the inability of people to publish imagery that may point to excesses.”

Susan Sontag usually crops up when one discusses the violence of photography. Whether or not Sontag was the first to coin this notion I don’t know. I do know her writing about quite complex things can be beautiful, clear and accessible so perhaps she deserves recognition for simplifying and readying the idea that photography can be/is aggressive.

On the other hand, David Goldblatt – as Fred Ritchin argues – was a dispassionate practitioner who shied away from such comparisons.

Goldblatt, “I said that the camera was not a machine-gun and that photographers shouldn’t confuse their response to the politics of the country with their role as photographers.”

Goldblatt was not a dispassionate man, but a photographer who maintained a distance, developed his own language and avoided many of the frightful images that, for example, the Bang Bang Club produced for the world’s media.

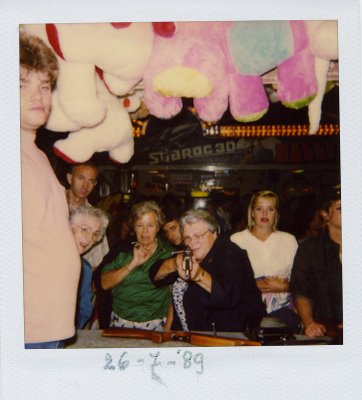

Shoot! Rencontres d’Arles

In light of these recent commentaries, this exhibition review in The Guardian (originally in Le Monde) caught my attention:

In Shoot! Clément Chéroux, a curator at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, returns to a once popular fairground attraction. When it first appeared in the 1920s, target-shooting enthusiasts could take home as a prize a photo of themselves in action. When the bullet hit the bull’s-eye, a portrait was taken automatically. By the 1970s the attraction had disappeared, but there is no nostalgia here. “I’m not paying tribute to a vanished process,” says Chéroux. “What interests me is its metaphorical side. […] Of the 60 or so exhibitions at this year’s Rencontres d’Arles the most successful and original is certainly the one on the photographic shooting gallery.“

With work from Patrick Zachmann, Christian Marclay, Martin Becka, Rudolf Steiner and Erik Kessels the exhibition is a varied interpretation of camera and gun, or in the majority of these cases, camera and rifle. Looks like a unique and winsome show. More here and here.