OPENING REMARKS

I’ve stated it before but not often or forcefully enough: The LGBTQ community nurtures many of the most effective and motivating voices in the fight for prison abolition. LGBTQ people are frequently subject to the harshest and most dehumanizing treatment at the hands of the prison system. It is from this position that activists and formerly incarcerated individuals have mobilized against the prison industrial complex.

In the news, it is the circumstances of transgender people in prison that are most often described and decried. For clear reasons: imagine being held within a male facility when you identify as female. Or in a female facility when you identify as male. Read up on the situations of Marius Mason and Vanessa Gibson. In Pittsburgh, Jules Williams, a transgender woman suffered sexual and physical assault and harassment multiple times while detained at the Allegheny County Jail, a mens facility.

Very, very few prison or jail systems place transgender folx in facilities where they are free of victimization and predation. During her three years of incarceration in the Georgia Department of Corrections, Ashley Diamond was repeatedly assaulted, once after GDC officials placed her in a cell with a known sex offender. Diamond took the radical step to appeal directly to the public via “illegal” YouTube videos from her prison cell made on a contraband smartphone.

Diamond won freedom following a lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the conclusion was that the GDC didn’t want to deal with the expense and supposed inconvenience of providing the hormone treatments she’d been on for 17 years prior to her imprisonment. Similarly, in California, Michelle-Lael Norsworthy was freed unexpectedly when her lawsuit for access to healthcare threatened the CDCR with huge medical bills. Shiloh Quine won the right for sexual reassignment surgery, but hers, all too unfortunately, was an exceptional case.

(For an instructive overview of the experience of female trans prisoners, read Kristin Schreier Lyseggen’s book Women of San Quentin: Soul Murder of Transgender Women in Male Prisons which details the stories of nine women, including Janetta Johnson, Tanesh Watson-Nutall, Daniella Tavake, Diamond, Quine and others.)

While transgender people are winning more and more hard-fought recognition in open society, prisons occupy the other end of the spectrum—closed, rigid systems unable to safely house the majority of prisoners and certainly unprepared and, more often, patently unwilling to recognize prisoners with gender dysphoria and their specific needs. (Trans issues are at the forefront in the military again. The regressive and punitive White House is banning transgender personnel from service. Unsurprisingly, DJ Pee-Tape is largely at odds with much of the military command.) Historically, the marginalization and criminalisation of LGBTQ people has funneled them into the criminal justice system, too. That point needs to be made.

Transgender prisoners are just one group within the LGBTQ community. Lesbians and gays face daily vilification within the criminal justice system. The tactics for resistance of different groups within the LGBTQ community necessarily vary in specific ways, but the enemy is common.

In a push back against the homophobia and transphobia embedded within the criminal justice system we should look to leaders such as CeCe McDonald, Dean Spade and Reina Gossett. Their intersectional critique of policing and prisons connects the dots between discriminations of all types. Prejudice and inequality exist within our society; certain groups, including LGBTQ and particularly LGBTQ persons of color, are valued less than others. The root causes for racism, sexism, imperialism, militarism are the same, and those root causes not only emerge out of capitalism but are, in many ways, its foundations. The complete abandonment of LGBTQ persons’ needs in prisons brings into sharp focus the fact that the systems, and our society from which they grow, deem this group more disposable than others.

“Prison abolition means no one is disposable,” says Reina Gossett. Exile is not a solution to the shortcomings of a society; exile allows wider discrimination to perpetuate.

“We should not model what the state’s logic is about who is disposable,” Gossett continues. “Challenging and dismantling structures of violence. [We need] relationships modeled on a different logic, not on the logic of white, heteronormative hegemony.”

Seen through a queer lens, the violence of the prison industrial complex is laid bare. Prisons are sites of waste and sites of survival; sites into which those outside the dominant norm are discarded. True to capitalist, carceral logic, the only economic benefits prisons bring about are for the state, law enforcement unions, corporations and craven politicians. We, the taxpayers, hand over this wealth at the expense of the lives and livelihoods of all those locked up. In the modern U.S., prisons are not about “time out” or rehabilitation; they’re about control in order to instill order. Prisons crush humanity and they assault diversity.

Prison abolition is about identifying structures of violence and working against them; about prefiguring a better world in which you want to live. In reviewing the book Queer (In)Justice (Ed. Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock), journalist and activist Vikki Law notes the authors’ contention that “deep-seated prejudices and fears of queer people cannot be dismantled via hate crime legislation.” Social attitudes are the strongest underpinning to a just society, not the latter-stage adjudications of the law.

“The authors say,” continues Law, “that ‘many of the individuals who engage in such violence are encouraged to do so by mainstream society through promotion of laws, practices, generally accepted prejudices, and religious views,’ and they note that homophobic and transphobic violence generally increases during highly visible, right-wing political attacks.

(For an introduction to community organising toward abolition, read James Kilgore’s recent piece Let’s Imagine a National Organizing Effort to Challenge Mass Incarceration.)

Prison abolition is about pushing back on all the structures that manifest the suspicion, dismissal and abuse of people who counter the white patriarchal status quo. That includes visual structures. That includes, as Critical Resistance states, “the creation of mass media images that keep alive stereotypes of people of color, poor people, queer people, immigrants, youth, and other oppressed communities as criminal, delinquent, or deviant.”

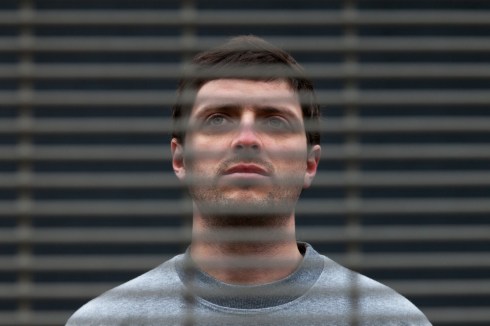

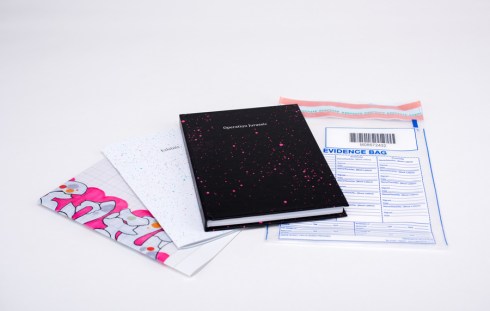

That is why Lorenzo Triburgo’s project Policing Gender is so important. Triburgo, a trans man, is not only advocates for the larger LGBTQ rights at stake, but also makes images that bring the weight of photographic history and analysis of images’ power to bear on his decision-making and design. His is a queer perspective. Policing Gender is enigmatic and beautiful and devastating. Triburgo’s personless portraits point us past what the images are in-and-of-themselves and toward a critique of what images have done in the past in service of, and to damage, LGBTQ-identified people.

I can make no apology for the length of these introductory remarks, because these photographs are built upon years of Triburgo’s conscientious thought, and on decades of queer activism by countless others. Context is important. From here, I’ll let Triburgo himself explain the conceptual underpinnings of Policing Gender and just add how grateful I am for our extended conversation. Scroll down for our Q&A.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): We first met in Portland around 2012 or 13. We published a conversation in 2014. At that time you’d just picked up research for a photographic project on the topic of mass incarceration. You explained then that you’d wanted to do portraits of families, but the warden explained that the visiting room had a program for such portraits. The idea was shelved for a while, as you made Transportraits, but you knew you’d come back to it. Family portraits are very different to these curtains and aerial landscapes. How did you get from there to here?

Lorenzo Triburgo (LT): When I began Policing Gender I collaborated with the queer prison abolition organizations Black & Pink and Beyond These Walls to become pen pals with over 30 LGBTQ-identified prisoners. I wrote and talked with my pen pals for months and months before deciding on what the project would entail visually.

Keep in mind that I also worked to gain access to various prisons and jails. I was doing my *photographer’s due diligence*. However, after getting inside, I thought, “F##k that. I’m not going to create photographs that could potentially strengthen the association between queer people and criminality.”

I kept obsessively thinking, “I want to make portraits, but not portraits. Portraits, but not portraits.” I was wracking my brain. The reasons were twofold.

First – ethically, as a queer person, feminist, and artist I am particularly sensitive to issues of representation and exploitation. I could have made the portraits but, to what end? How radical can a straightforward portrait really be? Would portraits of queer prisoners bring anything to the world besides an opportunity for viewers to gawp or sate their curiosity and voyeurism?

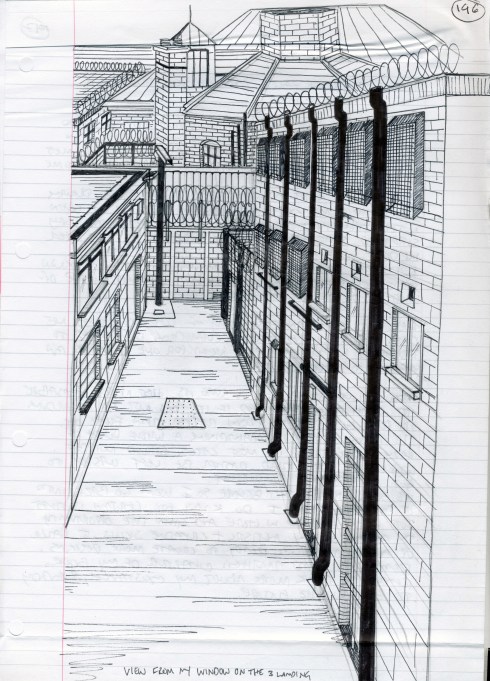

One of the hellish qualities of prison is the complete lack of privacy. Random administrators, politicians, teachers and students might make visits to a prison and get led on “tours” where they can peer-in on any prisoner through a tiny window and just watch. Did I want to replicate that experience with my camera lens? No.

Furthermore, how would I know for sure that I was getting informed consent from participants? In what world would our exchange be equal? Even more importantly, in what world would the exchange between any prisoner and viewer be equal?!

Secondly, conceptually, I felt my project demanded a complex approach that would embody the depth, pervasiveness, scale and abuses of the U.S. prison system. It needed to be more than a single-layered visual representation; more than a straightforward portrait.

LT: I started to think about making portraits with no figures.

What if instead of putting my incarcerated pen-pals on display, I go a quieter more contemplative route and conjure a sense of absence? The next step was to figure out what the figureless portraits would look like. I recalled a lecture by Cathy Opie where she cited renaissance portraitist Hans Holbein as a major influence. Holbein and Opie use fabric as a symbol of wealth, power and beauty.

PP: But to different ends.

LT: Yes. Opie appropriates formal aesthetics in order to queer the photographic portrait. I saw that I could use fabric and create connotations of portraiture and, for some of us, make a nod to queering the portrait through the use of form. It felt I’d found an answer to the inevitable imbalance of power between prisoner and viewer that I wanted to avoid perpetuating. Figureless portraits point toward this thorny ethical ground.

While thinking all this through, I was discussing my ideas with activists and researchers including Dr. Susan Starr Sered, co-author of Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility. Dr. Sered and I had a conversation that solidified my decisions.

PP: On your work’s figurelessness, an editor with whom I spoke recently referred to your work as “withdrawn”. It wasn’t a criticism per se, but I wonder about your reaction to that assessment?

LT: My pen-pals are trans and queer, and young and old, and out and not out, and coming out for the first time, and helping others come out for the first time all behind bars. I wrote and talked with them for months and months before deciding on what the project would entail visually. The decision to exclude people in the images is not ONLY about theoretical distancing from prisons and a challenge to photographic voyeurism. It’s also about anonymity for safety reasons and my pen-pals not always being able to come out without endangering their safety, and about recognizing that prisoners are a protected subgroup and not always able to give knowledgeable consent.

The figurelessness is about the absence of 2.3 million prisoners from society.

It’s difficult to communicate absence through photography but that was a risk I wanted to take. I believe we are at a stage when absence can be just as powerful as presence because there is so much photographic presence.

The work isn’t withdrawn. It’s emotional. It’s meditative. It’s quiet. I’m asking the viewer to take a minute and reflect: on their position in the world, on their assumption that they get to “see” whatever they want to see, and on the people who are missing from our society.

The lighting in these pieces was a meditative process for me. It was a way for me to process what I was learning about from my pen-pals. It’s not a vapid conceptual piece in reaction to the prison system. Each fabric represents a set of circumstances that was told to me by my pen-pals and is therefore named after them — each is a combination of their names.

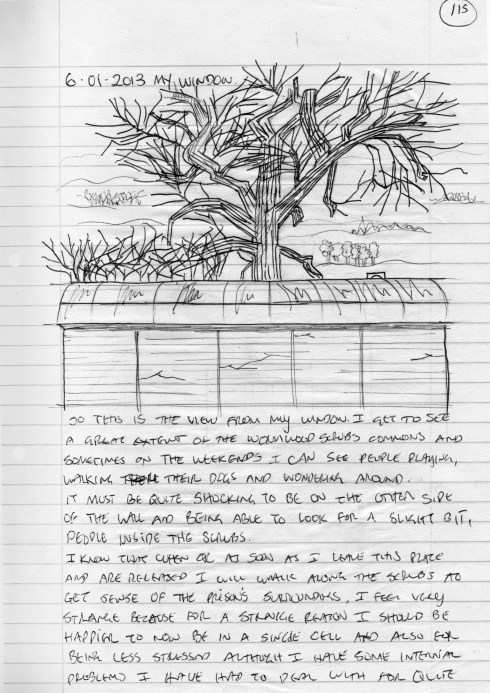

PP: And what about the aerial shots?

The aerial images are about surveillance. The construct of imprisonment. The natural contained. Creating these was also an emotional process. I was in the hot air balloon …

PP: Wait! You were in a hot air balloon?!

LT: Ha! Yes. I photographed from a hot air balloon.

Balloons were an early method used by photography in the service of surveillance. During the U.S. Civil War, hot air balloons were used to create the first aerial reconnaissance images. I was looking for a way to undermine the idea of surveillance and to portray a grandiose notion of the ‘natural’. But once I was up there I couldn’t escape the feeling of my social position, the feeling of sadness and anger and unearned privilege and wishing that I could bring my pen-pals up in the air with me. The aerial photographs ultimately reflect these emotions and, metaphorically, the inescapable presence of surveillance.

All of my emotional experiences have a direct correlation to my conceptual interests in photography. It’s how I process the world.

I think about portraiture all the time. I feel the experiences of my various identities and ways I present myself to the world and the way I’m “seen”. I see oppression based on identities and I process that by creating photographs, and in the case of Policing Gender, audio art, too.

Photography is a way for me to make sense of the world and for me to present ideas to the world. These ideas are emotional as much as they are political and theoretical because I feel like I live them. I’ve had someone else’s camera pointed at me because I seemed “interesting” and it feels like crud.

PP: How are LGBTQ identified people affected by the prison industrial complex?

LT: Right now there are 1.6 million youth facing houselessness in the U.S. We know that 46% of these youth are LGBTQ identified. Add to that, cities across the U.S. are increasingly passing laws that ostensibly make it illegal to be homeless. Over the last ten years, there’s been a steady increase in the number of cities that have made it is illegal to lay down, sleep, or even sit in public and (in cities like Houston) to share or give food to people. Once queer youth are arrested and detained they are more likely to be sentenced to jail time and serve longer sentences than their non-LGBTQ peers.

We also know that people who have been arrested have a higher chance of returning to jail or prison. So, these youth grow up to be LGBTQ identified adults with a much higher chance of spending time in U.S. prisons. This is especially true for people of color, youth, immigrants, differently abled, and poor people. So, are queer people in prison because they are queer? If we look at the systemic level, rather than a matter of individual choices, the answer is yes.

PP: Which LGBTQ-focused individuals and organisations are working specifically and effectively against mass incarceration?

LT: The book Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex edited by Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith is an invaluable resource for just this question. It was published by AK Press soon after I began Policing Gender; this book came to me at exactly the right moment and is an invaluable resource.

Captive Genders includes first person narratives, research, and political analysis with an emphasis on writing from current and former prisoners.

I personally worked most with Black & Pink and Beyond These Walls.

Black & Pink is a grassroots organization that has been working in support of LGBTQ prisoners and towards prison abolition with nationwide chapters for over ten years. Their website is also an incredible resource. Beyond These Walls is Portland-based and is another grassroots prison abolition effort with a focus on supporting queer prisoners.

In the intro of Captive Genders, Stanley writes, “It is also important to highlight that women, trans, and queer people (specifically of color) have done much, if not most, of the anti-PIC organizing in the United States.”

Case in point: Miss Major Griffin-Gracy has been an activist for over 40 years and was the first Staff Organizer at The Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP). TGIJP is based in California and began as a legal project with leadership by formerly incarcerated trans women of color. Miss Major is recently retired from TGIJP but continues to be a badass inspiration to us all. (I recently saw her on the panel for the release of the book Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility at the New Museum).

The Sylvia Rivera Law Project, formed by civil rights activist and attorney Dean Spade in 2002, must also be mentioned here. SRLP provides legal aid to low-income trans, gender non-conforming, and intersex people and “is a collective organization founded on understanding that gender self-determination is inextricably intertwined with racial, social, and economic justice.”

PP: You once expressed an interest in photographing prison guards/correctional officers. Do you still?

LT: No, but I think someone should. The abuse that prisoners face at the hands of correctional officers is abhorrent — and — it is crucial to recognize that the job of correctional officer is basically designed to produce and enable a monstrous abuse of power. If we are to understand the prison industrial complex for what it is – an entire system of oppression upheld in part by the narrative that people of color, poor people, and queer people are dangerous – we also need to recognize systemic/social/economic conditions that lead someone to become an officer and the mental trauma associated with this job.

According to one study (Stack, S.J. & Tsoudis, O. Archives of Suicide Research, 1997) the risk of suicide for correctional officers is 39% higher than their peers in other professions and other studies show increased PTSD, divorce, and substance abuse. (See: Denhof, Michael D., Ph.D and Caterina G. Spinaris, Ph.D., Desert Waters Correctional Outreach, 2013.)

The effects of unchecked power, a career culture that encourages and rewards racism, homophobia, sexism, and xenophobia and corruption that goes all the way up the chain are traumatic. Hello Stanford Prison Experiment!?!

To go out on a limb, and to quote Michelle Alexander , I think of the job of the correctional officer as one manifestation of the many “efforts by the wealthy elite to use race as a wedge. To pit poor whites against poor people of color for the benefit of the ruling elite.”

Alexander continues, “Many people don’t realize that even slavery as an institution—the emergence of an all-Black system of slavery—was to a large extent the result of plantation owners deliberately trying to pit poor whites against poor Blacks. They created an all-Black system of slavery that didn’t benefit whites by much, but at least whites were persuaded that they weren’t slaves and thus were inherently superior to Black folks.” (‘The Struggle for Racial Justice Has a Long Way To Go’, The International Socialist Review, Issue #84, 2012.)

Keep in mind that people who take these jobs are predominantly working class, often with no other viable option for work because other industries have been (systematically) replaced by the prison industry in towns across the U.S. I feel myself holding my breath and my heart racing in anger as I say this.

PP: You have said repeatedly and in public that you’ll respond to any LGBTQ prisoner who writes to you. Kudos to you. That’s a serious commitment. It must also be quite the emotional experience—good and bad. Tell us about letter writing.

LT: So much here. I don’t know where to start exactly. In previous interviews I ducked the question out of fear of sounding schmaltzy, because it is super emotional and I don’t want to come off sounding all “we are the world” or like, neoliberal humanist or something.

That said, it has been fucking incredible.

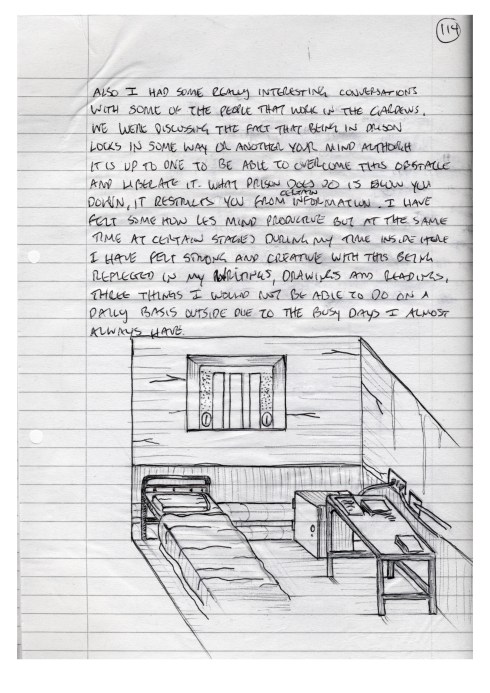

There’s something astonishing about getting to know someone slowly, over time, through written word. How often do we have the opportunity to get to know someone completely from scratch? With no photo to go by, no list of basic likes or dislikes, not knowing their preferred name or gender, or where they are from. I got to know my pen-pals’ handwriting and that is a specific intimacy unlike any other type of exchange.

I never ask my pen-pals why they are in prison. Instead, I ask about what they think are the most pressing needs of LGBTQ prisoners and what they think an artist can do. Very often the response is that a way to share their stories and their truth would be a huge help. In the audio for Policing Gender you hear one of my pen pals say, “At least out there you’ve got cell phones to record this stuff [abuse by officers], in here it’s complete secrecy.”

I’m not interested in “giving voice”—my pen-pals all have voices! But I am interested in giving their voices a platform outside prison.

By not asking about why they were in prison I aim to, at minimum, create a space for my pen-pals to talk to someone who didn’t see them first as a criminal and second as a person. I challenged myself, to be honest, to allow myself to be vulnerable, to share my thoughts, and to allow our conversations to develop without pre-judgements.

We talked about the prison system of course, but we also shared our coming out stories, what it was like during high school, whether our family was religious, our siblings, our parents, their kids. Some of my pen-pals were younger than me and grew up in the “Glee era” while others were baby boomers and couldn’t imagine being accepted as queer when they were younger. One of my pen-pals was really into Shakespeare. I am not. And we would joke about that.

I love getting to know people and their stories—so it was just wonderful in that regard. I would also simply Google information and send it upon request. It is so easy to take our access to information for granted! I would send variations on photo assignments I give my college students, making them into creative writing or drawing prompts.

There was one person with whom I lost contact and that was devastating. The last I heard of her she had been raped, then left in solitary confinement for 24 hours, then finally taken to a hospital —four hours away—given antibiotics on an empty stomach, then driven back to the prison while handcuffed in the back of a van. If you’ve ever taken antibiotics you know that they are nauseating in the best of circumstances. I don’t like to talk about stories like this too much. They are important but I also don’t want to sensationalize my pen-pals’ suffering.

I wrote with over 30 people on a monthly basis for almost two years. I still write with a small number of people and I continue to pair every incarcerated pen-pal who gets in touch with me with someone to write with on the outside. So far I’ve connected about 40 people with new pen-pals.

PP: I know you’ve designed a course on gender and photo at SVA, so if it’s not revealing any too much info, can you give us a few important titles and articles from the course reading list?

LT: My course at SVA is a studio/portfolio course where we incorporate queer studies concepts in the development and critique of projects. (The class is offered online through SVA Continuing Education. Therefore, anyone interested in exploring these ideas in their artworks can register). I also developed a graduate level seminar that I teach online for Oregon State University with a focus on representations of gender and sexuality from a feminist perspective.

Here’s a greatest hits list of texts:

- Barthes, Roland. “Rhetoric of the Image.” Image, Music, Text. Ed. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 32-51.

- Blessing, Jennifer. “Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography.” Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1997. 7-38, 67-119.

- Halberstam, Jack. “Technotopias: Representing Transgender Bodies in Contemporary Art.” In a Queer Time and Place. New York and London: New York University Press, 2005. 97-124.

- Jhally, Sut. “Image-Based Culture: Advertising and Popular Culture.” Gender, Race and Class in Media: A Critical Reader. 3rd ed. Eds. Gail Dines, Jean M. (McMahon) Humez. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2011. 199-204.

- Lorber, Judith. “Night to His Day: The Social Construction of Gender.” Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994. 13-36.

- Mercer, Kobena. “Reading racial fetishism: the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe.” Visual Culture: The Reader. Ed. Jessica Evans, Stuart Hall. London: Sage Publications, 1999. 435-447.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Visual and Other Pleasures (Language, Discourse, Society). 2nd ed. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 14-30.

- Rosler, Martha. “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography.)” The Photography Reader. Ed. Liz Wells. London: Routledge, 2003. 261-274.

- Sullivan, Nikki. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. New York: NYU Press, 2003.

- West, Candace, and Don H Zimmerman. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society Vol. 1, No. 2. (1987): 125-151.

LT: I also want to give a shout out to these texts that strongly shaped my aesthetic and ethical decisions in Policing Gender:

- The Subversive Imagination: Artists, Society, and Responsibility, Carol Becker.

- Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 2011. Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

- Queer (In) Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States, Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock.

- Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith.

- Are Prisons Obsolete, Angela Davis.

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander.

- Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility, Susan Starr Sered and Maureen Norton-Hawk.

- Punishment and Social Structure, Georg Rusche and Otto Kirchheimer.

PP: Wow, thank you, so generous. So many new texts for me. Have you a resource list of organizations working in solidarity with LGBTQ prisoners?

LT: Absolutely, these are organizations as listed in the book Captive Genders:

All Of Us Or None

1540 Market Street Suite 490, San Francisco, CA 94102

415.255.7036 [ext 308, 315, 311, 312]

info@allofusornone.org

http://www.allofusornone.org

ACT UP Philadelphia

P.O. Box 22439, Land Title Station, Philadelphia, PA 19110-2439

actupp@critpath.org

http://www.actupphilly.org

Audre Lorde Project

85 South Oxford St., Brooklyn, NY 11217

718.596.0342

http://www.alp.org

Bent Bars Project

P.O. Box 66754, London, WC1A 9BF, United Kingdom

bent.bars.project@gmail.com

http://www.bentbarsproject.org/

Black and Pink<

c/o Community Church of Boston, 545 Boylston St., Boston, MA 02116

http://www.blackandpink.org

BreakOUT!<

1600 Oretha C. Haley Blvd., New Orleans, LA 70113

http://www.jpla.org

Critical Resistance

1904 Franklin St, Suite 504, Oakland, CA 94612

510.444.0484

http://www.criticalresistance.org

FIERCE!

437 W. 16th St, Lower Level, New York, NY 10001

646.336.6789

http://www.fiercenyc.org

generationFIVE

P.O. Box 1715, Oakland, CA 94604

510.251.8552

http://www.generationfive.org

Gay Shame

San Francisco, CA

gayshamesf@yahoo.com

http://www.gayshamesf.org

Hearts On A Wire

(for folks incarcerated in PA)

PO Box 36831, Philadelphia, PA 19107

heartsonawire@gmail.com

INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence

P.O. Box 226, Redmond, WA 98073

484.932.3166

http://www.incite-national.org

Justice Now

1322 Webster Street, Suite 210, Oakland, CA 94612

510.839.7654

http://www.jnow.org

LAGAI—Queer Insurrection

lagai_qi@yahoo.com

http://www.lagai.org

Prison Activist Resource Center

PO Box 70447, Oakland, CA 94612

510.893.4648

http://www.prisonactivist.org

Prisoner Correspondence Project

http://www.prisonercorrespondenceproject.com

Prisoner’s Justice Action Committee

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

pjac_committee@yahoo.com

http://www.pjac.org

Sylvia Rivera Law Project

322 8th Ave, 3rd Floor, New York, NY 10001

212.337.8550

http://www.srlp.org

Tranzmission Prison Project

P.O. 1874, Asheville, NC 28802

tranzmissionprisonproject@gmail.com

Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project

342 9th St., Suite 202B, San Francisco, CA 94103

415.252.1444

http://www.tgijp.org

Write to Win Collective

2040 N. Milwaukee Ave., Chicago, IL 60647

writetowincollective@gmail.com

http://www.writetowin.wordpress.com

PP: Brilliant. Again, thanks so much.

LT: Thank you, Pete.