You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Nigel Poor’ tag.

The Depository Of Unwanted Photographs

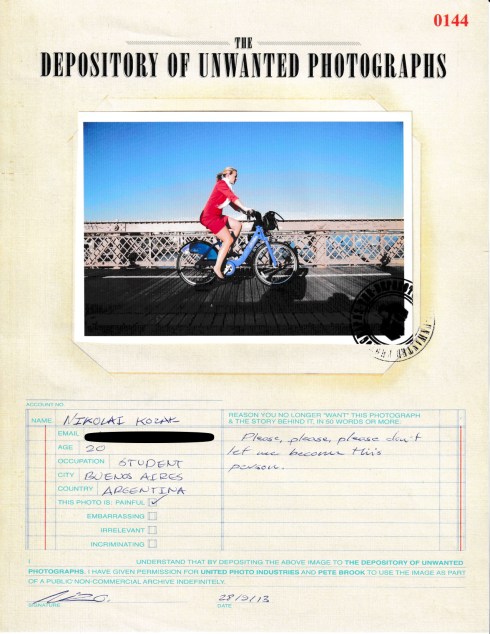

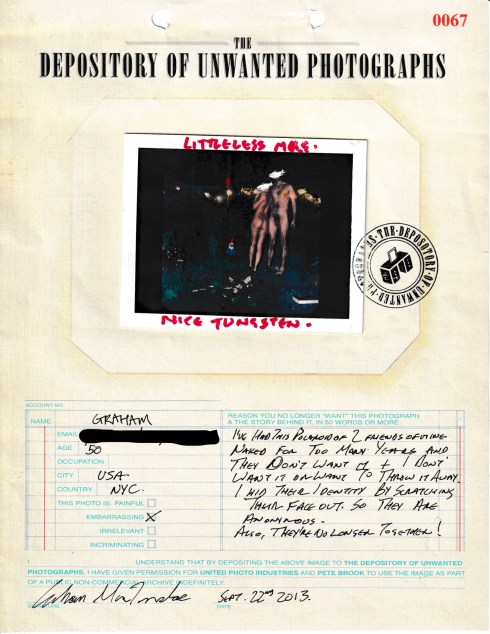

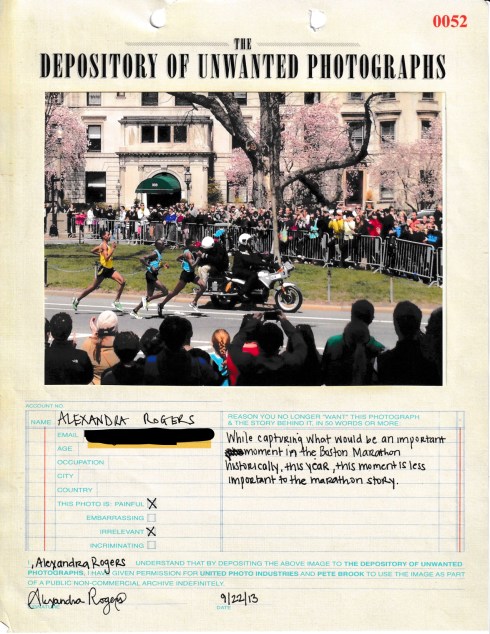

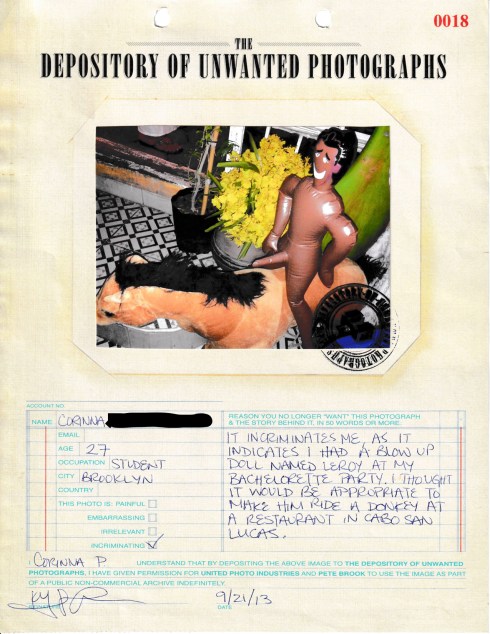

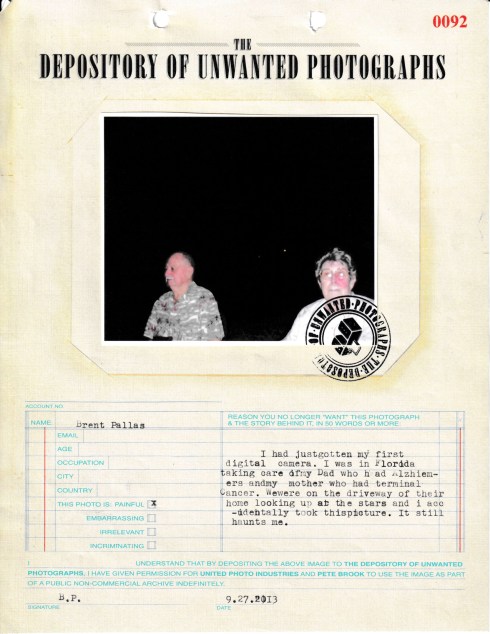

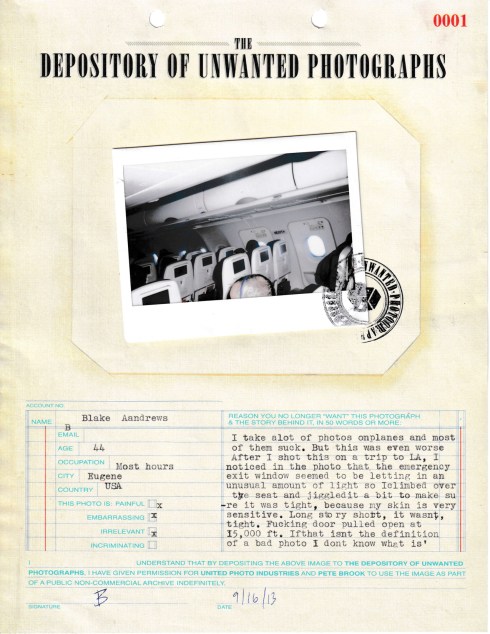

In the summer of 2013, I attempted to temporarily get out of my prison-photo-bubble and find out what people loved about photographs by asking them which of theirs they loved the least. Which did they wish to condemn to the trash-bin of history?

For two long weekends at Photoville, a couple of volunteers and I took submissions of embarrassing, forgetful, incriminating and emotionally-burdensome images. The Depository Of Unwanted Photographs (TDOUP) was born. Comprised of a little over 200 images, TDOUP has been in permanent storage over the intervening 5-and-a-half years. Well, it’s going to get a public run out.

TDOUP is part of The Past is Prologue: Vernacular Photography, Pop Photographica and the Road to Selfie Culture, showing at Art Yard in Frenchtown, NJ from April 27th-July 28th. The Past is Prologue traces the evolution of everyday photography from the late 19th century to Instagram.

The collections and works “explore a beguiling terrain comprised of unauthored and found photographs, and commercial objects and images divorced from their original contexts” including discarded works, photo booth portraiture, family albums, newspaper archive press prints, industrial catalogues, and more. From the collections of Pete Brook, W.M. Hunt, Daile Kaplan, Nigel Poor and Cynthia Rubin. Featuring the works of Marcia Lippman and Cassandra Zampini.

The opening reception is Saturday, April 27th, 6-8pm. I’ll be there.

More about ‘The Depository Of Unwanted Photographs’

When asked to name a single image they absolutely treasure, people usually don’t hesitate: a snap of their children, a family Polaroid, or a formal portrait from precious life event, for example. “What is your most beloved photo?” is a common question. “What is your worst photo?”, on the other hand, is a near-perverse inquiry.

If we’re looking for good photography, we’ll find plenty in photobooks, galleries and publications, but where do we find a legitimate and well-researched presentation of bad photography? Does our discussion of what is good not also rely on a shared knowledge of what is bad, unwanted and unloved?

TDOUP was built on a belief that vernacular photos and stories are as relevant as the stories attached to news-photo-exclusives and famous documentary images. People’s stories are central to conversation about how we consume and use photography. We create and circulate billions of images every day and we constantly employ choices (consciously and subconsciously) to share or pass over images. If we accept the mantra that “We are all photographers” then aren’t we all photo-editors too?

There might be many images any individual would want to trash, but in asking people to choose only one, TDOUP urges people to think about the value system they’ve written for their own photographs. In choosing one photo for the great big dustbin of history, TDOUP contributors can meditate on their actions as image-makers and as “editors”.

From serious concerns to exorcism of the frivolous, TDOUP distills our different experiences and priorities—a portrait of a man who’s death spurred the only time a daughter saw her father cry; an engagement ring from a union that never materialized; photos of family abusers follow those of rancid chocolate; bad pics of the moon or the street; blurry photos of friends; the last photo before alcohol-eradicated memory took hold; Polaroids with emotional burden too heavy to carry; embarrassing clichés, cringeworthy selfies; photos of an IVF clinic and of the pogo-stick world record; accidental but beautiful prints made by misfiring processors; haunting images of soon-to-die parents; and a photo from the crowd of the 2013 Boston Marathon hours before the terror attack at the finish line. The interrelation of the images is as unpredictable as the motives for their original submission.

The Depository Of Unwanted Photographs is an unpredictable interrogation of quality that crucially is made by the public, not by the dominant voices of those in the media or culture industries. Which single photograph would you state, on the record, as unwanted?

More about ‘The Past Is Prologue’

Daile Kaplan’s collection of photographic textiles represent one facet of her pioneering work in the creation of a category known as Pop Photographica, representing a range of functional, decorative and commercial objects, from coffee cans to funereal fans emblazoned with images of the deceased. The costume works from her collection in this show range from high fashion dresses to low fashion pajamas. Kaplan is Vice President of Swann Galleries in New York, and an expert appraiser of photography for the Antiques Road Show.

W.M. Hunt’s collection of press prints from late 19th century and early 20th century newspaper illustrations are drawn from his Collection Dancing Bear and Collection Blind Pirate: the former, “magical heart stopping images of people in which their eyes are obscured” and the latter, American Groups before 1950. This is the first time that Hunt, a respected and prolific collector and writer in the field, has drawn from both for an exhibition.

The artist and photographer Marcia Lippman’s installation is a meditation in found images about her life-long search for an elusive biological mother. Born in an era when adopted children were denied access to their own biographical information, Lippman’s quest has been a driving force behind her artistic practice. A short film by Elsa Mora about Lippman’s process accompanies the work. Marcia Lippman is a photographer, a teacher, a traveler, a collector, and a storyteller. Much of her work for four decades has explored the passage and residues of time along with the ephemeral nature of memory.

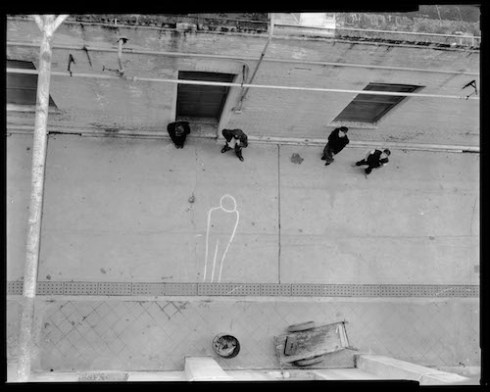

Nigel Poor is a photographer and co-founder of the San Quentin prison-based podcast Ear Hustle. In the course of her research she happened on a trove of period untitled photographs from inside San Quentin taken in the 1960s and 70s. These arresting images illuminate a world that remains hidden from view to this day.

Curator, lecturer and collector Cynthia Rubin’s collection of 19th century advertising ladies features images of women in 19th century bustles adorned with everyday objects from carpenter’s levels, bakery products and chain mail. Before the advent of sandwich boards or electronic media, women dressed in such Dr. Seussian outfits circulated the commercial districts of their towns promoting their employer’s wares.

United Photo Industries and Pete Brook created and curated The Depository of Unwanted Photographs, a crowdsourced archive of images and stories. Visitors are invited to add to the collection by donating unwanted photographs. Artist Cassandra Zampini has created a video installation representing one second of one hashtag of videos on Instagram.

Other components of the exhibition include:

A sewn timeline of vernacular images starting in the 1920s and leading to the present.

A translucent wall constructed of illuminated x-rays from the 1930s by Elsa Mora.

A Paper Moon photobooth redux. Steve Maiorano invites you to sit for a portrait while floating on a friendly moon, as was done in the 1920s and 1930s.

A rare photo album documenting a year in the life of a nine-year-old girl in 1939, palpably beloved by her family.

Hands on stereopticons and three dimensional historical photographs.

How can images tell the story of mass incarceration when the imprisoned don’t have control over their own representation? This is the question Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood asks as editor of the latest Aperture (Spring 2018).

“Prison Nation” can be ordered online today and hits the news-stands next week. Devoted to prison imagery and discussion of mass incarceration, the issue presents a slew of works across contrasting genres — landmark documentary by Bruce Jackson, Joseph Rodriguez and Keith Calhoun & Chandra McCormick; luscious and uncanny portraits by Jack Lueders-Booth, Deborah Luster and Jamel Shabazz; insider images from Nigel Poor, Lorenzo Steele, Jr. and Jesse Krimes; and contemporary works by Sable Elyse Smith, Emily Kinni, Zora Murff, Lucas Foglia and Stephen Tourlentes.

Equally exciting is the banger roster of thinkers contributing essays, intros and conversations — including Mabel O. Wilson, Shawn Michelle Smith, Christie Thompson, Jordan Kisner, Zachary Lazar, Rebecca Bengal, Brian Wallis, Jessica Lynne, Reginald Dwayne Betts, Ruby Tapia, Zarinah Shabazz, Brian Stevenson, Sarah Lewis, Hank Willis Thomas and Virginia Grise.

I have an essay ‘Prison Index’ included which looks back on almost a decade of this Prison Photography website–how it began, what it has done and what it has become. I highlight a dozen-or-so photographers’ works that are not represented by features in the issue itself. I wonder how PP functions as an archive and what role it serves for public memory and knowledge.

MATCHING QUALITY CONTENT WITH QUALITY DESIGN

I’ve known for years that Prison Photography requires a design overhaul. This past week, I’ve moved forward with plans for that. It goes without saying that the almost-daily blogging routine of 2008 with which Prison Photography began has morphed into a slower publishing schedule. There’s a plethora of great material on this website but a lot of it is buried in the blog-scroll format. My intention is to redesign PP as more of an “occasionally-updated archive” whereby the insightful interviews from years past are drawn up to the surface.

It’s time to make this *database* of research more legible and searchable. Clearly, as this Aperture issue demonstrates, the niche genre of prison photographs is vast and it demands a more user-friendly interface for this website. I’m proud to be included in “Prison Nation” but know it’s a timely prod to develop Prison Photography’s design and serve the still-crucial discussions.

Get your copy of Aperture, Issue 230 “Prison Nation” here.

Thanks to the staff at Aperture, especially Brendan Wattenberg and Michael Famighetti for ushering and editing the piece through.

WORK DETAIL

At the back-end of 2011, I paid a visit to Nigel Poor and Doug Dertinger at the Design and Photography Department at Sacramento State University where they both teach. We talked about a history of photography course that Nigel and Doug co-taught at San Quentin Prison as part of the Prison University Project. At the time, there was no other college-level photo-history course other class like this in the United States. I have no reason to believe that that has changed (although I’d happily be proved wrong — get in touch!) We cover curriculum, student engagement, logistics, and the rewards of teaching in a prison environment.

Toward the end of the conversation we move on to discuss an essay by incarcerated student Michael Nelson. It was a comparative analysis between a Misrach photo and a Sugimoto photo. The highly respected TBW Books recently released Assignment No.2 which is a reissue of Michael’s essay. Packaged in a standard folder and printed on lined yellow office paper, Assignment #2 caught the photobook world a little off guard. Reviewers that dared to take it on admitted to being flummoxed a little. And then won over.

Back in 2011, TBW’s interest hadn’t yet been registered and Poor was still in production of the audio of Michael reading the work for public presentation. TBW Books publisher Paul Schiek has talked about the production of Assignment No.2, but Nigel Poor less so. This is the back-story to one of the most unique photo books of recent years — a book that combines fine art and fine design with an earnest recognition of a social justice need.

–

Scroll down for the Q&A.

–

Q & A

PP: How did you come to teach at San Quentin?

Nigel Poor (NP): I was always interested in teaching in a prison, and I just really never had the time to do it. While I was on a sabbatical [in 2011] I got an email from the Prison University Project saying they were looking for someone to teach art appreciation. I thought it would be a perfect time to teach there and form a class around the history of photography. I really wanted to do something with Doug so we got together to write this class.

PP: What do you look at?

NP: The history of contemporary photography — focusing on the 1970’s to the present. The course is 15 weeks like a regular semester. We met once a week for three hours. We started with early photographers — August Sander, Walker Evans and Robert Frank just to put some context and talk about how these photographers are often quoted and we move forward and show people like Sally Mann, Nan Goldin, Nick Nixon, Wendy Ewald.

Doug Dertinger (DD): Nigel tended to teach about the photographs that dealt with people, portraits, and social issues. My photographs tended to be the ones that dealt with land use and then also media. We struck a nice balance.

DD: The first two classes were strictly on aesthetic language, form, how to experience images, how to talk about them. The first assignment asked them to describe a photograph that doesn’t exist, that they wished they had that would describe a significant moment in their life. In that way they would create a little story for us and we would get to know something about them but they’d also have to use all the language about how you talk about a photograph. It was a really wonderful way to get them to think about making themselves part of the story of the photograph. Even if a photograph isn’t about you, you can bring your experience to it. It’s not solipsism; it is a way of entering photography. The exercise allowed them to take emotional chances with photographs.

In later classes, in 2012, Poor printed out famous photographs on card stock and asked her students to annotate directly upon the images. Click the William Eggleston analysed by Marvin B (top) to see a larger version of it. Kevin Tindall analysed Lee Friedlanders’ Canton, Ohio 1980 (middle), and Ruben Ramirez looked at David Hilliard’s tripychs (bottom).

–

PP: Were there any issues with your syllabus? Did you have to adapt it? Omit anything? Compared say to here at Sacramento State?

NP: I always tell my students, wherever we are, that it is an NC-17 rating. I naively thought I could just show the same images in San Quentin [as at Sac State] but when we started going through the process we were told that we couldn’t show any images that had to do with drugs, violence, sex, nudity, and children. Which is about 95% of photography!

At that point, I wasn’t quite sure how that was going to work but Jody Lewen [Director of the Prison University Project] is an incredible advocate and she didn’t want to presume censorship — Jody wanted the burden of explaation as to why we couldn’t show a particular image to be on the officials of the California Department of Corrections. She set up a meeting with the with Scott Kernan, the [then] Under-Secretary of the California Department of Corrections, and the [then] warden of San Quentin Prison, Michael Martell.

Kernan and Martell wanted me to show all the images that I was using for the class. I basically give them a mini-course in photography from 1970 to the present. We talked for close to two hours. I ended up getting permission to show everything except for four images.

PP: Not the worst case of censorship then?

NP: No. It was kind of a triumph. And, it must be said, without their help — especially Scott Kernan — I don’t think we would have gotten the class in.

PP: Can you describe the philosophy for the course?

NP: The central idea is to expose students to photography but really ask them to think about it quickly in an accessible and emotional way. Nor Doug or I teach from a theoretical or academic point of view. We argue that the images exist and they come to life because of the conversations we have around them. Students learn basic things about framing, form, content, but I really want them to explore all the areas of the photograph.

At the beginning, I describe the photograph as something akin to a crime scene; we are detectives trying to piece all the visual clues together to uncover subtext — perhaps, even secrets of the images that maybe the photographer isn’t even aware of.

In 2012, Poor was shown an archive of 4×5 negatives of photographs made by the prison administration in the 70s and 80s. The amount of information attached to the images is minimal. Poor broke the archive into 12 loose categories. One from the ‘Violence & Investigations’ category (top) and one from the ‘Ineffable’ category (bottom).

–

PP: Let’s come back to that. Because I want to bring Doug in here. Doug, what did you think when Nigel asked you to co-teach this program inside San Quentin Prison?

DD: I thought great. My parents are doctors and spent the last five years of their careers teaching at Federal Prison System. I taught in prison back in 1993 — one summer just general education stuff. So, when Nigel said that she was going to do this, well, I knew I wanted to partner with Nigel and thought it would be fun, in a way, to see what the what’s going on inside San Quentin.

PP: How do these students fair compared to your students in *free* society?

NP: They really understand the power of education and the importance of being present. I never had a student fall asleep at San Quentin or look at me with that blank expression! They were so hungry, open to conversation. It makes you worry about finding that same intensity outside of the prison setting.

DD: The men they already knew what they were about in a sense and so they came to the class with questions about photography and they understood that photography could reveal the world to them in ways that they were hungry for. A lot of students that I’ve had outside are still trying to figure out what they’re about and they haven’t yet come to their own necessity.

And, some of the men [in San Quentin] somehow understood that learning to talk about images, learning to see the world in a more complex way, could actually change them. I wish there was a way that didn’t sound trite to explain it but I could see transformations in them from the conversations that we had. Every Sunday when I left teaching there I would drive home in silence just contemplating the conversations that we had and how I felt I was becoming a better person for spending time with them. I would like to humbly think that they were too. It was a real back and forth.

Was it Wordsworth that said the imagination is the untraveled traveler? It seemed like when we went to class we all went on these journeys that were very significant for all of us. They were ready to travel.

In Nigel’s final class, she asked her students to annotate on print outs of photos from the newly discovered prison archive, in a manner similar to that they had with famous photographs from the art historical canon. Above are two examples.

–

PP: Earlier you mentioned Sally Mann. I presume a photographer that the authorities think is controversial, a photographer that wider society considers controversial and divides opinion. How did the discussion about Sally Mann’s work pan out?

NP: Some of them definitely had questions about the intent: Why would the mother want to photograph her three children romping around naked on their beautiful farm? But what I wanted to talk about how those images are highly staged and stylized. They’re not documentary images of how her children grew up. They are images about maybe desire about childhood, maybe the photographer inserting herself very clearly into these images. What is Sally Mann saying about the complexities of childhood or how children do have sexual feelings and act out in various ways? The images are about creating a tableau in a sense. It isn’t just about this mother who may have made images that made her children uncomfortable; it’s about creating stages to talk about emotional states of being.

PP: Well, I would think that many of the students are interested in notions of fact, truth, whether you can trust an image. Apart from the body, ones word is pretty much all you have when you’re incarcerated.

NP: We had a discussion very early on about the image always being a fabrication. It’s one person’s opinion putting a frame around the world and we always have to keep that in mind whether it’s documentary work or artist’s work. A lot of them got upset about that because I think they wanted to trust that something was reliable and truthful.

NP: And that may reflect a little bit on what happens to them, as people give evidence, or they want to assert their innocence, or not necessarily their innocence but how something unfolded in their life — this idea that everything is flexible and fluid was a little bit unnerving at times. They couldn’t look at the picture and think that’s exactly what the photographer meant and a few of them got prickly about it. It would come up off-and-on, you know. Can we use the word truth in reality when we’re talking about images and then by extension can you use those words when you’re talking about your own experience?

DD: That was a continuing topic throughout the whole semester. It was interesting too that they I don’t know how to describe it but they knew when they looked at a picture that there were all these elements in there. They explained it to us once: They get one picture from home once every 6 months, they pour over every detail of it and the desire is to create a narrative that they can fully believe and fully immerse themselves in. It was hard for them to understand that at first, at least, that there could be five different opinions about what a photograph was and each one kind of had equal weight.

Detail of Assignment No.2. Courtesy TBW Books.

NP: We don’t have a truth to give [the prisoners]. We’re going to give them our experience and talk about how we see the pictures but we’re going to learn something from them by the way they interpret images. I would see a photograph in a different light, often, after I heard what they had to say about it. I was the teacher in the classroom but it was very much about the power of group conversation. You have to outline what you want to discuss but you never quite know where the conversation’s going to go and I think that gave them a sense of power.

DD: I wonder if it was us not being, in a sense, “guards of meaning” that allowed them to say, ‘Oh, Nigel and Doug can be trusted to be privy to what we think, and they’re going to let us say things, and they’re going to correct themselves in relation to what we’re saying. We can participate, we have equal voice.’

PP: What do your students have to contribute to society?

NP: Before you have an experience in prison as a teacher or someone who’s going in as a civilian volunteer, prisoners are a group of invisible people. Even though I think I’m a thoughtful person, I had assumptions from what I read in the paper, in movies, in news.

PP: What you saw in photographs?

NP: Yeah! That these are going to be scary men, that if you turn your back are going to hurt you, that they’re animals they need to be separated from us and that they’re one-dimensional.

PP: Not so?

NP: When you go in there and you start talking and you see that these are complex, fascinating, thoughtful people; they’re citizens. They are part of our society. Yes, some of them have done terrible things but we have to think about reform and education, and the huge issues of, yes, redemption and forgiveness. How do we deal with those things? I think the only way you can thoughtfully talk about rehabilitation and forgiveness and make change is if you have a personal experience in there — you’re going to change your mind.

Details of Assignment No.2. Courtesy TBW Books.

NP: We need to find ways to use what’s in there to contribute to our society — to tap their experiences and thoughts. I became a better person by going in there and spending time. I learnt what it means to be human.

PP: That is similar to the feedback that I’ve got from other educators who’ve worked in prisons. Do you feel you are a conduit to the outside world. Do you have an added responsibility to share these stories, to share these men and their experiences with the wider public?

NP: I’m a pretty shy person and sometimes it’s difficult for me to talk at parties or whatever. But, now, I call myself the San Quentin bore. All I want to do is talk to people about this amazing experience, what these men are like. I feel very strongly about it, it’s not about me; it’s about this world that’s veiled and it’s about these men that are made invisible.

PP: You are not only a teacher, you are now an advocate. I hear you’re about to give a student the opportunity to “present” his work to the public?

NP: One of the assignments we had for the students was to give them two images from by two different artists and to ask them to analyse them. The only things the student knew about the works were the artists’ names, the dates, and the titles.

One student, Michael Nelson was given an image from Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theater series and a Richard Misrach image of a drive-in theatre from his Desert Canto series.

Richard Misrach. Drive-In Theatre, Las Vegas (1987), from the series American History Lessons.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. La Paloma, Encinitas (1993), from the series Theaters.

NP: While Michael was doing the assignment he was put in the hole, isolation, segregation for four weeks. He wrote an amazing paper talking about those two images. So beautiful that I wanted to get it to Richard Misrach which I was able to do and Richard was blown away by the piece.

Richard had been invited to be part of an event in San Francisco called Pop-Up Magazine which invites 20 to 30 different artists, once a year, to tell six minute stories. Richard’s idea was to read the paper that Michael wrote which was incredible. BUT! Then we started talking about it more, the organizer of Pop-Up decided he wanted Michael to read the paper. So, I went into San Quentin and recorded him reading his beautiful paper.

PP: Fantastic.

NP: It will be edited together. Richard will introduce it, show the two photographs and then play the recording of the student reading. It’s thrilling that this man who’s been in prison for more than half of his life is going to have the chance to be heard by 2,500 people.

PP: Nigel, Doug, Thanks so much.

PP: Nigel, Doug, Thanks so much.

NP/DD: Thank you.

ASSIGNMENT NO.2 (2014)

In an edition run of 1000, Assignment No. 2 will give many more people the opportunity to experience Michael’s words.

By Michael Nelson, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Richard Misrach.

12 x 9.5″ closed / 12 x 30″ open.

20 pages.

2 full color plates.

All proceeds go to the Prison University Project.

Buy here.

–

I wanted to congratulate three artists who were recently named as 2015 Fellows at A Blade Of Grass.

Sol Aramendi, Nigel Poor and Dread Scott are three of eight fellows who’ve received $20,000 each to pursue ongoing art projects that better the social, economic and cultural capital of the people with whom they collaborate. I have spoken to the three of them at different points in the past and applaud ABOG on its selection.

This is also a good moment to get A Blade Of Grass on your radar. ABOG has emerged as a thoughtfully-networked, well-advised, organisation with intent to put large amounts of money into the hands of responsible artists who work directly with communities, for dialogue and for change. The fellowships come with fewer strings attached than other funds, thus entrusting artists with the scope and freedom needed for socially engaged projects.

WORKS

Sol Aramendi will use the fellowship to develop Apps for Power — a smartphone-based app to help workers fight wage theft and restore power to the worker by allowing him or her to safely share worksite experiences, report wage-theft and flag abusive employers. The idea for the app emerged from Aramendi’s discussions with immigrant day laborers. Aramendi has brought in artists, organizers, developers, and lawyers to realise the app which makes transparent a previously exploitative and alienating system.

I interviewed Sol recently: Tapping NYC Migrants’ Creative Energies Through Street & Studio Photography

–

Nigel Poor‘s ongoing San Quentin Prison Report Radio Project will benefit greatly from committed funds. Poor started her work in California’s most famous prison, co-teaching a photo history class inside, with Sacramento State University colleague Doug Dertinger. Later, Poor conducted workshops in which she asked prisoners to annotate San Quentin Prison’s own archive of photos.

Working with incarcerated students changed Poor; she wanted others outside the prison walls to meet these articulate, curious and intelligent man. With a longtime interest in audio, Poor reasoned that radio was the best option. Existing broadcast equipment existed in San Quentin and a local public radio was keen to broadcast Poor’s collaborative efforts. She works with Brian Acey, Greg Eskridge, Jun Hamamoto, David Jassy, Jason Jones, Adnan Khan, Harold Meeks, Tommy Shakur Ross, Louis A. Scott, Shadeed Wallace Stepter and Earlonne Woods. Participants are trained in all aspects of audio and radio production to make stories that are complex and challenge reductive stereotypes, while also providing meaningful work for men who are serving life sentences.

I interviewed Nigel and Doug Dertinger in 2011. (Later this week, I’ll be publishing the full edited text.)

–

Dread Scott is making Slave Rebellion Reenactment (SRR), a reenactment of the largest rebellion of enslaved people in American history. SRR will re-stage and reinterpret Louisiana’s German Coast Uprising of 1811, involving hundreds of re-enactors on the outskirts of New Orleans, in the same locations where the 1811 rebellion occurred.

In the past, I’ve featured Dread’s Lockdown and Stop, about Stop & Frisk in NYC and Liverpool, England. And, by chance, I stumbled upon his well-received, one-time-only performance On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide under the Manhattan Bridge in October 2014. Me and hundreds of school-kids and scores of bemused office workers on lunch-break.

–

BIOGRAPHIES

Sol Aramendi is an artist and educator. A vocal agent for social change, she founded Project Luz, a nomadic physical and conceptual space for immigrant communities to learn, create, and communicate, allowing for the greatest agency and collaborative opportunity for all of the participants. Photography is the main tool of engagement. She holds an MFA in Social Practice from Queens College, an Arte Util Residency at Immigrant Movement International, a fellowship from the Smithsonian Latino Museum Studies and has just completed a CORO Immigrant Civic Leadership program from the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs.

Nigel Poor is a San Francisco-based artist and photographer and member of the San Quentin Prison Report collective. She is a Professor of Photography at California State University, Sacramento.

Dread Scott makes revolutionary art to propel history forward, working in a range of media including performance, photography, screen-printing, video, installation and painting. He has exhibited and performed at numerous institutions, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Contemporary Art Museum Houston, the Walker Art Center and BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music) and has been written about in numerous publications including The New York Times, Art In America, ArtNews, ArtForum, Art21 Magazine, The Guardian, and Time.

A Blade Of Grass provides resources to artists who demonstrate artistic excellence and serve as innovative conduits for social change. ABOG evaluates the quality of work in this evolving field by fostering an inclusive, practical discourse about the aesthetics, function, ethics and meaning of socially engaged art that resonates within and outside the contemporary art dialogue.

Nigel Poor (left) and Doug Dertinger (right).

The intersection of photography and prisons doesn’t always manifest as a photographer pointing his or her lens at incarcerated people.

Photography – or more specifically the discussion of it and associated issues – can enter relationships, education, exchange. Both the practice and theory of photography can be taught and learned within prisons.

Last September, Nigel Poor, Associate Professor of Photography at California State University, Sacramento contacted me to tell me about her volunteer role teaching the History of Photography at San Quentin State Prison. I was blown away. Never before had I come across a photo history class taught behind bars. Immediately, I made arrangements to meet Nigel and her co-teacher and fellow CSUS professor Doug Dertinger.

As faculty, Poor and Dertinger adapted their existing CSUS syllabus, covering photography from 1970 to the present. However, the California Department of Corrections understandably wanted veto power over slides presented during the course.

Depictions of drugs, violence, sex, children, nudity are problematic for prison administrations … “Which is about 95% of photography,” points out Poor.

Poor and Dertinger were helped out by the experience of Jody Lewen, director of the Prison University Project at San Quentin. Lewen is insistent that PUP teachers do not self-censor, but respectfully present their preferred teaching material and allow the burden – and justification – for any censorship to fall upon the prison administration.

The interaction, therefore, was unorthodox but successful: Poor presented her entire 12 week course to Scott Kernan, Under Secretary to the CDCr (now retired) and to Mike Martel, the then Warden at San Quentin … in two hours!

Of the entire course, only four images were deemed unsuitable, a surprising but pleasing result that Poor describes as “a triumph.”

With Poor focusing on portraits and Dertinger focusing on land use and media, they quickly schooled their students in line, formal composition and leapt from there into sophisticated readings of images.

“I told them the photograph is like a crime scene,” says Poor, “and it is ours from which to draw evidence.”

Poor and Dertinger talk about what a life-affirming experience teaching inside proved to be; about how the men in San Quentin were the “most present students” they’ve ever taught; how invigorating it is to have a passion that isn’t only about oneself; and about the responsibility to educate people in free society about the potential of incarcerated people, a “veiled population.”

“They were ready to travel,” says Dertinger of the students’ willingness to unleash their own emotions and imagination upon photographs read.

Interestingly, the idea that the photograph was not – is not – a reflection of truth was disconcerting for the many of the students. Obviously, the reliability, or not, of narrative and testimony may have had a more profound effect on the reality of their lives as compared to others not subject to the criminal justice system. If you can’t use the language of truth and reality when discussing photography (popularly considered to be objective), then can you use those concepts when discussing your own life?

We end the conversation on a high note: One of the students wrote a comparative analysis of Richard Misrach’s Drive-In Theatre, Las Vegas and one of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theatres. He wrote a 9-page essay during a four-week solitary confinement stint. He concluded Misrach’s work is about space; Sugimoto’s about time.

So impressed were Poor and Dertinger they got the essay into Misrach’s hands … and he read the essay to an audience of 2,500 at the November Pop-Up Magazine Event in San Francisco.

LISTEN TO OUR CONVERSATION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE