You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Activist Art’ category.

The fight against mass incarceration takes many forms: from protesting outside prisons, to blocking jail construction, to journalism that reaches inside, to hearing prisoners’ voices, to making oneself aware of gross abuses, to viewing the most gruesome pictures, to letter writing, to education and more. Sometimes the fight requires coming together and “hacking” the system by sucking up costs collectively and *joyously* paying bail.

The Philadelphia Community Bail Fund is celebrating creativity, raising consciousness, and tackling unjust bail policies by paying them. The group is identifying poor people who needlessly languish in jail while they await trial. In the past three weeks, and at the time of writing, Philadelphia Bail Out has raised $98,000. A stunning effort.

No doubt, this short term *solution* also raises a longer term debate about the unfairness about cash bail and can potentially drive future positive change. Thousands of people have donated art, time, skills, money: small contributions that have amassed to a large reserve of cash to bring mothers home for Mother’s Day.

In order to secure release before Sunday 12th, Philadelphia Community Bail Fund has marked today as the last day to ensure your money goes to the release of women on the first round of bail outs on Thursday. Keep donating though and more bail outs will occur through next week.

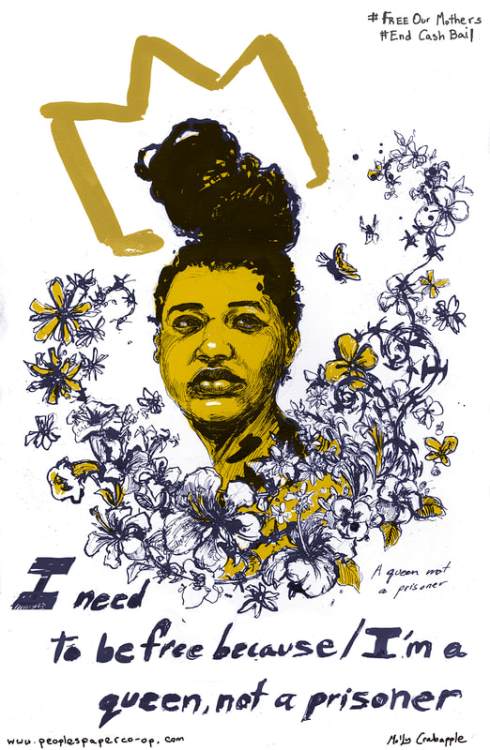

FREE OUR MOTHERS POSTERS

Among the dozens of community-group-partners, I want to give a shout out the the People’s Paper Co-op, a women led, women focused, women powered art and advocacy project that promotes women in reentry as the leading criminal justice experts. PPC “uses art to amplify their stories, dreams, and visions for a more just and free world.”

People’s Paper Co-op has partnered with Philadelphia Community Bail Fund to create limited edition poster prints for you to buy and all the money goes to getting cis and trans women out of Philly jails. The posters are made of shredded and pulped criminal records that have been expunged.

Artists include Etta Cetera, Kate DeCiccio, Micah Bazant, Molly Crabapple, Molly Fair, Nile Livingston, Rose Jaffe, Shoshana Gordon and Sanya Hyland.

“We need each other,” says Hyland. “We need community, in order to make the fundamental transformations necessary in our society. The women behind “Mama’s Day Bail Out” have organized something powerful and transformative, showing we do ‘have the power to transform our world’, but ‘we can’t do it alone’.”

Go buy art, or simply donate, get mums out of jail and support true community organizing.

Listen to the track list on Spotify

Some years ago, my hometown community back in Britain was hit hard by the suicide of a friend. He was a musician on the rise and his loss was felt across the isles. Out of the tragedy came a resolve to speak openly about mental health struggles. Depression and suicide and difficult issues to discuss but I think neglecting the realities of the former leads to higher risk of the latter.

Consequently, We Are Hummingbird (WAHB), a community of music lovers who spread awareness of mental health within the music industry, was established. Among the many initiatives WAHB coordinates, The Playlists are my favourite. Depending on which stats you take on, there are 12 or 13 individuals who commit suicide in the UK each year. Therefore, 12 or 13 track on each playlist.

These lists come from far and wide, from music celebs and quirky amateurs with lots of love to give. They are weekly installments of others’ passions, joys, music secrets and beloved taste. The songs that centre you, the songs that take you elsewhere, the songs that bring comfort.

I was happy to answer the invite to make a playlist, but it’s nearly impossible to reduce your favorite things about music down to a track list of 13! To make the decision-making easier, I limited myself only to artists who originated or were/are based, on the U.S. west coast. Over the years I’ve lived in San Francisco, Sacramento, Oakland, Portland and Seattle.

The west coast a long way from my UK roots, so the music these places conjure is both discovery and bittersweet reminder that I’m far from my Brit-rock Indie teenage self; the nineties were when I felt most connected to people through music. I’m listening to songs all day long as I write and edit and grade papers. Pinging far away friends with new tracks and emerging artists keeps me pucker and in touch.

Making this track list was a trip. It’s for you and it’s for me, it’s for friends and strangers, it’s for Matt’s memory and it’s for a future without stigma and unnecessary struggle around mental health. I hope you can dig this peculiar mix of classic rock, early punk, spiritual jazz, summer rap, slide-guitar instrumental, doo-wop and singer-songwriter bliss.

WE ARE HUMMINGBIRD PLAYLIST

Listen to the track list on Spotify

For no particular reason, in chronological order:

Heart – Barracuda (1977)

Let’s start this thing with some glorious fun. Amy and Nancy Wilson are goddesses. From Seattle, Heart was making music 20 years before grunge defined the city. Nancy plays mandolin. Amy’s vocal range is filthy. WILSON WILSON 2020.

The Cramps – The Way I Walk (1979)

Formed in Sacramento, the punk-psychobilly The Cramps fused rock’n’roll riffs with yelps, whoops, Hawaii licks and a fuck-you-farce-view of society. They inspired other favorites of mine The B52s and Thee Oh Sees.

The Go Go’s – This Town (1981)

One of the most successful all-female bands in history. Belinda Carlisle in her early pomp. Pop signatures to die for. Clap machines. The Go Go’s set the sound-motifs for a decade of eighties movies.

Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda – Rama Rama (1987)

Coltrane is not an artist easily understood by a single track. Her albums are complete journeys that demand surrender–make time for Universal Consciousness (1971), Illuminations (1974) and Eternity (1975) on vinyl or cassette. The multi-instrumentalist’s journey is the quintessential tale of west coast reinvention. Following her husband John Coltrane’s death, Alice moved out to Malibu, embraced Eastern mysticism and founded an ashram. ‘Rama Rama’ doesn’t feature Coltrane’s signature harp, but her prominent throaty chant-vocals (also unusual) run deep. Pause to consider that, at the same time, just an hour away, N.W.A were recording their landmark album ‘Straight Outta Compton’.

Rodney O & Joe Cooley – Everlasting Bass (1988)

Hip hop at its most innocent. Rodney and Joe never made it big but with this late-eighties signature track, they laid the foundations for West Coast hip hop and rap (especially Dre and Snoop).

Coolio – Fantastic Voyage (1994)

It’s a song about driving across Los Angeles to the beach and all that that entails. The video is amazing: Coolio transports hundreds of beachgoers in the trunk (boot) of his car.

Stephen Malkmus & The Jicks – Pink India (2001)

Generally regarded as his most accessible, rounded single, Pink India namechecks Stoke-On-Trent and is, I think, an argument against imperialism and war.

Magic Magic Roses – Memory Palace (2012)

“You deal in space, I deal in time. We build a, a constellation.” Nuff said.

La Luz – Sure As Spring (2013)

This four piece from the Seattle suburbs blew onto the scene in 2012ish. They’ve since charmed everyone with their dreamy, surf-rock that channels Mexican telenovelas and grindhouse soundscapes. Picked an oldie, but they keep upping the ante. Most recent album Floating Features (2018) is top.

Marisa Anderson – Sinks and Rises (2013)

I first heard Anderson play at a book-reading party. That’s a party at which speaking is forbidden and everyone kicks it on beanbags catching up on their reading. It was summer, it was hot, everyone was in shorts and Anderson put out blues and lapsteel into the air, over the fences, and across the neighbourhood. Portland legend. Soon to be a global legend. This tune is about a day at a swimming hole.

Lithics – Lizard (2017)

Low energy, punk-y rock. Portland-based four-piece. Insistently different. Sparse vocals. I can’t decide if they’re ordinary or genius and I’ve seen them play at least 5 times. Lithics make the list because they still have me confused.

Ill Camille – Black Gold (2017)

Unembellished rap over sampled soul vocals. Represents the current renaissance in Los Angeles being made by young artists with new sounds. Sit down, shut up and listen. Strong AF lyrics. So good.

Ian William Craig – A Single Hope (2017)

Based in Vancouver, Craig is Canada’s version of Olafur Arnalds. Indulge in melancholic loops, gentle strums, choral voice and electronic stuff. Songs are mood makers, yeah?

Listen to the track list on Spotify

Follow We Are Hummingbird on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

I’m talking in public next week.

For this Creative Mean convening, artists Rita Bullwinkel, Sam Vernon and I will present on the theme of Relationships. 15-minutes per person, followed by a Q+A/panel chat with the audience.

I’ll be talking about my relationships in the classroom at San Quentin. I’ll reflect on how the ideas about photographs that my students and I hold have shifted and shaped. There’s no scoop here, just observations. There’s no drama, mostly quiet gratitude.

Event is 6pm-8pm on Wednesday, April 10th, at Heath Newsstand, San Francisco. Here’s a map. Here’s a Facebook event page.

It’s gonna set you back $15 so I advise you get there bang on 6 and get your fill of Tartine scran, Fort Point booze and chocolate before you’re asked to sit at 6:30. Dang, they’re even giving away Aesop soap, to which I was a convert in 2017.

‘OPERATION JURASSIC’ BY PABLO AND ROXANA ALLISON

Brother and sister Pablo and Roxana Allison were separated for five-and-a-half months from late 2012 through spring of 2013. Pablo was locked up in London for criminal damage after being prosecuted for graffiti writing on trains. Pablo was one of several defendants sentenced as a result of Operation Jurassic, one the UK’s largest cases brought against artists using train carriages as their canvas. Since, the siblings have worked on putting together a visual record of the time and their emotions. The resulting book Operation Jurassic, published by Pavement Studios, just hit the stands. I wrote an introductory essay which I am pleased to republish here.

Scroll on!

A WARM THREAD

This book is a thread. A warm thread spun by two siblings during one’s incarceration. These images, conceived during months of separation and crafted during more months of house arrest, emerge from the worry and dislocation imprisonment brings. Born of necessity, these images are what Pablo and Roxana Allison did, dreamt up and fabricated; emotional twine that kept them sane and connected both.

As one in a cohort of graf-writers targeted by Operation Jurassic and done on charges of conspiracy and criminal damage, Pablo saw his conviction coming. It was likely he’d get a custodial sentence. Prior to the trial, he and Roxana decided that images could graft the space between them. He’d draw and describe scenes inside prison while she’d document her isolation at home. They’d plan photo-shoots for when he got out to capture what he couldn’t while inside. For painting trains, Pablo was locked up in November 2012. Roxana, while not entirely sympathetic toward his graffiti at that time, was horrified that he’d get sent down for his art. Together they resolved to come through it with a visual record. He served 5-and-a-half months in Wormwood Scrubs and HMP Brixton followed by one year, at home, under curfew with an electronic monitor strapped to his ankle.

This book is woven through with detachment. Doleful figures cut lonesome shapes—veiled, obscured, there but barely there. Sometimes only a shadow. Interior details and still-lives serve as descriptors of halted lives. Scratched through with twilight, bisected by lines and tree limbs, these photographs edge toward a shared emotional territory, but they’re only placeholders of time lost. In that way, they double as evidence of Pablo and Roxana’s defiance. From a position of near zero control, they intended to shape an outcome. These images establish their testimony in spite of, and in challenge to, the court proceedings, prosecution arguments and criminal narratives of British Transport Police (BTP) and the presiding judge. A warm, human thread of struggle spun from the dehumanising reaches of prison and house arrest.

Initiated in 2003, Operation Jurassic was one the largest prosecution cases ever brought against graffiti artists in the United Kingdom. Pablo and nine others were arrested in 2010. Pablo was one of five who consequently, in November 2012, faced trial for criminal acts perpetrated between 2005 and 2009. At the outset, the prosecution detailed upward of $10 million in damaged infrastructure but at trial only made a case for $1 million worth.

Potential punishments for graffiti-related crime in the UK is high. The BTP “Graffiti Squad” went after eight members of the DPM crew with Operation Shuttle, and in 2008 secured jail sentences of 12 to 24 months for all. In terms of the cost of the operation (£1 million to the taxpayer) and convictions (imprisonment), Shuttle set precedents of which Pablo and his cohorts later bore the brunt. All for putting some paint on some surfaces.

Led by Detective Constable Colin Saysell, the BTP Graffiti Squad went to war on graf-writers. During his 30-years as a copper, Saysell has helped convict 300 artists. Including Pablo. But his exacting approach is out of step with the British public who laud mainstreamed graffiti artists such as Banksy and Ben Eine. (Famously, in 2010, David Cameron gave Barack Obama a Ben Eine piece as a diplomatic gift.) Compared with law enforcement agencies abroad that don’t imprison graffiti artists, Saysell is an extremist.

Furthermore, compared to public education and youth outreach, Saysell’s hardline stance is bizarrely contradictory; murals and tags are used as an art-medium with which to engage city-kids’ creativity. A charity once took a double-decker bus into Wormwood Scrubs where members of the DPM crew painted it! Roxana wasn’t the only one staggered by Pablo’s imprisonment. Guards and prisoners alike couldn’t believe that, for making art, he was banged up alongside men who had murdered and maimed.

“Have you met any killers yet?” asks Antonio Olmos, photographer and mentor, in a letter to Pablo. “Anyone interesting like a member of Al Qaida or a dress designer? I imagine a lot of creative people are in prison…” On the inside, Pablo’s monochromatic, A4-sized sketches and notes are a far cry from his hulking, clacking train-car surfaces on the outside, where he would stalk yards for days in preparation for a night of painting.

Once inside, Pablo experienced a shift in his creativity. He felt his mind slow and the down-tempo pace worked because apart from writing and drawing he had little else to do. Time was spent on mailed offerings to friends and family. It’s almost too obvious to state that letters are lifelines for prisoners, but this book is built on the insistence of connections maintained, feelings felt and testimony spoken.

In this book, time and space are deliberately confused. Pablo is behind bars and then half-submerged in the Pacific Ocean. A prison sits in mid-winter and then, pages later, peeks from behind the full foliage of mid-summer. Some images reconstruct the confines of cell. Another the view from the back of a “sweat-box” custody van—a photograph that could never be made. Pictures of held hands and tired glances might be from before sentencing, or from the visiting room, or made during post-release house arrest. We have entered a chronological fog that mirrors the emotional fog endured by Pablo, Roxana and their family.

Photos of actual prison cells exist too, but how can that be? Pablo did have a camera in Wormwood Scrubs but not during his time as prisoner. In 2005, at the request of a local council member, a teacher from Hackney Community College asked Pablo and fellow students to visit the famous prison and make images for Prison Me, No Way!, a deterrent program designed to show young people crime’s causes and penalties. (Ironically, the British Transport Police is a partner of Prison Me, No Way!) Pablo kept those images, but never imagined he’d revisit the canteen, cells and tiers as an inmate. In these pages, site and sights (spaces and time) loop back on one another; exile has its own haunting feedback.

The pages of Operation Jurassic seem drained of blood. Understandably so. Roxana and Pablo’s lives were gutted to a great degree. Photographs flatten the world. Two dimensions tend to fail the fullness of life. Frustrated acceptance and silent screams run through these images. In some ways it is remarkable that Pablo and Roxana even wanted to return to their anemic limbo, let alone depict it.

These photos, legal documents, letters, emails, drawings and diary extracts bottle the soup of inconvenient memories that Pablo and Roxana cannot leave behind, nor that they want extinguished. From raw emotion and these memories, they grew. Despite the grey spectre of institutional control and despite the slowed pulse of the carceral clock, this book is Pablo and Roxana back in control. It is a warm thread. It is a gift too. Imagination and pictures, letters and sketches were what they had. Now, it is what we have.

Operation Jurassic

Pack includes:

100 page A5 Hardcover Book

36 page Staple-bound Zine

A3 Double-sided folded Poster

1st Edition of 100 copies. All books hand finished.

Follow Pablo on Instagram and Roxana on Instagram. Take a peek at Pavement Studios‘ website and peep them on Tumblr and Instah too.

OPENING REMARKS

I’ve stated it before but not often or forcefully enough: The LGBTQ community nurtures many of the most effective and motivating voices in the fight for prison abolition. LGBTQ people are frequently subject to the harshest and most dehumanizing treatment at the hands of the prison system. It is from this position that activists and formerly incarcerated individuals have mobilized against the prison industrial complex.

In the news, it is the circumstances of transgender people in prison that are most often described and decried. For clear reasons: imagine being held within a male facility when you identify as female. Or in a female facility when you identify as male. Read up on the situations of Marius Mason and Vanessa Gibson. In Pittsburgh, Jules Williams, a transgender woman suffered sexual and physical assault and harassment multiple times while detained at the Allegheny County Jail, a mens facility.

Very, very few prison or jail systems place transgender folx in facilities where they are free of victimization and predation. During her three years of incarceration in the Georgia Department of Corrections, Ashley Diamond was repeatedly assaulted, once after GDC officials placed her in a cell with a known sex offender. Diamond took the radical step to appeal directly to the public via “illegal” YouTube videos from her prison cell made on a contraband smartphone.

Diamond won freedom following a lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the conclusion was that the GDC didn’t want to deal with the expense and supposed inconvenience of providing the hormone treatments she’d been on for 17 years prior to her imprisonment. Similarly, in California, Michelle-Lael Norsworthy was freed unexpectedly when her lawsuit for access to healthcare threatened the CDCR with huge medical bills. Shiloh Quine won the right for sexual reassignment surgery, but hers, all too unfortunately, was an exceptional case.

(For an instructive overview of the experience of female trans prisoners, read Kristin Schreier Lyseggen’s book Women of San Quentin: Soul Murder of Transgender Women in Male Prisons which details the stories of nine women, including Janetta Johnson, Tanesh Watson-Nutall, Daniella Tavake, Diamond, Quine and others.)

While transgender people are winning more and more hard-fought recognition in open society, prisons occupy the other end of the spectrum—closed, rigid systems unable to safely house the majority of prisoners and certainly unprepared and, more often, patently unwilling to recognize prisoners with gender dysphoria and their specific needs. (Trans issues are at the forefront in the military again. The regressive and punitive White House is banning transgender personnel from service. Unsurprisingly, DJ Pee-Tape is largely at odds with much of the military command.) Historically, the marginalization and criminalisation of LGBTQ people has funneled them into the criminal justice system, too. That point needs to be made.

Transgender prisoners are just one group within the LGBTQ community. Lesbians and gays face daily vilification within the criminal justice system. The tactics for resistance of different groups within the LGBTQ community necessarily vary in specific ways, but the enemy is common.

In a push back against the homophobia and transphobia embedded within the criminal justice system we should look to leaders such as CeCe McDonald, Dean Spade and Reina Gossett. Their intersectional critique of policing and prisons connects the dots between discriminations of all types. Prejudice and inequality exist within our society; certain groups, including LGBTQ and particularly LGBTQ persons of color, are valued less than others. The root causes for racism, sexism, imperialism, militarism are the same, and those root causes not only emerge out of capitalism but are, in many ways, its foundations. The complete abandonment of LGBTQ persons’ needs in prisons brings into sharp focus the fact that the systems, and our society from which they grow, deem this group more disposable than others.

“Prison abolition means no one is disposable,” says Reina Gossett. Exile is not a solution to the shortcomings of a society; exile allows wider discrimination to perpetuate.

“We should not model what the state’s logic is about who is disposable,” Gossett continues. “Challenging and dismantling structures of violence. [We need] relationships modeled on a different logic, not on the logic of white, heteronormative hegemony.”

Seen through a queer lens, the violence of the prison industrial complex is laid bare. Prisons are sites of waste and sites of survival; sites into which those outside the dominant norm are discarded. True to capitalist, carceral logic, the only economic benefits prisons bring about are for the state, law enforcement unions, corporations and craven politicians. We, the taxpayers, hand over this wealth at the expense of the lives and livelihoods of all those locked up. In the modern U.S., prisons are not about “time out” or rehabilitation; they’re about control in order to instill order. Prisons crush humanity and they assault diversity.

Prison abolition is about identifying structures of violence and working against them; about prefiguring a better world in which you want to live. In reviewing the book Queer (In)Justice (Ed. Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock), journalist and activist Vikki Law notes the authors’ contention that “deep-seated prejudices and fears of queer people cannot be dismantled via hate crime legislation.” Social attitudes are the strongest underpinning to a just society, not the latter-stage adjudications of the law.

“The authors say,” continues Law, “that ‘many of the individuals who engage in such violence are encouraged to do so by mainstream society through promotion of laws, practices, generally accepted prejudices, and religious views,’ and they note that homophobic and transphobic violence generally increases during highly visible, right-wing political attacks.

(For an introduction to community organising toward abolition, read James Kilgore’s recent piece Let’s Imagine a National Organizing Effort to Challenge Mass Incarceration.)

Prison abolition is about pushing back on all the structures that manifest the suspicion, dismissal and abuse of people who counter the white patriarchal status quo. That includes visual structures. That includes, as Critical Resistance states, “the creation of mass media images that keep alive stereotypes of people of color, poor people, queer people, immigrants, youth, and other oppressed communities as criminal, delinquent, or deviant.”

That is why Lorenzo Triburgo’s project Policing Gender is so important. Triburgo, a trans man, is not only advocates for the larger LGBTQ rights at stake, but also makes images that bring the weight of photographic history and analysis of images’ power to bear on his decision-making and design. His is a queer perspective. Policing Gender is enigmatic and beautiful and devastating. Triburgo’s personless portraits point us past what the images are in-and-of-themselves and toward a critique of what images have done in the past in service of, and to damage, LGBTQ-identified people.

I can make no apology for the length of these introductory remarks, because these photographs are built upon years of Triburgo’s conscientious thought, and on decades of queer activism by countless others. Context is important. From here, I’ll let Triburgo himself explain the conceptual underpinnings of Policing Gender and just add how grateful I am for our extended conversation. Scroll down for our Q&A.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): We first met in Portland around 2012 or 13. We published a conversation in 2014. At that time you’d just picked up research for a photographic project on the topic of mass incarceration. You explained then that you’d wanted to do portraits of families, but the warden explained that the visiting room had a program for such portraits. The idea was shelved for a while, as you made Transportraits, but you knew you’d come back to it. Family portraits are very different to these curtains and aerial landscapes. How did you get from there to here?

Lorenzo Triburgo (LT): When I began Policing Gender I collaborated with the queer prison abolition organizations Black & Pink and Beyond These Walls to become pen pals with over 30 LGBTQ-identified prisoners. I wrote and talked with my pen pals for months and months before deciding on what the project would entail visually.

Keep in mind that I also worked to gain access to various prisons and jails. I was doing my *photographer’s due diligence*. However, after getting inside, I thought, “F##k that. I’m not going to create photographs that could potentially strengthen the association between queer people and criminality.”

I kept obsessively thinking, “I want to make portraits, but not portraits. Portraits, but not portraits.” I was wracking my brain. The reasons were twofold.

First – ethically, as a queer person, feminist, and artist I am particularly sensitive to issues of representation and exploitation. I could have made the portraits but, to what end? How radical can a straightforward portrait really be? Would portraits of queer prisoners bring anything to the world besides an opportunity for viewers to gawp or sate their curiosity and voyeurism?

One of the hellish qualities of prison is the complete lack of privacy. Random administrators, politicians, teachers and students might make visits to a prison and get led on “tours” where they can peer-in on any prisoner through a tiny window and just watch. Did I want to replicate that experience with my camera lens? No.

Furthermore, how would I know for sure that I was getting informed consent from participants? In what world would our exchange be equal? Even more importantly, in what world would the exchange between any prisoner and viewer be equal?!

Secondly, conceptually, I felt my project demanded a complex approach that would embody the depth, pervasiveness, scale and abuses of the U.S. prison system. It needed to be more than a single-layered visual representation; more than a straightforward portrait.

LT: I started to think about making portraits with no figures.

What if instead of putting my incarcerated pen-pals on display, I go a quieter more contemplative route and conjure a sense of absence? The next step was to figure out what the figureless portraits would look like. I recalled a lecture by Cathy Opie where she cited renaissance portraitist Hans Holbein as a major influence. Holbein and Opie use fabric as a symbol of wealth, power and beauty.

PP: But to different ends.

LT: Yes. Opie appropriates formal aesthetics in order to queer the photographic portrait. I saw that I could use fabric and create connotations of portraiture and, for some of us, make a nod to queering the portrait through the use of form. It felt I’d found an answer to the inevitable imbalance of power between prisoner and viewer that I wanted to avoid perpetuating. Figureless portraits point toward this thorny ethical ground.

While thinking all this through, I was discussing my ideas with activists and researchers including Dr. Susan Starr Sered, co-author of Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility. Dr. Sered and I had a conversation that solidified my decisions.

PP: On your work’s figurelessness, an editor with whom I spoke recently referred to your work as “withdrawn”. It wasn’t a criticism per se, but I wonder about your reaction to that assessment?

LT: My pen-pals are trans and queer, and young and old, and out and not out, and coming out for the first time, and helping others come out for the first time all behind bars. I wrote and talked with them for months and months before deciding on what the project would entail visually. The decision to exclude people in the images is not ONLY about theoretical distancing from prisons and a challenge to photographic voyeurism. It’s also about anonymity for safety reasons and my pen-pals not always being able to come out without endangering their safety, and about recognizing that prisoners are a protected subgroup and not always able to give knowledgeable consent.

The figurelessness is about the absence of 2.3 million prisoners from society.

It’s difficult to communicate absence through photography but that was a risk I wanted to take. I believe we are at a stage when absence can be just as powerful as presence because there is so much photographic presence.

The work isn’t withdrawn. It’s emotional. It’s meditative. It’s quiet. I’m asking the viewer to take a minute and reflect: on their position in the world, on their assumption that they get to “see” whatever they want to see, and on the people who are missing from our society.

The lighting in these pieces was a meditative process for me. It was a way for me to process what I was learning about from my pen-pals. It’s not a vapid conceptual piece in reaction to the prison system. Each fabric represents a set of circumstances that was told to me by my pen-pals and is therefore named after them — each is a combination of their names.

PP: And what about the aerial shots?

The aerial images are about surveillance. The construct of imprisonment. The natural contained. Creating these was also an emotional process. I was in the hot air balloon …

PP: Wait! You were in a hot air balloon?!

LT: Ha! Yes. I photographed from a hot air balloon.

Balloons were an early method used by photography in the service of surveillance. During the U.S. Civil War, hot air balloons were used to create the first aerial reconnaissance images. I was looking for a way to undermine the idea of surveillance and to portray a grandiose notion of the ‘natural’. But once I was up there I couldn’t escape the feeling of my social position, the feeling of sadness and anger and unearned privilege and wishing that I could bring my pen-pals up in the air with me. The aerial photographs ultimately reflect these emotions and, metaphorically, the inescapable presence of surveillance.

All of my emotional experiences have a direct correlation to my conceptual interests in photography. It’s how I process the world.

I think about portraiture all the time. I feel the experiences of my various identities and ways I present myself to the world and the way I’m “seen”. I see oppression based on identities and I process that by creating photographs, and in the case of Policing Gender, audio art, too.

Photography is a way for me to make sense of the world and for me to present ideas to the world. These ideas are emotional as much as they are political and theoretical because I feel like I live them. I’ve had someone else’s camera pointed at me because I seemed “interesting” and it feels like crud.

PP: How are LGBTQ identified people affected by the prison industrial complex?

LT: Right now there are 1.6 million youth facing houselessness in the U.S. We know that 46% of these youth are LGBTQ identified. Add to that, cities across the U.S. are increasingly passing laws that ostensibly make it illegal to be homeless. Over the last ten years, there’s been a steady increase in the number of cities that have made it is illegal to lay down, sleep, or even sit in public and (in cities like Houston) to share or give food to people. Once queer youth are arrested and detained they are more likely to be sentenced to jail time and serve longer sentences than their non-LGBTQ peers.

We also know that people who have been arrested have a higher chance of returning to jail or prison. So, these youth grow up to be LGBTQ identified adults with a much higher chance of spending time in U.S. prisons. This is especially true for people of color, youth, immigrants, differently abled, and poor people. So, are queer people in prison because they are queer? If we look at the systemic level, rather than a matter of individual choices, the answer is yes.

PP: Which LGBTQ-focused individuals and organisations are working specifically and effectively against mass incarceration?

LT: The book Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex edited by Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith is an invaluable resource for just this question. It was published by AK Press soon after I began Policing Gender; this book came to me at exactly the right moment and is an invaluable resource.

Captive Genders includes first person narratives, research, and political analysis with an emphasis on writing from current and former prisoners.

I personally worked most with Black & Pink and Beyond These Walls.

Black & Pink is a grassroots organization that has been working in support of LGBTQ prisoners and towards prison abolition with nationwide chapters for over ten years. Their website is also an incredible resource. Beyond These Walls is Portland-based and is another grassroots prison abolition effort with a focus on supporting queer prisoners.

In the intro of Captive Genders, Stanley writes, “It is also important to highlight that women, trans, and queer people (specifically of color) have done much, if not most, of the anti-PIC organizing in the United States.”

Case in point: Miss Major Griffin-Gracy has been an activist for over 40 years and was the first Staff Organizer at The Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP). TGIJP is based in California and began as a legal project with leadership by formerly incarcerated trans women of color. Miss Major is recently retired from TGIJP but continues to be a badass inspiration to us all. (I recently saw her on the panel for the release of the book Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility at the New Museum).

The Sylvia Rivera Law Project, formed by civil rights activist and attorney Dean Spade in 2002, must also be mentioned here. SRLP provides legal aid to low-income trans, gender non-conforming, and intersex people and “is a collective organization founded on understanding that gender self-determination is inextricably intertwined with racial, social, and economic justice.”

PP: You once expressed an interest in photographing prison guards/correctional officers. Do you still?

LT: No, but I think someone should. The abuse that prisoners face at the hands of correctional officers is abhorrent — and — it is crucial to recognize that the job of correctional officer is basically designed to produce and enable a monstrous abuse of power. If we are to understand the prison industrial complex for what it is – an entire system of oppression upheld in part by the narrative that people of color, poor people, and queer people are dangerous – we also need to recognize systemic/social/economic conditions that lead someone to become an officer and the mental trauma associated with this job.

According to one study (Stack, S.J. & Tsoudis, O. Archives of Suicide Research, 1997) the risk of suicide for correctional officers is 39% higher than their peers in other professions and other studies show increased PTSD, divorce, and substance abuse. (See: Denhof, Michael D., Ph.D and Caterina G. Spinaris, Ph.D., Desert Waters Correctional Outreach, 2013.)

The effects of unchecked power, a career culture that encourages and rewards racism, homophobia, sexism, and xenophobia and corruption that goes all the way up the chain are traumatic. Hello Stanford Prison Experiment!?!

To go out on a limb, and to quote Michelle Alexander , I think of the job of the correctional officer as one manifestation of the many “efforts by the wealthy elite to use race as a wedge. To pit poor whites against poor people of color for the benefit of the ruling elite.”

Alexander continues, “Many people don’t realize that even slavery as an institution—the emergence of an all-Black system of slavery—was to a large extent the result of plantation owners deliberately trying to pit poor whites against poor Blacks. They created an all-Black system of slavery that didn’t benefit whites by much, but at least whites were persuaded that they weren’t slaves and thus were inherently superior to Black folks.” (‘The Struggle for Racial Justice Has a Long Way To Go’, The International Socialist Review, Issue #84, 2012.)

Keep in mind that people who take these jobs are predominantly working class, often with no other viable option for work because other industries have been (systematically) replaced by the prison industry in towns across the U.S. I feel myself holding my breath and my heart racing in anger as I say this.

PP: You have said repeatedly and in public that you’ll respond to any LGBTQ prisoner who writes to you. Kudos to you. That’s a serious commitment. It must also be quite the emotional experience—good and bad. Tell us about letter writing.

LT: So much here. I don’t know where to start exactly. In previous interviews I ducked the question out of fear of sounding schmaltzy, because it is super emotional and I don’t want to come off sounding all “we are the world” or like, neoliberal humanist or something.

That said, it has been fucking incredible.

There’s something astonishing about getting to know someone slowly, over time, through written word. How often do we have the opportunity to get to know someone completely from scratch? With no photo to go by, no list of basic likes or dislikes, not knowing their preferred name or gender, or where they are from. I got to know my pen-pals’ handwriting and that is a specific intimacy unlike any other type of exchange.

I never ask my pen-pals why they are in prison. Instead, I ask about what they think are the most pressing needs of LGBTQ prisoners and what they think an artist can do. Very often the response is that a way to share their stories and their truth would be a huge help. In the audio for Policing Gender you hear one of my pen pals say, “At least out there you’ve got cell phones to record this stuff [abuse by officers], in here it’s complete secrecy.”

I’m not interested in “giving voice”—my pen-pals all have voices! But I am interested in giving their voices a platform outside prison.

By not asking about why they were in prison I aim to, at minimum, create a space for my pen-pals to talk to someone who didn’t see them first as a criminal and second as a person. I challenged myself, to be honest, to allow myself to be vulnerable, to share my thoughts, and to allow our conversations to develop without pre-judgements.

We talked about the prison system of course, but we also shared our coming out stories, what it was like during high school, whether our family was religious, our siblings, our parents, their kids. Some of my pen-pals were younger than me and grew up in the “Glee era” while others were baby boomers and couldn’t imagine being accepted as queer when they were younger. One of my pen-pals was really into Shakespeare. I am not. And we would joke about that.

I love getting to know people and their stories—so it was just wonderful in that regard. I would also simply Google information and send it upon request. It is so easy to take our access to information for granted! I would send variations on photo assignments I give my college students, making them into creative writing or drawing prompts.

There was one person with whom I lost contact and that was devastating. The last I heard of her she had been raped, then left in solitary confinement for 24 hours, then finally taken to a hospital —four hours away—given antibiotics on an empty stomach, then driven back to the prison while handcuffed in the back of a van. If you’ve ever taken antibiotics you know that they are nauseating in the best of circumstances. I don’t like to talk about stories like this too much. They are important but I also don’t want to sensationalize my pen-pals’ suffering.

I wrote with over 30 people on a monthly basis for almost two years. I still write with a small number of people and I continue to pair every incarcerated pen-pal who gets in touch with me with someone to write with on the outside. So far I’ve connected about 40 people with new pen-pals.

PP: I know you’ve designed a course on gender and photo at SVA, so if it’s not revealing any too much info, can you give us a few important titles and articles from the course reading list?

LT: My course at SVA is a studio/portfolio course where we incorporate queer studies concepts in the development and critique of projects. (The class is offered online through SVA Continuing Education. Therefore, anyone interested in exploring these ideas in their artworks can register). I also developed a graduate level seminar that I teach online for Oregon State University with a focus on representations of gender and sexuality from a feminist perspective.

Here’s a greatest hits list of texts:

- Barthes, Roland. “Rhetoric of the Image.” Image, Music, Text. Ed. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 32-51.

- Blessing, Jennifer. “Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography.” Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1997. 7-38, 67-119.

- Halberstam, Jack. “Technotopias: Representing Transgender Bodies in Contemporary Art.” In a Queer Time and Place. New York and London: New York University Press, 2005. 97-124.

- Jhally, Sut. “Image-Based Culture: Advertising and Popular Culture.” Gender, Race and Class in Media: A Critical Reader. 3rd ed. Eds. Gail Dines, Jean M. (McMahon) Humez. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2011. 199-204.

- Lorber, Judith. “Night to His Day: The Social Construction of Gender.” Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994. 13-36.

- Mercer, Kobena. “Reading racial fetishism: the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe.” Visual Culture: The Reader. Ed. Jessica Evans, Stuart Hall. London: Sage Publications, 1999. 435-447.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Visual and Other Pleasures (Language, Discourse, Society). 2nd ed. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 14-30.

- Rosler, Martha. “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography.)” The Photography Reader. Ed. Liz Wells. London: Routledge, 2003. 261-274.

- Sullivan, Nikki. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. New York: NYU Press, 2003.

- West, Candace, and Don H Zimmerman. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society Vol. 1, No. 2. (1987): 125-151.

LT: I also want to give a shout out to these texts that strongly shaped my aesthetic and ethical decisions in Policing Gender:

- The Subversive Imagination: Artists, Society, and Responsibility, Carol Becker.

- Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 2011. Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

- Queer (In) Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States, Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock.

- Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith.

- Are Prisons Obsolete, Angela Davis.

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander.

- Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility, Susan Starr Sered and Maureen Norton-Hawk.

- Punishment and Social Structure, Georg Rusche and Otto Kirchheimer.

PP: Wow, thank you, so generous. So many new texts for me. Have you a resource list of organizations working in solidarity with LGBTQ prisoners?

LT: Absolutely, these are organizations as listed in the book Captive Genders:

All Of Us Or None

1540 Market Street Suite 490, San Francisco, CA 94102

415.255.7036 [ext 308, 315, 311, 312]

info@allofusornone.org

http://www.allofusornone.org

ACT UP Philadelphia

P.O. Box 22439, Land Title Station, Philadelphia, PA 19110-2439

actupp@critpath.org

http://www.actupphilly.org

Audre Lorde Project

85 South Oxford St., Brooklyn, NY 11217

718.596.0342

http://www.alp.org

Bent Bars Project

P.O. Box 66754, London, WC1A 9BF, United Kingdom

bent.bars.project@gmail.com

http://www.bentbarsproject.org/

Black and Pink<

c/o Community Church of Boston, 545 Boylston St., Boston, MA 02116

http://www.blackandpink.org

BreakOUT!<

1600 Oretha C. Haley Blvd., New Orleans, LA 70113

http://www.jpla.org

Critical Resistance

1904 Franklin St, Suite 504, Oakland, CA 94612

510.444.0484

http://www.criticalresistance.org

FIERCE!

437 W. 16th St, Lower Level, New York, NY 10001

646.336.6789

http://www.fiercenyc.org

generationFIVE

P.O. Box 1715, Oakland, CA 94604

510.251.8552

http://www.generationfive.org

Gay Shame

San Francisco, CA

gayshamesf@yahoo.com

http://www.gayshamesf.org

Hearts On A Wire

(for folks incarcerated in PA)

PO Box 36831, Philadelphia, PA 19107

heartsonawire@gmail.com

INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence

P.O. Box 226, Redmond, WA 98073

484.932.3166

http://www.incite-national.org

Justice Now

1322 Webster Street, Suite 210, Oakland, CA 94612

510.839.7654

http://www.jnow.org

LAGAI—Queer Insurrection

lagai_qi@yahoo.com

http://www.lagai.org

Prison Activist Resource Center

PO Box 70447, Oakland, CA 94612

510.893.4648

http://www.prisonactivist.org

Prisoner Correspondence Project

http://www.prisonercorrespondenceproject.com

Prisoner’s Justice Action Committee

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

pjac_committee@yahoo.com

http://www.pjac.org

Sylvia Rivera Law Project

322 8th Ave, 3rd Floor, New York, NY 10001

212.337.8550

http://www.srlp.org

Tranzmission Prison Project

P.O. 1874, Asheville, NC 28802

tranzmissionprisonproject@gmail.com

Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project

342 9th St., Suite 202B, San Francisco, CA 94103

415.252.1444

http://www.tgijp.org

Write to Win Collective

2040 N. Milwaukee Ave., Chicago, IL 60647

writetowincollective@gmail.com

http://www.writetowin.wordpress.com

PP: Brilliant. Again, thanks so much.

LT: Thank you, Pete.

How can images tell the story of mass incarceration when the imprisoned don’t have control over their own representation? This is the question Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood asks as editor of the latest Aperture (Spring 2018).

“Prison Nation” can be ordered online today and hits the news-stands next week. Devoted to prison imagery and discussion of mass incarceration, the issue presents a slew of works across contrasting genres — landmark documentary by Bruce Jackson, Joseph Rodriguez and Keith Calhoun & Chandra McCormick; luscious and uncanny portraits by Jack Lueders-Booth, Deborah Luster and Jamel Shabazz; insider images from Nigel Poor, Lorenzo Steele, Jr. and Jesse Krimes; and contemporary works by Sable Elyse Smith, Emily Kinni, Zora Murff, Lucas Foglia and Stephen Tourlentes.

Equally exciting is the banger roster of thinkers contributing essays, intros and conversations — including Mabel O. Wilson, Shawn Michelle Smith, Christie Thompson, Jordan Kisner, Zachary Lazar, Rebecca Bengal, Brian Wallis, Jessica Lynne, Reginald Dwayne Betts, Ruby Tapia, Zarinah Shabazz, Brian Stevenson, Sarah Lewis, Hank Willis Thomas and Virginia Grise.

I have an essay ‘Prison Index’ included which looks back on almost a decade of this Prison Photography website–how it began, what it has done and what it has become. I highlight a dozen-or-so photographers’ works that are not represented by features in the issue itself. I wonder how PP functions as an archive and what role it serves for public memory and knowledge.

MATCHING QUALITY CONTENT WITH QUALITY DESIGN

I’ve known for years that Prison Photography requires a design overhaul. This past week, I’ve moved forward with plans for that. It goes without saying that the almost-daily blogging routine of 2008 with which Prison Photography began has morphed into a slower publishing schedule. There’s a plethora of great material on this website but a lot of it is buried in the blog-scroll format. My intention is to redesign PP as more of an “occasionally-updated archive” whereby the insightful interviews from years past are drawn up to the surface.

It’s time to make this *database* of research more legible and searchable. Clearly, as this Aperture issue demonstrates, the niche genre of prison photographs is vast and it demands a more user-friendly interface for this website. I’m proud to be included in “Prison Nation” but know it’s a timely prod to develop Prison Photography’s design and serve the still-crucial discussions.

Get your copy of Aperture, Issue 230 “Prison Nation” here.

Thanks to the staff at Aperture, especially Brendan Wattenberg and Michael Famighetti for ushering and editing the piece through.

Answer by Torsten Schumann, from Germany

How do you describe your culture, your nation? Would you describe it differently to someone overseas? Would you describe it differently to someone in prison overseas? What if that prisoner overseas asked you not to use words but to use images in your response? These are not hypothetical questions, at least not for the men at Columbia River Correctional Institution (CRCI) in Portland, Oregon. Nor for their collaborators scattered across the globe who are involved with Answers Without Words.

Answers Without Words is a collaborative photography project by artists Anke Schüttler, Roshani Thakore and the Free Mind Collective (a group of currently and formerly incarcerated artists) based at CRCI that engages photographers and prisoners in a visual exchange.

Men in the Free Mind Collective have devised questionnaires for photographers in specific countries (see examples below). Participating photographers are requested to answered with images instead of text: Answers without words.

Questions for the former Yugoslavia and Switzerland.

Answer by Torsten Schumann, from Germany

You are invited to join in! Answers Without Words is currently looking for artists and photographers in Germany, Sweden, Norway, Belgium, Poland, Israel and North Korea particularly, but are interested in collaborators anywhere in the world. (See details below.)

Answers Without Words functions, in some ways, as a protracted, connected non-digital version of Google searching.

“The internet is a research tool we usually take for granted in our daily lives,” explain Schüttler and Thakore. “That access is lost in incarceration; prisoners are restricted in terms of what they can learn online. On the other side, not many people on the outside have access to direct information or a good understanding about what happens behind prison walls. Answers Without Words seeks to re-establish an analogue and personalized version of internet image research.”

“Answers Without Words creates a personal experience directly tailored for me, that enables my mind to take a trip abroad,” explains Tom Price, a participant in CRCI.

Questions by Tom Price.

The Answers Without Words team assesses collaborators “answers”, CRCI, Portland Oregon

The questions and photographs will culminate in two exhibitions, one inside the prison and one publicly accessible in Portland, Oregon in Fall 2018. A public lecture will be presented in conjunction with the exhibition as well as a publication about the project that will be available publicly.

“In collaboration with overseas artists, this project supports marginalized artists, consisting of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals, building ties between them, their communities, the world and art,” says J Zimmerli, a prisoner at CRCI.

In return for your images, you can then ask questions of your own about the men’s lives inside. A photography workshop in prison will create a counter round of answers without words from the prison back into the world.

“People always want to know what it is like in prison, we can share this information with them,” asserts Musonda Mwango, a participant from CRCI.

The Answers Without Words team workshopping image “answers” of their own, CRCI, Portland Oregon

“We want to create awareness for the issue of mass incarceration all the while focusing on one person at a time to make people feel human again. With our exchange we challenge our expectations of a foreign country and our expectations of prison and create artistic opportunity for both artists at CRCI and the photographers abroad,” say Schüttler and Thakore.

——–

If you’d like to collaborate, email answerswithoutwords@gmail.com with the following information:

– your name.

– the country you are currently located at and from which you’d participate.

– examples of your photographic work (a website URL or 5-10 images).

The prisoners in the Free Mind Collective will send 5 to 10 questions.

Time is ticking though! You have 4 weeks. All materials must be sent to Answers Without Words by March 31st.

——–

Answers Without Words is a project done in conjunction with the Portland State University MFA in Art + Social Practice and funded by the Precipice Fund, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the Calligram Foundation.