You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘California’ tag.

OPENING REMARKS

I’ve stated it before but not often or forcefully enough: The LGBTQ community nurtures many of the most effective and motivating voices in the fight for prison abolition. LGBTQ people are frequently subject to the harshest and most dehumanizing treatment at the hands of the prison system. It is from this position that activists and formerly incarcerated individuals have mobilized against the prison industrial complex.

In the news, it is the circumstances of transgender people in prison that are most often described and decried. For clear reasons: imagine being held within a male facility when you identify as female. Or in a female facility when you identify as male. Read up on the situations of Marius Mason and Vanessa Gibson. In Pittsburgh, Jules Williams, a transgender woman suffered sexual and physical assault and harassment multiple times while detained at the Allegheny County Jail, a mens facility.

Very, very few prison or jail systems place transgender folx in facilities where they are free of victimization and predation. During her three years of incarceration in the Georgia Department of Corrections, Ashley Diamond was repeatedly assaulted, once after GDC officials placed her in a cell with a known sex offender. Diamond took the radical step to appeal directly to the public via “illegal” YouTube videos from her prison cell made on a contraband smartphone.

Diamond won freedom following a lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the conclusion was that the GDC didn’t want to deal with the expense and supposed inconvenience of providing the hormone treatments she’d been on for 17 years prior to her imprisonment. Similarly, in California, Michelle-Lael Norsworthy was freed unexpectedly when her lawsuit for access to healthcare threatened the CDCR with huge medical bills. Shiloh Quine won the right for sexual reassignment surgery, but hers, all too unfortunately, was an exceptional case.

(For an instructive overview of the experience of female trans prisoners, read Kristin Schreier Lyseggen’s book Women of San Quentin: Soul Murder of Transgender Women in Male Prisons which details the stories of nine women, including Janetta Johnson, Tanesh Watson-Nutall, Daniella Tavake, Diamond, Quine and others.)

While transgender people are winning more and more hard-fought recognition in open society, prisons occupy the other end of the spectrum—closed, rigid systems unable to safely house the majority of prisoners and certainly unprepared and, more often, patently unwilling to recognize prisoners with gender dysphoria and their specific needs. (Trans issues are at the forefront in the military again. The regressive and punitive White House is banning transgender personnel from service. Unsurprisingly, DJ Pee-Tape is largely at odds with much of the military command.) Historically, the marginalization and criminalisation of LGBTQ people has funneled them into the criminal justice system, too. That point needs to be made.

Transgender prisoners are just one group within the LGBTQ community. Lesbians and gays face daily vilification within the criminal justice system. The tactics for resistance of different groups within the LGBTQ community necessarily vary in specific ways, but the enemy is common.

In a push back against the homophobia and transphobia embedded within the criminal justice system we should look to leaders such as CeCe McDonald, Dean Spade and Reina Gossett. Their intersectional critique of policing and prisons connects the dots between discriminations of all types. Prejudice and inequality exist within our society; certain groups, including LGBTQ and particularly LGBTQ persons of color, are valued less than others. The root causes for racism, sexism, imperialism, militarism are the same, and those root causes not only emerge out of capitalism but are, in many ways, its foundations. The complete abandonment of LGBTQ persons’ needs in prisons brings into sharp focus the fact that the systems, and our society from which they grow, deem this group more disposable than others.

“Prison abolition means no one is disposable,” says Reina Gossett. Exile is not a solution to the shortcomings of a society; exile allows wider discrimination to perpetuate.

“We should not model what the state’s logic is about who is disposable,” Gossett continues. “Challenging and dismantling structures of violence. [We need] relationships modeled on a different logic, not on the logic of white, heteronormative hegemony.”

Seen through a queer lens, the violence of the prison industrial complex is laid bare. Prisons are sites of waste and sites of survival; sites into which those outside the dominant norm are discarded. True to capitalist, carceral logic, the only economic benefits prisons bring about are for the state, law enforcement unions, corporations and craven politicians. We, the taxpayers, hand over this wealth at the expense of the lives and livelihoods of all those locked up. In the modern U.S., prisons are not about “time out” or rehabilitation; they’re about control in order to instill order. Prisons crush humanity and they assault diversity.

Prison abolition is about identifying structures of violence and working against them; about prefiguring a better world in which you want to live. In reviewing the book Queer (In)Justice (Ed. Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock), journalist and activist Vikki Law notes the authors’ contention that “deep-seated prejudices and fears of queer people cannot be dismantled via hate crime legislation.” Social attitudes are the strongest underpinning to a just society, not the latter-stage adjudications of the law.

“The authors say,” continues Law, “that ‘many of the individuals who engage in such violence are encouraged to do so by mainstream society through promotion of laws, practices, generally accepted prejudices, and religious views,’ and they note that homophobic and transphobic violence generally increases during highly visible, right-wing political attacks.

(For an introduction to community organising toward abolition, read James Kilgore’s recent piece Let’s Imagine a National Organizing Effort to Challenge Mass Incarceration.)

Prison abolition is about pushing back on all the structures that manifest the suspicion, dismissal and abuse of people who counter the white patriarchal status quo. That includes visual structures. That includes, as Critical Resistance states, “the creation of mass media images that keep alive stereotypes of people of color, poor people, queer people, immigrants, youth, and other oppressed communities as criminal, delinquent, or deviant.”

That is why Lorenzo Triburgo’s project Policing Gender is so important. Triburgo, a trans man, is not only advocates for the larger LGBTQ rights at stake, but also makes images that bring the weight of photographic history and analysis of images’ power to bear on his decision-making and design. His is a queer perspective. Policing Gender is enigmatic and beautiful and devastating. Triburgo’s personless portraits point us past what the images are in-and-of-themselves and toward a critique of what images have done in the past in service of, and to damage, LGBTQ-identified people.

I can make no apology for the length of these introductory remarks, because these photographs are built upon years of Triburgo’s conscientious thought, and on decades of queer activism by countless others. Context is important. From here, I’ll let Triburgo himself explain the conceptual underpinnings of Policing Gender and just add how grateful I am for our extended conversation. Scroll down for our Q&A.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): We first met in Portland around 2012 or 13. We published a conversation in 2014. At that time you’d just picked up research for a photographic project on the topic of mass incarceration. You explained then that you’d wanted to do portraits of families, but the warden explained that the visiting room had a program for such portraits. The idea was shelved for a while, as you made Transportraits, but you knew you’d come back to it. Family portraits are very different to these curtains and aerial landscapes. How did you get from there to here?

Lorenzo Triburgo (LT): When I began Policing Gender I collaborated with the queer prison abolition organizations Black & Pink and Beyond These Walls to become pen pals with over 30 LGBTQ-identified prisoners. I wrote and talked with my pen pals for months and months before deciding on what the project would entail visually.

Keep in mind that I also worked to gain access to various prisons and jails. I was doing my *photographer’s due diligence*. However, after getting inside, I thought, “F##k that. I’m not going to create photographs that could potentially strengthen the association between queer people and criminality.”

I kept obsessively thinking, “I want to make portraits, but not portraits. Portraits, but not portraits.” I was wracking my brain. The reasons were twofold.

First – ethically, as a queer person, feminist, and artist I am particularly sensitive to issues of representation and exploitation. I could have made the portraits but, to what end? How radical can a straightforward portrait really be? Would portraits of queer prisoners bring anything to the world besides an opportunity for viewers to gawp or sate their curiosity and voyeurism?

One of the hellish qualities of prison is the complete lack of privacy. Random administrators, politicians, teachers and students might make visits to a prison and get led on “tours” where they can peer-in on any prisoner through a tiny window and just watch. Did I want to replicate that experience with my camera lens? No.

Furthermore, how would I know for sure that I was getting informed consent from participants? In what world would our exchange be equal? Even more importantly, in what world would the exchange between any prisoner and viewer be equal?!

Secondly, conceptually, I felt my project demanded a complex approach that would embody the depth, pervasiveness, scale and abuses of the U.S. prison system. It needed to be more than a single-layered visual representation; more than a straightforward portrait.

LT: I started to think about making portraits with no figures.

What if instead of putting my incarcerated pen-pals on display, I go a quieter more contemplative route and conjure a sense of absence? The next step was to figure out what the figureless portraits would look like. I recalled a lecture by Cathy Opie where she cited renaissance portraitist Hans Holbein as a major influence. Holbein and Opie use fabric as a symbol of wealth, power and beauty.

PP: But to different ends.

LT: Yes. Opie appropriates formal aesthetics in order to queer the photographic portrait. I saw that I could use fabric and create connotations of portraiture and, for some of us, make a nod to queering the portrait through the use of form. It felt I’d found an answer to the inevitable imbalance of power between prisoner and viewer that I wanted to avoid perpetuating. Figureless portraits point toward this thorny ethical ground.

While thinking all this through, I was discussing my ideas with activists and researchers including Dr. Susan Starr Sered, co-author of Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility. Dr. Sered and I had a conversation that solidified my decisions.

PP: On your work’s figurelessness, an editor with whom I spoke recently referred to your work as “withdrawn”. It wasn’t a criticism per se, but I wonder about your reaction to that assessment?

LT: My pen-pals are trans and queer, and young and old, and out and not out, and coming out for the first time, and helping others come out for the first time all behind bars. I wrote and talked with them for months and months before deciding on what the project would entail visually. The decision to exclude people in the images is not ONLY about theoretical distancing from prisons and a challenge to photographic voyeurism. It’s also about anonymity for safety reasons and my pen-pals not always being able to come out without endangering their safety, and about recognizing that prisoners are a protected subgroup and not always able to give knowledgeable consent.

The figurelessness is about the absence of 2.3 million prisoners from society.

It’s difficult to communicate absence through photography but that was a risk I wanted to take. I believe we are at a stage when absence can be just as powerful as presence because there is so much photographic presence.

The work isn’t withdrawn. It’s emotional. It’s meditative. It’s quiet. I’m asking the viewer to take a minute and reflect: on their position in the world, on their assumption that they get to “see” whatever they want to see, and on the people who are missing from our society.

The lighting in these pieces was a meditative process for me. It was a way for me to process what I was learning about from my pen-pals. It’s not a vapid conceptual piece in reaction to the prison system. Each fabric represents a set of circumstances that was told to me by my pen-pals and is therefore named after them — each is a combination of their names.

PP: And what about the aerial shots?

The aerial images are about surveillance. The construct of imprisonment. The natural contained. Creating these was also an emotional process. I was in the hot air balloon …

PP: Wait! You were in a hot air balloon?!

LT: Ha! Yes. I photographed from a hot air balloon.

Balloons were an early method used by photography in the service of surveillance. During the U.S. Civil War, hot air balloons were used to create the first aerial reconnaissance images. I was looking for a way to undermine the idea of surveillance and to portray a grandiose notion of the ‘natural’. But once I was up there I couldn’t escape the feeling of my social position, the feeling of sadness and anger and unearned privilege and wishing that I could bring my pen-pals up in the air with me. The aerial photographs ultimately reflect these emotions and, metaphorically, the inescapable presence of surveillance.

All of my emotional experiences have a direct correlation to my conceptual interests in photography. It’s how I process the world.

I think about portraiture all the time. I feel the experiences of my various identities and ways I present myself to the world and the way I’m “seen”. I see oppression based on identities and I process that by creating photographs, and in the case of Policing Gender, audio art, too.

Photography is a way for me to make sense of the world and for me to present ideas to the world. These ideas are emotional as much as they are political and theoretical because I feel like I live them. I’ve had someone else’s camera pointed at me because I seemed “interesting” and it feels like crud.

PP: How are LGBTQ identified people affected by the prison industrial complex?

LT: Right now there are 1.6 million youth facing houselessness in the U.S. We know that 46% of these youth are LGBTQ identified. Add to that, cities across the U.S. are increasingly passing laws that ostensibly make it illegal to be homeless. Over the last ten years, there’s been a steady increase in the number of cities that have made it is illegal to lay down, sleep, or even sit in public and (in cities like Houston) to share or give food to people. Once queer youth are arrested and detained they are more likely to be sentenced to jail time and serve longer sentences than their non-LGBTQ peers.

We also know that people who have been arrested have a higher chance of returning to jail or prison. So, these youth grow up to be LGBTQ identified adults with a much higher chance of spending time in U.S. prisons. This is especially true for people of color, youth, immigrants, differently abled, and poor people. So, are queer people in prison because they are queer? If we look at the systemic level, rather than a matter of individual choices, the answer is yes.

PP: Which LGBTQ-focused individuals and organisations are working specifically and effectively against mass incarceration?

LT: The book Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex edited by Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith is an invaluable resource for just this question. It was published by AK Press soon after I began Policing Gender; this book came to me at exactly the right moment and is an invaluable resource.

Captive Genders includes first person narratives, research, and political analysis with an emphasis on writing from current and former prisoners.

I personally worked most with Black & Pink and Beyond These Walls.

Black & Pink is a grassroots organization that has been working in support of LGBTQ prisoners and towards prison abolition with nationwide chapters for over ten years. Their website is also an incredible resource. Beyond These Walls is Portland-based and is another grassroots prison abolition effort with a focus on supporting queer prisoners.

In the intro of Captive Genders, Stanley writes, “It is also important to highlight that women, trans, and queer people (specifically of color) have done much, if not most, of the anti-PIC organizing in the United States.”

Case in point: Miss Major Griffin-Gracy has been an activist for over 40 years and was the first Staff Organizer at The Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP). TGIJP is based in California and began as a legal project with leadership by formerly incarcerated trans women of color. Miss Major is recently retired from TGIJP but continues to be a badass inspiration to us all. (I recently saw her on the panel for the release of the book Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility at the New Museum).

The Sylvia Rivera Law Project, formed by civil rights activist and attorney Dean Spade in 2002, must also be mentioned here. SRLP provides legal aid to low-income trans, gender non-conforming, and intersex people and “is a collective organization founded on understanding that gender self-determination is inextricably intertwined with racial, social, and economic justice.”

PP: You once expressed an interest in photographing prison guards/correctional officers. Do you still?

LT: No, but I think someone should. The abuse that prisoners face at the hands of correctional officers is abhorrent — and — it is crucial to recognize that the job of correctional officer is basically designed to produce and enable a monstrous abuse of power. If we are to understand the prison industrial complex for what it is – an entire system of oppression upheld in part by the narrative that people of color, poor people, and queer people are dangerous – we also need to recognize systemic/social/economic conditions that lead someone to become an officer and the mental trauma associated with this job.

According to one study (Stack, S.J. & Tsoudis, O. Archives of Suicide Research, 1997) the risk of suicide for correctional officers is 39% higher than their peers in other professions and other studies show increased PTSD, divorce, and substance abuse. (See: Denhof, Michael D., Ph.D and Caterina G. Spinaris, Ph.D., Desert Waters Correctional Outreach, 2013.)

The effects of unchecked power, a career culture that encourages and rewards racism, homophobia, sexism, and xenophobia and corruption that goes all the way up the chain are traumatic. Hello Stanford Prison Experiment!?!

To go out on a limb, and to quote Michelle Alexander , I think of the job of the correctional officer as one manifestation of the many “efforts by the wealthy elite to use race as a wedge. To pit poor whites against poor people of color for the benefit of the ruling elite.”

Alexander continues, “Many people don’t realize that even slavery as an institution—the emergence of an all-Black system of slavery—was to a large extent the result of plantation owners deliberately trying to pit poor whites against poor Blacks. They created an all-Black system of slavery that didn’t benefit whites by much, but at least whites were persuaded that they weren’t slaves and thus were inherently superior to Black folks.” (‘The Struggle for Racial Justice Has a Long Way To Go’, The International Socialist Review, Issue #84, 2012.)

Keep in mind that people who take these jobs are predominantly working class, often with no other viable option for work because other industries have been (systematically) replaced by the prison industry in towns across the U.S. I feel myself holding my breath and my heart racing in anger as I say this.

PP: You have said repeatedly and in public that you’ll respond to any LGBTQ prisoner who writes to you. Kudos to you. That’s a serious commitment. It must also be quite the emotional experience—good and bad. Tell us about letter writing.

LT: So much here. I don’t know where to start exactly. In previous interviews I ducked the question out of fear of sounding schmaltzy, because it is super emotional and I don’t want to come off sounding all “we are the world” or like, neoliberal humanist or something.

That said, it has been fucking incredible.

There’s something astonishing about getting to know someone slowly, over time, through written word. How often do we have the opportunity to get to know someone completely from scratch? With no photo to go by, no list of basic likes or dislikes, not knowing their preferred name or gender, or where they are from. I got to know my pen-pals’ handwriting and that is a specific intimacy unlike any other type of exchange.

I never ask my pen-pals why they are in prison. Instead, I ask about what they think are the most pressing needs of LGBTQ prisoners and what they think an artist can do. Very often the response is that a way to share their stories and their truth would be a huge help. In the audio for Policing Gender you hear one of my pen pals say, “At least out there you’ve got cell phones to record this stuff [abuse by officers], in here it’s complete secrecy.”

I’m not interested in “giving voice”—my pen-pals all have voices! But I am interested in giving their voices a platform outside prison.

By not asking about why they were in prison I aim to, at minimum, create a space for my pen-pals to talk to someone who didn’t see them first as a criminal and second as a person. I challenged myself, to be honest, to allow myself to be vulnerable, to share my thoughts, and to allow our conversations to develop without pre-judgements.

We talked about the prison system of course, but we also shared our coming out stories, what it was like during high school, whether our family was religious, our siblings, our parents, their kids. Some of my pen-pals were younger than me and grew up in the “Glee era” while others were baby boomers and couldn’t imagine being accepted as queer when they were younger. One of my pen-pals was really into Shakespeare. I am not. And we would joke about that.

I love getting to know people and their stories—so it was just wonderful in that regard. I would also simply Google information and send it upon request. It is so easy to take our access to information for granted! I would send variations on photo assignments I give my college students, making them into creative writing or drawing prompts.

There was one person with whom I lost contact and that was devastating. The last I heard of her she had been raped, then left in solitary confinement for 24 hours, then finally taken to a hospital —four hours away—given antibiotics on an empty stomach, then driven back to the prison while handcuffed in the back of a van. If you’ve ever taken antibiotics you know that they are nauseating in the best of circumstances. I don’t like to talk about stories like this too much. They are important but I also don’t want to sensationalize my pen-pals’ suffering.

I wrote with over 30 people on a monthly basis for almost two years. I still write with a small number of people and I continue to pair every incarcerated pen-pal who gets in touch with me with someone to write with on the outside. So far I’ve connected about 40 people with new pen-pals.

PP: I know you’ve designed a course on gender and photo at SVA, so if it’s not revealing any too much info, can you give us a few important titles and articles from the course reading list?

LT: My course at SVA is a studio/portfolio course where we incorporate queer studies concepts in the development and critique of projects. (The class is offered online through SVA Continuing Education. Therefore, anyone interested in exploring these ideas in their artworks can register). I also developed a graduate level seminar that I teach online for Oregon State University with a focus on representations of gender and sexuality from a feminist perspective.

Here’s a greatest hits list of texts:

- Barthes, Roland. “Rhetoric of the Image.” Image, Music, Text. Ed. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 32-51.

- Blessing, Jennifer. “Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography.” Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1997. 7-38, 67-119.

- Halberstam, Jack. “Technotopias: Representing Transgender Bodies in Contemporary Art.” In a Queer Time and Place. New York and London: New York University Press, 2005. 97-124.

- Jhally, Sut. “Image-Based Culture: Advertising and Popular Culture.” Gender, Race and Class in Media: A Critical Reader. 3rd ed. Eds. Gail Dines, Jean M. (McMahon) Humez. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2011. 199-204.

- Lorber, Judith. “Night to His Day: The Social Construction of Gender.” Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994. 13-36.

- Mercer, Kobena. “Reading racial fetishism: the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe.” Visual Culture: The Reader. Ed. Jessica Evans, Stuart Hall. London: Sage Publications, 1999. 435-447.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Visual and Other Pleasures (Language, Discourse, Society). 2nd ed. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 14-30.

- Rosler, Martha. “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography.)” The Photography Reader. Ed. Liz Wells. London: Routledge, 2003. 261-274.

- Sullivan, Nikki. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. New York: NYU Press, 2003.

- West, Candace, and Don H Zimmerman. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society Vol. 1, No. 2. (1987): 125-151.

LT: I also want to give a shout out to these texts that strongly shaped my aesthetic and ethical decisions in Policing Gender:

- The Subversive Imagination: Artists, Society, and Responsibility, Carol Becker.

- Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 2011. Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

- Queer (In) Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States, Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock.

- Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith.

- Are Prisons Obsolete, Angela Davis.

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander.

- Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility, Susan Starr Sered and Maureen Norton-Hawk.

- Punishment and Social Structure, Georg Rusche and Otto Kirchheimer.

PP: Wow, thank you, so generous. So many new texts for me. Have you a resource list of organizations working in solidarity with LGBTQ prisoners?

LT: Absolutely, these are organizations as listed in the book Captive Genders:

All Of Us Or None

1540 Market Street Suite 490, San Francisco, CA 94102

415.255.7036 [ext 308, 315, 311, 312]

info@allofusornone.org

http://www.allofusornone.org

ACT UP Philadelphia

P.O. Box 22439, Land Title Station, Philadelphia, PA 19110-2439

actupp@critpath.org

http://www.actupphilly.org

Audre Lorde Project

85 South Oxford St., Brooklyn, NY 11217

718.596.0342

http://www.alp.org

Bent Bars Project

P.O. Box 66754, London, WC1A 9BF, United Kingdom

bent.bars.project@gmail.com

http://www.bentbarsproject.org/

Black and Pink<

c/o Community Church of Boston, 545 Boylston St., Boston, MA 02116

http://www.blackandpink.org

BreakOUT!<

1600 Oretha C. Haley Blvd., New Orleans, LA 70113

http://www.jpla.org

Critical Resistance

1904 Franklin St, Suite 504, Oakland, CA 94612

510.444.0484

http://www.criticalresistance.org

FIERCE!

437 W. 16th St, Lower Level, New York, NY 10001

646.336.6789

http://www.fiercenyc.org

generationFIVE

P.O. Box 1715, Oakland, CA 94604

510.251.8552

http://www.generationfive.org

Gay Shame

San Francisco, CA

gayshamesf@yahoo.com

http://www.gayshamesf.org

Hearts On A Wire

(for folks incarcerated in PA)

PO Box 36831, Philadelphia, PA 19107

heartsonawire@gmail.com

INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence

P.O. Box 226, Redmond, WA 98073

484.932.3166

http://www.incite-national.org

Justice Now

1322 Webster Street, Suite 210, Oakland, CA 94612

510.839.7654

http://www.jnow.org

LAGAI—Queer Insurrection

lagai_qi@yahoo.com

http://www.lagai.org

Prison Activist Resource Center

PO Box 70447, Oakland, CA 94612

510.893.4648

http://www.prisonactivist.org

Prisoner Correspondence Project

http://www.prisonercorrespondenceproject.com

Prisoner’s Justice Action Committee

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

pjac_committee@yahoo.com

http://www.pjac.org

Sylvia Rivera Law Project

322 8th Ave, 3rd Floor, New York, NY 10001

212.337.8550

http://www.srlp.org

Tranzmission Prison Project

P.O. 1874, Asheville, NC 28802

tranzmissionprisonproject@gmail.com

Transgender, Gender Variant, and Intersex Justice Project

342 9th St., Suite 202B, San Francisco, CA 94103

415.252.1444

http://www.tgijp.org

Write to Win Collective

2040 N. Milwaukee Ave., Chicago, IL 60647

writetowincollective@gmail.com

http://www.writetowin.wordpress.com

PP: Brilliant. Again, thanks so much.

LT: Thank you, Pete.

This week, Mimi Plumb kindly let me write about her series What Is Remembered which shows the clearing of orchards and farms for subdivisions between 1972 and 1975, in her (then) hometown of Walnut Creek. She photographed the alienated kids who reminded her of her younger self. I first met Mimi in 2014. It feels like this article has been a long time coming. I had wrote about 500 words. I wish I had 500 pages.

I adore Mimi. I posted about her series Pictures From The Valley, when her images were used in an initiative to find farmworkers involved in California labor organizing, and then to secure their oral histories.

What Is Remembered is evocative stuff fusing memory, generational differences, consumerism, fear, innocence and our place in the world–that is all to say, our responsibility to the world.

To quote:

After a career teaching photography, only recently has Plumb returned to her archive. Nostalgia, partly, accounts for the current popularity of Plumb’s work. But, frankly, it is only now that people have the stomach for it. While her college instructors at the time loved the work, it was too unadorned and too uncomfortable for many others to appreciate.

“The raw dirt yards and treeless streets, model homes expanding exponentially, with imperceptible variation. A lot of it’s pretty dark and some of it is pessimistic.”

Plumb never felt comfortable among the cul-de-sacs and manicured yards. She rarely had the words for what she was experiencing … until she discovered photography in high school.

In 1971, the two lane road to the city became four lanes. Aged 17, Plumb left for San Francisco. The bland atmosphere of the suburbs stood in stark contrast, says Plumb, to the cultural and violent upheavals taking place across the country — the shooting of John F Kennedy, the ongoing threat of nuclear war, the civil rights movement, and the anti-war movement.

“Suburbia felt like something of a purgatory to me,” she explains. “It was intellectually hard; you couldn’t really talk about what was going on in the world.”

“I watched the rolling hills and valleys mushroom with tract homes,” says Plumb. “To me and my teenage friends, they were the blandest, saddest homes in the world.”

More: Photos of growing up in the Bay Area suburbs tell a story of innocence and disaffection

Angelo on his cell bunk

–

Marc and Brett of Temporary Services shared a tribute to Angelo this week. They collaborated together on Prisoners’ Inventions, and although I never knew (very few people did) Angelo (not his real name, his artist name), I wanted to mark his passing here on the blog.

Prisoners’ Inventions started as a collection of more than one hundred annotated illustrations of inventions that Angelo made, saw, or heard about while incarcerated. From homemade sex dolls, salt & pepper shakers to chess sets, from privacy curtains and radios to condoms and water heaters–all “attempts to fill needs that the restrictive environment of the prison tries to suppress,” writes Temporary Services.

Battery Cigarette Lighter

It seems so long since Prisoners’ Inventions landed on my radar and even then, I was years late to the project. Someone showed me a copy of the book in 2011. But the first edition of the book was published in 2003, and new editions followed. In 2003 and 2004, Prisoners’ Inventions was presented as an exhibition at MassMOCA, complete with a full replica of Angelo’s cell, and later travelled to numerous venues. Around that time, international press blew up around the originality and the cheekiness of it all. This American Life did a bit.

Prisoners’ Inventions set a standard in many ways for artists and incarcerated individuals working in tandem–the way Angelo insisted on anonymity; the way Temporary Services held the space; the way together they let the illustrations do the work; the manner in which they (despite the barriers and censorship) communicated transparently and studiously; the way they fired public imagination with recognitions of human spirit, ingenuity and agency among a prison population so frequently vilified; the way Angelo and Temporary Services resisted any over-politicization of the project; I could go on and on.

Coat Hanger

Too often we think of art as being things not doings, as objects not relationships or as things that can exist on a shelf instead of in our hearts and minds. While Angelo and Temporary Services made objects based upon the drawings, objects were never the goal. Prisoners’ Inventions existed to demonstrate the innate creativity we all hold and also the potential in even simple written (and drawn) correspondence. It was about meaningful relation and understanding of people in very different circumstances. Temporary Services call Angelo their greatest ever collaborator, which is a huge statement from an art collective known for it communal underpinnings.

“Angelo’s writings and drawings about the creativity he observed in prison collapsed the distinctions between art and everyday survival,” said Temporary Services. “He transformed our thinking in ways that have influenced everything we’ve done since.”

In truth, Prisoners’ Inventions has influenced many an artist’s thinking and methodology since.

Steamer Cooker

A common problem with artwork that deals (even tangentially) with the issue of mass incarceration, or with prisoners directly as art makers, is that the art can often fail to break down the inherent power imbalance; that the prisoner is packaged by the outsider for outside public consumption. Furthermore, some art and language can’t help but fall into patronizing stereotypes about how the artist is helping the prisoner … and that the prisoner is helpless. Prisoners’ Inventions never trivialised, infantilized or boxed Angelo’s work. Nor did Temporary Services and Angelo ever try to argue it was something it was not which I think is a reflection of their trust, equity and confidence.

“People seem willing to accept the inventions of prisoners as creative objects that merit our attention and thought without us having to force them into goofy critical constructs like *Outsider Art*,” said Temporary Services in the book Prisoners’ Inventions: Three Dialogues (PDF). “These objects don’t need critical help to become interesting. New terminology does not need to be invented to create a niche market or new genre for a stick of melted-together toothbrushes and bits of metal that can be used to make apple strudel in a prison cell.”

If you can take the time to read Prisoners’ Inventions: Three Dialogues, please do. It lays out the origins, conversations, adaptations and logistics of the multi-year project. It elaborates on subtle concepts. It shows that good art rests on a solid idea and no-bullshit presentation of the idea. The way Prisoners’ Inventions moved through cultural space, both IRL (galleries, vitrines, fabricators’ hands) and virtual (image, video, online featurettes, audience mind and assumption) and through real economic systems is fascinating. The way Temporary Services discuss the negotiation of these things in relation to their promises and shared goals with Angelo is grounding and, I think, instructive.

Stinger (Immersion Heater)

Marc and Brett explain that since Angelo’s release in 2014 he lived quietly in Los Angeles, keeping to himself, catching up on TV and films he missed while locked up for 20 years. They also mention that Angelo had to wait until release before he could see and hold a book of his drawings; the prison administration banned any copies entering the prison because (and you can’t help but laugh) the drawings would show Angelo how to jury-rig objects and homebrew solutions!

The threat was imagined and the logic flawed, of course, but this brings me to a final point. Prisoners’ Inventions did not advocate for Angelo. Never did he and Temporary Services get involved in discussions about his case or legal matters. Not once did the work threaten prison security or reveal anything unknown to nearly every prisoner locked up in America. Opportunities for meaningful, collaborative and non-combative artwork within the prison industrial complex are few and far between. I think it is vital that we recognize art and activity that amplifies the existence of some without ignoring that of others; that we seek projects that lift us all. Mass incarceration is a depressing thing, but there are moments of humor, surprise quirk and enlightenment. Be ready for them! Prisoners’ Inventions succeeded in closing the gap between us and them without forcefully or uncomfortably insisting on the defining terms of us and them. Prisoners’ Inventions occupied a rarified space and we do well to learn from it.

I’ll close with a story about when, during a cell search, guards found photos of the full replica of Angelo’s cell.

“Stunned and angered that an inmate had somehow acquired photos of his own cell, the guard demanded information on how he got the pictures. When Angelo pointed out the fabricators’ subtle discrepancies in the cell recreation and explained a little about the exhibition, the guard’s anger quickly turned to wonder and amusement.”

Angelo, you mined your memory, you humbly shared your knowledge, you made drawings that confounded expectations and shifted minds. You never wanted fame or fortune. You made a thing that will last. RIP.

Screengrab from the Los Angeles Times’ interactive feature Should California execute these 749 death row inmates?

–

Pursuant to recent posts about California’s potential bellwether ballot vote to repeal the death penalty and about the grouping portraits of men executed by the state of Texas, here’s an important interactive feature from the Los Angeles Times on the 749 prisoners on California’s death row: Should California execute these 749 death row inmates?

Thirteen prisoners have been executed in California since 1978. A tiny figure in contrast to the 728 men and 21 women currently on its death row. With 749 prisoners, California has by far the largest number of capital convictions of any state.

The Los Angeles Times provides a close look at each condemned prisoner and the crimes that put them on death row. Crucially, for me, they’re using photographs (mugshots) of each as the entry point into the cases. This is a deliberate attempt to put a face to the statistics. I wouldn’t say it is humanizing, but it does hammer home the individuality of each prisoner. Even with each prisoner represented by only a small thumbnail, it is a long, long scroll through the portraits. The effect is chilling. There are a lot of lives at stake and they are, effectively, in our hands. The title Should California execute these 749 death row inmates? is a direct challenge to each of us.

As I outlined earlier this week, California has two competing initiatives on its ballot, Prop 66 would expedite executions whereas Prop 62 would repeal the death penalty replacing it with Life Without Parole (LWOP). For me, Prop 62 is not an ideal solution as LWOP is just another form of state-delivered death, yet Prop 62 could be a step in the right direction if future campaigning against LWOP succeeds. And it does get California out of the business of killing its residents.

In light of this vitriolic, shambolic and bilious Presidential campaign, I guess I’m also relieved to see images that are related to criminal justice being used responsibly and without spin. Of course, that’s what we should expect from journalism. The tone of this news treatment of mugshots runs counter corporate circulation of mugshots for personal, financial gain, and the abuse of people in mugshots by public officials. (Thankfully, Maricopa County in Arizona has ceased its ‘Mugshot Of The Day’ public humiliation exercise).

What do you think about the LA Times’ use of these photographs to inform public debate? Do they help California voters decide?

In spite of the fact I am currently without home, I am deeply connected to the politics of California. When I first came to study in the US, it was in California. When I first came to live in the States, it was in California. Over the past 3 years, I’ve lived in California again. As I travel the States currently, it is with a California drivers license.

More than any of these factors though, California is important because it is a bellwether state. When policy–progressive or otherwise–is enacted in the Golden State, it is often followed by similar policy in other states. Three Strikes Laws are a prime example. One of the first to pass Three Strikes into state law (in 1994), California was also the first to offer voters the chance to repeal many aspects of the overly-punitive sentencing. Which they did in 2012 with Prop 36.

PROPS 62 AND 66

The main issue on this years ballot is the death penalty. There are two ballots that are philosophically and procedurally opposed to one another.

Prop 62 will outlaw the death penalty. Vote YES.

Prop 66 will throw money at the broken system by speeding up the legal process, which might bring about some successful appeals but will more likely send men and women to the chamber at unprecedented rates. Vote NO.

749 people are currently on death row in California. The liberally-minded state is reluctant to execute people and this has resulted in those sentenced to death to swell the cell tiers of inadequate facilities and to be held in a permanent stasis. Of the 13 people executed since 1979, the average stay was more than 17 years on death row. I would assume that the average stay of those currently on death row is slightly less than that. (For a brief history of the death penalty in California, I recommend Judge Arthur L. Alarcon’s Remedies For California’s Death Row Deadlock.)

The choice is clear. The state should not be involved in killing citizens. Vote YES on 62. This is a position held by the widow of a police officer whose murderer is the last person in the state to be sentenced to death.

At this juncture, I’d like to point out the bind in which Californian activists and prisoners find themselves over Prop 62.

If the death penalty is repealed, all those on death row will have their sentences changed to Life Without Parole (LWOP). Among activists, LWOP is referred to as Death By Incarceration. This statement, from California Coalition for Women Prisoners, made by women currently serving LWOP sentences is the most nuanced position I’ve encountered on the 2016 ballot initiatives. I quote at length:

We believe LWOP is racist, classist and ableist, condemns many innocent people to a slow living death, and neither deters violence nor promotes rehabilitation. The majority of people serving LWOP in California’s women’s prisons are survivors of abuse and were sentenced to LWOP as aiders and abettors of their abuser’s acts. We believe that LWOP relies on the intersections of racial terror and gendered violence.

For voters who oppose all forms of death sentences including LWOP, the choice between an initiative that replaces one form of death with another (Prop 62) and an initiative that speeds up executions (Prop 66) is hardly a choice at all. It is morally compromising to vote for Prop 62, which further criminalizes and demonizes our loved ones and creates a false hierarchy between forms of state-sanctioned death. However, we recognize that a decision to vote against Prop 62 is complicated by fear that Prop 66 will win. Ending the death penalty in California could be a powerful symbol for the rest of the country and represent a growing awareness of the injustices and inhumanity of incarceration and the criminal legal system as a whole. Every person who votes will need to make a difficult decision about two very problematic propositions.

We believe that both the death penalty and LWOP should be recognized as unjust and eliminated. One of our LWOP partners in prison, Amber states: “To reassure people that LWOP is a better alternative to death is misleading.” Rather than facing executions, people with LWOP will die a slow death in prison while experiencing institutional discrimination. People with LWOP cannot participate in rehabilitative programs, cannot work jobs that pay more than 8 cents an hour, and will never be reviewed by the parole board. We agree with the Vision for Black Lives policy goal to abolish the death penalty and we believe that true abolition of the death penalty includes abolishing LWOP and all sentencing that deprive people of hope.

When the death penalty was temporarily banned from 1972 to 1976 by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling all people then on death row had their sentences overturned or converted to life [with possibility of parole]. Many of these people successfully paroled and are now contributing to their communities.

That said, Prop 62 doesn’t discount the possibility of future political action against LWOP and its ultimate repeal. And I hope that happens. Therefore, I still say Vote YES on 62

PROP 57

Also on the ballot is a measure, Prop 57 to reduce sentencing for non-violent crimes, put more discretion in the hands of judges for sentencing, and limit the trying of juveniles as adults. No brainer: Vote YES.

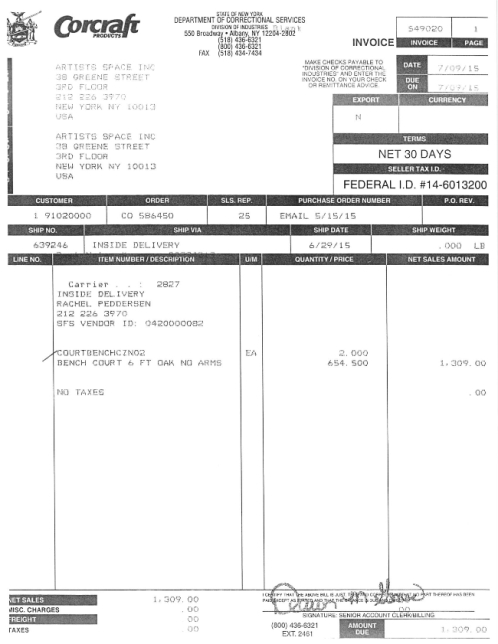

Cameron Rowland, “New York State Unified Court System” (2016), oak wood, distributed by Corcraft, 165 x 57.5 x 36 inches, rental at cost. Courtrooms throughout New York State use benches built by prisoners in Green Haven Correctional Facility. The court reproduces itself materially through the labor of those it sentences. (photo by Adam Reich, courtesy the artist and ESSEX STREET, New York)

You may have sat in the chairs, or slept on the pillows, or worn the smocks. What am I talking about? You may have used goods made by prison labour. You or your kids, depending what state you’re in, may have eaten school meals made by prisoners.

Wellington boots, uniforms, mattresses, furniture, binders, paper-goods, forms, flagpoles, hardware, utensils, even cookies … the list of goods made by prison industries is long. CALPIA (California Prison Industries Authority) in California and Corcraft in New York State are just two government agencies making high-quality goods while paying low-quality wages.

Prisoners working for CALPIA earn between 30 and 90 cents per hour (the higher end is rare) and then about 50% is taken out for taxes, charges and restitution. Supporters of these multimillion dollar agencies say it they provide valuable jobs training for prisoners. Opponents say it’s slave labor. Of course, you’re opinion will be swayed by whether you think prisons and jails are a net benefit or a net cost for society.

For prison abolitionists these state-insider agencies are second only in evil to the private prison companies. Why? Because they execute the quieter but some of the more pernicious maneuvering within capitalism. They devalue labor and devalue human beings. In California, those that defend CALPIA point out CALPIA only sells to other state bodies, but a market is a market and who the buyer is doesn’t change the work, wages or conditions for prisoners. In fact, most state-run prison industries don’t sell beyond state agencies is because they’d destroy many “free” markets simply by undercutting them on price–so great is the savings on wages. Look at those benches above; the joinery on those is out of this world. A steal at $654.50 (see below).

Artist Cameron Rowland is dismayed. And energised. The benches and the jackets and desk in the images here are from Rowland’s latest show 91020000 at Artists Space in New York. Continuing his minimalist installation approach, Rowland has put a few (of the bigger) Corcraft goods in the gallery space. The project is as much an extended and deeply researched essay as it is this gallery installation.

“Property is preserved through inheritance,” writes Rowland. “Legal and economic adaptations have maintained and reconfigured the property interests established by the economy of slavery in the United States. The 13th constitutional amendment outlawed private chattel slavery; however, its exception clause legalized slavery and involuntary servitude when administered “as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

To prison activists this is not new language. Even to Oprah’s List devotees this is not new. Michelle Alexander put into plain and passionate terms how the legal inequities of first, convict leasing, then Jim Crow laws and, now, expanded disenfranchisement laws in the era of mass incarceration, have maintained a “sub-class” made up disproportionately of people of colour.

Crucially, when Rowland talks of inheritance, he’s not talking about the bank accounts and assets of our parents. No, he’s talking about our shared inheritance as a nation that enjoys civic infrastructure and communities who benefit from, or not, the provision of nurturing institutions and spaces. Capitalism depends upon the movement and trade of raw materials. Roads, ports, markets, factories and comms all built upon a dependent system of inequality.

Rowland describes how convict leasing replaced a “largely ineffective” statute labor provision. And the roads in southern states got built. From there, Rowland rolls with the examples into modern day, not letting up to allow us an escape route argument of ‘This is now, That was then.’ It all connects. Read it.

Cameron Rowland, “1st Defense NFPA 1977, 2011” (2016), Nomex fire suit, distributed by CALPIA, 50 x 13 x 8 inches. Rental at cost “The Department of Corrections shall require of every able-bodied prisoner imprisoned in any state prison as many hours of faithful labor in each day and every day during his or her term of imprisonment as shall be prescribed by the rules and regulations of the Director of Corrections.” – California Penal Code § 2700. CC35933 is the customer number assigned to the nonprofit organization California College of the Arts upon registering with the CALPIA, the market name for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Prison Industry Authority. Inmates working for CALPIA produce orange Nomex fire suits for the state’s 4300 inmate wildland firefighters. (photo by Adam Reich, courtesy the artist and ESSEX STREET, New York)

Alternatively, and also, read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Case For Reparations. It looks at generations of African Americans robbed of earnings, assets and net-worth, with a focus on agriculture in the south and red-lining of properties in Chicago. Coates’ piece is not a tour de force only because of its impeccable research but because he puts figures on it.

Scholars have long discussed methods by which America might make reparations to those on whose labor and exclusion the country was built. In the 1970s, the Yale Law professor Boris Bittker argued in The Case for Black Reparations that a rough price tag for reparations could be determined by multiplying the number of African Americans in the population by the difference in white and black per capita income. That number—$34 billion in 1973, when Bittker wrote his book—could be added to a reparations program each year for a decade or two. Today Charles Ogletree, the Harvard Law School professor, argues for something broader: a program of job training and public works that takes racial justice as its mission but includes the poor of all races.

To celebrate freedom and democracy while forgetting America’s origins in a slavery economy is patriotism à la carte. Perhaps no statistic better illustrates the enduring legacy of our country’s shameful history of treating black people as sub-citizens, sub-Americans, and sub-humans than the wealth gap. Reparations would seek to close this chasm. But as surely as the creation of the wealth gap required the cooperation of every aspect of the society, bridging it will require the same.

Which brings us to the modern day. And to the darker corners of American commerce.

Let’s be clear, Rowland isn’t arguing about the merits, or lack thereof, of the existing judicial system and the rightness or wrongness of the control of prisoners. No, he’s more interested in the economic uses of the prisoners, of those bodies.

I’ll argue, in Rowland’s absence, that prisons in the U.S. are morally repugnant and a violence on poor Americans to a unconscionable degree. I’ll double back round and point to Rowland’s beautifully constructed text and visual arguments as one piece of evidence for the assertion.

I’m sure Rowland and I would agree that the over-arching forces of commerce (from which all hands are a few steps removed from the control panel and therefore responsibility) are the problem.

Now read Seph Rodney‘s review The Products of Forced Labor in U.S. Prisons on Hyperallergic.

This excerpt particularly:

But how do we conceal the theft? The question that has to be posed when people are systematically disappeared is: Where do we hide the bodies? “In prison” is only part of the answer. The deeper, more sinister response is also the most seemingly benign: we abstract them so they become only sources of labor and wealth. We reduce them to lines in an actuarial table, an oblique reference in a statute, a number in a log book. We dissolve people into fungible assets.

A lot of the time quiet gallery spaces don’t do a lot for me. They just seem sad. But when an artist can fill the space with poignancy … and especially when they are dealing with a grave matter that is–like in the case of prison labor–desperately sad, then I think it works.

Cameron Rowland: 91020000 continues at Artists Space (3rd Floor, 38 Greene St, Soho, Manhattan) through March 13. Get there if you can.

–

Cameron Rowland, “Attica Series Desk” (2016), steel, powder coating, laminated particleboard, distributed by Corcraft, 60 x 71.5 x 28.75 inches. Rental at cost: The Attica Series Desk is manufactured by prisoners in Attica Correctional Facility. Prisoners seized control of the D-Yard in Attica from September 9th to 13th 1971. Following the inmates’ immediate demands for amnesty, the first in their list of practical proposals was to extend the enforcement of “the New York State minimum wage law to prison industries.” Inmates working in New York State prisons are currently paid $0.10 to $1.14 an hour. Inmates in Attica produce furniture for government offices throughout the state. This component of government administration depends on inmate labor. (photo by Adam Reich, courtesy the artist and ESSEX STREET, New York)

Installation view of ‘Cameron Rowland: 91020000’ at Artists Space, New York (photo by Adam Reich)

Tomorrow evening there’s an intriguing discussion happening at the Mechanics Institute in San Francisco. On the panel for Incarceration and the Path to Reform are author and educator Baz Dreisinger. She is the Academic Director for the Prison-to-College Pipeline program, coordinated by John Jay College, NYC, that offers college courses to incarcerated men. San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón alongside Jacques Verduin of Insight-Out and GRIP, and former inmate and GRIP graduate Terrell Merritt make up the rest of the group.

Can’t wait.

It’s at Wednesday, February 17, 2016 from 6pm onwards.

Mechanics Institute, 57 Post Street, 4th Floor Meeting Room, San Francisco, CA 94104

Call staffer Pam Troy on 415-393-0116 for more info.

Tickets for the public are $15. SIGN UP HERE.

THE BLURB

“Fiscal and physical challenges to our penal systems as well as changing attitudes about prison reform are happening locally, nationally, and internationally. […] See how San Francisco is modeling a new paradigm for rehabilitation and issues of human rights for those incarcerated. With President Obama’s December 18th commutation of 95 non-violent drug offenders to the recent “vote- down” of funding the new jail in San Francisco, there is much to talk about.”

Dr. Baz Dreisinger

Dresinger journeyed to Jamaica to visit a prison music program, to Singapore to learn about approaches to prisoner reentry, to Australia to grapple with the bottom line of private prisons, to a federal supermax in Brazil to confront the horrors of solitary confinement, and finally to the so-called model prisons of Norway. This jarring and poignant trek invites us to rethink one of America’s most devastating exports, the modern prison system. With Oscar-nominated filmmaker Peter Spirer, Dreisinger produced and wrote the documentaries Black & Blue: Legends of the Hip-Hop Cop, and Rhyme & Punishment. Her book Near Black: White to Black Passing in American Culture was published in 2008 by University of Massachusetts Press.

Dresinger journeyed to Jamaica to visit a prison music program, to Singapore to learn about approaches to prisoner reentry, to Australia to grapple with the bottom line of private prisons, to a federal supermax in Brazil to confront the horrors of solitary confinement, and finally to the so-called model prisons of Norway. This jarring and poignant trek invites us to rethink one of America’s most devastating exports, the modern prison system. With Oscar-nominated filmmaker Peter Spirer, Dreisinger produced and wrote the documentaries Black & Blue: Legends of the Hip-Hop Cop, and Rhyme & Punishment. Her book Near Black: White to Black Passing in American Culture was published in 2008 by University of Massachusetts Press.

Jacques Verduin

Verduin has worked in prisons for 20 years, designing and running innovative rehabilitation programs. He is a subject matter expert on mindfulness, restorative justice, emotional intelligence, and transforming violence. He directs the non-profit “Insight-Out” which helps prisoners and challenged youth create the personal and systemic change to transform violence and suffering into opportunities for learning and healing. The Guiding Rage into Power (GRIP) Program at San Quentin is a year-long transformative program that provides the tools that enable prisoners to “turn the stigma of being a violent offender into a badge of being a non-violent Peacekeeper.” A former inmate and graduate of this program will be on the panel.

Verduin has worked in prisons for 20 years, designing and running innovative rehabilitation programs. He is a subject matter expert on mindfulness, restorative justice, emotional intelligence, and transforming violence. He directs the non-profit “Insight-Out” which helps prisoners and challenged youth create the personal and systemic change to transform violence and suffering into opportunities for learning and healing. The Guiding Rage into Power (GRIP) Program at San Quentin is a year-long transformative program that provides the tools that enable prisoners to “turn the stigma of being a violent offender into a badge of being a non-violent Peacekeeper.” A former inmate and graduate of this program will be on the panel.

Terrell Merritt

Merritt is from Gary, Indiana. After high school he enlisted in the Navy and was stationed in San Diego, CA. After leaving the Navy, he spend 20 years in prison for 2nd degree murder. During that time, he began to soul search and incorporate practices into his life that promote nonviolence. These include nonviolence communication, Zen Buddhism, and the GRIP Program; a yearlong transformational program that he became a facilitator of. On November 10th 2015, he was paroled after serving 20 years and 8 months in prison. He is currently working to reestablish himself into the community and to give back where he can.

George Gascón

Gascón is the District Attorney for the City and County of San Francisco. He has earned a national reputation as a criminal justice visionary that uses evidence based practices to lower crime and make communities safer. He is the first Latino to hold the office in San Francisco and is the nation’s first police chief to become District Attorney. Looking to find alternatives to incarceration for low-level offenders, DA Gascón created the nation’s first Alternative Sentencing Program to support prosecutors in assessing risk and determine the most appropriate course of action for each case. The goal is to protect victims and the community by addressing offenders’ risk factors in order to break the cycle of crime and reduce recidivism.

DETAILS

February 17, 2016 from 6pm onwards.

Mechanics Institute, 57 Post Street, 4th Floor Meeting Room, San Francisco, CA 94104

Call staffer Pam Troy on 415-393-0116 for more info.

Tickets for the public are $15. SIGN UP HERE.

HAPPY THANKSGIVING!

On the eve of Thanksgiving, it is good to remember our shared humanity. It’s also good to acknowledge our shared crimes and remember the blood spilt on the American continent. Yes, it’s imperative to celebrate common values and spiritual connection, but never at the expense of false narrative. Thanksgiving is an ideological construct to lessen the burden of a genocide perpetrated by first European and, later, White American settlers.

Yes, we need to commune and yes, we need to pause, often, and to be grateful for all we have, but let’s not wholly embrace a mythos that paints settlement of America by violent outsiders as one big picnic.

I just republished, on Medium, my 2009 Prison Photography interview with Ilka Hartmann, who photographed the Indian Occupation of Alcatraz in 1970/71.

Because our relationship to the past is our relationship to one another

Read: Photographing the Indian Occupation of Alcatraz: An Interview with Ilka Hartmann

See: Ilka Matmann’s photographs of the Indian Occupation of Alcatraz.

HAPPY THANKSGIVING!

All images: © Ilka Hartmann