You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘New York’ tag.

The War On Drugs has lasted more than 45 years and cost over $1 trillion dollars. Everyone from Rolling Stone to the Cato Institute to the Obama White House has concluded it a failure. The root of the failure is this: A nation cannot incarcerate, punish and brutalize people out of their already traumatic lives. Drug use and abuse is not solely a criminal matter; it is mostly a public health issue. People addicted to substances need treatment not cages.

The Trump Administration is cheering on its bipartisan First Step Act (and ignoring that the promised $75million for its rollout is actually only $14million the latest proposed federal budget) but the act focuses mostly on prison reform and not sentencing reform. Sure, improved conditions, better reentry support, early compassionate release and access to feminine hygiene products are all very important, but what about stemming the number of people being sent to federal prison? (Note: The First Step Act applies only to federal prisons which house only 10% of U.S. prisoners.) The Trump administration, especially during Jeff Sessions’ leadership of the Justice Department, has been obsessed with law and order instructing police forces and prosecutors to bring the full weight of the law upon people arrested for drug offenses in particular.

In this context, the Beyond Addiction: Reframing Recovery photography exhibition, curated by Graham MacIndoe and Susan Stellin, comes at the right time. See a host of images and contexts at the dedicated website Reframing Recovery. Instead of prisons, the show focuses on “the ways people have rebuilt their lives: reconnecting with their families, finding rewarding work, developing meaningful relationships with partners, peers, and others who offer support,” say Stellin and MacIndoe.

There are approximately 23 million people in the U.S. who have successfully resolved a problem with drugs or alcohol, but do we see their collapse more than their rise? Do we see their struggles more than their triumphs? I’d say the focus too often tends to be on the suffering. This exhibition shines a light on living, not just on a time of life affected by drugs. This exhibition shines a light not on life’s dark moments but on all the light and comparative lightness that former users create for themselves.

Stellin and MacIndoe also recognize the contributions of treatment providers and harm reduction services.

“Recovery is rarely a solo journey and it usually involves setbacks and hurdles, but the more we talk about it, share ideas, and embrace different paths, the more people will find their way,” they say.

It’s a large exhibition. It’s a varied exhibition. It’s optimistic. Stellin, MacIndoe and the artists are part of “a growing movement working to offer examples of success and hope to those still struggling with addiction” and, in that sense, it’s an important exhibition.

ARTISTS

Many of the contributing artists have personal experience with addiction and recovery, while others have worked closely with the people whose stories they documented. Artists include Nina Berman, Allan Clear, John Donadeo, Yannick Fornacciari, Tony Fouhse, Paul Gorman, John Linder, Luceo, Josh Meltzer, Jackie Neale and Neil Sneddon.

Nina Berman: An autobiography of Miss Wish. A multi-dimensional collaborative work focusing on the story of one woman and the intersection of sexual trauma, mental illness, addiction, and recovery.

Allan Clear: Lower East Side Needle Exchange. Photos of people, events, activism, and art from this community center at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the early 1990s.

John Donadeo: Family Ties. Portraits of John’s extended family and friends exploring the socioeconomic and familial factors that impact addiction and recovery.

Yannick Fornacciari: Heroin Days. Images and text juxtaposing Yannick’s first day on methadone with how he felt after a year of treatment.

Tony Fouhse: Live Through This. Photos of a young woman Tony met who asked for help getting into a rehab program, which enabled her to escape life on the street.

Paul Gorman: Rip and Run. Spoken word pieces and images commenting on Paul’s past drug use and his life now in recovery.

John Linder: Art Therapy. Artwork John created in a program that helps participants use art as part of a therapeutic process to address drug and alcohol problems.

Luceo: Harm Reductionists. Photos of supporters of the harm reduction movement paired with handwritten responses to question prompts.

Graham MacIndoe: Thank You for Sharing. Instagram and Facebook posts reflecting on Graham’s addiction, incarceration, and recovery, which have inspired others to share their experiences as well.

Graham MacIndoe and Susan Stellin: Re-Entry & Recovery. Portraits and interviews with people navigating life after addiction and incarceration, from a larger series documenting stories of recovery.

Josh Meltzer: Dopesick—Agents of Change. Portraits of treatment providers, healthcare workers, activists, and counselors shot for Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America, by Beth Macy.

Jackie Neale: Common Ground Tacony. A cyanotype portrait banner of Richard, who tends to a garden in the Tacony neighborhood of North Philadelphia as part of his recovery from addiction.

Neil Sneddon: Developing Recovery. Photos taken by clients Neil asked to document the people, places, and things they identified as meaningful for their recovery.

BIOS

Beyond Addiction: Reframing Recovery is curated by Graham MacIndoe and Susan Stellin. MacIndoe is a photographer and assistant professor at Parsons. Stellin, reporter and adjunct professor in the Journalism + Design department at The New School, recently completed a masters in public health at Columbia University. They have collaborated on various projects combining interviews and photography, including exhibitions, talks, and a memoir documenting Graham’s addiction, incarceration, and recovery.

DETAILS

See a host of images and contexts at the dedicated website Reframing Recovery.

Location: Arnold and Sheila Aronson Galleries, Parsons School of Design, The New School 66 Fifth Ave. @ 13th St., New York City

Dates: April 6-21, 2019

Gallery hours: Open daily 12:00–6:00 p.m. and Thurs. until 8:00 p.m.

Opening reception and panel discussion: Tues. April 9

5:30 – 6:30 p.m. reception and exhibition viewing

6:30 – 8:00 p.m. panel discussion

KAREN, 69, in a homeless shelter four weeks after her release. East Village, NY (2017)

Sentence: 25 years to life

Served: 35 years

Released: April 2017

“When I made parole plans, I thought I was going to have a good re-entry situation in the house I paroled to. I realized almost immediately that it wouldn’t work out, so I left, without anywhere else to go. Parole sent me to a homeless assessment shelter in the south Bronx. The quality of the bedding and the food was a lateral move from prison. But factoring in my freedom, there’s no question that it was an improvement. Now, I’m in a shelter run by the Women’s Prison Association. I feel safe and secure. The room is spare, with not much in it, but it’s mine. In this room, I find comfort, privacy, safety, and peace of mind.”

Working as a public defender, Sara Bennett has met a great many women who have faced struggle and hardship. Many serve, or have served, long sentences. Since 1980, the number of incarcerated women has increased by 800% in the U.S. There are nearly 100,000 women in state prisons and federal penitentiaries. A further 110,000 are in county jails, 80% of whom report having been the victim of sexual assault during their life time. Women who have been convicted of serious crimes have, more often than not, been the victims of serious abuse themselves. Irrespective of crime, I have consistently argued that mass incarceration does little to improve or heal. It does the opposite. It damages.

When facing conservative opposition, prison reformers often resort to arguments against the incarceration of non-violent people, women included. Reformers attempt to find sympathetic groups within the prison system for whom the public may be persuaded to support. This is all well and good, but it comes at a price; people convicted of violent crimes are left to rot, so to speak. For advocates such as Bennett, it is clear that long sentences achieve little and that the abuses of the prison industrial complex are wrought on all who it swallows. The Bedroom Project humanizes women who have recently re-entered society after serving long, multi-decade Life With Parole sentences.

Bennett has created a space for each of these women to reflect upon their post-release situation. They regale personal tales and they are photographed in their most personal spaces–their bedrooms. In some cases, a bedroom might be the only place some of these women can claim as their own.

Bennett is a former criminal defense attorney who most frequently represented battered women and the wrongly convicted. She uses photography to amplify her observations of the criminal justice system. Her first project, Life After Life in Prison documented the lives of four women as they returned to society after spending decades in prison. Bennett decries the “pointlessness of extremely long sentences and arbitrary parole denials”. The Bedroom Project is currently on show at the CUNY School of Law in Long Island City, New York until March 28th.

Keen to know more about Bennett’s process and motivations, I approached her with a few questions about The Bedroom Project. Scroll down for our Q&A in which we discuss the meaning of the work for both subjects and audiences.

EVELYN, 42, in an apartment she shares with a roommate five years after her release. Queens, NY (2017)

Sentence: 15 years to life

Served: 20 years

Released: April 2012

“Look where I am now. Five years ago, I came out from a little cell, started out in a halfway house, moved to an apartment, back to a transitional home, and now I’m in my own room in an apartment I share with a roommate. What can be better than this? This is happening.”

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Many of the women you photographed are living in a room in a community house, or an apartment building for returning citizens, or in a one bedroom apartment. So, they have a single room that is their own. While imprisoned, they may or may not have had a cellmate, and the degree to which they could personalise their cell would differ. No matter, they lived within walls for long periods. You’re photographing them also within walls. Tell us about why you focused on their bedrooms.

Sara Bennett (SB): It’s not the similarity to the prison cell that I’m trying to highlight, but the contrast. It’s true that most of the women now live in shared spaces, but still there’s a sense of intimacy, self, and pride. They all have items on display that would have been contraband in prison, including stuffed animals, wooden picture frames, patterned sheets, cellphones and computers. For decades, their cells were randomly inspected, they were locked in every evening, and they were forced to move at a moment’s notice. Now these bedrooms are their own.

TOWANDA, 45, in her own apartment five years after her release, with her daughter, Equanni. Bronx, NY (2017)

Sentence: 15 years to life

Served: almost 23 years

Released: October 2012

“I was in the shelter system for the first four years. It was about the same as prison. You’re confined, you can’t do anything, you don’t have your own thoughts, you’re always stressed out. It’s good to have my own apartment and pay my own bills. It’s peaceful and I feel safe.”

PP: What was the dynamic between you and the women.

SB: For many years, I was the pro bono clemency attorney for Judith Clark, who was serving a 75-year-to-life sentence for her role as a getaway driver in a famous New York Case—the Brinks robbery of 1981. All my subjects know her and my first photography project, Spirit on the Inside, is about the women who were incarcerated with her and her influence on their lives. (Spirit on the Inside book.)

The reaction to Spirit on the Inside—viewers were surprised that the formerly incarcerated women were just regular women—sparked my second project, Life After Life in Prison. I followed four women in various stages of re-entry, and I spent so much time with each of them that we really got to know each other. At the same time, I began work on The Bedroom Project, and the four women put me in touch with other potential subjects. So before I even walked in the door, my new portrait subjects were open to me. They’d seen my previous work; they knew some of my former subjects or clients; and they’d been told that I could be trusted.

I’ve ended up being a mentor or friend to almost all the women I’ve photographed.

PP: Why did you choose to include the women’s handwriting?

SB: My goal in all of my photography work is to show the humanity in people who are, or were, incarcerated. I believe that if judges, prosecutors and legislators could see lifers as real individuals, they would rethink the policies that lock them away forever. I want viewers to know what these women are thinking. Including their handwriting emphasizes that these are their words, these are their thoughts.

I asked all of them the same question: “When you see this photo I took of you, what does it make you think?” Their answers are varied and lead the viewer to all kinds of issues—from what it feels like to live in a cell, to educational and employment opportunities inside and outside prison, the difficulties in getting parole and being on parole, finding housing, and issues of remorse, regret, and forgiveness.

TRACY, 51, in her own apartment three-and-a-half years after her release. Jamaica, NY (2017)

Sentence: 22 years to life

Served: 24 years

Released: February 2014

“I imagined coming home, living in a one- or two-bedroom apartment, where one was a master and an extra room for guests. Here I have that. I call this room my “doll house,” my safe haven. I feel at peace. I’ve finally unpacked. I spend a lot of time in here. I take pride in everything. I put more into this room than into the kitchen. I know I need to eat, but my room is my nutrition.”

MIRIAM, 51, in transitional housing two months after her release. Corona, NY (2018)

Sentence: 20 years to life

Served: 30 years

Released: December 2017

“This room is my room. A place of my sanity unlike the one in prison. No one will bother me if I’m heard talking to myself. I can think clearly, I can breathe, I can live my way, dress my way, look at things my may. Move my furniture around my way. I love my room. It’s mine—all mine and no one can say anything about it.”

PP: What were the main victories for these women post release? What were their main challenges?

SB: Each woman’s circumstance is unique and so their challenges and victories are different. I’d say the biggest and most immediate challenge is finding housing. There are some re-entry programs that provide housing that is either temporary (up to six months) or semi-permanent, and many of the women were lucky enough to get into one of those programs. Some of the women ended up in homeless shelters and some have bounced around from place to place. I know two women who went home to live with family but both ended up moving to housing programs, in part because those programs offer a community that feels familiar and supportive.

Some of the women have completed educational degrees since coming home, some have found rewarding jobs and relationships, and unsurprisingly, the longer a woman has been home, the more stable she becomes.

But most have difficulty finding a job, let alone a decent job, and almost all of them have financial struggles. Many get benefits but that amount is paltry.

It’s mind boggling how quickly the women seem to adapt, how resilient they are, and how they take challenges in stride. Remember, my subjects spent anywhere from 15 to 35 years in prison. The outside world changed radically in that time. As Aisha, one of my subjects says, “It’s like putting a kindergartner in college”.

AISHA, 45, in a house she shares with 5 other women 14 months after her release. Flushing, NY (2017)

Sentence: 25 years to life

Served: 25 years

Released: June 2016

“When I was released, I didn’t feel overwhelmed; I felt as though I was right where I was supposed to be. Later though, the feeling of being overwhelmed came as I found myself on the business side of life: food shopping, rent, bills, metrocards, etc. That was all new to me because I lived at home with my mom until I was arrested. My children were one and three years old when I left them and I felt as if they were one and three the whole time I was away. I feel that way about myself now. I was arrested when I was 19 and being in this big, unfamiliar, advanced world makes me feel like a 19-year-old trapped in a 45 year old body. I am both happy and grateful to be out here, but it’s like putting a kindergartener in college.”

VALERIE, 62 in an apartment she shares with a roommate. Bronx, NY (2018).

Sentence: 19 years to life.

Served: 17 years (granted clemency by Governor Andrew Cuomo).

Released: January 2017

“I got my freedom. That’s true! But it’s not the same as being free free. I like to travel. I used to go to VA, to PA, and the casinos and the boardwalk in Atlantic City. I love the beach. But I can’t go anywhere without my PO’s permission. If I want to go to a play or a concert, I need my PO’s permission. Until I get off parole, my life is messed up. I can’t do what I want.”

PP: Release from prison is not easy thing. Many of the women were given “numbers-to-life” sentences. Some got out on their parole date, others years after their first parole eligibility. What has been the situation in NY state for releasing persons who’ve served long sentences? Has parole and release become more common recently?

SB: When I first became an attorney in 1986, there was a presumption of parole. If, for example, a person had a sentence of 15 years to life, then she’d likely be released after serving her 15 years, provided that she hadn’t been in serious trouble in the few years prior. But when Governor Pataki took office in 1995, that presumption changed. And no matter how people spent their time in prison—working in trades, earning college degrees, setting up programs, having excellent disciplinary records, living in honor housing—they were repeatedly denied parole based on the one factor that will never change: the nature of the crime they committed.

I like to think that the parole system in New York State is starting to change. In the last six months, the number of parole grants has steadily increased, in part because Governor Andrew Cuomo has had the opportunity to appoint new parole commissioners and in part because of a culture shift that recognizes that, we, as a society, lock people up for far too long. Still, we have a long way to go.

CAROL, 69, in a communal residence four years after her release. Long Island City, NY (2017)

Sentence: 25 years to life

Served: 35 years

Released: March 2013

“When I was inside, I dreamed of getting out, getting a job, travelling a little bit. But by the time I got out, my health was bad. Basically, that changed all plans. I wish I could do more, but I’m at peace. I have my grandson, Cecil. He’s precious.”

PP: What have been the audiences’ responses to the work?

SB: The photos are currently facing out onto a busy street in Queens, NY and I’ve eavesdropped as passersby have studied the portraits and talked to each other. I’ve never heard anyone say, “you do the crime, you do the time.” Rather, passersby seem sympathetic, drawn in, and incredulous at the amount of time that the women have spent in prison. I’ve also moderated more than a dozen panel conversations with my subjects, and the audiences have been very responsive to the women. No matter what the women’s pasts might have been, today they are hard-working, loving, resilient, optimistic people, and the audience seems to understand that they have earned second chances.

PP: Do prisons work?

SB: That’s such a loaded question that I’m not sure how to answer it. Suffice it to say that in this country we incarcerate way too many people for way too long under conditions that are dehumanizing and obscene. In other countries, imprisonment itself is the punishment, but the conditions themselves are not punitive and abysmal.

PP: In extension of your photos and the women’s own testimonies, what would you like to impress upon members of the public about improvements in the criminal justice system?

SB: For a long time, most of the conversation around changing the criminal justice system has focused on non-violent felony offenders. President Obama talked a lot about non-violent felony offenders and low-level drug offenders. I’m concerned about people with really lengthy, or life sentences, those who are either repeatedly denied parole or don’t even have that possibility. That’s why my only criteria for The Bedroom Project was that the subjects had a life sentence. (A life sentence doesn’t really mean life in prison unless it’s life without parole. A sentence of say, 25 years to life, means that after 25 years a person becomes eligible for parole.) I wanted to really drive home the point: people with life sentences are ordinary (in the best sense of the word) human beings. They deserve second chances.

MARY, 51, with her niece, Trish, in her own apartment 19 years after her release. Brooklyn, NY (2017)

Sentence: 15 years to life

Served: 15 years

Released: May 1998

“I’ve been home 19 years, but re-entry is a lifetime process. In many ways prison is with you forever. Still, the impact is a lot less than it used to be. For years, everything I did, everything I thought about, reflected back to prison. It was about 15 years out—I did 15 years in—that I stopped connecting to that girl I was in prison. Maybe you have to do the same amount of time outside as you did inside until you feel FREE from it.

”LINDA, 70, in her own apartment 14 years after her release. Albany, NY (2017)

Sentence: 17 years to life

Served: 14 years. Granted clemency by Governor George Pataki

Released: February 2003

“I love my apartment. The building is clean. I feel safe and at peace. I been here 10 years. I been out of prison 14 years. It’s so hard when you get out. I just stayed strong. With a friend’s help I got a job as a housekeeper in a hospital. I stayed there for 9-1/2 years. Then I retired. As of now I have to try very hard to stay on my budget finance wise. I have a good family & friends in my life. I thank the life I have now. And I thank God everyday that I am alive and safe. Thank you God.”

PP: What effects (positive and/or negative) do prisons and reentry have on women? What are their needs that often get overlooked?

SB: One of the saddest things to me about prison is that it can be the first time a woman has found safety in her life. Most women in prison have been victims of gender-based violence. I’ll never forget a client telling me that she got her first good night’s sleep when she went to prison, no longer subject to abuse by her boyfriend. So, in that sense, prison initially brought some peace as well as a sense of community and self awareness to some of the women I know. Of course, that came at the extremely high cost of the loss of freedom.

In general, women have fewer outside contacts than men and lose touch with their families much quicker than men do. So they are very isolated from the outside world and come home to a world that has moved on without them. They find a society that puts up a series of hurdles: they are required to attend state-mandated programs, barred from inexpensive public housing and banned from voting. In addition, they face travel limitations and curfews that make visiting family and working more difficult. When they eventually become eligible to be released from parole, they are often denied without explanation.

I hope the stories of these women remind us of the countless people still in prison who, like them, deserve that same chance to build a life on the outside.

PP: Thanks, Sara.

SB: Thank you.

Artist-filmmaker Nirit Peled and director Sara Kolster have produced A Temporary Contact, a real time series of text messages and short videos delivered via WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, that allows users to join family members as they journey from New York city to upstate prisons and back.

Over 30-hours, beginning at 10pm the evening after you sign up, you’ll receive at first few texts and then consistent volley of 22 short videos. The main protagonist is Amanda, a 20-year-old from Brooklyn who is visiting her brother, but other women speak to the camera and relay their experiences. Most videos are 45 seconds long and shot from the aisle of the bus. Gas station and restroom breaks are a relief for all. Audio is overlaid the blurred land at 60mph. I include a few screencaps for the purposes of this commentary.

As we know, the majority of new prison construction in the past 30 years has occurred in rural America and in post-industrial towns. The “logic” was to replace the dead agriculture and manufacturing jobs with prison jobs. However, the small (and ever-decreasing) benefits that may have been brought to struggling, job-scarce populations are eclipsed by the hardships wrought upon prisoners and their distant friends and families. A Temporary Contact takes us on the weekend journey that family–mostly women and children–make; a journey essential for keeping family ties. Bear in mind that, for incarcerated persons, maintaining close relations with loved ones is the most important factor in helping them stay out the system after release.

New York state, as with other large states such as California, Texas and Illinois, is one of the worst offenders in siting prisons hundreds of miles from the communities from which prisoners are extracted. A Temporary Contact offers users a moment inside the collateral damage done by this particular extended and prohibitively expensive travel.

Some thoughts on the title: Temporary contact is fleeting, it’s real but not sustained. The title simultaneously recognises the intermittent opportunities that family have to make in-person visits (those with financial means and time, might make the journey as often as twice a month), but also points to our passing point of contact with a time-consuming (and likely foreign) travel-commitment which prisoners’ loved ones regularly and necessarily sign up for.

Despite the journey’s substantial 30-hour timeframe, it’s one that is largely self-contained and not seen … except for maybe the lines of people waiting for pick up at 34th street or Columbus Circle in NYC late on a Friday or Saturday evening. (For an in-depth photo essay on prison buses, please see Jacobia Dahm’s work; read the interview she and I did; and then read this follow-up conversation Dahm had with Candis Cumberbatch-Overton, who Dahm photographed as she visited her husband John.)

There are many revealing moments in A Temporary Contact and it’d be foolhardy to describe them; you should just sign up for the messages toy our own smartphone. The presence of time–and time seen–is part of the art’s structure! That said, I thought it instructive that immediately following their departure from the prisons, the women shared photos of their loved ones and talked about the costs to have the portraits made.

“The only thing we take out the visits,” says Amanda, “are the pictures.”

The women compare costs of a single Instax picture. In one prison it is $2 per photo. In another it is $4. They talk about physical changes, new facial hair, how they all appear in one another’s photos. They laugh and gripe about the quality of the murals in front of which they must stand for the portraits.

Visitors are allowed to have five pictures made on each visit. Despite the huge expense (relative to single prints in free society) the women tend to get five. Max out on memories. Optimise the presence of their loved one in the world. A photo is a thin slice of time, but it is a substantial presence in the free world of someone who is behind bars in a limbo-state of social death.

It seems that every photography conference these days is talking about getting beyond the frame, and using new technologies and digital platforms to tell stories. Peled and Kolster propose a model that delivers important, compelling content with direct efficiency. The bar for access is as low as it gets; who doesn’t have WhatsApp or Facebook on their phones at this point? The temporal quality of the project is key. The success of A Temporary Contact rests on the fact that, every one or two hours, users are prodded with gentle reminders of other’s devotion to time … time spent in love and support of prisoners.

I wholly recommend A Temporary Contact. I learnt new things, I think you will too.

–

A Temporary Contact was developed within the framework of the veryveryshort competition, a NFB and ARTE co-production in collaboration of IDFA Doclab. Very very short is a collection of 10 interactive projects for smartphones, exploring the theme of mobility through very, very short experiences – all under 60 seconds.

Credits

Creators: Nirit Peled & Sara Kolster

Camera: Aafke Beernink

Editor: Wietse de Swart

Additional editing: Paul Delput

Sound mix: Sander den Broeder

Color: Maurik de Ridder

Developer: Martijn Eerens

Scripting: Wireless Services

Music: Amit Gur & Itai Weissman

Cast: Amanda, Diamond, Gina, Latoya and Stephany

Research help: Ilja Willems, Five Mualimm-ak, Ray Simmons

Special thanks: Katie Turinski, Junior from Flambouyant Transportation Inc., Het Raam, Hortense Lauras

I wrote recently about Davi Russo‘s family portraits made inside two New Jersey State prisons between 1987 and 2007: 20 years of prison polaroids chart son’s resolve, love, and only contact with dad.

The Polaroids chart visits he, his mother, sister, grandparents and friends made to see his father David who was incarcerated on suspicion of murder in 1984, stood trial, and was found guilty and sentenced, in 1987, to life plus 20 years. He has been eligible for parole since 2010 but remains in prison today. Russo, a director and photographer these days, was nine years old at the time of his father’s conviction.

Russo hoped sharing his experience might help others get free of the stigma of incarceration too.

“Growing up with Shawshank Redemption and all the horrible prison TV shows, I wanted to take authorship,” explains Russo. “I had a chance to put something different together. And it was legitimate. Polaroids are thought of as the most fun type of photography. Super quick, on the beach, snap, shake it. The world is perfect! Shoot it on polaroid! But not for me. I didn’t experience polaroids that way and I knew I wasn’t the only one.”

Russo was reluctant to share the photos publicly for many years and when he finally did he asked his father to write a reflection on the collection. Instead, his father wrote single memories on Post-It notes of each photo … of each moment they stood before the camera. Those written memories became the captions for each image–an unexpected and personal twenty year narrative. Therefore, I encourage you to visit the series, which Russo has named Picture Time, on Russo’s website and read the full captions. There too, you will find essays by Russo’s sister and mother.

–

Read and see more: 20 years of prison polaroids chart son’s resolve, love, and only contact with dad.

The love affair between street photographers and New York City is rich, lucid, sometimes sordid and, seemingly, unbreakable. Images shot on the fly on the streets of the Big Apple form a significant part of the canon of photographic history — think Helen Levitt’s photos of kids at play, Weegee’s crime scenes crowds, Bruce Davidson’s subway, Jill Freedman’s brilliantly observed moments, Louis Mendes’ fifty-years of street portraits, and Jamel Shabazz’s polychromatic pictures of hip-hop culture. Perhaps the patina of time leads us to romanticize these bygone eras? Perhaps the stand of time between us and the fashions, hairstyles, automobiles and shop-fronts of yesteryear makes looking just simple, uncomplicated fun? Either way, Carrie Boretz’s work is wonderful.

Between 1975 and 1994, Boretz traversed NYC. From Brooklyn to Midtown Manhattan, from Queens to the West Village, and from Harlem to Studio 54, Boretz sought out busy, public scenes that would turn viewers’ attention back toward the everyday wonder of everyday life.

Street: New York City — 70s, 80s, 90s is a book of 103 images from the New York boroughs. It’s an elegy to a time when the city was a bit rough and tumble.

“New York seems less interesting now and more sanitized,” says Boretz.

Carrie Boretz’s Street is published by PowerHouse Books.

Read and see more: These amazing street photos show 20 years of New York’s gritty glam era—through one woman’s eyes

KNIVES, BY JASON KOXVOLD

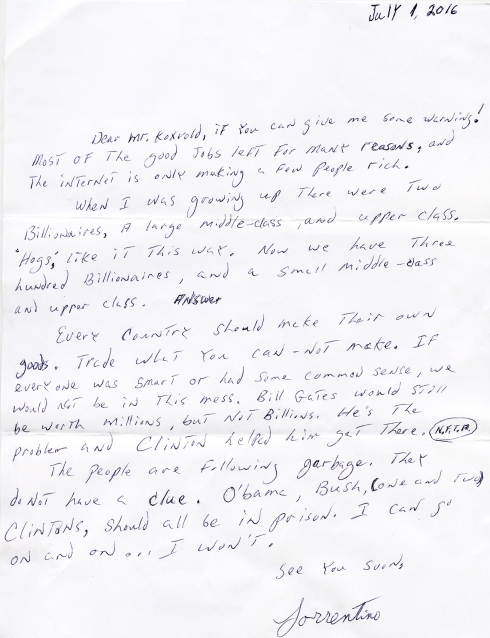

In 2004, the Schrade Knife factory in Ellenville, NY closed its doors for the last time. Operations were moved to China and, almost overnight, 500 locals lost their jobs. Suppliers and services in the area lost business too and the towns of Ellenville, Napanoch and Wawarsing where photographer Jason Koxvold lives have had to adapt to avoid massive economic injury. In 2015, Koxvold began documenting his hometown and its residents. Since the closures of factories in this pocket of the Hudson Valley, Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch is the biggest employer in the town.

The project Knives, says Koxvold, “serves as a microcosm of the larger issues facing the United States, grappling with the effects of automation and outsourcing, cuts in services, and the rise of identity politics.”

It includes portraits of prisoners, employees and former prison officers. The motif of the knife functions as a literal description of a disappeared economy and identity marker for the people of Wawarsing, but it also acts as a metaphor to the silent violence of both globalisation and incarceration. Whereas a gun mows people down in a hail of bullets, a knife cuts through and guts with a quiet, single swift action. The damage can be deep, precise. An unspectacular assault that is so often lethal.

I admire the way Koxvold has gone about peeling back the layers of his home-region. He managed to gain access into the local prison photographing prisoners. Without trying, he found many locals who had worked in the prison. He often picked up visual threads that ended up looping back to the fact of incarceration.

Koxvold is currently crowdfunding monies for the photobook Knives. We chatted about how the prison industrial complex manifests itself in his work, how it functions in the community and how exactly he got inside.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Do prisons work?

Jason Koxvold (JK): As a Norwegian citizen, my answer would be yes. As a permanent resident of the United States, my answer is not as well as they should.

With that said, during the making of this project I’ve become aware of the work of the Bard Prison Initiative, and programs like that are to be applauded; but in general in this country, it’s my understanding that prisons are seen as a punishment more than an opportunity to rehabilitate. That approach is unsustainable.

PP: You’re crowdfunding to raise money for Knives book. There’s no mention of the prison in the Kickstarter video but you’ve explained to me that the prison is “woven more deeply through the work than uncaptioned photographs might suggest.” Can you flesh that out a bit?

JK: Because the prison has been a feature of the town for so long, and there weren’t many other opportunities for employment in the region, it turned out that some of the men I photographed for this project had worked as prison guards for large portions of their lives.

Specifically, one of the characters had worked in a prison for 25 years, and possessed a wealth of knowledge about the place. His is the knife with “JUSTICE” engraved into the blade, which seems perverse in some regard; he’s written comments on internet forums defending the use of the phrase “Nigger Chaser” in the name of a knife. So this history of the application of violence is etched deeply into the soul of the town, even as it now finds itself emasculated and adrift.

PP: At what point did Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch become a subject in Knives?

JK: Fairly early on in my research it became clear that it would be impossible to ignore it.

PP: Why is the prison was important?

JK: The prison looms over the town in some way; it’s an imposing, gothic style building that can be clearly seen from all approaches, despite being a secretive location. At first – not knowing much about the penal system here – I was under the impression that the prison housed inmates from the region, and assumed that would include some former Schrade employees, but primarily they are from New York City. That also changes the makeup of the town to some degree, as spouses and families move to the area to make visitation less onerous.

PP: What did you do to depict the prison?

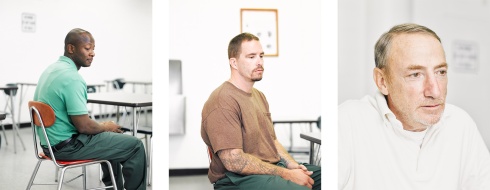

JK: I made portraits of three men inside the prison, and some exteriors of how the prison relates to the landscape and the town around it.

PP: What did you do to connect (or not) with those incarcerated and working there?

JK: My initial outreach was to the NYS Department of Corrections public affairs office, to explain my project and what I hoped to achieve. I wrote letters to a group of inmates, outlining my idea and asking if they would like to participate.

PP: You say Knives raises more questions than answers. I like it when you say you’re interested in ambition, failure, hubris. But still, it seems like the failure for us to imagine a different but improving future leads people to think that jobs might come back, and I think that accounts for Trump’s appeal in the Rust Belt. Whether he could spark an impossible resurgence or not, matters less than the fact he promises he will. As best as you can estimate, what is the future for Wawarsing?

JK: The town is working to turn things around; tourism, which was a huge business in the Catskill region in the middle of the 20th century, is what people are pinning their hopes on, and the area has seen considerable growth in that regard in recent years. There’s a great theatre, Shadowland Stages, that produces several plays a year. For some time there was talk of a new casino, but ultimately another town won the bid. In place of that, there’s now a multimillion dollar sports complex in the works.

PP: What difficulties or successes did you encounter while pursuing a narrative about Eastern Correctional Facility?

JK: My original intent included making portraits of prison guards and interiors of the prison, specifically with the intent of drawing contextual lines between this secure, sanitized inner environment and the world outside, but I was limited to the visiting area and employees were off-limits.

Even determining who was currently incarcerated at Eastern was challenging; I had to file a Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) request, which operates under an archaic system. After some correspondence, I scheduled visits to make portraits of three inmates, not knowing what they would look like or what to expect; they were very patient and generous with their time.

JK: Interestingly, photographing the exterior of the prison was more challenging than getting inside. I tend to be quite specific about weather for my exteriors, but DOCS doesn’t necessarily have the infrastructure for rapid approvals of media visits, and certain areas that I strongly wanted to photograph were absolutely off limits.

PP: What are local attitudes toward the prison?

JK: My sense is that there’s a grudging acceptance of it. People probably wish it was elsewhere, but at the same time it provides jobs for the town.

PP: You grew up in Britain. Do you see the U.S. in a particularly different way?

JK: I grew up around Windsor and Egham, but I’ve spent the whole of my adult life in the United States. I formally arrived a few months before 9/11, and unfortunately, I think that terrible event achieved its goal. 15 years of war – which is the subject of my other major project, currently in progress – has changed the country radically for the worse, in my opinion.

PP: What next for the work?

JK: My intent is to have the book ready to go to press quite rapidly after the Kickstarter is complete; it will include some new images that haven’t been shared before; and some of the work will be shown at the Davis Orton Gallery in June and July.

PP: Good luck, Jason. Thanks for chatting.

JK: Thank you.

BIO

Jason Koxvold (b. 1977) is a fine art photographer based between Brooklyn and Upstate New York. Follow his activities through his website, Instagram, Twitter and Vimeo.

Support the Kickstarter for the Knives photobook.

The Davis Orton Gallery in Hudson, NY, has just put out an open call for photography related to prisons and incarceration. They’re seeking work about prisons, prison towns, neighbours, families and children, guards, incarcerated persons and returning citizens. Landscapes, portraits and still lifes are offered as suggestions but I’d hazard they’ll take any type of imagery and I encourage the pushing of boundaries.

“This is a topic I have long wanted to present,” says gallery owner Karen Davis. “[Mass incarceration] is not a topic commonly found in our type of gallery.”

Bravo to Davis Orton to getting stuck in to the issue.

Details on how to submit your work here. The dates of the show are June 24th to July 22nd. Deadline for entry is June 6th.

From the open call, Davis Orton will select two portfolios to be included in the show. They’ll go alongside works by Joe Librandi-Cowan and Isadora Kosofsky, who anchor the exhibition.

During the run of the show, the Prison Public Memory Project (one of the most intriguing and layered public research projects I know) will be facilitating film screenings, discussions and presentations relating to mass incarceration.

This year marks 200 years since Auburn Prison went in to operation. Joe Librandi-Cowan grew up in the shadow of massive maximum-security prison in upstate New York. Over the past three years, Librandi-Cowan has been photographing the neighborhoods around the prison (now called Auburn Correctional Facility), has been meeting locals, diving into archives and exhibiting the work within the region. His main body of work is The Auburn System, titled after the Auburn System of prison management that added hard labour to the Philadelphia System of solitary, penitence and prayer. His photobook Songs of a Silent Wall brings together archive images of American prisons.

Librandi-Cowan has contempt for the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) in the United States and the manner in which its decentralized and embedded nature allows for its silent persistence. His work mounts a narrative that writes Auburn into the early chapters of the development of the PIC. It’s not a narrative closely examined by others in his hometown. Shaping and presenting the work has not been without its challenges.

It is Librandi-Cowan’s negotiations between critiquing the system and maintaining empathy for ordinary people who work in it–who are also swallowed by it–that fascinate me. Not least, because other image-makers focused on prisons are dealing with similarly delicate negotiations.

I’m grateful to Librandi-Cowan for making time to answer my questions.

Scroll on for our Q&A.

Q&A

PP: How did your work on Auburn Prison come about? Is it still ongoing?

JLC: The project formed into the focus of my undergraduate studies and eventually into my thesis work. The project is ongoing. The work requires a slow, long-term approach. While Auburn is my hometown, I still struggle to understand and represent it visually. My relationship to Auburn, much like the town’s relationship to the prison industry, is complex. I critique and question the history of an institution that has almost always supported the community. The fact that I am a member of the community, forces me to move slowly and carefully.

The history takes a while to sift through, the relationships I make with fellow Auburnians take a while to forge, and figuring out how to represent and combat the prison industrial complex isn’t something that is simple to figure out.

PP: When did you first start thinking of the prison as a topic for your art and inquiry?

JLC: The prison sits in the middle of the city. Many members of local families, generations deep, have been employed by the prison industry. Growing up, I was vaguely aware that some of my family had worked in the prison, but I never gave the prison – which was down the street from where I lived, always in view – much of a thought.

I knew little bits about the prison’s history – that it was one of the oldest prisons in New York State, and that it was the first place to host an execution by electrocution – but the prison, and ideas related to imprisonment, were seldom discussed or explained. I never questioned or understood the prison beyond it being a place for employment.

It took me a while to realize that it wasn’t necessarily normal to have a prison down the street or to have a family member or neighbor that worked inside a prison.

JLC: As I got older, I began to learn more about the prison system, mass incarceration, the economics involved and I began to realize that the prison had a much larger influence on my community than I had initially thought or understood. I began making images to make sense of the complicated role the prison has had with my hometown, with history, and with myself as a young person living in the town. I began photographing in an attempt to make sense of the prison system from the lens of a prison host community, but immediately I realized that it further pushed me to question it.

PP: Where have you presented this work?

JLC: I have presented this at the Cayuga Museum of History and Art, which is Auburn’s local history museum. I have also shown selections of the work at LightWork in Syracuse, NY, and I recently opened a show at SUNY Onondaga.

PP: When you showed it in Auburn itself how was it received?

JLC: Reactions varied – it was positive, negative, and also a bit static/unresponsive. Much of the feedback I received were initial aesthetic responses, and not feedback on the conceptual aspects or questions the work asked.

The prison is a top employer within the community, so people are seemingly reluctant to critique or question the role of the prison, its historical implications, or what the hosting of a prison means for a community.

While showing the work in Auburn, I made it clear within my presentation that I was questioning Auburn’s role within the prison industrial complex – past and present – and that I was interested in finding a way within our community to talk about the increasing problem of mass incarceration within the United States.

JLC: I found this information to be much more difficult to present and discuss within Auburn because so many within my community are directly involved with the correctional system. It was incredibly difficult to find ways to talk about what the work questions without the perception that I was criticizing the generations of people within my community who work or have worked at the prison. Finding productive ways to critically engage, discuss, and question the livelihood of many in my community has been very difficult.

In turn, the response to the work often ends up being extremely limited. Employee contracts won’t allow for correctional officers to discuss some of these issues with me, nor they do not want to talk ill of their work. Many people within my community have a difficult time reasoning with my questioning of the prison system; their relationships to it are complex, deep, and difficult to reckon with.

While many may generally agree that the prison system doesn’t function properly or fairly, Auburn’s relationship to its prison doesn’t seem to allow for a communal discussion on the matter.

PP: You suggested to me in an email that your worry over local reactions have effected the way you edit and present?

JLC: I wouldn’t say that I’ve necessarily changed the work, but I often worry that the project, and that the directness of my stance on the prison industry, may do damage to my community – especially when presented internally. Auburn has bore witness to much trauma. It has direct and early links to the Prison Industrial Complex, the electric chair, and to correctional practices that have helped shaped modern day incarceration. Condensing and presenting that information to the community almost produces and perpetuates this trauma. While it’s not the community’s direct fault, my questioning of these practices and histories has the potential to produce the feeling that the community itself is to blame.

While it is important to combat mass incarceration and the toxic attitudes that prison work can breed, I believe it’s also important to realize and remember that prisons have direct effects on the people who work within them and on the communities that host them.

To me, the ability of many within my community to navigate between the daily entrapment of prison walls and civilian life, begins to raise many questions about how traumas and toxic attitudes are transferred and perpetuated within my community and within society in general.

JLC: Prisons not only affect incarcerated individuals – they affect those who staff the prisons, the people close to those staff too. They affect towns that host prisons and communities from which members are extracted to then be incarcerated.

Prisons shape, and are shaped, by local and regional economies connected to the prison industry, and attitudes towards race – the list goes on. I’m trying to show that the web of the prison industrial complex, while much closer to my hometown than others, is something, often almost invisible, that is local to almost every American.

While I doubt many would pick prison work as their first employment opportunity, it is one of the only financially stable options within the Auburn area. Attacking the industry that financially provides for many within the community doesn’t seem to be the best way to have these conversations or to figure out alternatives or answers to the prison.

As I continue this project, I am attempting to find ways to properly and effectively critique mass incarceration and the Prison Industrial Complex without alienating or further damaging my subjects – whether they be community members, correctional officers, or incarcerated individuals, or returning citizens.

PP: What is gained and what is lost by such slow and reflexive approach?

JLC: Being cautious and thoughtful about how the work may impact the actual people that the work represents will only help further the project and its possible impacts.

Much of the contemporary work on prisons deals with incarcerated individuals, however, I’m becoming increasingly interested in figuring out how conversations and representations of others within the prison industrial complex can impact and change our discussions on mass incarceration. Maybe if it can be shown that mass incarceration negativity effects all within the equation, different sources of change may occur?

I believe The Auburn System functions well outside of Auburn because distance from the work allows for a more general discussion around mass incarceration. But showing the work within Auburn has made me rethink how it should function within the town.

PP: Thanks, Joe

JLC: Thank you, Pete

–

JOE LIBRANDI-COWAN

Follow Librandi-Cowan‘s work on Instagram, VSCO, Facebook, Vimeo, Tumblr and Twitter.