KNIVES, BY JASON KOXVOLD

In 2004, the Schrade Knife factory in Ellenville, NY closed its doors for the last time. Operations were moved to China and, almost overnight, 500 locals lost their jobs. Suppliers and services in the area lost business too and the towns of Ellenville, Napanoch and Wawarsing where photographer Jason Koxvold lives have had to adapt to avoid massive economic injury. In 2015, Koxvold began documenting his hometown and its residents. Since the closures of factories in this pocket of the Hudson Valley, Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch is the biggest employer in the town.

The project Knives, says Koxvold, “serves as a microcosm of the larger issues facing the United States, grappling with the effects of automation and outsourcing, cuts in services, and the rise of identity politics.”

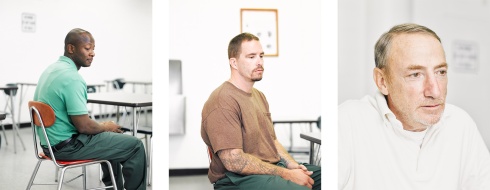

It includes portraits of prisoners, employees and former prison officers. The motif of the knife functions as a literal description of a disappeared economy and identity marker for the people of Wawarsing, but it also acts as a metaphor to the silent violence of both globalisation and incarceration. Whereas a gun mows people down in a hail of bullets, a knife cuts through and guts with a quiet, single swift action. The damage can be deep, precise. An unspectacular assault that is so often lethal.

I admire the way Koxvold has gone about peeling back the layers of his home-region. He managed to gain access into the local prison photographing prisoners. Without trying, he found many locals who had worked in the prison. He often picked up visual threads that ended up looping back to the fact of incarceration.

Koxvold is currently crowdfunding monies for the photobook Knives. We chatted about how the prison industrial complex manifests itself in his work, how it functions in the community and how exactly he got inside.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Do prisons work?

Jason Koxvold (JK): As a Norwegian citizen, my answer would be yes. As a permanent resident of the United States, my answer is not as well as they should.

With that said, during the making of this project I’ve become aware of the work of the Bard Prison Initiative, and programs like that are to be applauded; but in general in this country, it’s my understanding that prisons are seen as a punishment more than an opportunity to rehabilitate. That approach is unsustainable.

PP: You’re crowdfunding to raise money for Knives book. There’s no mention of the prison in the Kickstarter video but you’ve explained to me that the prison is “woven more deeply through the work than uncaptioned photographs might suggest.” Can you flesh that out a bit?

JK: Because the prison has been a feature of the town for so long, and there weren’t many other opportunities for employment in the region, it turned out that some of the men I photographed for this project had worked as prison guards for large portions of their lives.

Specifically, one of the characters had worked in a prison for 25 years, and possessed a wealth of knowledge about the place. His is the knife with “JUSTICE” engraved into the blade, which seems perverse in some regard; he’s written comments on internet forums defending the use of the phrase “Nigger Chaser” in the name of a knife. So this history of the application of violence is etched deeply into the soul of the town, even as it now finds itself emasculated and adrift.

PP: At what point did Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch become a subject in Knives?

JK: Fairly early on in my research it became clear that it would be impossible to ignore it.

PP: Why is the prison was important?

JK: The prison looms over the town in some way; it’s an imposing, gothic style building that can be clearly seen from all approaches, despite being a secretive location. At first – not knowing much about the penal system here – I was under the impression that the prison housed inmates from the region, and assumed that would include some former Schrade employees, but primarily they are from New York City. That also changes the makeup of the town to some degree, as spouses and families move to the area to make visitation less onerous.

PP: What did you do to depict the prison?

JK: I made portraits of three men inside the prison, and some exteriors of how the prison relates to the landscape and the town around it.

PP: What did you do to connect (or not) with those incarcerated and working there?

JK: My initial outreach was to the NYS Department of Corrections public affairs office, to explain my project and what I hoped to achieve. I wrote letters to a group of inmates, outlining my idea and asking if they would like to participate.

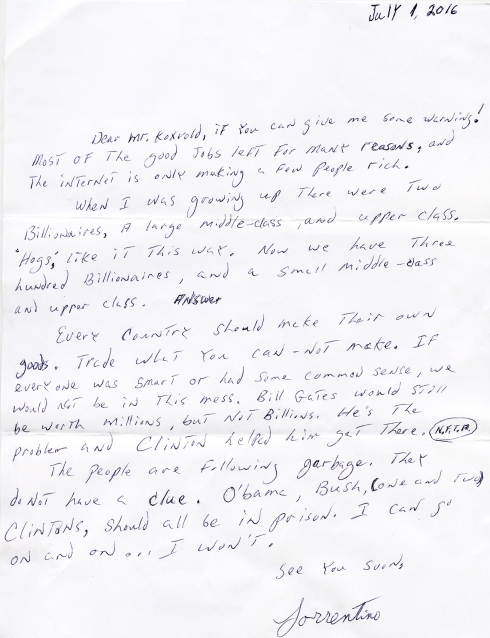

PP: You say Knives raises more questions than answers. I like it when you say you’re interested in ambition, failure, hubris. But still, it seems like the failure for us to imagine a different but improving future leads people to think that jobs might come back, and I think that accounts for Trump’s appeal in the Rust Belt. Whether he could spark an impossible resurgence or not, matters less than the fact he promises he will. As best as you can estimate, what is the future for Wawarsing?

JK: The town is working to turn things around; tourism, which was a huge business in the Catskill region in the middle of the 20th century, is what people are pinning their hopes on, and the area has seen considerable growth in that regard in recent years. There’s a great theatre, Shadowland Stages, that produces several plays a year. For some time there was talk of a new casino, but ultimately another town won the bid. In place of that, there’s now a multimillion dollar sports complex in the works.

PP: What difficulties or successes did you encounter while pursuing a narrative about Eastern Correctional Facility?

JK: My original intent included making portraits of prison guards and interiors of the prison, specifically with the intent of drawing contextual lines between this secure, sanitized inner environment and the world outside, but I was limited to the visiting area and employees were off-limits.

Even determining who was currently incarcerated at Eastern was challenging; I had to file a Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) request, which operates under an archaic system. After some correspondence, I scheduled visits to make portraits of three inmates, not knowing what they would look like or what to expect; they were very patient and generous with their time.

JK: Interestingly, photographing the exterior of the prison was more challenging than getting inside. I tend to be quite specific about weather for my exteriors, but DOCS doesn’t necessarily have the infrastructure for rapid approvals of media visits, and certain areas that I strongly wanted to photograph were absolutely off limits.

PP: What are local attitudes toward the prison?

JK: My sense is that there’s a grudging acceptance of it. People probably wish it was elsewhere, but at the same time it provides jobs for the town.

PP: You grew up in Britain. Do you see the U.S. in a particularly different way?

JK: I grew up around Windsor and Egham, but I’ve spent the whole of my adult life in the United States. I formally arrived a few months before 9/11, and unfortunately, I think that terrible event achieved its goal. 15 years of war – which is the subject of my other major project, currently in progress – has changed the country radically for the worse, in my opinion.

PP: What next for the work?

JK: My intent is to have the book ready to go to press quite rapidly after the Kickstarter is complete; it will include some new images that haven’t been shared before; and some of the work will be shown at the Davis Orton Gallery in June and July.

PP: Good luck, Jason. Thanks for chatting.

JK: Thank you.

BIO

Jason Koxvold (b. 1977) is a fine art photographer based between Brooklyn and Upstate New York. Follow his activities through his website, Instagram, Twitter and Vimeo.

Support the Kickstarter for the Knives photobook.

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article