You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Portraiture’ tag.

This year marks 200 years since Auburn Prison went in to operation. Joe Librandi-Cowan grew up in the shadow of massive maximum-security prison in upstate New York. Over the past three years, Librandi-Cowan has been photographing the neighborhoods around the prison (now called Auburn Correctional Facility), has been meeting locals, diving into archives and exhibiting the work within the region. His main body of work is The Auburn System, titled after the Auburn System of prison management that added hard labour to the Philadelphia System of solitary, penitence and prayer. His photobook Songs of a Silent Wall brings together archive images of American prisons.

Librandi-Cowan has contempt for the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) in the United States and the manner in which its decentralized and embedded nature allows for its silent persistence. His work mounts a narrative that writes Auburn into the early chapters of the development of the PIC. It’s not a narrative closely examined by others in his hometown. Shaping and presenting the work has not been without its challenges.

It is Librandi-Cowan’s negotiations between critiquing the system and maintaining empathy for ordinary people who work in it–who are also swallowed by it–that fascinate me. Not least, because other image-makers focused on prisons are dealing with similarly delicate negotiations.

I’m grateful to Librandi-Cowan for making time to answer my questions.

Scroll on for our Q&A.

Q&A

PP: How did your work on Auburn Prison come about? Is it still ongoing?

JLC: The project formed into the focus of my undergraduate studies and eventually into my thesis work. The project is ongoing. The work requires a slow, long-term approach. While Auburn is my hometown, I still struggle to understand and represent it visually. My relationship to Auburn, much like the town’s relationship to the prison industry, is complex. I critique and question the history of an institution that has almost always supported the community. The fact that I am a member of the community, forces me to move slowly and carefully.

The history takes a while to sift through, the relationships I make with fellow Auburnians take a while to forge, and figuring out how to represent and combat the prison industrial complex isn’t something that is simple to figure out.

PP: When did you first start thinking of the prison as a topic for your art and inquiry?

JLC: The prison sits in the middle of the city. Many members of local families, generations deep, have been employed by the prison industry. Growing up, I was vaguely aware that some of my family had worked in the prison, but I never gave the prison – which was down the street from where I lived, always in view – much of a thought.

I knew little bits about the prison’s history – that it was one of the oldest prisons in New York State, and that it was the first place to host an execution by electrocution – but the prison, and ideas related to imprisonment, were seldom discussed or explained. I never questioned or understood the prison beyond it being a place for employment.

It took me a while to realize that it wasn’t necessarily normal to have a prison down the street or to have a family member or neighbor that worked inside a prison.

JLC: As I got older, I began to learn more about the prison system, mass incarceration, the economics involved and I began to realize that the prison had a much larger influence on my community than I had initially thought or understood. I began making images to make sense of the complicated role the prison has had with my hometown, with history, and with myself as a young person living in the town. I began photographing in an attempt to make sense of the prison system from the lens of a prison host community, but immediately I realized that it further pushed me to question it.

PP: Where have you presented this work?

JLC: I have presented this at the Cayuga Museum of History and Art, which is Auburn’s local history museum. I have also shown selections of the work at LightWork in Syracuse, NY, and I recently opened a show at SUNY Onondaga.

PP: When you showed it in Auburn itself how was it received?

JLC: Reactions varied – it was positive, negative, and also a bit static/unresponsive. Much of the feedback I received were initial aesthetic responses, and not feedback on the conceptual aspects or questions the work asked.

The prison is a top employer within the community, so people are seemingly reluctant to critique or question the role of the prison, its historical implications, or what the hosting of a prison means for a community.

While showing the work in Auburn, I made it clear within my presentation that I was questioning Auburn’s role within the prison industrial complex – past and present – and that I was interested in finding a way within our community to talk about the increasing problem of mass incarceration within the United States.

JLC: I found this information to be much more difficult to present and discuss within Auburn because so many within my community are directly involved with the correctional system. It was incredibly difficult to find ways to talk about what the work questions without the perception that I was criticizing the generations of people within my community who work or have worked at the prison. Finding productive ways to critically engage, discuss, and question the livelihood of many in my community has been very difficult.

In turn, the response to the work often ends up being extremely limited. Employee contracts won’t allow for correctional officers to discuss some of these issues with me, nor they do not want to talk ill of their work. Many people within my community have a difficult time reasoning with my questioning of the prison system; their relationships to it are complex, deep, and difficult to reckon with.

While many may generally agree that the prison system doesn’t function properly or fairly, Auburn’s relationship to its prison doesn’t seem to allow for a communal discussion on the matter.

PP: You suggested to me in an email that your worry over local reactions have effected the way you edit and present?

JLC: I wouldn’t say that I’ve necessarily changed the work, but I often worry that the project, and that the directness of my stance on the prison industry, may do damage to my community – especially when presented internally. Auburn has bore witness to much trauma. It has direct and early links to the Prison Industrial Complex, the electric chair, and to correctional practices that have helped shaped modern day incarceration. Condensing and presenting that information to the community almost produces and perpetuates this trauma. While it’s not the community’s direct fault, my questioning of these practices and histories has the potential to produce the feeling that the community itself is to blame.

While it is important to combat mass incarceration and the toxic attitudes that prison work can breed, I believe it’s also important to realize and remember that prisons have direct effects on the people who work within them and on the communities that host them.

To me, the ability of many within my community to navigate between the daily entrapment of prison walls and civilian life, begins to raise many questions about how traumas and toxic attitudes are transferred and perpetuated within my community and within society in general.

JLC: Prisons not only affect incarcerated individuals – they affect those who staff the prisons, the people close to those staff too. They affect towns that host prisons and communities from which members are extracted to then be incarcerated.

Prisons shape, and are shaped, by local and regional economies connected to the prison industry, and attitudes towards race – the list goes on. I’m trying to show that the web of the prison industrial complex, while much closer to my hometown than others, is something, often almost invisible, that is local to almost every American.

While I doubt many would pick prison work as their first employment opportunity, it is one of the only financially stable options within the Auburn area. Attacking the industry that financially provides for many within the community doesn’t seem to be the best way to have these conversations or to figure out alternatives or answers to the prison.

As I continue this project, I am attempting to find ways to properly and effectively critique mass incarceration and the Prison Industrial Complex without alienating or further damaging my subjects – whether they be community members, correctional officers, or incarcerated individuals, or returning citizens.

PP: What is gained and what is lost by such slow and reflexive approach?

JLC: Being cautious and thoughtful about how the work may impact the actual people that the work represents will only help further the project and its possible impacts.

Much of the contemporary work on prisons deals with incarcerated individuals, however, I’m becoming increasingly interested in figuring out how conversations and representations of others within the prison industrial complex can impact and change our discussions on mass incarceration. Maybe if it can be shown that mass incarceration negativity effects all within the equation, different sources of change may occur?

I believe The Auburn System functions well outside of Auburn because distance from the work allows for a more general discussion around mass incarceration. But showing the work within Auburn has made me rethink how it should function within the town.

PP: Thanks, Joe

JLC: Thank you, Pete

–

JOE LIBRANDI-COWAN

Follow Librandi-Cowan‘s work on Instagram, VSCO, Facebook, Vimeo, Tumblr and Twitter.

‘Chasing the Dragon’ © Robert Saltzman / Juan Archuleta. From the series “La Pinta: Doing Time in Santa Fe”

–

I’ve heard from a couple of folk that when I started Prison Photography, they laughed at its folly. Not only had a bleeding-heart liberal thug-hugger come along to explain a world no-one cared about to no-one in particular, but silly-little-leftie-me would run out of projects and photographs in no time. Not only had I picked a subject nobody cared for, I’d neglected to do the proper amount of research and maths.

Well, more than eight years later, and I’m still stumbling upon scintillating projects that challenge my ever-evolving timeline of prison-based visual arts. Case in point La Pinta: Doing Time in Santa Fe, a collaboration between Robert Saltzman and the prisoners of New Mexico State Penitentiary, in Santa Fe, NM.

© Robert Saltzman / Keith Baker. From the series “La Pinta: Doing Time in Santa Fe”

Saltzman first visited the prison in 1982 to visit a friend and thereafter was fascinated by the lives behind the walls. Despite a massive riot less than two years prior, Saltzman convinced the warden to allow him in with his 35mm SLR, three lenses and camera-mounted flash. Saltzman gave assurances he was there as an artist and not as a reporter.

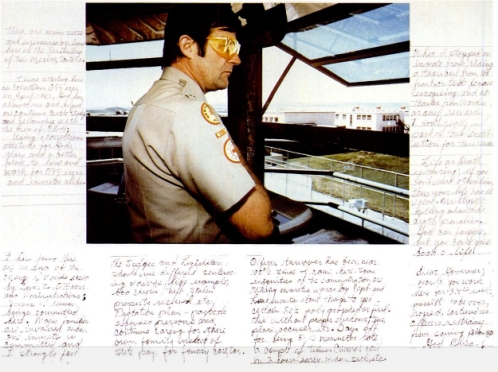

Over 9 months, Saltzman made 500 images on Kodachrome64 film. He picked the 35 strongest portraits but still wasn’t happy. They failed to tell a fraction of the stories or reflect even a small slice of the range of emotions he encountered. So he printed the 35 out and mounted them on white illustration board. He sent them back in, a few at a time, with a request.

“Please use the white space however you want,” Saltzman told Popular Photography in 1985.

© Robert Saltzman / Jonathan S. Shaw. From the series “La Pinta: Doing Time in Santa Fe”. Screengrab from Google Books scan of an issue of Popular Photography (Vol. 92, No. 3, March 1985, pages 66-69 + 141, ISSN 1542-0337)

Some photographers would be happy to get in and out with some portraits and call it a day. Plaudits to Saltzman that he distanced himself enough to make a hard call about the nature of his pictures. And with it adding more time and uncertainty to the project.

28 total works came back. In the first exhibition of La Pinta: Doing Time in Santa Fe, 11 were shown. Later, 14 were exhibited.

“The drawings and writings, coupled with Saltzman’s portraits, communicate a poignant and often tension-filled commentary on the prison experience,” writes James Hugunin, art historian, expert on prison imagery and curator of a 1996 show Discipline and Photograph which included Saltzman’s work.

© Robert Saltzman / Ralph K Millam. From the series “La Pinta: Doing Time in Santa Fe”. Screengrab from Google Books scan of an issue of Popular Photography (Vol. 92, No. 3, March 1985, pages 66-69 + 141, ISSN 1542-0337)

This work excites me because it avoids easy categorisation. This type of collaborative work is standard-fare these days with a new generation of practitioners inspired by the social justice priorities of photographers like Wendy Ewald, Anthony Luvera, Eric Gottesman and many more. In the early eighties however, when Saltzman et al. made these, collaboration was considered a bit amateurish. God forbid you allow scrawls upon photographs! Pencil was meant only for contact sheets, editing and for marking crops for the darkroom. Note that among famous photographers Robert Frank made some good scrawls on his stuff in the 70s for himself and for ad campaigns in the 80s and we all know Jim Goldberg’s Rich and Poor (1977-78) was before its time and the high-profile example of a photographer handing over prints for subjects to write upon.

With the exception of Danny Lyon, all the photographers I know that preceded Robert Saltzman in photographing inside US prisons–Steven Malinowski, Gary Walrath, Joshua Freiwald, Sean Kernan, Cornell Capa, Ruth Morgan, Douglas Kent Hall, Taro Yamasaki–were invested in keeping the camera, and thus the message and interpretation, in their own hands. Given the times and the preciousness of access, it makes sense that photographers would internalise society’s general attitude toward them as special messengers. (I should flag here, as I always do, that Ethan Hoffman’s work and book Concrete Mama was exemplary of this time in terms of giving over great space for his imprisoned subjects recount their stories.)

I wouldn’t say that photographing prison guards hadn’t happened by the early eighties, but it was unusual. So for Saltzman to get the written reflections of guard Ralph K. Millam (above) is significant too. Most photography projects within prison focus on the prisoners and very few focus on both the kept and the keepers.

In short, due to both its subject matter and approach, Saltzman’s La Pinta is landmark. Prisons weren’t photographed much in the early eighties and certainly not for as long as a year, the time it took Saltzman to complete the work. Its collaborative methodology allows for heightened emotional impact and positions it ahead of other works that later used similar formulas and embodied likeminded sympathies.

See more here.

Hospital lobby. © Kim Rushing

–

Long before I started writing about prison imagery and before I even set foot in the United States, photographer and educator Kim Rushing was making images of the men at the infamous Parchman Farm, known officially as Mississippi State Penitentiary. Rushing made these photographs and others over a four year period (1994-1998). They recently been published by University Press of Mississippi as a book simply titled Parchman.

After a first glance at the photographs I was surprised to hear they were made in the nineties. Many images appear as if they could have been captured in much earlier decades, but such is the nature of prisons which either change at glacial pace or remain in a temporal stasis–uniforms replace identifiable fashion; hardware is from eras past; conditions can appear mid-century; and the vats of the kitchens and gas chamber seem permanently footed to the concrete foundations.

Spaghetti, central kitchen. © Kim Rushing

Gas chamber. © Kim Rushing

Rushing’s photographs are a welcome view to a past era and a brief step back in time. My overriding takeaway from the project is that time, as in all prisons, operates by its own rules.

Rushing’s contribution to the emerging visual history of American incarceration is valuable, not least because it contains some hope. Whether the absence of violence is a fair reflection of Parchman would be a worthwhile discussion but for broader research some other time. Take the images at their face value and we can identify other prevalent characteristics of prisons, namely boredom, containment, some programming, and certain longing. (I’d hazard to guess the programming such as gardening have been scaled back.)

To insist that an almost predictable perspective on prisons exists in Rushing’s work is borne out in close comparison of the work of other photographers. Rushing’s portraits are very similar to those of Adam Shemper’s made at Angola Prison, Louisiana in 2000.

Cornelius Carroll © Kim Rushing

There are also quiet echoes of David Simonton’s 4×5 photographs of Polk Youth Facility in North Carolina made in the nineties. Except in Rushing’s images prisoners inhabit the scratched, peeling interiors. Interestingly, both bodies of work remind me of Roger Ballen‘s dark worlds, but that might be a leap too far given the specific psychological manipulations by Ballen in his native South Africa.

Gregory Applewhite at window © Kim Rushing

In terms of touchstone and stated portraiture projects, I see fair comparisons with the incredible work of Ruth Morgan in San Quentin Prison, California made in the early eighties.

Billy Wallace. © Kim Rushing

And in terms of predictable moments, I cannot help but think of Ken Light’s portrait of Cameron Todd Willingham in Texas from 1994, when I view Rushing’s photo of Kevin Pack (below).

Kevin Pack watching TV. © Kim Rushing

In the book Parchman, alongside Rushing’s images are the handwritten letters of 18 prisoners–ranging in custody level from trustee to death row–who volunteered to be photographed. “What does it feel like when two people from completely different worlds look at each other over the top of a camera?” asks University Press of Mississippi. In this case, I’d argue, the successful insertion of humanity into an institution that has historically crushed the spirits of those inside. Clearly adept in his art, Rushing has made a stark and sometimes touching portrait of an invisible population.

Feeding the spider © Kim Rushing

–

Parchman (cloth-bound; 10 x 10 inches; 208 pages; 125 B&W photographs) is now available for $50.00 from University Press of Mississippi.

My latest for Vantage:

When Stockton filed for bankruptcy in 2012, it was the largest city in US history to do so. Kirk Crippens has spent the past three years photographing its residents.

It seems unlikely Kirk Crippens’ portraits are really going to affect the lives of the residents of Stockton, California. It is their portraits that make up his series Bank Rupture. Rather, it will be food banks, loan relief, and Stockton’s fiscal restructuring that will deliver much more direct — negative and positive — effects.

Grand statements and big claims aren’t Crippens’ style. Modest and curious, Crippens uses image-making to investigate and connect with the world. He photographs to establish relationships beyond his immediate working and daily experience. It might sound trite, but Crippens employs photography to show he cares. Having interviewed Crippens numerous times I’m confident in the claim.

“I served as witness. I immersed myself for a time and took some photographs along the way,” says Crippens.

Read the full piece and see a larger selection of images larger.

WHERE IS THE REFUGE IN A PRISON?

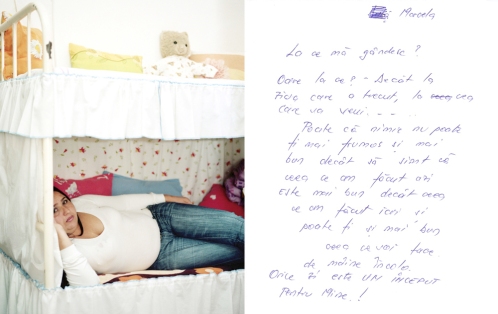

Where is our greatest refuge? A hideaway? Our home? The bedroom? The bed? Artist Dani Gherca reasoned that for women imprisoned in her home country of Romania, the greatest refuge was the bed.

“The bed is no only an object used for the body’s physiological and physical rest, but it’s also an intimate space for the women during the detention. The two square meters around the bed, is the only perimeter she can keep for herself,” says Gherca. “After I talked with some prisoners, I found that, in the evening, when the lights go out in the detention room … that is the only moment when each one of them can afford a really intimate moment.”

As such, Gherca made portraits of women on their beds and asked each to provide context by asking them about their thoughts during those quiet, solitary minutes. The resulting series is called Intime (2012).

I asked Gherca a few questions to provide background to Intime. We publish the female prisoners’ responses in full.

Please continue scrolling.

–

Alina

The night-my thoughts. The night for me, as well for the people around, represents the most quiet period, in which the soul and the mind can meditate and can realize what they’ we done bad or good during the day. The night behind bars is both sweet and bitter. The loneliness oppresses me, the distance from my family struggles me. Every night I am thinking about my child that I love and respect with all my heart; at the beautiful moments that I lost because of my mistakes. I am thinking at the moment when I will step over the threshold to freedom; at my little’s girl innocent smile and sweet hug. Every night I pray to be strong to carry out the punishment and to can be next to my child and to make it up to the period in which she stayed without me.

–

Q&A WITH DANI GHERCA

Prison Photography (PP): I understand the method, the aim and the outcomes of Intime, but why did you want to photograph inside a prison in the first place?

Dani Gherca (DG): The idea of intimacy is very important for me. I think that us, as human beings, we need freedom of mobility, but have also the bigger need to be able to decide when we want to be alone. The prison is an institution that hides people’s need of intimacy, an institution that limits the woman’s need for mobility.

PP: Targsor has been photographed before – in a photo workshop format by Cosmin Bumbut and by photographer Ioana Carlig. Were you aware of these projects?

DG: Yes, I know Cosmin and Ioana’s projects. However, I am interested to document the prison only on the conflict between privacy and this space that compels people to live together 24 hours a day.

PP: Has Targsor been photographed so much because it is relatively relaxed?

DG: Targsor Prison has a more permissive status in this kind of approach. However, I was attracted by this prison because it is the only prison for woman from Romania.

PP: What do Romanians think about prisons?

DG: In the last 3 years, the prison has become an institution that is seen as a method of revenge, mainly due to politicians who were sentenced in large numbers in this period.

PP: What do audiences think about your portraits and the prisoners’ written thoughts?

DG: The audience was more interested in the letters written by the girls. It was a new situation: to have access at the thoughts of some prisoners. Given the fact that this wasn’t an interview, the girls were more relaxed, and acted like they had written letters.

PP: Did the women talk about photography and what it gave them? Did for them? How they used it?

DG: I took them some printed photos. They send pictures home so it’s a good opportunity for them to have some portraits to send to their families. Otherwise, they cannot take pictures. Generally, I think they like to pose. It makes them feel somehow important.

PP: Thanks, Dani.

DG: Thank you, Pete.

–

WOMENS’ TESTIMONIES

Ana Maria

“Of all the moderates, the most detestable is the one of the heart.” (A. Camus)

Of how much love we gathered in my soul for you, I’d be able to build the whole world and would still remain. I could build seas and oceans, the sky with billiards of stars and would still remain because my love for you doesn’t knows limits or dimensions. That’s why, I will take a little piece from my soul and a little from your love and I will build a world JUST FOR US and a sky for OUR stars to shine and an infinite ocean of love in which we can swim after the OUR sun will burn our feet after longs wanderings though cities lost in antiquity, cities of a civilization where we have our roots and have never been known, only by angles because the holy land of our love has its foundation on the last rung of the ladder that climbs to God.

–

Ana-Maria

Before getting here I was very happy next to my children, next to my family. I regret I am sorry that I have to stay away from my family and she suffers too for me. Now I am sitting and thinking at a more beautiful and happy with my family. To find a place to work, to take walks with the children in the park, to build them a beautiful future, to teach them only nice things, to take them to school to stay away from various kinds of crimes. I have an advice for the ones outside, for all the scholars: stay away from the entourages. The entourages will make you steal, rob. They will make you commit various kinds of crimes and is it wrong to get here. Here is a big sufferance and it’s hard to abide, to stay away from your children, from your family, it is very hard. Please think well before getting in entourages and with who will hang out.

–

Claudia

My thoughts. I am thinking every night at my little boy and at my family to arrive as soon as possible next to them at home. Millions of thoughts and ideas that I want to do appear in my mind, but all are in vain, because I am here. I like very much to listen to music and to sit in quiet because I am a calm person. I am waiting forward for the day when I will be at home. This is the only thing that I am thinking about.

–

Gica Claudia

My thoughts. I am thinking every night about how I will retake my life back into a new beginning, a new life. It’s hard and very hard to retake it from the ground, but with the help of the Good God, I will succeed with everything that I passed by sufferance. I have 3 children and I am thinking every night at them and at their future, do not go through what I went through in life. Another life for them, the very best.

–

Isaura

At night I am thinking about; my family, at the liberation, at what work place to find, night by night. I regret the day when I committed this crime, and I am thinking how to build my life so I won’t get here again, because it is very difficult to think that there is nothing more valuable than freedom.

–

Marcela

What I’m thinking? Really, what I’m thinking? Only about the day that passed, and the day that will come…

Maybe nothing can be more beautiful and more good than to feel that what I’ve done today is better than what I did yesterday and tomorrow I will start something better. Any day is A BEGINNING for me!

–

Monica Luminita

My thoughts. I am thinking every night when I sit in my bed about my children and at how I will react after four years have passed day-by-day. I like listening oriental music. I like Turkish movies, the comedies.

At night, I have moments in which I can’t sleep because of the punishment and I am thinking from where I started and where I’ll finish at my day of freedom; when I will see my children after 4 years and a few months. I repent for getting in these places. Never in my life I will I commit crimes, to arrive here again. I won’t leave my children alone ever.

–

BIOGRAPHY

Dani Gherca (b.1988) lives in Bucharest and works in Romania. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from the Photo-Video Department, at the National University of Arts in Bucharest (2013) and a Masters of Arts from the Dynamic Image and Photography Department, at the National University of Arts in Bucharest (2015).

In the past when I have discussed prison Polaroids, I have said they are perhaps one of the more significant subsets of American vernacular photography, and that they are not easily found online and that, due to their absence, our perception of prisons and prison life continues to be skewed.

Well, times change and that position now deserves correction. I have noticed a few collections coming online recently. Not least the Polaroids from Susanville Prison on the These Americans website. (Also, check out the new PRISON subsection of the site.)

Online, I have identified some increase in the number of contemporary prison visiting room portraits and, as in the case of These Americans, collections of older, scanned images.

I would suppose that many Facebook users have scanned visiting room portraits and added them to profiles but, only visible to friends, those social network image files have not been reproduced for public consumption or commentary. We might think of Facebook photos and albums as digital versions of the mantlepiece, i.e. seen only by close friends and family.

ONGOING FOCUS

“Prisoner-complicit” portraits (for want of a better term) are taking up a lot of my thoughts currently.

Yesterday, I had a workshop with the #PICBOD students at Coventry University, in which I assigned readings on Alyse Emdur’s visiting room portrait collection, prison cell phones as contraband, prison cell phone imagery as cultural product, a new Tumblr In Duplo that compares publicly available mugshots with publicly available Facebook profile pictures, and the racket that underpins the posting and removal of mugshots to the searchable web.

Particularly with cell-block-cell-phone images, we should anticipate a glut of prisoner-complicit photos in which prisoners – to a greater degree – self represent.

We should realise that this is the first time in modern history that prisoners have presented themselves to the internet and thus permanently to the digital networks of the globe. My hunch is that this may be significant, but really, it’s too early to tell.

We can note that in this video, most of the images seem to originate from the same cell phone camera in the same prison. We might surmise there is no epidemic of illicit and smuggled images yet. To further this inquiry, I hope to get some information from the maker of said video.

In the mean time, I’ve been in touch with Doug Rickard who administers These Americans as well as the wonder-site American Suburb X. I asked him about his recently published Susanville Prison Polaroids:

Any idea who took them? (any marks/prison-stamps on verso?)

Probably a visitor or another inmate? I have a set (10 or so) of the main inmate (“Johnny”) that you see in many of the “Susanville” single poses, posed with “Brown Sugar” (his girlfriend/wife) and his son “Champ”, a boy that grows from 1-3 years old in the various pictures (see below).

What years do you think they span?

I can only find one date, 10-24-80. You would think that they were 90’s, but for sure, it says 80.

What makes this collection so fascinating to me is that the operator(s) appears to have had free reign of cells, tiers and the yard to make these single and group portraits. One of the PICBOD students at Coventry today wondered where their supply of Polaroid film came and then to where the images were eventually dispersed outside the prison.

We could only conclude that this prisoner and his group of friends had special privileges and access. From all of my research into (vernacular) prison photography – specifically prisoner-made photography – this sort of arrangement/privilege does not exist in American prisons today.

MORE ON THESE AMERICANS

http://www.theseamericans.com/media/minnesota-mugshots/

http://www.theseamericans.com/prison/last-prisoners-leave-alcatraz-1963/

http://www.theseamericans.com/prison/visiting-hours/

http://www.theseamericans.com/prison/prison-collection-%e2%80%9cjoliet-state-prison%e2%80%9d-1963/

http://www.theseamericans.com/prison/florida-collection-jack-spottswood-sunbeam-prison-camp-1950/

http://www.theseamericans.com/prison/california-collection-san-quentin-prison-1925-1935/

http://www.theseamericans.com/prison/polaroid-collection-mcneil-island-prison-wa-1970s/

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Thanks to Peg Amison for the tip.

Natasha, Women’s Prison, 2009. © Michal Chelbin

For the past three years, Michal Chelbin has made portraits in the prisons of Russia and Ukraine. You can see a selection of the works from her series Locked on the New Yorker Photobooth blog.

Chelbin’s doleful portraits are striking – something different – and, of course, given their subject matter I was compelled to mention them here. However, without any specialist knowledge of the prisons in Russia and Ukraine, I struggled to think of a worthwhile statement to accompany with them. Is it enough for me just to say that work is beautiful and interesting? I don’t think so.

Therefore, this conundrum becomes the focus of this short post.

The way Chelbin describes it, her portraits are the first step on a journey (of undetermined length) to at least attempt to “know” her subjects:

“When I record a scene, my aim is to create a mixture of plain information and riddles, so that not everything is resolved in the image. Who is this person? Why is he dressed like this? What does it mean to be locked up? Is it a human act? Is it fair? Do we punish him with our eyes? Can we guess what a person’s crime is just by looking at his portrait? Is it human to be weak and murderous at the same time? My intentions are to confuse the viewer and to confront him with these questions, which are the same questions with which I myself still struggle.”

It seems to me that this the type of curiosity we should expect of all photographers and their works; it’s partly how we are drawn into the previously unknown.

But the unknown has its dangers. As Fred Ritchin stated:

“Photography too often confirms preconceptions and distances the reader from more nuanced realities. The people in the frame are often depicted as too foreign, too exotic, or simply too different to be easily understood.”

Beautiful photography is easy to come by these days, and so, for me at least, viewing beguiling portraiture becomes an act of enjoying the beauty but then stepping further and using it to get at something deeper. That might involve a dialogue with someone over coffee; it might be to find comparative examples [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]; it might be to read up on the conditions for juvenile prisoners in Russian prisons; it might be to read the photographer’s statement or even contact the photographer directly to seek the missing pieces.

Photographs, and particularly portraits, are often a door unlocked but often in our busy lives we don’t even try the handle.

Perhaps now is a good time to return to some thoughts on what makes a great portrait, here and here.