You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘UK’ tag.

‘OPERATION JURASSIC’ BY PABLO AND ROXANA ALLISON

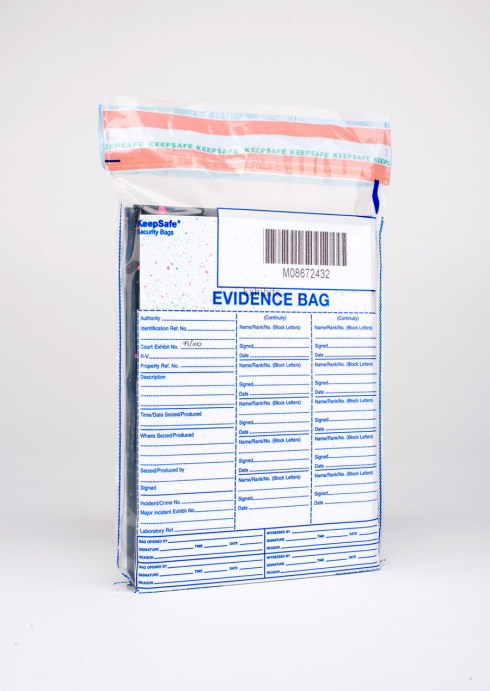

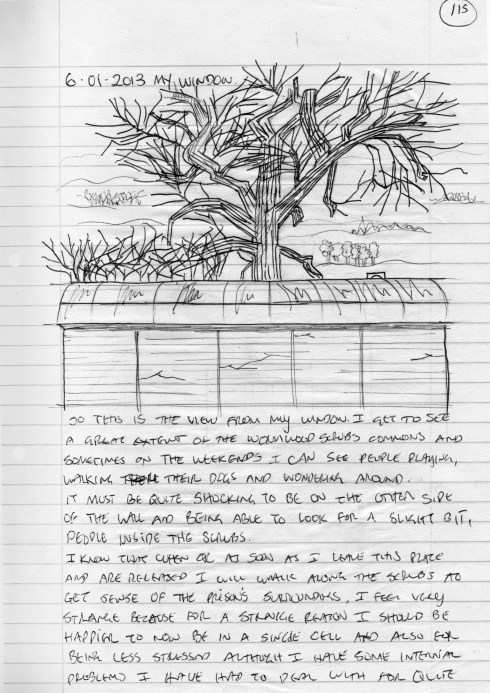

Brother and sister Pablo and Roxana Allison were separated for five-and-a-half months from late 2012 through spring of 2013. Pablo was locked up in London for criminal damage after being prosecuted for graffiti writing on trains. Pablo was one of several defendants sentenced as a result of Operation Jurassic, one the UK’s largest cases brought against artists using train carriages as their canvas. Since, the siblings have worked on putting together a visual record of the time and their emotions. The resulting book Operation Jurassic, published by Pavement Studios, just hit the stands. I wrote an introductory essay which I am pleased to republish here.

Scroll on!

A WARM THREAD

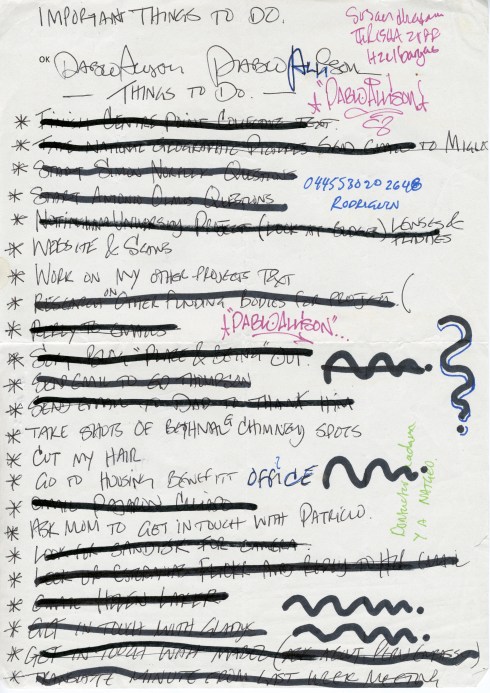

This book is a thread. A warm thread spun by two siblings during one’s incarceration. These images, conceived during months of separation and crafted during more months of house arrest, emerge from the worry and dislocation imprisonment brings. Born of necessity, these images are what Pablo and Roxana Allison did, dreamt up and fabricated; emotional twine that kept them sane and connected both.

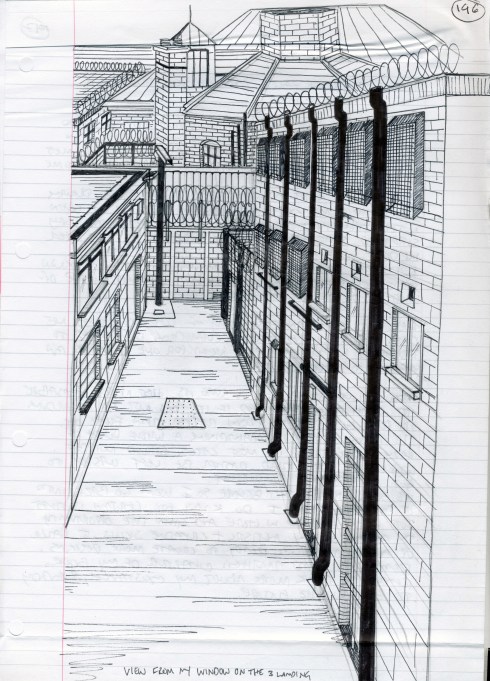

As one in a cohort of graf-writers targeted by Operation Jurassic and done on charges of conspiracy and criminal damage, Pablo saw his conviction coming. It was likely he’d get a custodial sentence. Prior to the trial, he and Roxana decided that images could graft the space between them. He’d draw and describe scenes inside prison while she’d document her isolation at home. They’d plan photo-shoots for when he got out to capture what he couldn’t while inside. For painting trains, Pablo was locked up in November 2012. Roxana, while not entirely sympathetic toward his graffiti at that time, was horrified that he’d get sent down for his art. Together they resolved to come through it with a visual record. He served 5-and-a-half months in Wormwood Scrubs and HMP Brixton followed by one year, at home, under curfew with an electronic monitor strapped to his ankle.

This book is woven through with detachment. Doleful figures cut lonesome shapes—veiled, obscured, there but barely there. Sometimes only a shadow. Interior details and still-lives serve as descriptors of halted lives. Scratched through with twilight, bisected by lines and tree limbs, these photographs edge toward a shared emotional territory, but they’re only placeholders of time lost. In that way, they double as evidence of Pablo and Roxana’s defiance. From a position of near zero control, they intended to shape an outcome. These images establish their testimony in spite of, and in challenge to, the court proceedings, prosecution arguments and criminal narratives of British Transport Police (BTP) and the presiding judge. A warm, human thread of struggle spun from the dehumanising reaches of prison and house arrest.

Initiated in 2003, Operation Jurassic was one the largest prosecution cases ever brought against graffiti artists in the United Kingdom. Pablo and nine others were arrested in 2010. Pablo was one of five who consequently, in November 2012, faced trial for criminal acts perpetrated between 2005 and 2009. At the outset, the prosecution detailed upward of $10 million in damaged infrastructure but at trial only made a case for $1 million worth.

Potential punishments for graffiti-related crime in the UK is high. The BTP “Graffiti Squad” went after eight members of the DPM crew with Operation Shuttle, and in 2008 secured jail sentences of 12 to 24 months for all. In terms of the cost of the operation (£1 million to the taxpayer) and convictions (imprisonment), Shuttle set precedents of which Pablo and his cohorts later bore the brunt. All for putting some paint on some surfaces.

Led by Detective Constable Colin Saysell, the BTP Graffiti Squad went to war on graf-writers. During his 30-years as a copper, Saysell has helped convict 300 artists. Including Pablo. But his exacting approach is out of step with the British public who laud mainstreamed graffiti artists such as Banksy and Ben Eine. (Famously, in 2010, David Cameron gave Barack Obama a Ben Eine piece as a diplomatic gift.) Compared with law enforcement agencies abroad that don’t imprison graffiti artists, Saysell is an extremist.

Furthermore, compared to public education and youth outreach, Saysell’s hardline stance is bizarrely contradictory; murals and tags are used as an art-medium with which to engage city-kids’ creativity. A charity once took a double-decker bus into Wormwood Scrubs where members of the DPM crew painted it! Roxana wasn’t the only one staggered by Pablo’s imprisonment. Guards and prisoners alike couldn’t believe that, for making art, he was banged up alongside men who had murdered and maimed.

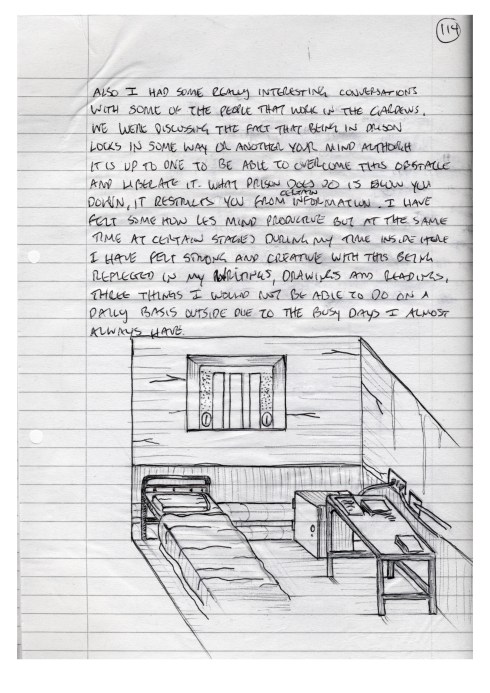

“Have you met any killers yet?” asks Antonio Olmos, photographer and mentor, in a letter to Pablo. “Anyone interesting like a member of Al Qaida or a dress designer? I imagine a lot of creative people are in prison…” On the inside, Pablo’s monochromatic, A4-sized sketches and notes are a far cry from his hulking, clacking train-car surfaces on the outside, where he would stalk yards for days in preparation for a night of painting.

Once inside, Pablo experienced a shift in his creativity. He felt his mind slow and the down-tempo pace worked because apart from writing and drawing he had little else to do. Time was spent on mailed offerings to friends and family. It’s almost too obvious to state that letters are lifelines for prisoners, but this book is built on the insistence of connections maintained, feelings felt and testimony spoken.

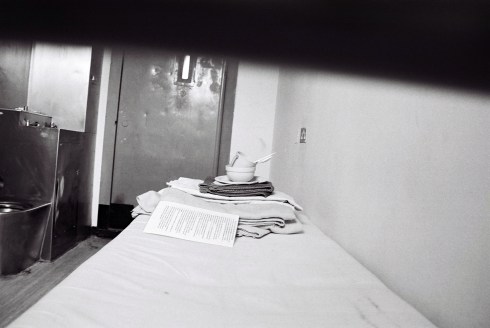

In this book, time and space are deliberately confused. Pablo is behind bars and then half-submerged in the Pacific Ocean. A prison sits in mid-winter and then, pages later, peeks from behind the full foliage of mid-summer. Some images reconstruct the confines of cell. Another the view from the back of a “sweat-box” custody van—a photograph that could never be made. Pictures of held hands and tired glances might be from before sentencing, or from the visiting room, or made during post-release house arrest. We have entered a chronological fog that mirrors the emotional fog endured by Pablo, Roxana and their family.

Photos of actual prison cells exist too, but how can that be? Pablo did have a camera in Wormwood Scrubs but not during his time as prisoner. In 2005, at the request of a local council member, a teacher from Hackney Community College asked Pablo and fellow students to visit the famous prison and make images for Prison Me, No Way!, a deterrent program designed to show young people crime’s causes and penalties. (Ironically, the British Transport Police is a partner of Prison Me, No Way!) Pablo kept those images, but never imagined he’d revisit the canteen, cells and tiers as an inmate. In these pages, site and sights (spaces and time) loop back on one another; exile has its own haunting feedback.

The pages of Operation Jurassic seem drained of blood. Understandably so. Roxana and Pablo’s lives were gutted to a great degree. Photographs flatten the world. Two dimensions tend to fail the fullness of life. Frustrated acceptance and silent screams run through these images. In some ways it is remarkable that Pablo and Roxana even wanted to return to their anemic limbo, let alone depict it.

These photos, legal documents, letters, emails, drawings and diary extracts bottle the soup of inconvenient memories that Pablo and Roxana cannot leave behind, nor that they want extinguished. From raw emotion and these memories, they grew. Despite the grey spectre of institutional control and despite the slowed pulse of the carceral clock, this book is Pablo and Roxana back in control. It is a warm thread. It is a gift too. Imagination and pictures, letters and sketches were what they had. Now, it is what we have.

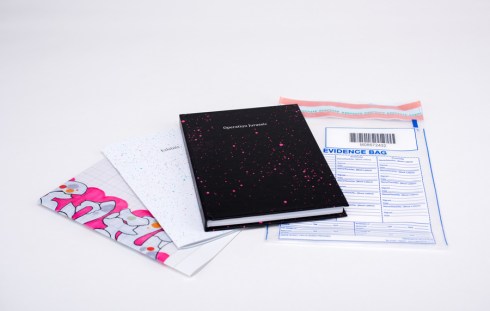

Operation Jurassic

Pack includes:

100 page A5 Hardcover Book

36 page Staple-bound Zine

A3 Double-sided folded Poster

1st Edition of 100 copies. All books hand finished.

Follow Pablo on Instagram and Roxana on Instagram. Take a peek at Pavement Studios‘ website and peep them on Tumblr and Instah too.

2041

HERE PRESS has done it again; it has produced a book that allows us an irresistible glimpse into foreign space and psychology. 2041 is a collection of self-portraits, made by a man, donning makeshift burqas and niqabs, in his home in England.

The title 2041 refers to the name by which the man is known. “2041” made thousands of images with the express intent to share them online with fellow full-coverage enthusiasts.

“Using the camera to articulate a passion he has secretly indulged for decades, the artist appears dozens of times without ever disclosing his image or identity,” says the HERE press release. “Long before 2041 bought his first real burqa online, he began crafting his own versions from draped and folded fabrics in a rich array of textures and colours … ranging from the traditional to the theatrical.”

2041 is part of a connected online community of men and women from across Western Europe and the Gulf States. They are Christians, Muslims and without religion.

This is a gripping book and look into a world that cannot be fully known, nor can be fully verified. What is interesting, therefore, is that without identifiable subjects, the veracity of photography collapses. Or, at the least, we have to completely shift our expectations about what photography provides. The book 2041 is working on, and with, many levels. There’s a motivation by HERE to celebrate photography by revealing its limits and capacity. Despite a reliance on images to connect themselves, 2041 and his cohorts are inhabiting the unphotographable.

As such, 2041 is a playful but earnest exposé of the photographic medium as much as it is this small web of like-minded folks.

A similar type of mood persists in previous titles by HERE. Harry Hardie and Ben Weaver skirt the outer territories of our photo-landscape and delineate the edges. Edmund Clark’s Control Order House took us inside the ordinary domestic spaces of a terror suspect under house arrest. Power was described precisely by what was not photographed. Jason Lazarus’ Nirvana took us into grunge-infused personal histories; the photographs were just a foil to get subjects feting up about beautiful and traumatic pasts.

I, for one, am getting quite excited by HERE’s growing catalogue of ever-so-slightly-disconcerting photobooks.

Between the internet and the veil 2041’s anonymity folds and billows. He remembers the enveloping cassocks and cottas he wore as a choirboy. As an adult, he moved toward total covering. In the early millennium, 2041 his bought his first computer and plugged into an online community that shared his passion.

“What almost all [of the people covering themselves] seem to crave is transcendence of the physical self – or at least being judged on the physical – coupled with the excitement of observing the world unseen, safely cocooned in luxuriant fabrics,” says HERE. “This is the burqa seen in a celebratory light.”

Naturally, I have lots of questions so I dropped Harry at HERE PRESS a line. He put me in touch with Lewis Chaplin who is co-founder of Fourteen Nineteen, but more importantly co-editor of 2041.

Scroll down for our Q&A

Q&A

Prison Photography (PP): Where did you first see and hear about 2041’s photographs?

Lewis Chaplin (LC): I first found these images almost four years ago, while researching emergent subcultures of fetishists/obsessives who were finding community and likemindedness through the internet. Many of these people use Flickr in particular to indulge in their private desires, and it was here that I found 2041’s images. I was struck by the rigidity, flatness and compositional skills that his images had. Compared to most who used the image more as a byproduct or vehicle to access their fetishes, 2041’s images seemed more like the images were performed for the camera and the camera only, for the sake of documentation, rather than for anything else.

PP: Is the book 2041 made in collaboration with the subject? If so, how did you make contact, build trust, ensure discretion?

LC: Yes, it is fully collaborative. Contact was made initially by Harry Hardie , who introduced himself as a publisher, and then I was bought into the conversation. I began a regular correspondence with him, which culminated in a face-to-face meeting and then visits to his house, where we collaborated and photographed each other, and I went through his image archives.

PP: Have all the pictures been verified? Can we know it is the same person under the burqas and niqabs in all the pictures? Does verification matter? Is not knowing something in absolute certainty one of the facets of the images and their use?

LC: I can verify 90% of them through their EXIF data, as we have had access to raw camera files. However, it is not necessarily the same person concealed. I think it is this lack of verification that is the titilating point of these images. Beneath the veil, your physical identity shrinks into a few gestures and outlines, and you can take on the form and countenance of another.

Even now there are images which Ben Weaver (HERE PRESS) and I cannot decide whether they depict our protagonist or others. To be certain though – this form of image-making is a firmly social practice, one based around solid online and offline networks. A few images in the book give this away, and were you to find 2041 online you would find images of me concealed, for example.

PP: Why did you want to make this book?

LC: Because I think that unlike many of the images made by people with strange interests on the internet, these images say something very complex about photography. What I like about these images is that there is that they are purely performative gestures – but yet they give nothing away. They reveal the presence of an individual, but not their likeness, or an accurate representation. Something about the concealment of desire, or the hiding of the true likeness of an object in these images actually feels like a very nuanced statement on photography, that at no stage in the process ever actually tries to use the camera to bear any details, or describe anything accurately.

PP: How many potential subjects and/or images did you have to choose from in making the book? What makes 2041’s images special — some aspects of aesthetics, or merely their availability?

LC: It wasn’t so much a matter of choice, more that these images asked for some kind of sequencing and exploring. There is definitely an aesthetic dimension of these images that is appealing – the composition and contrast between flatness and texture, the shapes are unlike others I have seen – and there is also a lot of time and effort that has gone into these. 2041 is also an actor, and a painter. You can see the influence of classical painting on some of his poses and crops. He is also akin to humour and self-deprecation, you can see it sometimes.

PP: 2041 wishes to remain anonymous. Obviously, as the editor, you’re a legitimate proxy to whom I can talk. I want to ask what 2041 thinks of the book?

LC: Let’s ask him once he has seen it!

PP: What do members of the online burqa fetish community think? What do you think they might think?

LC: I don’t think it has made its way through to these channels, but I would hope that what they see here is that we are not trying to ridicule or pass judgement through our scrutiny. This book I hope comes off as a sincere tribute to photography being used in a genuinely interesting way that talks about self-perception, the way images are used on the internet and so many other things, through the prism of a very personal, domestic and specific application of the camera.

PP: Do we understand what the burqa is and what it does?

LC: In these images the burqa, niqab or any other Muslim garment is a means to an end in some way. You can see in some of 2041’s experimentations that it is just about complete coverage through any means. He is not wearing a burqa in most images, in fact. The removal of physical presence is the goal here – it is never about using the burqa in a subversive or political way.

PP: Thanks, Lewis.

LC: Thank you, Pete.

2041, the book

170 x 240mm, 120pp + 6pp insert

72 photographs + 1 illustration

Offset lithoprint on coated & uncoated paper Sewn in sections with loose dust jacket

Foil title

Choice of 3 cover ‘photo insert’ cards

Text, illustration & photographs by 2041

Edited & designed by Lewis Chaplin & Ben Weaver Edition of 500.

When I was growing up, the dad of some kids at my school worked at the local prison. I had no idea what his day-to-day responsibilities were. Still don’t. This despite the fact I’ve since worked with, been on holiday with, and spent many weekends with the brothers and sisters in the family.

I have no idea, if the dad was involved in some extra curricula or fraternal pursuits; I don’t know if he wanted to even hang out with his co-workers outside of the prison. His job was a fact, but an unexplored and little discussed fact in the parish.

I also had no idea that the England Prison Service Football Association (EPSFA) existed. Not until Positive Magazine featured Riccardo Raspa‘s photographs did I learn of this 40-year-old organisation.

These are the best footballers in the country who happen to work as full-time prison guards.

The EPSFA arranges games between it and RAF, Army, and university football teams and other. It is fed by four regional teams made of the prison guards with the silkiest skills. Raspa photographed a single game and also followed one prison officer inside to photograph him at work. As such the information sways between the recreational tone of sport and the more serious business of control and power behind the bars.

Positive Magazine quotes, Michael Hayde, the England Prison Service coach as saying, “If a prisoner finds out what you are involved in and to what level it does make a difference to how they react and treat you.” And I can believe it. Football, particularly in Britain, is the great equaliser. It’s as accessible as chat about the weather or what you had for your dinner last night.

I’m almost inexplicably drawn to this project. The pictures are quite ordinary but they’re shot with care and some respect.

My care is probably due to nostalgia for the smells and sounds of an evening football match in Blighty and the unexpectedness of this project. (This story would never emerge in America).

But also, the prison staff are humanised here. I’ve said many times before that prisons, especially in America, are toxic places and everyone suffers to some degree. Prison staff are derided as second rate cops or, worse still, glorified babysitters. It’s a tough job and the disproportionately high levels of relationship/marriage failure and drug & alcohol abuse among prison employees testifies to that. Yes, there are corrupt officials and yes, abusive state employees are less seen — and possibly even ignored — because of the feared population they work with. That said, we cannot decarcerate and we cannot radically scale back on prisons if we are not focused on alternatives to incarceration. Bile and hatred for a profession will get us nowhere; it will only distract our energies from finding solutions. And that’s coming from someone who is well aware of the messed-up-shit prison guards have done when no-one is watching.

It is precisely because Raspa’s photographs ask us to view prison officers as individuals that I wanted to include it on the blog. It’s a tough proposition in many ways.

Megan Slade, author of the Positive Magazine, article thinks the EPSFA has got short shrift in the media.

“Despite being a national football team,” writes Slade, “little or rather hardly any press has been covered of the EPSFA, whether due to the nature of the profession this team is part of, or perhaps mainstream football leagues overshadow lesser known associations, they seem to go unnoticed.”

This is not surprising. I guess the quality of football is only just a small step above sunday league stuff. The operations of an amateur football team rarely warrant media spotlight — it has to be an exceptional case.

The lack of coverage here is nothing to be surprised or appalled by. In fact, it is wholly consistent with the distribution of everyday prison stories — you know the ones not about escape, riots, celebrity inmates, serial killers or dog-training programs.

All images: Riccardo Raspa.

You can follow Riccardo Raspa through his website, on his Tumblr, and Twitter.

Adrian Clarke‘s portraits of female former prisoners in the UK are up front and honest. The ladies insisted they go on the record and speak openly about their experiences in HMP Low Newton, an unremarkable small prison for women and young offenders in the north of England. Each woman reported only good treatment during their incarceration.

Clarke’s work is not sugar-coated. He doesn’t have the answers and his subjects, some of whom have ongoing drug addiction struggles, are searching for them.

The women – although aware of their tough lives – do not paint themselves as victims. They want to step up and take responsibility but when you’re that far down it takes a Herculean effort to wright the ship.

Low Newton, like all good portrait series, offers insight. But it does not tie the loose ends. I am left to wonder about the different definitions of normalcy we carry in our day today lives and if these women will find their own versions of normalcy and stability.

Mostly, Low Newton deserves attention because it appears to reflect a complete respect between photographer and subject.

Adrian Clarke’s portraits of female former prisoners are in the latest issue of The Paris Review.

UPDATED: SEPT 4TH 2012. 9AM BST

A week after this blog post went to press, the Prison Reform Trust reported that 77 of the 131 prisons in England and Wales held more inmates than stated capacity.

London’s HMP Wandsworth, which is one of the the three prisons in Elphick’s photographs, is the seventh most overcrowded prison in the UK with 1,191 men being held in a facility only designed for 730 men. Wandsworth operates at 163% capacity.

In total, UK prisons hold 7,300 persons more than they were designed for.

– – – – – –

Hugh Elphick is a young British photographer who, in early 2011, took a cool and curious look at London prisons for his undergraduate photography BFA. The series is Inside.

“I wanted to produce images which intrigued more than shocked,” says Elphick. “I discovered how much prisons actually blend into their surroundings and used this blurring the boundaries, with some of the angles I shot.”

In the series of six photos, Elphick shows us the red-brick exteriors of three prisons – Pentonville, Wandsworth and Wormwood Scrubs. Elphick was working close to Wormwood Scrubs and began to wonder about human rights, the acceptability of the prison system, and if prisons work.

“In England, it is not a commonly known fact [that the UK has the second highest rate of incarceration after the U.S. among industrialised nations] and that it is not something that most people worry about,” says Elphick. “It could be argued that there is more concern that prison sentences are not long enough or that there are moral disparities in sentencing. However, this is not to say that there are not a large proportion of people who see the wider picture.”

Elphick’s focus specifically is about the age of these *famous* Victorian prisons. The Victorian era is steeped in imagery of inequality, squalor and hardship for the working classes. For Elphick, there are points of comparison between the class-stratified 19th century and the inequalities of the modern era and especially today in a time of austerity and cuts in services.

“Victorian architecture offers an allegoric association with harsh systems and possibly with periods such as the late 70 early 80’s economic downturn. Such institutional auras, I believe, explore some of the dilemmas and imbalances of our society,” says Elphick. “These prisons show how little progression there has been in the prison system due to confused government policies.”

Much like the approach of German photographer Christiane Feser, Elphick’s interest is in how these large, alien institutions interact visually with nearby residential communities. Unlike in the U.S., the economic fortunes of the nearby communities in the UK are not tied directly to or dependent upon the operation of a prison. These UK prisons are part of the urban puzzle but quite opposite to the prison-towns of central Wyoming or eastern Washington, which come to rely on jobs as traditional agriculture and industry wane. There is not the same attrition and competition in the job market in central London. Prisons in the UK are not perceived of as big business, partly because by comparison to the bloated U.S. prison system, it isn’t.

In fact, Elphick argues that prisons have almost become mundane in UK cities. He writes in his artist statement:

“The fragmentary nature of London’s development, and its destruction in WW2, have meant a breadth of architectural forms have spread into areas surrounding the prisons. The prisons no longer stand as the monolithic symbols of suffering they once did, and have melted into the architecture of our city. They are taken for granted, dismissed”

This is a peculiar paradox to deal with in images; subjects hidden in plain sight.

“I set out to make a graphic and symmetrical set of images and fortunately there were features which allowed me to do this and at the same time inject some curiosity such as the splash of paint, bench or repaired hole,” says Elphick. “The walls are rigid and literal boundaries which can be translated metaphorically and ironically in many ways to question the justice system and inequalities in society.”

– – – –

Inside was exhibited in the three-person show Behind Bars at One & A Half Gallery, London in September, 2011.

Photographer Mark Woods-Nunn and FLACK, a charitable social enterprise which works with homeless people in Cambridge, UK have put together an intriguing project.

Varsity Mag says, “the attachment of beer-cans to assorted lamp-posts is not another example of misguided modern art. A thin sheet of photographic paper was placed in each can, exposed to the world by only a tiny pin-hole, silently and vulnerably capturing an image.”

Good stuff.

Found via British Photographic History Blog.

Strangeways, Manchester, UK. April 1990. Credit: Manchester Evening News

UK PRISONER VOTING RIGHTS

Brendan O’Friel, the governor in charge of Strangeways during 25 days of famous unrest beginning April 1st, 1990 has backed moves to give UK prisoners the vote.

O’Friel says the controversy is being deliberately stirred up for political reasons. He told the Manchester Evening News:

“I think it is a totally sensible thing to give prisoners the right to vote and then encourage them to vote. Whatever those people have done it is a question of trying to make sure that they are going to make a contribution to the community rather than being a drain on it. Anything we can do to encourage them to take responsibility and think positively is a very good thing.”

O’Friel’s view is not the concensus in the UK. In November 2010, The European Court of Human Rights ruled that denying the vote to prisoners was a violation of their human rights.

However, in early February the House of Commons voted overwhelmingly to reject any lifting of the ban, opposing the move by 234 to 22. By doing so they face a class-action lawsuit which could cost the British taxpayer millions in damages for as long as the government denies prisoners their vote.

The ridiculous thing about this is that the figures (approximately 90,000) would barely effect election results. This is expensive folly by Britain’s politicians.

The UK prisoner voting ban has been in place since 1870.

For comparison, The Telegraph reports:

“Many developed countries have some form of prisoner voting including 28 other European nations such as France, Germany and Italy. Russia and Japan exclude all convicted prisoners. Just two states in America allow it while others do not even give the vote back when inmates leave prison. Prisoners can vote in two of seven states in Australia.”

PRISONER VOTING IN AMERICA

In 2010, judges in Washington State found that felon disenfranchisement laws unfairly impacted minorities as they were more likely to be subject to racial inequalities in the application of policing procedure.

From the ever-excellent Prison Law Blog:

“On Sept. 21, the Ninth Circuit heard oral argument in Farrakhan v. Gregoire, an important case that could affect the voting rights of prisoners in Alaska, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, California, Hawaii, and Arizona. Back in January, a split Ninth Circuit panel ruled that, in Washington State, “minorities are more likely than whites to be searched, arrested, detained, and ultimately prosecuted,” and that, because “some people becom[e] felons not just because they have committed a crime, but because of their race, then that felon status cannot, under section 2 of the [Voting Rights Act], disqualify felons from voting.”

Washington State appealed and the discussion is likely to go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

It’s about time both Britain and the U.S. move into the 21st Century. From the Sentencing Law and Policy blog:

“According to a report co-published by Human Rights Watch and The Sentencing Project, a national organization working for a fair and effective criminal justice system, disenfranchisement laws are “a vestige of medieval times when offenders were banished from the community and suffered ‘civil death.’ Brought from Europe to the colonies, these laws gained new political salience at the end the nineteenth century when disgruntled whites in a number of Southern states adopted them and other ostensibly race-neutral voting restrictions in an effort to exclude blacks from the vote.”

For more on prisoner and ex-prisoner disenfranchisement, read Michelle Alexander. She condenses the arguments of her very successful book, The New Jim Crow, here.

STRANGEWAYS ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

Strangeways Riot and Don McPhee

————————————————-

(M.E.N. story found via Jailhouse Lawyer)