You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘London’ tag.

I wrote about the emergence of the Black Power movement in the UK, for Timeline. Specifically, about a small set of images of one protest and associated ephemera:

At the start of the 1970s, the Black Panther movement in the United States was both well established and well organized. It was also well feared by the authorities. By contrast, black activism in the U.K. was young, with barely a toehold on power. The trial of the Mangrove Nine, in 1970, changed all that.

and

According to the National Archives, photographs such as the ones you see here were “used by the police to suggest that key allies of the Black Power movement were implicated in planning and inciting a riot.”

Read more: When cops raided a hip 1970s London cafe, Britain’s Black Power movement rose up

A toilet in an occupied cell on G wing.

Blood stained, scum-stained, litter-strewn, dirty as all hell, hell-hole of a prison. That’s an accurate description of HMP Pentonville based upon 8 images included in a recent report on the infamous Victorian prison in North London.

I’m intrigued by evidentiary photos; I reckon they can often tell us more than an exposé-chasing photographer can. All we know is that employees of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate Of Prisons made these images. They exist for the record and I can only show them here because HMIP puts out its reports online in PDF format and I took a few grabs. Even then, I only came across them because Charlotte Bilby flagged them for me.

Bilby, Reader in Criminology and Faculty Director of Research Ethics Department at Northumbria University, says that she knows not of previous inclusions of photographs in HMIP reports. I don’t either, but UK prisons are not something I’m particularly knowledgeable about.

Let’s say for now that these photos are a new discover, if not a new departure.

The C wing showers.

Area outside J wing.

An empty G wing cell.

I wonder what other government-employee-made and , technically, publicly-available images exist? I wonder if a broader selection of pics would give the British public a deeper understanding of Her Majesty’s prisons and jails?

Also, I hope other prisons aren’t as bad as Pentonville.

Nick Hardwick, Chief Inspector of Prisons said his team found during an unannounced inspection that consditions at HMP Pentonville had deteriorated since its last inspection (2013) when things were bad already. With 1,200 men and young offenders, HMP Pentonville is overcrowded.

“It continues to hold some of the most demanding and needy prisoners and this, combined with a rapid turnover and over 100 new prisoners a week, presents some enormous challenges,” says a report summary. “Continuing high levels of staff sickness and ongoing recruitment problems meant the prison was running below its agreed staffing level and this was having an impact on many areas.”

The changing area in the C wing shower.

A food trolley.

Blood on a bunk bed.

In response, staffing levels have increased and the authorities remain confident in the warden and the leadership of the institution. While, they believe things can improve quickly, they identified many areas for vast improvement.

- most prisoners felt unsafe as levels of violence were much higher than in similar prisons and had almost doubled since the last inspection;

- prisoners struggled to gain daily access to showers and to obtain enough clean clothing, cleaning materials and eating utensils;

- prisoners said drugs were easily available and the positive drug testing rate was high even though too few prisoners were tested;

- the prison remained very overcrowded and the poor physical environment was intensified by some extremely dirty conditions;

- some prisoners spoke about very helpful staff, but most described distant relationships with staff and were frustrated by their inability to get things done;

- too little was being done to meet the needs of the large black and minority ethnic population, disabled prisoners and older prisoners;

- prisoners had little time unlocked with the majority experiencing under six hours out of their cells each day and some as little as one hour;

- the delivery of learning and skills was inadequate and there were not enough education, training or work places for the population;

- acute staff shortages had undermined the delivery of offender management, which was very poor; and

- the quality of resettlement services was very mixed.

The UK’s use of an independent inspectorate for prisons is a very effective check-and-balance for a hard-edged system that can easily corrupt itself behind closed doors. The fact that prisoners feel unsafe in the transportation vans and cell tiers is the biggest red flag for me here.

It’s worth noting, then, that these photos only reflect the visible messy disfunctions of HMP Pentonville. The uptick in violence and drug use was learnt through prisoner questionnaires.

Read the full report here.

Piles of clothing on ridges outside D wing.

2041

HERE PRESS has done it again; it has produced a book that allows us an irresistible glimpse into foreign space and psychology. 2041 is a collection of self-portraits, made by a man, donning makeshift burqas and niqabs, in his home in England.

The title 2041 refers to the name by which the man is known. “2041” made thousands of images with the express intent to share them online with fellow full-coverage enthusiasts.

“Using the camera to articulate a passion he has secretly indulged for decades, the artist appears dozens of times without ever disclosing his image or identity,” says the HERE press release. “Long before 2041 bought his first real burqa online, he began crafting his own versions from draped and folded fabrics in a rich array of textures and colours … ranging from the traditional to the theatrical.”

2041 is part of a connected online community of men and women from across Western Europe and the Gulf States. They are Christians, Muslims and without religion.

This is a gripping book and look into a world that cannot be fully known, nor can be fully verified. What is interesting, therefore, is that without identifiable subjects, the veracity of photography collapses. Or, at the least, we have to completely shift our expectations about what photography provides. The book 2041 is working on, and with, many levels. There’s a motivation by HERE to celebrate photography by revealing its limits and capacity. Despite a reliance on images to connect themselves, 2041 and his cohorts are inhabiting the unphotographable.

As such, 2041 is a playful but earnest exposé of the photographic medium as much as it is this small web of like-minded folks.

A similar type of mood persists in previous titles by HERE. Harry Hardie and Ben Weaver skirt the outer territories of our photo-landscape and delineate the edges. Edmund Clark’s Control Order House took us inside the ordinary domestic spaces of a terror suspect under house arrest. Power was described precisely by what was not photographed. Jason Lazarus’ Nirvana took us into grunge-infused personal histories; the photographs were just a foil to get subjects feting up about beautiful and traumatic pasts.

I, for one, am getting quite excited by HERE’s growing catalogue of ever-so-slightly-disconcerting photobooks.

Between the internet and the veil 2041’s anonymity folds and billows. He remembers the enveloping cassocks and cottas he wore as a choirboy. As an adult, he moved toward total covering. In the early millennium, 2041 his bought his first computer and plugged into an online community that shared his passion.

“What almost all [of the people covering themselves] seem to crave is transcendence of the physical self – or at least being judged on the physical – coupled with the excitement of observing the world unseen, safely cocooned in luxuriant fabrics,” says HERE. “This is the burqa seen in a celebratory light.”

Naturally, I have lots of questions so I dropped Harry at HERE PRESS a line. He put me in touch with Lewis Chaplin who is co-founder of Fourteen Nineteen, but more importantly co-editor of 2041.

Scroll down for our Q&A

Q&A

Prison Photography (PP): Where did you first see and hear about 2041’s photographs?

Lewis Chaplin (LC): I first found these images almost four years ago, while researching emergent subcultures of fetishists/obsessives who were finding community and likemindedness through the internet. Many of these people use Flickr in particular to indulge in their private desires, and it was here that I found 2041’s images. I was struck by the rigidity, flatness and compositional skills that his images had. Compared to most who used the image more as a byproduct or vehicle to access their fetishes, 2041’s images seemed more like the images were performed for the camera and the camera only, for the sake of documentation, rather than for anything else.

PP: Is the book 2041 made in collaboration with the subject? If so, how did you make contact, build trust, ensure discretion?

LC: Yes, it is fully collaborative. Contact was made initially by Harry Hardie , who introduced himself as a publisher, and then I was bought into the conversation. I began a regular correspondence with him, which culminated in a face-to-face meeting and then visits to his house, where we collaborated and photographed each other, and I went through his image archives.

PP: Have all the pictures been verified? Can we know it is the same person under the burqas and niqabs in all the pictures? Does verification matter? Is not knowing something in absolute certainty one of the facets of the images and their use?

LC: I can verify 90% of them through their EXIF data, as we have had access to raw camera files. However, it is not necessarily the same person concealed. I think it is this lack of verification that is the titilating point of these images. Beneath the veil, your physical identity shrinks into a few gestures and outlines, and you can take on the form and countenance of another.

Even now there are images which Ben Weaver (HERE PRESS) and I cannot decide whether they depict our protagonist or others. To be certain though – this form of image-making is a firmly social practice, one based around solid online and offline networks. A few images in the book give this away, and were you to find 2041 online you would find images of me concealed, for example.

PP: Why did you want to make this book?

LC: Because I think that unlike many of the images made by people with strange interests on the internet, these images say something very complex about photography. What I like about these images is that there is that they are purely performative gestures – but yet they give nothing away. They reveal the presence of an individual, but not their likeness, or an accurate representation. Something about the concealment of desire, or the hiding of the true likeness of an object in these images actually feels like a very nuanced statement on photography, that at no stage in the process ever actually tries to use the camera to bear any details, or describe anything accurately.

PP: How many potential subjects and/or images did you have to choose from in making the book? What makes 2041’s images special — some aspects of aesthetics, or merely their availability?

LC: It wasn’t so much a matter of choice, more that these images asked for some kind of sequencing and exploring. There is definitely an aesthetic dimension of these images that is appealing – the composition and contrast between flatness and texture, the shapes are unlike others I have seen – and there is also a lot of time and effort that has gone into these. 2041 is also an actor, and a painter. You can see the influence of classical painting on some of his poses and crops. He is also akin to humour and self-deprecation, you can see it sometimes.

PP: 2041 wishes to remain anonymous. Obviously, as the editor, you’re a legitimate proxy to whom I can talk. I want to ask what 2041 thinks of the book?

LC: Let’s ask him once he has seen it!

PP: What do members of the online burqa fetish community think? What do you think they might think?

LC: I don’t think it has made its way through to these channels, but I would hope that what they see here is that we are not trying to ridicule or pass judgement through our scrutiny. This book I hope comes off as a sincere tribute to photography being used in a genuinely interesting way that talks about self-perception, the way images are used on the internet and so many other things, through the prism of a very personal, domestic and specific application of the camera.

PP: Do we understand what the burqa is and what it does?

LC: In these images the burqa, niqab or any other Muslim garment is a means to an end in some way. You can see in some of 2041’s experimentations that it is just about complete coverage through any means. He is not wearing a burqa in most images, in fact. The removal of physical presence is the goal here – it is never about using the burqa in a subversive or political way.

PP: Thanks, Lewis.

LC: Thank you, Pete.

2041, the book

170 x 240mm, 120pp + 6pp insert

72 photographs + 1 illustration

Offset lithoprint on coated & uncoated paper Sewn in sections with loose dust jacket

Foil title

Choice of 3 cover ‘photo insert’ cards

Text, illustration & photographs by 2041

Edited & designed by Lewis Chaplin & Ben Weaver Edition of 500.

Photo: Spike Aston

Photography is often best kept simple. Likewise, the description of photography is, also, best kept simple. So let’s do that.

Disposable is a photography project that puts cameras in the hands of a dozen or so homeless men and women in London, England. Very straightforward. Disposable garners images that have given – in their production – moments to create and reflect, and – in their viewing – moments for reflection upon creative practices toward a more equal society. Right? What use is this post, and what use the participants’ efforts, and what use the program coordination efforts of Adele Watts if we’re not to reflect on the issues of poverty and homelessness in our society?

Disposable began in 2012. Disposable is grassroots. The men and women involved consider themselves a collective.

Watts worked closely with homeless artists over the period of a year and developed a body of original photographs.

“Without a brief, each participant took single-use cameras away, returning them a couple of weeks later to be developed and to look though the work and discuss it together,” explains Watts.

“Photography is a science of seeing. I like to see ordinary things too because they can tell you a lot about where you are if you don’t know. You can discover many beautiful and interesting worlds that don’t seem like worlds without photography,” says participant Spike Aston.

In the past 18 months, Disposable has mounted three exhibitions — at a Central London outreach venue in April 2013, and later at Four Corners Gallery, Bethnal Green in October 2013 and Ziferblat, Shoreditch in August 2014.

“Disposable allows us to view homelessness from the rich and insightful perspective of those experiencing it, but does so with refreshing subtlety. This is achieved through a belief in cultivating authorial voice and expression without exception, which is truly at the heart of the project and all those who have brought it to life,” says Claire Hewitt who provides texts for the Disposable newsprint publication. “I was overwhelmed by the ways in which they had each nurtured their own visual languages.”

A collection of photographic works by Bill Wood, R.O.L and Spike Aston, Disposable’s most devoted members — has now been brought together in a 16-page newspaper publication.

The Disposable newsprint publication is available as an insert to the latest issue of Uncertain States a lens-based broadsheet. It is distributed through and available at: Brighton Photo Biennial 2014, V&A London, Tate Britain, Four Corners Gallery, Ikon Gallery & Library of Birmingham, Flowers East, Turner Contemporary, Margate.

Keep in touch with the project via Adele Watts’ website and Twitter, and the Disposable Tumblr.

Photo: Bill Wood

Photo: Bill Wood

Photo: R.O.L.

Photo: R.O.L.

Photo: R.O.L.

Photo: Spike Aston

Photo: Spike Aston

Photo: Spike Aston

Disposable Insert. Uncertain States. Open Call. Issue 20

Disposable

Edition of 5000 copies

290mm x 370mm

16 pages printed full colour on 52gsm recycled newsprint. Inserted into Uncertain States Issue 20, a lens-based broadsheet.

Photographic works by Bill Wood, R.O.L & Spike Aston.

Texts by Clare Hewitt & Jenna Roberts.

Edited by Adele Watts.

UPDATED: SEPT 4TH 2012. 9AM BST

A week after this blog post went to press, the Prison Reform Trust reported that 77 of the 131 prisons in England and Wales held more inmates than stated capacity.

London’s HMP Wandsworth, which is one of the the three prisons in Elphick’s photographs, is the seventh most overcrowded prison in the UK with 1,191 men being held in a facility only designed for 730 men. Wandsworth operates at 163% capacity.

In total, UK prisons hold 7,300 persons more than they were designed for.

– – – – – –

Hugh Elphick is a young British photographer who, in early 2011, took a cool and curious look at London prisons for his undergraduate photography BFA. The series is Inside.

“I wanted to produce images which intrigued more than shocked,” says Elphick. “I discovered how much prisons actually blend into their surroundings and used this blurring the boundaries, with some of the angles I shot.”

In the series of six photos, Elphick shows us the red-brick exteriors of three prisons – Pentonville, Wandsworth and Wormwood Scrubs. Elphick was working close to Wormwood Scrubs and began to wonder about human rights, the acceptability of the prison system, and if prisons work.

“In England, it is not a commonly known fact [that the UK has the second highest rate of incarceration after the U.S. among industrialised nations] and that it is not something that most people worry about,” says Elphick. “It could be argued that there is more concern that prison sentences are not long enough or that there are moral disparities in sentencing. However, this is not to say that there are not a large proportion of people who see the wider picture.”

Elphick’s focus specifically is about the age of these *famous* Victorian prisons. The Victorian era is steeped in imagery of inequality, squalor and hardship for the working classes. For Elphick, there are points of comparison between the class-stratified 19th century and the inequalities of the modern era and especially today in a time of austerity and cuts in services.

“Victorian architecture offers an allegoric association with harsh systems and possibly with periods such as the late 70 early 80’s economic downturn. Such institutional auras, I believe, explore some of the dilemmas and imbalances of our society,” says Elphick. “These prisons show how little progression there has been in the prison system due to confused government policies.”

Much like the approach of German photographer Christiane Feser, Elphick’s interest is in how these large, alien institutions interact visually with nearby residential communities. Unlike in the U.S., the economic fortunes of the nearby communities in the UK are not tied directly to or dependent upon the operation of a prison. These UK prisons are part of the urban puzzle but quite opposite to the prison-towns of central Wyoming or eastern Washington, which come to rely on jobs as traditional agriculture and industry wane. There is not the same attrition and competition in the job market in central London. Prisons in the UK are not perceived of as big business, partly because by comparison to the bloated U.S. prison system, it isn’t.

In fact, Elphick argues that prisons have almost become mundane in UK cities. He writes in his artist statement:

“The fragmentary nature of London’s development, and its destruction in WW2, have meant a breadth of architectural forms have spread into areas surrounding the prisons. The prisons no longer stand as the monolithic symbols of suffering they once did, and have melted into the architecture of our city. They are taken for granted, dismissed”

This is a peculiar paradox to deal with in images; subjects hidden in plain sight.

“I set out to make a graphic and symmetrical set of images and fortunately there were features which allowed me to do this and at the same time inject some curiosity such as the splash of paint, bench or repaired hole,” says Elphick. “The walls are rigid and literal boundaries which can be translated metaphorically and ironically in many ways to question the justice system and inequalities in society.”

– – – –

Inside was exhibited in the three-person show Behind Bars at One & A Half Gallery, London in September, 2011.

Bettina von Kameke‘s series Wormwood Scrubs is a reflective look at the communal life of prisoners inside one of Britain’s most notorious prisons.

Wormwood Scrubs (Her Majesty’s Prison) is well known in Britain through both popular culture and sporadic news stories about the latest infamous prisoner. It is a institution everyone has heard, some would claim to know about, but in fact only a few truly know. Those few would be the staff and prisoners.

Von Kameke says:

“I was surprised at how respectful the interaction between staff and prisoners was. Of course I was aware that there is drug-dealing inside and it is a hard prison. I could feel the intensity and harshness of the energy… I reflected it in the sadness, heaviness, anger and frustration through the expressions on their faces. But the objective is to show the humanity in the system.”

I am impressed by von Kameke’s awareness (and depiction) of communal living.

“I question and explore the interior and exterior conditions, means and forces, which make a communal life sustainable. My photographs disclose the aesthetics of an enclosed community, which I carefully observe through the viewfinder of the camera.” (Source)

Prison jobs and recreational time are what make incarceration sustainable, and by that I mean as free from waste and repetition as possible.

Prisoners never make direct eye contact with von Kameke’s lens; she shoots as if she is not there. This, I suspect, has a lot to do with the amount of time she spent in Wormwood Scrubs; she spent over six months on the prison wings.*

She and the prisoners probably did have relationships, but they are not the subject of von Kameke’s photography; attentions are elsewhere … apparently.

Between von Kameke and her subjects is acceptance and restraint, almost to the point of collaboration. It cannot be overstated how difficult this is to achieve in a prison environment when everyone potentially has something to pursue and gain through interactions.

One final thing to note is the overlap in atmosphere between Wormwood Scrubs and von Kameke’s earlier series Tyburn Tree, which depicts the Benedictine Nuns of the Tyburn Tree Convent, London. Communal living within total institutions can be both enforced and voluntary.

Wormwood Scrubs is on show at Great Western Studios, 65 Alfred Road, London W2 5EU until March 11th.

More images at the Guardian.

* I always contend that the best prison photography projects result from a long term engagement with the subject. Von Kameke’s Wormwood Scrubs bears out this thesis oncemore.

Photography and fingerprinting room.

David Moore has an uncanny knack of gaining access to sites most photographers might think are beyond reach.

In the Summer of 2009, Moore took advantage of a short-window of time during which the cells inside Paddington Green Police Station sat empty. The survey Moore completed – a series entitled 28 Days – was the first foray into this infamous jail. Prison Photography is proud to publish these images for the very first time.

[Keep reading below]

Chair.

Forensic pod.

Paddington Green Police Station is structurally banal. Constructed in the late sixties, its functionalism is belied somewhat by a concrete-lovers facade. For Britons, Paddington Green means one thing: Terrorism. Built into and underneath the station are sixteen cells and a purpose built custody suite; extraordinary hardware for a police station, but not for the interrogation of high-level terror suspects.

In the 1970’s many IRA suspects were incarcerated at Paddington Green prior to appearing in court. At that time, the period of initial detention was up to 48 hours, this could be extended by a maximum of five additional days by the Home Secretary. (Prevention of Terrorism Act, Northern Ireland, 1974). British terror legislation was not renewed until the Millennium.

The Terrorism Act of 2006 increased the limit of pre-charge detention for terrorist suspects to 28-days, hence Moore’s title for the work.

Originally, the Labour Government and Prime Minister Tony Blair, had pushed for a 90-day detention period, but following a rebellion by Labour MPs, it was reduced to 28-days after a vote in the House of Commons.

[Keep reading below]

Control room.

Chair, police interview room.

Holding cell.

In 2005, Lord Carlile (a hero of photographers, as a key person in reversing abused UK police stop-and-search procedures) was appointed independent reviewer for the government’s anti-terrorism legislation. His team visited Paddington Green in May, 2007 and issued a damning report on its inadequacy as a modern facility for the detention of humans for such extended periods.

The facilities […] were designed when the station was built in the late 1960s in order to deal with terrorism suspects from Northern Ireland – a far different threat from that faced from international terrorism today, in terms of scale and complexity. The main deficiencies of Paddington Green are as follows:

* there are only 16 cells. Over 20 people at a time were arrested during individual terrorism investigations in both 2005 and 2006 and some had to be sent to Belgravia police station, which is not set up to deal with terrorism suspects. In addition, the normal day-to-day work of Paddington Green police station, which serves the local neighbourhood, was severely disrupted.

* there are no dedicated facilities for forensic examination of suspects on arrival. Cells have to be to specially prepared for this purpose, which is time consuming and further exacerbates the lack of accommodation.

* there is no dedicated space for exercise. Part of the car park can be cleared to provide a small exercise yard but this takes time to arrange and the car park is overlooked. This is likely to reduce considerably opportunities for exercise.[48]

* only one room is provided for suspects to discuss their cases in confidence with a solicitor.

* there are no facilities on site for the forensic examination of equipment such as computer hard drives.

* the videoconferencing room is too small to accommodate judicial hearings on the extension of the period of detention. Such hearings are usually now held in the entrance lobby, which is itself cramped, is a thoroughfare into the custody suite, and opens into the staff toilets at the back. It is clearly an inappropriate location for such a crucial part of the detention process.

(Source)

And so it was, shortly after the completed £490,000 refurbishment of Paddington Green Police Station, Moore photographed to the smell of fresh paint.

[Keep reading below]

CCTV camera with courtesy screening over toilet, holding cell D

Holding cell D.

28 Days is a continuation of Moore’s preoccupation with sites of state apparatus, but this was not always his interest. During the nineties, Moore worked in New York as a commercial photographer, Upon his return to his Britain, he spent three years piecing together The Velvet Arena (1994), a look at the textures, couture and gestures of high society, openings and schmoozing … canapes and all.

From here Moore, still concerned with the dark weight of the familiar made photographs of the House of Commons. He describes The Commons (2004) as a forensic view. “British people know what the House of Commons looks like,” said Moore via Skype interview. His response was to get close and change the view; he focused on corners, carpets, perched flies, scratches in the wood and banisters.

The Commons was pivotal in Moore’s development. He argues that photography has always been entangled in politics, specifically the British Empire. Following the destruction by fire of the existing Houses of Parliament on 16 October 1834, Barry and Pugin designed the new houses for British law with Gothic-Revivalist importance. They were completed in 1847. Photography’s earliest manifestation came about in 1839 with the daguerreotype.

Law, reason, progress, conquest, taxonomy and technology drove the British Empire through the end of the 19th century. Photography, with its will to objectivity, played its part in stifling cultural relativism; it disciplined both colonialist and colonised. Against this history, The Commons, for Moore, was “born of political frustration.”

“It was important for me to break it down. I am probably most influenced by Malcolm McLaren than anyone else,” says Moore.

[Keep reading below]

Solicitors’ consultation room

Virtual courtroom.

“My volition as a photographer goes back to the want to use it as a democratic tool. Looking at state apparatus and panoptic sites, I see my work as an act of visual democracy. Any small chip I can make.”

In 2008, Moore made quite a large chip. For The Last Things, he negotiated access to the Ministry of Defence’s crisis command centre deep beneath the streets of Whitehall, London. Moore got the pictures no other photographer ever had, or ever will. Read my article for Wired.com about Moore’s experience working in the subterranean complex that – to this day – officially “does not exist.”

The Last Things more than any other portfolio, opened the door for Moore to work at Paddington Green. It was a body of work with which he could show he could be trusted. Besides the Police Station was vacant. “It was relatively low security,” explains Moore.

“Paddington Green was very different to the MoD crisis command center. Paddington Green is imbued with a history and a trajectory of history. I know about [IRA] terrorism and about interview techniques and who’d been held in there over the years.”

For Moore, 28 Days is a contrast of the old and the new. An old building with new fixtures. Old procedures replaced by new codes of conduct. “There were definitely some opinions from older police officers: ‘These are terrorists, what does it matter if a cell is painted or not?’ and there was a mix of young and old police officers. The architecture reflected the changing Metropolitan police,” says Moore.

Moore’s work at Paddington Green is a glimpse of an institution in transition; in a moment and not in use. It could be said the stakes were low for London’s Metropolitan Police; that the risk was minimal. It is likely Paddington Green Police Station will cease to operate as the first stop for terrorist suspects. Plans are afoot for a new purpose-built facility. For the authorities, Moore’s work is transparency, for us it is curiosity sated, and for the photographer it is a small victory for “visual democracy”.

Exercise area.

All Images Courtesy of David Moore

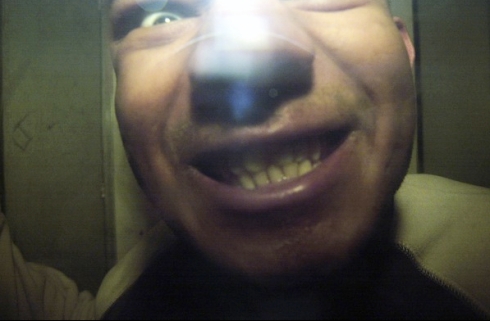

I grinned ear to ear yesterday when Foto8 In & Out the Old Bailey ran Ben Graville‘s work of remand prisoners (and security guards) in reaction to the press camera up against reinforced glass. It is a novel, clear and entertaining project. Why did it take someone so long to put a series like this together?

If photography is – in cases – intended to plumb the human soul and aggressively seek out human frailty, pride, conversion, obstinacy, etc., then the back of a cop-van is probably a good place to start. Folk on their way to trial are going to have a lot to say about a) their charge b) their case c) everything else that the first two don’t cover.

James Luckett over at consumptive coined the term “Photo booth from Hell” and he’s right on the money. They sit in a big white box subject to a camera behind a small glass rectangle. The environment is claustrophobic, impersonal and germy.

If a prisoner has the forethought or experience they may ready him or herself for the photograph. If not they’ll be captured on film anyway.

How balanced is the interaction between camera and subject? The image will serve the media more than it will serve the balance or accuracy of the court case. But this is a truism.

Graville is interested in state enforced anonymity and the effect it has on mystifying and intensifying understanding;

It should be no shock that many prisoners perform, gurn and address Graville’s camera directly; they are – literally and legally – in a transitory, undecided state. If I was in this same situation, I think it would be a natural reflex-come-obligation to self-represent to the camera. These prisoners may not have chosen to have the camera in their space, but they have the choice of how to address it.

… and of course there’s always a security guard who gets in on the action.