You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘IRA’ tag.

Photography and fingerprinting room.

David Moore has an uncanny knack of gaining access to sites most photographers might think are beyond reach.

In the Summer of 2009, Moore took advantage of a short-window of time during which the cells inside Paddington Green Police Station sat empty. The survey Moore completed – a series entitled 28 Days – was the first foray into this infamous jail. Prison Photography is proud to publish these images for the very first time.

[Keep reading below]

Chair.

Forensic pod.

Paddington Green Police Station is structurally banal. Constructed in the late sixties, its functionalism is belied somewhat by a concrete-lovers facade. For Britons, Paddington Green means one thing: Terrorism. Built into and underneath the station are sixteen cells and a purpose built custody suite; extraordinary hardware for a police station, but not for the interrogation of high-level terror suspects.

In the 1970’s many IRA suspects were incarcerated at Paddington Green prior to appearing in court. At that time, the period of initial detention was up to 48 hours, this could be extended by a maximum of five additional days by the Home Secretary. (Prevention of Terrorism Act, Northern Ireland, 1974). British terror legislation was not renewed until the Millennium.

The Terrorism Act of 2006 increased the limit of pre-charge detention for terrorist suspects to 28-days, hence Moore’s title for the work.

Originally, the Labour Government and Prime Minister Tony Blair, had pushed for a 90-day detention period, but following a rebellion by Labour MPs, it was reduced to 28-days after a vote in the House of Commons.

[Keep reading below]

Control room.

Chair, police interview room.

Holding cell.

In 2005, Lord Carlile (a hero of photographers, as a key person in reversing abused UK police stop-and-search procedures) was appointed independent reviewer for the government’s anti-terrorism legislation. His team visited Paddington Green in May, 2007 and issued a damning report on its inadequacy as a modern facility for the detention of humans for such extended periods.

The facilities […] were designed when the station was built in the late 1960s in order to deal with terrorism suspects from Northern Ireland – a far different threat from that faced from international terrorism today, in terms of scale and complexity. The main deficiencies of Paddington Green are as follows:

* there are only 16 cells. Over 20 people at a time were arrested during individual terrorism investigations in both 2005 and 2006 and some had to be sent to Belgravia police station, which is not set up to deal with terrorism suspects. In addition, the normal day-to-day work of Paddington Green police station, which serves the local neighbourhood, was severely disrupted.

* there are no dedicated facilities for forensic examination of suspects on arrival. Cells have to be to specially prepared for this purpose, which is time consuming and further exacerbates the lack of accommodation.

* there is no dedicated space for exercise. Part of the car park can be cleared to provide a small exercise yard but this takes time to arrange and the car park is overlooked. This is likely to reduce considerably opportunities for exercise.[48]

* only one room is provided for suspects to discuss their cases in confidence with a solicitor.

* there are no facilities on site for the forensic examination of equipment such as computer hard drives.

* the videoconferencing room is too small to accommodate judicial hearings on the extension of the period of detention. Such hearings are usually now held in the entrance lobby, which is itself cramped, is a thoroughfare into the custody suite, and opens into the staff toilets at the back. It is clearly an inappropriate location for such a crucial part of the detention process.

(Source)

And so it was, shortly after the completed £490,000 refurbishment of Paddington Green Police Station, Moore photographed to the smell of fresh paint.

[Keep reading below]

CCTV camera with courtesy screening over toilet, holding cell D

Holding cell D.

28 Days is a continuation of Moore’s preoccupation with sites of state apparatus, but this was not always his interest. During the nineties, Moore worked in New York as a commercial photographer, Upon his return to his Britain, he spent three years piecing together The Velvet Arena (1994), a look at the textures, couture and gestures of high society, openings and schmoozing … canapes and all.

From here Moore, still concerned with the dark weight of the familiar made photographs of the House of Commons. He describes The Commons (2004) as a forensic view. “British people know what the House of Commons looks like,” said Moore via Skype interview. His response was to get close and change the view; he focused on corners, carpets, perched flies, scratches in the wood and banisters.

The Commons was pivotal in Moore’s development. He argues that photography has always been entangled in politics, specifically the British Empire. Following the destruction by fire of the existing Houses of Parliament on 16 October 1834, Barry and Pugin designed the new houses for British law with Gothic-Revivalist importance. They were completed in 1847. Photography’s earliest manifestation came about in 1839 with the daguerreotype.

Law, reason, progress, conquest, taxonomy and technology drove the British Empire through the end of the 19th century. Photography, with its will to objectivity, played its part in stifling cultural relativism; it disciplined both colonialist and colonised. Against this history, The Commons, for Moore, was “born of political frustration.”

“It was important for me to break it down. I am probably most influenced by Malcolm McLaren than anyone else,” says Moore.

[Keep reading below]

Solicitors’ consultation room

Virtual courtroom.

“My volition as a photographer goes back to the want to use it as a democratic tool. Looking at state apparatus and panoptic sites, I see my work as an act of visual democracy. Any small chip I can make.”

In 2008, Moore made quite a large chip. For The Last Things, he negotiated access to the Ministry of Defence’s crisis command centre deep beneath the streets of Whitehall, London. Moore got the pictures no other photographer ever had, or ever will. Read my article for Wired.com about Moore’s experience working in the subterranean complex that – to this day – officially “does not exist.”

The Last Things more than any other portfolio, opened the door for Moore to work at Paddington Green. It was a body of work with which he could show he could be trusted. Besides the Police Station was vacant. “It was relatively low security,” explains Moore.

“Paddington Green was very different to the MoD crisis command center. Paddington Green is imbued with a history and a trajectory of history. I know about [IRA] terrorism and about interview techniques and who’d been held in there over the years.”

For Moore, 28 Days is a contrast of the old and the new. An old building with new fixtures. Old procedures replaced by new codes of conduct. “There were definitely some opinions from older police officers: ‘These are terrorists, what does it matter if a cell is painted or not?’ and there was a mix of young and old police officers. The architecture reflected the changing Metropolitan police,” says Moore.

Moore’s work at Paddington Green is a glimpse of an institution in transition; in a moment and not in use. It could be said the stakes were low for London’s Metropolitan Police; that the risk was minimal. It is likely Paddington Green Police Station will cease to operate as the first stop for terrorist suspects. Plans are afoot for a new purpose-built facility. For the authorities, Moore’s work is transparency, for us it is curiosity sated, and for the photographer it is a small victory for “visual democracy”.

Exercise area.

All Images Courtesy of David Moore

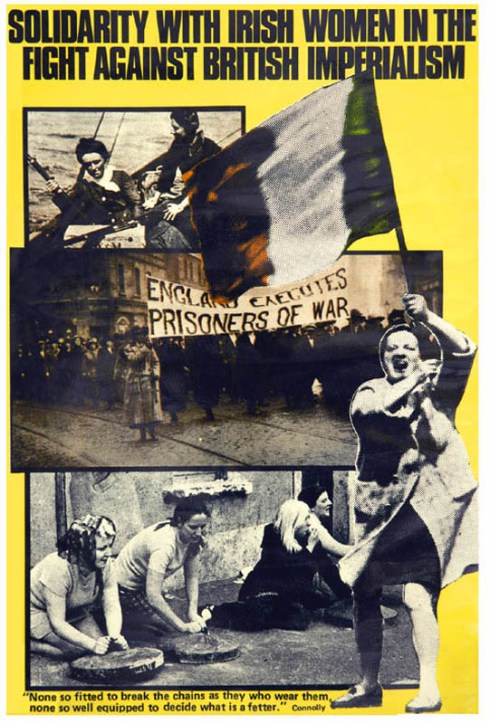

During 1981, there were two hunger strikes – the culmination of a five-year protest during The Troubles by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland.

Ten men died.

28 years ago today, 3rd October, the strikes were called to an official end.

The inspiring Just Seeds Collective which peddles art to fund prison rights activism pointed me via its blog toward the Poster Film-Collective of London.

The Poster Film-Collective is a unique archive of graphics for African, Cultural, International, Irish, British and Women’s causes. With direct politics and robust graphics, poster arts are a nostalgic favourite for many art historians.

‘The Troubles’ of Northern Ireland are a very difficult topic for me to discuss; but not because I am close or emotionally compromised and not because I know or knew anyone involved. I grew up just the other side of the Irish Sea, but Belfast may as well have been the other side of the world to me. I was raised Catholic and my Mum’s family are from the Republic of Ireland. Yet, as a child my family rarely discussed the situation in Northern Ireland. Even in 1996, when the IRA bombed the Arndale shopping centre in Manchester (just down the M61 from my home town) the conflict was still too abstract and ancient for my teenage mind to comprehend.

I think any political labels or alliances that would fall upon my family were deflected by a distant dismay at the violence of the time. ‘The Troubles’ of Northern Ireland are not something I feel comfortable idealising; rather limply I retreat to the cliche that one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter. All sides (there were more than two) were guilty of arrogance, obstinacy and extreme violence. The ideological brutality played out on the streets was matched by that meted out in the prisons, most notably Long Kesh, later renamed The Maze.

It is a lingering guilt for me that ‘The Troubles’ have always been historical … historicised. It is this guilt that accounts for the fact I’ve not before discussed Donovan Wylie’s The Maze on Prison Photography. Wylie is saturated in Irish history – it is his life’s vocation. On the other hand, I would be a fraud if I attempted to summarise the complex events of a physically-close-culturally-distant conflict.

It is with similar guilt I refer readers – in the first instance – not to news reports or academic reflection but to a 2008 film. But, I do so because Steve McQueen’s Hunger is a breath-taking portrayal of a life-taking episode in the history of Maze prison. It is a wonderful observation of British prisons, Irish Republican solidarity and inmate management in the face of political protest.

McQueen, in his directorial debut, specialises in long uninterrupted shots which grip time (and all its anguish) and forces the politicised narratives through the mangle. He flattens and simplifies the visuals drawing out the incredible fragility of human skin, snow-flake, fly, lamb, ribcage … McQueen is surely a great photographer too.

Through Donovan Wylie’s work I learnt of Dr. Louise Purbrick’s excellent continuing research “concerned above all with the meanings of things and how those meanings are contained or revealed, experienced and theorised.” Purbrick wrote the essay for Donvan Wylie’s book, Maze. That was in 2004. In 2007, Purbrick extended the survey, jointly editing the book Contested Spaces. It analysed the “divided cities of Berlin, Nicosia and Jerusalem, the borderlands between the United States and Mexico, battlefields in Scotland and South Africa, a Nazi labour camp in Northern France, memorial sites in Australia and Rwanda, and Abu Ghraib.”

Purbrick worked with another academic Cahal McLaughlin on the oral history & documentary film project Inside Stories featuring Irish Republican Gerry Kelly, Loyalist Billy Hutchinson and ex-warder Desi Waterworth. And it is here I start (and I encourage you to start), with personal testimony when trying to understand ‘The Troubles’.

Donovan Wylie has continued his visual archaelogy of Irish history with Scrapbook.

Born in Belfast in 1971, DONOVAN WYLIE discovered photography at an early age. He left school at sixteen, and embarked on a three-month journey around Ireland that resulted in the production of his first book, 32 Counties (Secker and Warburg 1989), published while he was still a teenager. In 1992 Wylie was invited to become a nominee of Magnum Photos and in 1998 he became a full member. Much of his work, often described as ‘Archaeo-logies’, has stemmed primarily to date from the political and social landscape of Northern Ireland.

Born in Belfast in 1971, DONOVAN WYLIE discovered photography at an early age. He left school at sixteen, and embarked on a three-month journey around Ireland that resulted in the production of his first book, 32 Counties (Secker and Warburg 1989), published while he was still a teenager. In 1992 Wylie was invited to become a nominee of Magnum Photos and in 1998 he became a full member. Much of his work, often described as ‘Archaeo-logies’, has stemmed primarily to date from the political and social landscape of Northern Ireland.

LOUISE PURBRICK is Senior Lecturer in the History of Art and Design at the University of Brighton, UK. She is author of The Architecture of Containment in D. Wylie, The Maze (Granta, 2004) and, with John Schofield and Axel Klausmeier, editor of Re-Mapping the Field: New Approaches to Conflict Archaeology (Westkreuz-Verlag, 2006). She also works on the material culture of everyday life and has written The Wedding Present: Domestic Life beyond Consumption (Ashgate, 2007) (Source)

CAHAL McLAUGHLIN is Senior Lecturer in the School of Film, Media and Journalism at the University of Ulster. He is also a documentary filmmaker and is currently working on a Heritage Lottery Funded project, ‘Prison Memory Archive’.