You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Northern Ireland’ tag.

A bathroom inside the Maze Prison, near Lisburn, Northern Ireland, on Tuesday, April. 11, 2006.

Andrew McConnell‘s work The Last Colony from the Western Sahara has gained some traction recently, promoted at DVAFOTO and backed up by TPP.

McConnell is from Northern Ireland so I was not too surprised upon looking through his portfolio to find a series on the Maze prison.

I’ve seen a few projects from Maze Prison – the most well-known being that of Donovan Wylie – and yet a few of McConnell’s images really stood out.

STATEMENT

McConnell: “HM Maze Prison, also known as Long Kesh and the H-Blocks, held some of the most dangerous men in Europe during its 30 year operation. The prison closed in September 2000 after 428 prisoners had been released under the Good Friday Agreement. There are now plans to turn the abandoned site into a national football stadium.”

The bathroom image (above) is admittedly more powerful to me, having seen the bloodied-knuckle washing scenes in Steve McQueen’s powerful debut film Hunger.

Also, admittedly the image of the football (below) is more loaded given the now-defunct plans to convert the site into a national stadium.

In January 2009 plans to build the £300 million multi-purpose stadium were officially axed with politicians saying plans to start the construction of the stadium wouldn’t be reconsidered for another 3 to 4 years. (Source)

An old football lies in the exercise yard of the Maze Prison, July 18, 2006.

I had been under the impression every structure at the Maze had been demolished but apparently not:

Discussion is still ongoing as to the listed status of sections of the old prison. The hospital and part of the H-Blocks are currently listed buildings, and would remain as part of the proposed site redevelopment as a “conflict transformation centre” with support from republicans such as Martin McGuinness and opposition from unionists like Nigel Dodds who are against erecting a memorial to those who died during the hunger strike. (Source)

Which ties nicely back into the crucial question about McConnell’s photographs of the site. Are these photographs of memory, for memory, for memorial? What audience do they serve?

It seems to me that politics and emotions vary so wildly, that when a photographer (so soon after decommission) takes on a contested site such as this, his/her photographs are open to many different interpretations. The Maze and its history are fascinating, discussion-worthy topics, but is it the case here that the images are nothing more than notable ‘urban exploration‘?

Donovan Wylie dodged this suspicion by documenting over a five-year period the slow demolition of The Maze. Wylie has talked about wanting to create an archive of this transitional moment. However, if a photographer’s series is too brief (either within its own boundaries or by comparison to another practitioner’s series) then how is it justified or explained?

I don’t want to be dismissive here, as I think this is a problem many political-documentary photographers face – namely, their work may not adequately reflect or contain the disputed political landscape it references.

Perhaps we should read McConnell’s The Maze as undefinable and undecided, just as the former prison site remains?

The Cages of the Maze Prison, Northern Ireland, July 18, 2006.

Biography

Andrew McConnell was born in Northern Ireland in 1977 and began his career as a press photographer covering the closing stages of the conflict in his homeland and the transition to peace. He later worked in Asia and moved to Africa in 2007 to document the issues and stories of that continent which are widely overlooked by the international media.

His images have appeared appeared internationally in publications such as National Geographic Magazine, Newsweek, Time magazine, The New York Times, The Guardian, FT Magazine, L’Express, Vanity Fair (Italy), the Sunday Times Magazine, and Internazionale.

During 1981, there were two hunger strikes – the culmination of a five-year protest during The Troubles by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland.

Ten men died.

28 years ago today, 3rd October, the strikes were called to an official end.

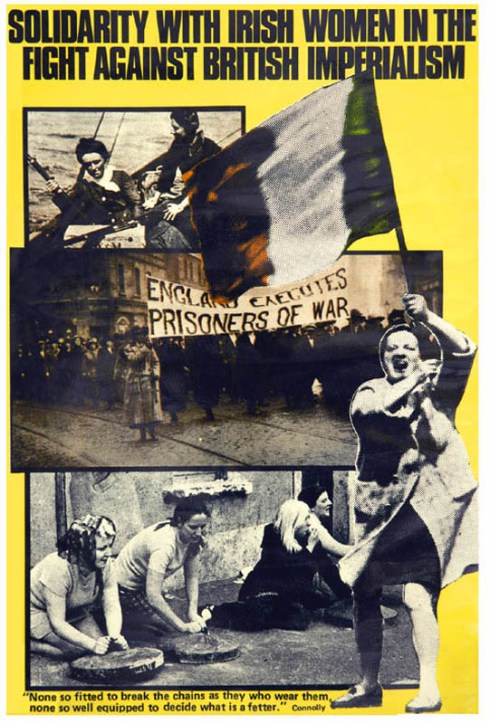

The inspiring Just Seeds Collective which peddles art to fund prison rights activism pointed me via its blog toward the Poster Film-Collective of London.

The Poster Film-Collective is a unique archive of graphics for African, Cultural, International, Irish, British and Women’s causes. With direct politics and robust graphics, poster arts are a nostalgic favourite for many art historians.

‘The Troubles’ of Northern Ireland are a very difficult topic for me to discuss; but not because I am close or emotionally compromised and not because I know or knew anyone involved. I grew up just the other side of the Irish Sea, but Belfast may as well have been the other side of the world to me. I was raised Catholic and my Mum’s family are from the Republic of Ireland. Yet, as a child my family rarely discussed the situation in Northern Ireland. Even in 1996, when the IRA bombed the Arndale shopping centre in Manchester (just down the M61 from my home town) the conflict was still too abstract and ancient for my teenage mind to comprehend.

I think any political labels or alliances that would fall upon my family were deflected by a distant dismay at the violence of the time. ‘The Troubles’ of Northern Ireland are not something I feel comfortable idealising; rather limply I retreat to the cliche that one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter. All sides (there were more than two) were guilty of arrogance, obstinacy and extreme violence. The ideological brutality played out on the streets was matched by that meted out in the prisons, most notably Long Kesh, later renamed The Maze.

It is a lingering guilt for me that ‘The Troubles’ have always been historical … historicised. It is this guilt that accounts for the fact I’ve not before discussed Donovan Wylie’s The Maze on Prison Photography. Wylie is saturated in Irish history – it is his life’s vocation. On the other hand, I would be a fraud if I attempted to summarise the complex events of a physically-close-culturally-distant conflict.

It is with similar guilt I refer readers – in the first instance – not to news reports or academic reflection but to a 2008 film. But, I do so because Steve McQueen’s Hunger is a breath-taking portrayal of a life-taking episode in the history of Maze prison. It is a wonderful observation of British prisons, Irish Republican solidarity and inmate management in the face of political protest.

McQueen, in his directorial debut, specialises in long uninterrupted shots which grip time (and all its anguish) and forces the politicised narratives through the mangle. He flattens and simplifies the visuals drawing out the incredible fragility of human skin, snow-flake, fly, lamb, ribcage … McQueen is surely a great photographer too.

Through Donovan Wylie’s work I learnt of Dr. Louise Purbrick’s excellent continuing research “concerned above all with the meanings of things and how those meanings are contained or revealed, experienced and theorised.” Purbrick wrote the essay for Donvan Wylie’s book, Maze. That was in 2004. In 2007, Purbrick extended the survey, jointly editing the book Contested Spaces. It analysed the “divided cities of Berlin, Nicosia and Jerusalem, the borderlands between the United States and Mexico, battlefields in Scotland and South Africa, a Nazi labour camp in Northern France, memorial sites in Australia and Rwanda, and Abu Ghraib.”

Purbrick worked with another academic Cahal McLaughlin on the oral history & documentary film project Inside Stories featuring Irish Republican Gerry Kelly, Loyalist Billy Hutchinson and ex-warder Desi Waterworth. And it is here I start (and I encourage you to start), with personal testimony when trying to understand ‘The Troubles’.

Donovan Wylie has continued his visual archaelogy of Irish history with Scrapbook.

Born in Belfast in 1971, DONOVAN WYLIE discovered photography at an early age. He left school at sixteen, and embarked on a three-month journey around Ireland that resulted in the production of his first book, 32 Counties (Secker and Warburg 1989), published while he was still a teenager. In 1992 Wylie was invited to become a nominee of Magnum Photos and in 1998 he became a full member. Much of his work, often described as ‘Archaeo-logies’, has stemmed primarily to date from the political and social landscape of Northern Ireland.

Born in Belfast in 1971, DONOVAN WYLIE discovered photography at an early age. He left school at sixteen, and embarked on a three-month journey around Ireland that resulted in the production of his first book, 32 Counties (Secker and Warburg 1989), published while he was still a teenager. In 1992 Wylie was invited to become a nominee of Magnum Photos and in 1998 he became a full member. Much of his work, often described as ‘Archaeo-logies’, has stemmed primarily to date from the political and social landscape of Northern Ireland.

LOUISE PURBRICK is Senior Lecturer in the History of Art and Design at the University of Brighton, UK. She is author of The Architecture of Containment in D. Wylie, The Maze (Granta, 2004) and, with John Schofield and Axel Klausmeier, editor of Re-Mapping the Field: New Approaches to Conflict Archaeology (Westkreuz-Verlag, 2006). She also works on the material culture of everyday life and has written The Wedding Present: Domestic Life beyond Consumption (Ashgate, 2007) (Source)

CAHAL McLAUGHLIN is Senior Lecturer in the School of Film, Media and Journalism at the University of Ulster. He is also a documentary filmmaker and is currently working on a Heritage Lottery Funded project, ‘Prison Memory Archive’.