You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Convergence’ category.

It’s unmistakable. That gazebo. That hexagonal cover to that picnic table. One needn’t notice the flowers, or even the poster, to the memory of Tamir Rice to recognize this utility structure as that under which the 12-year-old was murdered by Cleveland police. Even the bollards between us the viewer and the polygon shelter seem instantly familiar. For it was between those bollards and the gazebo that the cop car screeched to a halt, it’s door flew open and the first emerging officer shot Tamir dead. In the blink of an eye.

Tamir Rice was shot twice from less than 10 feet.

Back in 2014, as I watched the footage of Tamir Rice’s murder, I wondered then, why did the the cops mount the curb? Why did they bypass the pavement and careen the patrol car onto the grass? Into the park? Why the frantic invasion of a place for play and recreation? Why, given the clear lines of sight (evident both in this photo and in the murder footage) from a good distance away, did they not approach slowly and with caution?

“This court is still thunderstruck by how quickly this event turned deadly,” wrote Ronald B. Adrine, Cleveland Municipal Court Administrative and Presiding Judge in an Administrative Order on the case. “On the video, the zone car containing Patrol Officers Loehmann and Garmback is still in the process of stopping when Rice is shot.”

Misinterpreting a situation and mistaking a toy for a gun (in the case of Tamir Rice) — or mistaking anything handheld, or any motion toward a hip or a pocket (in the cases of thousands of others) — is the defense to which law enforcement turns repeatedly and, calamitously, the one which almost always exonerates them of their crimes.

This is a photo made by Alanna Styer. It is part of the project Where It Happened for which Styer visited and photographed 54 sites where people of color were slain at hands of law enforcement. In 2016, The Guardian reports, 1,093 people were killed by police officers in the United States.

“That is an average of three people a day,” writes Styer. “The incidents detailed in my archive span 50 years, from 1965 to 2015. This book documents only 54 of the tens of thousands of deaths that have happened over those 50 years.”

Mostly, the locations and details of those thousands of deaths aren’t known beyond the memory of friends and family, the accounts of the cops involved, and the reach of an investigation … if one occurred. Even then, the details remain contested. The majority of the places in Where It Happened are new to us, the audience. But Styer’s photo of the gazebo at Cudell Recreation Center is not new. It’s power rests, for me, in the fact that I have previous familiarity with the place through the news coverage and activism in the aftermath of Rice’s murder. I recognize the site. You probably do to. We might also recognize the site of Michael Brown’s death on that tarmac road with verges of short, thinning grass. We may recognize other sites of avoidable killings that made it to our news feeds and memory. We don’t, regrettably, recognize the vast majority of the tragic theaters to which Styer’s work speaks. There are too many.

Styer’s photo shifts our vantage point from the elevated view of the CCTV across the street and down to street level. Whereas previously the benches and the posts were rendered in the indistinguishable and out of focus action of the footage, they’re now brought into sharp focus. We see the underside of the gazebo roof, not the top. We’re provided a perspective from the asphalt where the cop car could have and should have been.

Being “in” this image, I only want to get out, of course. A world in which this wasn’t a murder site and you or I didn’t recognize it as such would be, inarguably, a better world. Specifically, I want to step back. The unnecessary haste with which officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback charged into this scene gloms onto this image. That unfathomable CCTV footage is this photo’s frame.

Loehmann and Garmback’s excessive urgency which escalated the event from zero to murder perverts Styer’s image. But it also makes it. This photo works upon and within the collective exposure we’ve had to that grainy footage. Styer’s tribute here isn’t working in isolation but in extension of previous visual feeds to which we’ve all been audience. This image is an intervention and it works to disrupt our (possibly passive) consumption of death. It revisits the space and time of an event in which Tamir Rice had, essentially, no agency. The stillness is terrifying. True, the image could be read simply as a visual description of a memorial but I argue that precisely because it grounds us between the CCTV camera and Rice’s swift execution, the photo re-activates both the event and our relation to it.

Acts of police brutality (or citizen brutality, e.g. George Zimmerman against Trayvon Martin) frequently spurn a battle of images — calls for the immediate release of dash cam footage; calls for body-cams; different photos are circulated and cast as sympathetic, or not, to the victim and the perpetrator; media outlets trawl the social media feeds of victims, perpetrators and associated individuals. Whether conscious or not, Styer is reacting to such frenzies. She is paying homage to the victims, months or years after the news story has passed and the casket lowered. Where It Happened is a dark type of pilgrimage but I feel Styer is making it in good faith and I argue she’s returning with images that are a positive contribution. Google Street View does not make imagery that is conscious or respectful (interestingly, it hovers above street level like CCTV, delivering a detached record). Cellphone images may carry as much, if not more, respect as Styer’s photographs and this might be based on a personal connection to the victim, but those amateur images are not made by an artists intent on publicly disseminating them and talking about the issues that forged them.

I admire and have reported on Josh Begley’s project Officer Involved which uses code to automatically render both satellite and Street View images of sites of deaths involving law enforcement. Thousands of sites. While the subject is the same Styer’s work is considerably different in tone and effect. If Begley manages to remind us of the scale of the problem then Styer’s work reminds us to recognize each depressing part of the problem. I can’t code or manipulate Google Maps API but I can walk, bike or drive to killing sites within my own city. Styer’s practice takes time and effort, away from the screen. In 2015, Teju Cole reflected upon the problem of the constant visibility of death. In Death In The Browser Tab, Cole recounts his discomfort with only *knowing* the death of Walter Scott through the infamous footage made by passerby Feidin Santana who was hiding in the bushes. Cole had the opportunity to visit North Charleston and with a friend he found the parking lot of Advance Auto Parts on Remount Road in which Officer Michael Slager first stopped Scott. Then Cole traced the steps of them both to the park in which Scott was slain.

“[…] being there also revealed, in the negative, the peculiarities of the video,” writes Cole, “peculiarities common to many videos of this kind: the combination of a passive affect and the subjective gaze, irregular lighting and poor sound, the amateur videographer’s unsteady grip and off-camera swearing. Taken by one person (or a single, fixed camera) from one point of view, these videos establish the parameters of any subsequent spectatorship of the event. The information they present is, even when shocking, necessarily incomplete. They [videos] mediate, and being on the lot helped me remove that filter of mediation somewhat.”

Styer’s practice is one response to the problematic mediation that Cole describes. Few of us can identify the problem, let alone respond to it. And just as Cole felt better for mindfully visiting the site of Walter Scott’s death, and just as Styer was compelled to visit 54 catastrophic sites, we can choose to seek out a different image. Away from local TV news and social media, death might become less abstract? The sheer scale of the issue might become overwhelming. It is. But are we citizens that feel or do we just talk about what it is to feel?

Are we inured and numbed by murder on our screens? Or are we compelled to act because of it? We can all easily research the institutional violence in our communities. Maybe some of us might be compelled to make pilgrimages of our own and to carve out time to think about the violence that always plays out on our streets before it is broadcasted into our homes. Styer took the time and she has mediated at these sites. Her image of the gazebo in which Tamir Rice was shot and killed gave me the opportunity to mediate. I am grateful for that.

Sometimes photographs are about what’s literally depicted. Sometimes the lessons in photographs are in the method by which they were made. In Where It Happened it is both.

–

Alanna Styer is currently crowdfunding a book of images from her series Where It Happened. Please consider supporting the production of the photobook, titled No Officers Were Injured In This Incident, by visiting Styer’s Kickstarter page.

Listen to a radio interview with Styer about the project and her goals for the book.

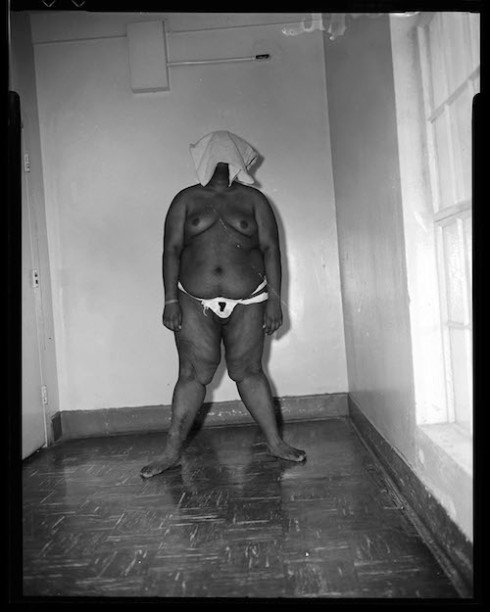

Richard Wayne Jones was convicted and sentenced to death for the February 1986 kidnapping and murder of Tammy Livingston in Hurst, Texas. Photographed on Aug. 2, 2000, executed Aug. 22, 2000 (AP Photo/Brett Coomer)

–

Rian Dundon, photo editor at Timeline, has pieced together 20 years of Texas Death-Row Portraits, a photo-gallery depicting some of the men executed by the state of Texas since the early eighties. The images are made by a host of photographers down the years working for the Associated Press (AP).

“As the only non-local news organization with a guaranteed seat at every execution, the AP is granted special access to prisoners, and as a result the agency has accumulated an unusual set of portraits made shortly before inmates’ executions,” writes Dundon.

Never intended to be seen in aggregate, Dundon argues that the portraits assume a weight and significance when brought together. Prisons are a time capsule so regardless of who is shooting, the visiting booths, prison issue uniforms, standard spectacles and prisoners’ pallid skin are constants throughout. The lighting is artificial adding to the sense of unnaturalness in which the subject and photographer operate. Dundon makes comparison to lauded photographers of our time.

“The portraits are uncanny for a wire service. Eerily intimate, carefully composed. There are echoes of Robert Bergman or Bruce Gilden,” he writes.

If art exists here, I’d argue it is not in the individual portraits per se but in Dundon’s grouping. A whole greater than its parts. Looking into the eyes of these condemned men provides a view into the soul of a nation. Here’s a gallery of American vengeance. An album devoted to violence in response to violence.

I wanted to share with you an essay I wrote for the publication that accompanied Demos: Wapato Correctional Facility a project by artist collective ERNEST at c3:initiative, in Portland, Oregon (September 2015).

The essay, titled Never Neutral, considers the drawings of one-time-California-prisoner Ernest Jerome DeFrance. I wander and wonder one way and then the other. For all their looseness, DeFrance’s drawing might be the tightest and most urgent description of solitary confinement, we have. They come from down in the hole.

Pen marks rattle around on the page like people do when they are put in boxes.

I ventured away from photography here. Got a bit speculative. Have a read. See what you think. See what you see.

NEVER NEUTRAL

Power breeds more power. The unerringly-certain power belonging to, say, nation states, financial posses, military strategists and total institutions, rides roughshod over opposition. The assault upon bodies, ideas and ecology inherent to the process of accumulating power is not always a conscious assault. As a power grows, opponents shrink, relatively. Harder to acknowledge, and even see, opponents that recede from power’s view are easier to crush.

Prisons have crushed their fair share. For the past four decades, the United States’ prison systems have grown exponentially. They have, at times, and in some places, grown unchecked. Since 1975, the number of prisoners has increased five-fold (and the number of women prisoners increased eight-fold). The U.S. spends $80 billion annually to warehouse 2.3 million citizens. In any given year 13 million individuals are cycled through one jail or prison or another. The prison industrial complex has come to dwarf education budgets. It has, in California, battered teachers unions. It removed non-custodial sentencing policy from the table for many a long year. It disavows notions of treatment, restoration or forgiveness. The prisons industrial complex laid to waste many of the key social, moral, political, environmental and psychological underpinnings of community.

In the face of such tumorous growth, common-sense opposition has been edged out and swallowed up. Sporadically, however, narratives that counter the fear, bullying and rhetoric of the prison industrial complex and its beneficiaries capture attention — narratives from advocacy, journalism, personal correspondence, legal briefs, FOI requests, jailhouse law, contraband and whistleblower testimonies. Art, too, has consistently spoken—or sketched—truth to power. Art is part of the resistance.

Prisoner-made art is, mostly, made for loved ones beyond the walls; prison art rarely gets seen by anyone beyond its intended recipient.

Given the sheer volume of jailhouse artworks made every day, it may seem strange to isolate, for this essay, a single prisoner’s sketches for critique. There is, however, something profound in the works of Ernest Jerome DeFrance that set them apart. Prison-art (pencil portraiture, greeting cards, DIY-calligraphy, envelope doodles) tends to reveal the circumstances of its production; that is, it reveals the facts and parameters of the prison system (limited resources, distant recipients, censor-safe subject matter).

A lot of prison part is personal and figurative, but DeFrance’s work is abstract, loose and reveals not only the circumstances of production but the brutalizing effects of those circumstances. For example, a run-of-the-mill prisoner-drawn portrait of a child — and the hope it may embody — is made in spite of the system, and a child’s innocence is something outside and beyond any corrupted system. Removing sentiment from the equation, a prisoners’ card for her child is an established, safe, non-controversial, and relatively unpoliced gesture. By contrast, DeFrance’s drawings operate outside of the routine prison art economy; they are untethered, non-figurative and non-occasional statements that are difficult to anchor and understand.

DeFrance’s loops and swirls are the feedback of a maddening prison system.

DeFrance made these images while incarcerated in the California prison system. During that time he spent extended periods of time in solitary confinement. He submitted these works to Sentenced: Architecture and Human Rights (UC Berkeley, Fall 2014) an exhibition produced by Architects, Designer and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) an anti-death penalty group that also argues against prolonged solitary confinement.

Architect Raphael Sperry, founder of ADSPR, led a highly visible media campaign for the adoption of language in the American Institute of Architects code of ethics prohibiting the design of spaces that physically and psychologically torture — namely, execution chambers and solitary confinement cells. Why? Because extreme isolation can lead to permanent psychological impairment comparable to that of traumatic brain injury. [1]

In an attempt to reconnect the most isolated American citizens with the outside world and in order to get some reliable information about solitary confinement, the call for entries for Sentenced: Architecture and Human Rights requested drawings of solitary cells by prisoners in solitary cells. Of the 14 men who submitted work, most stuck to the brief and drew plans or annotated elevations. DeFrance sent dozens of frantic nest-like lattices.

I defy anyone to say that DeFrance’s works don’t encapsulate the same terror as the to-scale, measured, line-drawn renderings by fellow exhibitors. It is not even clear if DeFrance had completed these works. What is complete? What is a start and what is an end … to a line, to a thought, to a stint in a box when the lights are always on, the colors are always the same, and sensory deprivation perverts time, taking you outside of yourself?

Solitary confinement “undermines your ability to register and regulate emotion,” says Craig Haney, psychology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “The appropriateness of what you’re thinking and feeling is difficult to index, because we’re so dependent on contact with others for that feedback. And for some people, it becomes a struggle to maintain sanity.” [2] Chronic apathy, depression, depression, irrational anger, total withdrawal and despair are common symptoms resulting from long-term isolation. [3]

All we know is that DeFrance considered these works finished enough to mail out.

Like a Rorschach Test for the horror-inclined, DeFrance’s works trigger all sorts of associations — Munch’s The Scream, Mondrian’s trees, Maurice Sendak’s darker side, Pierre Soulages‘ everyday side and Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away character No Face. I can go on. There are knuckles, clenched fists, scarecrows and magic carpets. I see bulging eyes. I see that optical illusion of the old witch’s nose. Or is the neckline of a young woman in necklace and furs?

Reading into DeFrance’s art with ones own visual memory is, admittedly, an exercise fraught with complications. Scanning work for something familiar is to lurch toward inner-biases. How does one land, or explain, connection with this work?

DeFrance’s art defies easy definition. These are not the crying clowns, the soaring eagles, the scantily-clad women or the Harley Davidson cliches common of prison art. These are … well … you decide. Faces, collars, cliffs, ropes, cliff faces, tourniquets, capes and caps? Is that a helmet? Of a riot cop? Of a cell-extraction specialist? Of the law and that which metes out judgement, retribution, pain and accountability? Or is it a divine shroud? Or is it a torture hood? [4]

On any given day in the United States, 80,000 people are in solitary. In California, solitary is a 22½-hour lockdown in a 6-by-9-foot cell with a steel door and no windows. Juan E. Méndez, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, told the UN General Assembly in June 2011 that solitary confinement is torture and assaults the mental health of prisoners. “It is a harsh measure which is contrary to rehabilitation, the aim of the penitentiary system.” Mendez recommends stays of no more than 15-days in isolation. Preceding this, in 2006, the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America’s Prisons, a bipartisan national task force, recommended abolishing long-term isolation reporting that stints longer than 10-days offered no benefits and instead caused substantial harm to prisoners, staff and the general public. [5] Some Americans have been in solitary for 15, 20, 25 years or more.

If a drawing “is simply a line going for a walk” like Paul Klee said then DeFrance’s drawings pace and circle the paper as he would his 54 square feet. One’s eyesight deteriorates rapidly in solitary. Denied any variation in depth-of-field, sharpness and acuity are lost. In a state of looseness and unknowing, gray walls throb and the mind conjures its own forms. Amorphous beings pulse within DeFrance’s work. Solid shape abandons us. Are we looking at shadows of ghosts? Scale suffers too. These forms are as large as you are brave enough to imagine.

Inasmuch as these images are indicative of solitary confinement experience, they are indicative of all prisons in the United States. “Every terrorist regime in the world uses isolation to break people’s spirits.” said bell hooks in 2002. hooks was talking about social exclusion but the phrase applies as easily to physical confinement. Indeed, with the exception of total-surveillance enclaves (where control needn’t be material) social exclusion and extreme incarceration tend go go hand-in-hand anyway. DeFrance’s works are a commentary, from within, of the philosophy and architectures we’ve perfected as an ever-more-punitive society. No other nation in the world uses solitary to the degree the United Sates does, and no other civilization in the history of man has locked up as greater proportion of its citizens. [6]

“Solitary confinement is a logical result of mass incarceration,” said Dr. Terry Kupers, psychologist and esteemed solitary specialist. [7] The demand for cells to house those handed harsher, longer sentences resulted in a huge prison boom since 1975. Still, these facilities could not adequately accommodate the vast number of people being locked up. Overcrowding gripped all states and any mandates to rehabilitate and provide activities for prisoners were all but abandoned. Haney reasons that extreme isolation resulted directly from prisons attempting to maintain power. He says, “Faced with this influx of prisoners, and lacking the rewards they once had to manage and control prisoner behavior, turned to the use of punishment. One big punishment is the threat of long-term solitary confinement.” [8]

Kalief Browder’s suicide in June 2015 brought national attention back to the issue of solitary confinement. He was kept in Rikers Island for 3 years without charge for an alleged theft of a backpack. Kalief didn’t kill himself, a broken New York courts and jail system did. [9] Ever since the California Prison Hunger Strikes, beginning in 2011, solitary had been the main topic on which to hang debate about mass incarceration and criminal justice reform. The unforgiving logic of solitary confinement policies is the same as that which has led to thousands of in-custody deaths, so-called “voluntary suicide” and officer-involved killings.

The Black Lives Matter movement has successfully tied over-zealous community policing, to stop-and-frisk, to restraint techniques, to custody conditions, to a bail system that abuses the poor, to extended and unconstitutional pretrial detention, and to solitary confinement in its devastating critique of a structurally racist nexus of law enforcement.

#SayHerName. Sandra Bland in Waller County, Texas; Jonathan Saunders in Mississippi; Tamir Rice in Cleveland; Charly Leundeu Keunang in Los Angeles; Sgt. James Brown in an El Paso jail; James M. Boyd in the hills of Albuquerque; John Crawford III in a WalMart in Ohio; Walter Scott in North Charleston; Eric Garner and Akai Gurley in New York; Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; and thousands of more people over the past 12 months alone killed by law enforcement.

So corrupted and violent is the prison system that one wonders if it can be fixed at all or whether it should be completely disassembled. Neil Barksy, chairman and founder of The Marshall Project, recently argued for the total closure of Rikers Island [10]. I am often asked if I think there exists people who deserve to be locked up and should be locked up. There’s a presumption in the question that the prison is a neutral factor. And there is a presumption, too, that people don’t change. But a prison is never neutral. In fact, most of the time prisons are very negative factors int he equation. Prisons damage people severely. Mass incarceration has made us less safe, not more safe. At what point and in what places can we confidently state that a prisoner’s violence (or the threat of violence that is attached upon them) is his own?

Conversely, at what point must we accept that the prison itself has caused anti-sociability and incorrigible behavior? Why are we surprised at the notion that a system built on threat and violence creates prisoners who incorporate threat and violence into their survival? Prisons create, often, people who fit better in prison than in free society — most end up institutionalized and docile and a few violent and unpredictable. Ultimately, no one can pass judgement on a prisoner because when hundreds of thousands of men, women and children are serving extremely long sentences or Life Without Possibility Of Parole, they exist in a system that molds them to our worst assumptions.

How far are we willing to go to protect ourselves against our worst fears and demons of our own creation? The first of many things I saw when viewing DeFrance’s was an echo of Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son. According to Roman myth, Saturn was told he his son would overthrow him. To prevent this, Saturn ate his children moments after each was born. His sixth son, Jupiter, was shuttled to safety on the island of Crete by Saturn’s wife Ops. Unwilling to surrender his absolute power, Saturn lost his mind. Goya is one of many artists to depict the scene, but none did it with such gross frenzy.

Goya had watched the Spanish monarchy destroy the country through arrogance. In his despondent old age, Goya reflected upon the darker aspects of society and human condition, and he played with notions surrounding power and the way a power treats it’s own charges. The prison industrial complex devours humans. It relies on bodies. Private prison companies forecast profits based upon toughening legislation to fill their facilities. Our laws have looked to warehousing instead of healing, and our society has travelled too far, for too long, into territories of massive social inequality. Art is part of the resistance and sometimes exposes a system that is programmed to deny witness; sometimes art can give those outside prisons a glimpse of the torture inside.

To see Ernest Jerome DeFrance’s art is to look into the belly of the beast.

FIN

–

–

FOOTNOTES

[1] Atul Gawande, ‘Hellhole‘, New Yorker, March 30, 2009.

[2] Craig Haney, ‘Mental Health Issues in Long-Term Solitary and ‘Supermax’ Confinement‘, Crime & Delinquency 49 (2003). ps. 124–156.

[3] Stuart Grassian, ‘The Psychiatric Effects of Solitary Confinement‘, Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 22 (2006). p.325.

[4] The four men in charge of reconstructing Abu Ghraib for US military use were hired shills who had overseen disfunctional and scandal-ridden departments of correction the U.S. in the decades prior to 2003. Abu Ghraib was not an abnormal situation; it was a reliable facsimile of the abusive systems routinely in operation in the homeland. They four men were Lane McCotter, former warden of the U.S. military prison at Fort Leavenworth, former cabinet secretary for the New Mexico DOC, John Armstrong, former director of the Connecticut DOC. Terrry Stewart, former director of the Arizona DOC and his top deputy Chuck Ryan. View more at Democracy Now!

[5] Confronting Confinement [PDF] Commission on Safety and Abuse in America’s Prisons:

[6] For many reasons, the widespread use of isolation in American prisons is, almost exclusively, a phenomenon of the past 20 years. Some prisoners have been kept down in the hole for decades. The controversial use of long-term solitary confinement is one of the most pressing issues of the American prison system currently in public debate. Much of the debate results from the attention drawn to California—and to the SHU at Pelican Bay in particular—by the California Prisoner Hunger Strike.

[7] Terry Kupers, in the keynote address at the Strategic Convening on Solitary Confinement and Human Rights, sponsored by the Midwest Coalition on Human Rights, November 9, 2012, Chicago.

[8] Brandon Keim, ‘Solitary Confinement: The Invisible Torture‘, Wired.com

[9] Raj Jayadev, founder of Silicon Valley Debug and pioneer of Participatory Defense makes this argument very well.

[10] Neil Barksy, ‘Shut Down Rikers Island‘, New York Times, July 15, 2015.

–

WORK DETAIL

At the back-end of 2011, I paid a visit to Nigel Poor and Doug Dertinger at the Design and Photography Department at Sacramento State University where they both teach. We talked about a history of photography course that Nigel and Doug co-taught at San Quentin Prison as part of the Prison University Project. At the time, there was no other college-level photo-history course other class like this in the United States. I have no reason to believe that that has changed (although I’d happily be proved wrong — get in touch!) We cover curriculum, student engagement, logistics, and the rewards of teaching in a prison environment.

Toward the end of the conversation we move on to discuss an essay by incarcerated student Michael Nelson. It was a comparative analysis between a Misrach photo and a Sugimoto photo. The highly respected TBW Books recently released Assignment No.2 which is a reissue of Michael’s essay. Packaged in a standard folder and printed on lined yellow office paper, Assignment #2 caught the photobook world a little off guard. Reviewers that dared to take it on admitted to being flummoxed a little. And then won over.

Back in 2011, TBW’s interest hadn’t yet been registered and Poor was still in production of the audio of Michael reading the work for public presentation. TBW Books publisher Paul Schiek has talked about the production of Assignment No.2, but Nigel Poor less so. This is the back-story to one of the most unique photo books of recent years — a book that combines fine art and fine design with an earnest recognition of a social justice need.

–

Scroll down for the Q&A.

–

Q & A

PP: How did you come to teach at San Quentin?

Nigel Poor (NP): I was always interested in teaching in a prison, and I just really never had the time to do it. While I was on a sabbatical [in 2011] I got an email from the Prison University Project saying they were looking for someone to teach art appreciation. I thought it would be a perfect time to teach there and form a class around the history of photography. I really wanted to do something with Doug so we got together to write this class.

PP: What do you look at?

NP: The history of contemporary photography — focusing on the 1970’s to the present. The course is 15 weeks like a regular semester. We met once a week for three hours. We started with early photographers — August Sander, Walker Evans and Robert Frank just to put some context and talk about how these photographers are often quoted and we move forward and show people like Sally Mann, Nan Goldin, Nick Nixon, Wendy Ewald.

Doug Dertinger (DD): Nigel tended to teach about the photographs that dealt with people, portraits, and social issues. My photographs tended to be the ones that dealt with land use and then also media. We struck a nice balance.

DD: The first two classes were strictly on aesthetic language, form, how to experience images, how to talk about them. The first assignment asked them to describe a photograph that doesn’t exist, that they wished they had that would describe a significant moment in their life. In that way they would create a little story for us and we would get to know something about them but they’d also have to use all the language about how you talk about a photograph. It was a really wonderful way to get them to think about making themselves part of the story of the photograph. Even if a photograph isn’t about you, you can bring your experience to it. It’s not solipsism; it is a way of entering photography. The exercise allowed them to take emotional chances with photographs.

In later classes, in 2012, Poor printed out famous photographs on card stock and asked her students to annotate directly upon the images. Click the William Eggleston analysed by Marvin B (top) to see a larger version of it. Kevin Tindall analysed Lee Friedlanders’ Canton, Ohio 1980 (middle), and Ruben Ramirez looked at David Hilliard’s tripychs (bottom).

–

PP: Were there any issues with your syllabus? Did you have to adapt it? Omit anything? Compared say to here at Sacramento State?

NP: I always tell my students, wherever we are, that it is an NC-17 rating. I naively thought I could just show the same images in San Quentin [as at Sac State] but when we started going through the process we were told that we couldn’t show any images that had to do with drugs, violence, sex, nudity, and children. Which is about 95% of photography!

At that point, I wasn’t quite sure how that was going to work but Jody Lewen [Director of the Prison University Project] is an incredible advocate and she didn’t want to presume censorship — Jody wanted the burden of explaation as to why we couldn’t show a particular image to be on the officials of the California Department of Corrections. She set up a meeting with the with Scott Kernan, the [then] Under-Secretary of the California Department of Corrections, and the [then] warden of San Quentin Prison, Michael Martell.

Kernan and Martell wanted me to show all the images that I was using for the class. I basically give them a mini-course in photography from 1970 to the present. We talked for close to two hours. I ended up getting permission to show everything except for four images.

PP: Not the worst case of censorship then?

NP: No. It was kind of a triumph. And, it must be said, without their help — especially Scott Kernan — I don’t think we would have gotten the class in.

PP: Can you describe the philosophy for the course?

NP: The central idea is to expose students to photography but really ask them to think about it quickly in an accessible and emotional way. Nor Doug or I teach from a theoretical or academic point of view. We argue that the images exist and they come to life because of the conversations we have around them. Students learn basic things about framing, form, content, but I really want them to explore all the areas of the photograph.

At the beginning, I describe the photograph as something akin to a crime scene; we are detectives trying to piece all the visual clues together to uncover subtext — perhaps, even secrets of the images that maybe the photographer isn’t even aware of.

In 2012, Poor was shown an archive of 4×5 negatives of photographs made by the prison administration in the 70s and 80s. The amount of information attached to the images is minimal. Poor broke the archive into 12 loose categories. One from the ‘Violence & Investigations’ category (top) and one from the ‘Ineffable’ category (bottom).

–

PP: Let’s come back to that. Because I want to bring Doug in here. Doug, what did you think when Nigel asked you to co-teach this program inside San Quentin Prison?

DD: I thought great. My parents are doctors and spent the last five years of their careers teaching at Federal Prison System. I taught in prison back in 1993 — one summer just general education stuff. So, when Nigel said that she was going to do this, well, I knew I wanted to partner with Nigel and thought it would be fun, in a way, to see what the what’s going on inside San Quentin.

PP: How do these students fair compared to your students in *free* society?

NP: They really understand the power of education and the importance of being present. I never had a student fall asleep at San Quentin or look at me with that blank expression! They were so hungry, open to conversation. It makes you worry about finding that same intensity outside of the prison setting.

DD: The men they already knew what they were about in a sense and so they came to the class with questions about photography and they understood that photography could reveal the world to them in ways that they were hungry for. A lot of students that I’ve had outside are still trying to figure out what they’re about and they haven’t yet come to their own necessity.

And, some of the men [in San Quentin] somehow understood that learning to talk about images, learning to see the world in a more complex way, could actually change them. I wish there was a way that didn’t sound trite to explain it but I could see transformations in them from the conversations that we had. Every Sunday when I left teaching there I would drive home in silence just contemplating the conversations that we had and how I felt I was becoming a better person for spending time with them. I would like to humbly think that they were too. It was a real back and forth.

Was it Wordsworth that said the imagination is the untraveled traveler? It seemed like when we went to class we all went on these journeys that were very significant for all of us. They were ready to travel.

In Nigel’s final class, she asked her students to annotate on print outs of photos from the newly discovered prison archive, in a manner similar to that they had with famous photographs from the art historical canon. Above are two examples.

–

PP: Earlier you mentioned Sally Mann. I presume a photographer that the authorities think is controversial, a photographer that wider society considers controversial and divides opinion. How did the discussion about Sally Mann’s work pan out?

NP: Some of them definitely had questions about the intent: Why would the mother want to photograph her three children romping around naked on their beautiful farm? But what I wanted to talk about how those images are highly staged and stylized. They’re not documentary images of how her children grew up. They are images about maybe desire about childhood, maybe the photographer inserting herself very clearly into these images. What is Sally Mann saying about the complexities of childhood or how children do have sexual feelings and act out in various ways? The images are about creating a tableau in a sense. It isn’t just about this mother who may have made images that made her children uncomfortable; it’s about creating stages to talk about emotional states of being.

PP: Well, I would think that many of the students are interested in notions of fact, truth, whether you can trust an image. Apart from the body, ones word is pretty much all you have when you’re incarcerated.

NP: We had a discussion very early on about the image always being a fabrication. It’s one person’s opinion putting a frame around the world and we always have to keep that in mind whether it’s documentary work or artist’s work. A lot of them got upset about that because I think they wanted to trust that something was reliable and truthful.

NP: And that may reflect a little bit on what happens to them, as people give evidence, or they want to assert their innocence, or not necessarily their innocence but how something unfolded in their life — this idea that everything is flexible and fluid was a little bit unnerving at times. They couldn’t look at the picture and think that’s exactly what the photographer meant and a few of them got prickly about it. It would come up off-and-on, you know. Can we use the word truth in reality when we’re talking about images and then by extension can you use those words when you’re talking about your own experience?

DD: That was a continuing topic throughout the whole semester. It was interesting too that they I don’t know how to describe it but they knew when they looked at a picture that there were all these elements in there. They explained it to us once: They get one picture from home once every 6 months, they pour over every detail of it and the desire is to create a narrative that they can fully believe and fully immerse themselves in. It was hard for them to understand that at first, at least, that there could be five different opinions about what a photograph was and each one kind of had equal weight.

Detail of Assignment No.2. Courtesy TBW Books.

NP: We don’t have a truth to give [the prisoners]. We’re going to give them our experience and talk about how we see the pictures but we’re going to learn something from them by the way they interpret images. I would see a photograph in a different light, often, after I heard what they had to say about it. I was the teacher in the classroom but it was very much about the power of group conversation. You have to outline what you want to discuss but you never quite know where the conversation’s going to go and I think that gave them a sense of power.

DD: I wonder if it was us not being, in a sense, “guards of meaning” that allowed them to say, ‘Oh, Nigel and Doug can be trusted to be privy to what we think, and they’re going to let us say things, and they’re going to correct themselves in relation to what we’re saying. We can participate, we have equal voice.’

PP: What do your students have to contribute to society?

NP: Before you have an experience in prison as a teacher or someone who’s going in as a civilian volunteer, prisoners are a group of invisible people. Even though I think I’m a thoughtful person, I had assumptions from what I read in the paper, in movies, in news.

PP: What you saw in photographs?

NP: Yeah! That these are going to be scary men, that if you turn your back are going to hurt you, that they’re animals they need to be separated from us and that they’re one-dimensional.

PP: Not so?

NP: When you go in there and you start talking and you see that these are complex, fascinating, thoughtful people; they’re citizens. They are part of our society. Yes, some of them have done terrible things but we have to think about reform and education, and the huge issues of, yes, redemption and forgiveness. How do we deal with those things? I think the only way you can thoughtfully talk about rehabilitation and forgiveness and make change is if you have a personal experience in there — you’re going to change your mind.

Details of Assignment No.2. Courtesy TBW Books.

NP: We need to find ways to use what’s in there to contribute to our society — to tap their experiences and thoughts. I became a better person by going in there and spending time. I learnt what it means to be human.

PP: That is similar to the feedback that I’ve got from other educators who’ve worked in prisons. Do you feel you are a conduit to the outside world. Do you have an added responsibility to share these stories, to share these men and their experiences with the wider public?

NP: I’m a pretty shy person and sometimes it’s difficult for me to talk at parties or whatever. But, now, I call myself the San Quentin bore. All I want to do is talk to people about this amazing experience, what these men are like. I feel very strongly about it, it’s not about me; it’s about this world that’s veiled and it’s about these men that are made invisible.

PP: You are not only a teacher, you are now an advocate. I hear you’re about to give a student the opportunity to “present” his work to the public?

NP: One of the assignments we had for the students was to give them two images from by two different artists and to ask them to analyse them. The only things the student knew about the works were the artists’ names, the dates, and the titles.

One student, Michael Nelson was given an image from Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theater series and a Richard Misrach image of a drive-in theatre from his Desert Canto series.

Richard Misrach. Drive-In Theatre, Las Vegas (1987), from the series American History Lessons.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. La Paloma, Encinitas (1993), from the series Theaters.

NP: While Michael was doing the assignment he was put in the hole, isolation, segregation for four weeks. He wrote an amazing paper talking about those two images. So beautiful that I wanted to get it to Richard Misrach which I was able to do and Richard was blown away by the piece.

Richard had been invited to be part of an event in San Francisco called Pop-Up Magazine which invites 20 to 30 different artists, once a year, to tell six minute stories. Richard’s idea was to read the paper that Michael wrote which was incredible. BUT! Then we started talking about it more, the organizer of Pop-Up decided he wanted Michael to read the paper. So, I went into San Quentin and recorded him reading his beautiful paper.

PP: Fantastic.

NP: It will be edited together. Richard will introduce it, show the two photographs and then play the recording of the student reading. It’s thrilling that this man who’s been in prison for more than half of his life is going to have the chance to be heard by 2,500 people.

PP: Nigel, Doug, Thanks so much.

PP: Nigel, Doug, Thanks so much.

NP/DD: Thank you.

ASSIGNMENT NO.2 (2014)

In an edition run of 1000, Assignment No. 2 will give many more people the opportunity to experience Michael’s words.

By Michael Nelson, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Richard Misrach.

12 x 9.5″ closed / 12 x 30″ open.

20 pages.

2 full color plates.

All proceeds go to the Prison University Project.

Buy here.

–

Photo: Meghann Riepenhoff

I’m one of five jurors for this years annual juried show at SF Camerawork. Y’all should enter. Here’s the blurb …

CALL FOR ENTRIES: HEAT

This summer, SF Camerawork teams up with LensCulture to host our Annual Juried Exhibition. The theme this year is HEAT.

HEAT registers the volatility and restlessness that comes with long hot summers: violent crime rates increase, leases expire and people seek new homes, global weather changes signal an alarm, and warm summer days bring adults and children alike into the streets, parks, and beaches.

SF Camerawork invites artists to submit work that responds to HEAT: the social, political, and climatic conditions of rapidly changing environments. Following the lead of social and political advocates around the world, SF Camerawork asks artists working at all levels in photography to participate.

Art is politics. Particularly in the realistic forms of photography and filmmaking, what gets assigned, shown or sold reflects political considerations. […] Politics is in the air. All you need to do to get the message is breathe. – Danny Lyon.

Photo: David Butow

DETAILS

Deadline: Monday, June 15, 2015, 5pm PST.

Notification: Finalists will be contacted on July 1st.

Exhibition Dates: July 23 – August 22, 2015.

Opening Reception: Thursday, July 23, 6-8pm.

Application Fee: $50 application fee for up to 15 images.

ENTER NOW ON LENSCULTURE AND CREATE AN ACCOUNT TO UPLOAD YOUR APPLICATION

AWARDS/BENEFITS

EXHIBITION AT SF CAMERAWORK: 2-5 finalists will have a 4-week exhibition at SF Camerawork.

LIVE ONLINE REVIEW SESSION: Finalists will receive a one-on-one review with a juror through this innovative platform hosted by LensCulture.

20 JUROR SELECTIONS FEATURED: 20 juror selections will be exhibited on interactive screens at SF Camerawork as part of the exhibition.

FEATURE ARTICLE ON LENSCULTURE: Finalists will be featured in an article on LensCulture.

ONE YEAR MEMBERSHIP: All entrants will receive a one-year membership to SF Camerawork.

HEAT 2015 JURY

Pete Brook, Writer and Curator, Founder: Prison Photography

Jim Casper, Editor and Publisher, LensCulture

Seth Curcio, Associate Director, Pier 24 Photography

Janet Delaney, Artist and Educator

Heather Snider, Executive Director, SF Camerawork

QUESTIONS?

Please email info@sfcamerawork with “Call for Entries” in the subject line.

SF CAMERAWORK

Founded in 1974, SF Camerawork‘s mission is to encourage and support emerging artists to explore new directions and ideas in the photographic arts. Through exhibitions, publications, and educational programs, we strive to create an engaging platform for artistic exploration as well as community involvement and inquiry.

SF Camerawork is a membership-based organization.

1011 Market St., 2nd Floor

San Francisco, CA 94103

Gallery hours: 12:00 – 6:00 pm

Tuesday – Saturday (also by appointment)

415.487.1011

Photo: McNair Evans

HERE’S LOOKIN’ AT YOU

On March 1st, I was a panelist for the BagNewsNotes Salon The Lens in the Mirror: How Surveillance is Pictured in the Media and Public Culture.

In coordination with the Open Society Watching You, Watching Me exhibition, this online panel wanted to reflect not only upon surveillance in our society but how it is pictured and if those depictions meet the realities of networked viewing that are at constant play behind our walls,, systems, nodes and screens.

I felt like an amateur in the room with other esteemed panelists lining up thus – Simone Browne, Assistant Professor of African and African Diaspora Studies, UT Austin; Cara Finnegan (moderator) writer, photography historian, Associate Professor of Communication, University of Illinois; Rachel Hall, Associate Professor, Communication Studies at Louisiana State University; Marvin Heiferman, writer and curator; Hamid Khan, co-ordinator, Stop LAPD Spying Coalition; and Simon Menner, artist, and member of OSF surveillance exhibition.

Over two hours discussion, we discuss 10 images in turn. They flash up as we deconstruct their meanings, but it might be helpful to consult the gallery first, too.

Over the coming weeks, BagNews will be adding highlight clips for easier to digest morsels that get to the meat of our conversation.

“Surveillance technology permeates the social landscape,” says BagNews. “Tiny cameras monitor traffic, parking lots, cash registers and every corner of federal buildings. Through personal devices and social media, citizens also monitor one other.” In the highlight clip (above), moderator Cara Finnegan and panelists Simon Menner, Simone Browne, Hamid Khan, Rachel Hall and Pete Brook discuss generic imagery and the use of stock photography to represent this reality of daily life

SALON

The BagNewsSalon is an on-line, real-time discussion between photojournalists, visual academics and other visual or subject experts. Each salon examines a set of images relevant to the visual stories of the day often focusing on how the media and social media has framed the event. The photo edit is the key element and driver of each Salon discussion and great care is taken to create a group of photos that captures the depth and breadth of media representation.

Bearing Witness is a one-day symposium hosted by SFMOMA assessing the ways in which photography matters now more than ever. Loosely, the theme is connections. I will be presenting and I’m toying with some ideas surrounding the emergent trend in video visitation. Maybe. Possibly, I’ll retread safe ground and present the ideas that informed the recent Prison Obscura exhibition.

I’m on stage in the morning, I have been told. Bearing Witness is for one day only – Sunday 16th March. Speakers include David Guttenfelder, chief photographer in Asia for the Associated Press; Susan Meiselas, photographer, Magnum Photos; Margaret Olin, senior research scholar, Yale University; Doug Rickard, artist and founder of AMERICANSUBURBX; Kathy Ryan, director of photography, The New York Times Magazine; and Zoe Strauss, artist, Magnum Photos.

Organisers Erin O’Toole, SFMOMA associate curator of photography and Dominic Willsdon, SFMOMA Curator of Education and Public Programs, have posed these questions for the symposium:

Given the power and pervasiveness of photography in both art and everyday life, what is the significance of the rapid and fundamental changes that the field is undergoing? How have social media, digital cameras, and amateur photojournalism altered the way photographs capture the everyday, define current events, and steer social and political movements? How have photographers responded to these shifting conditions, as well as to the new ways in which images are understood, shared, and consumed? How have our expectations of photography changed?

Bearing Witness is preceded on March 14 and 15 by Visual Activism, a two-day symposium that explores relationships between visual culture and activist practices. Zanele Muholi is presenting at that, so not to be missed either.

DATE + TIME + LOCATION

10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. Sunday, March 16, 2014

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, 701 Mission Street San Francisco, CA 94103

TICKETS

Admission for both events is free, but it’s wise to register. The 500 spots for Bearing Witness have gone, but that’s always the case with over-zealous free-to-register-symposium-photo-enthusiasts isn’t it? Sign up for the waitlist and you’ll probably get in. I hope.

Image source: Toledo Blade