You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘A Dream Denied’ tag.

Xavier Randolph dances with his father Frank Randolph during a Hope House summer camp program for youth with imprison fathers at the North Branch Correctional Institution in Cumberland, MD.

RAYMOND THOMPSON JR.

Raymond Thompson Jr. is a photographer, video journalist, educator and father.

In his Justice Undone Project, Thompson Jr. documents the leaching and negative effects of mass incarceration. He shows us how the poor are criminalised by society and kept down. He’s trying to get past stereotypes of Black America and does so by photographing the families and the communities outside of prison. So far, chapters of Justice Undone include A Dream Denied and The Browns.

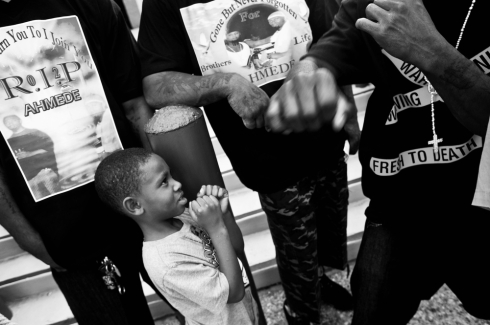

Prisons touch nearly everyone in America’s poorest communities. One person’s imprisonment effects many others’ lives. The knock-on effects are profound. Locked up, exiled parents can mean extended family members are the primary care givers. Young children can lack a mother or a father or both for long periods. A child’s emotional and social development can be hampered and the incarceration of a parent vastly increases a child’s chances of being locked up later in life. The cycle continues.

In film, print and photography, America has a history of demonising young black men. In response, Thompson Jr. works to image all generations and races from America’s lower classes in an attempt to build empathy in his audience. So far, Thompson Jr.’s work has focused on African American communities but soon he is to venture into poor white communities in the Midwest, and to demonstrate that our broken criminal justice policies impact the poor. Prisons are a class issue just as much as they are a race issue.

The closer you look at the prison industrial complex, the better you understand society. Thompson Jr. is holding up a mirror in which we are all reflected. He was kind enough to answer a few questions I had about his photography.

[Click on any image to view it larger]

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): It seems your work on issues surrounding community, the war on drugs and incarceration is an ongoing endeavour. Is this the case? If so, tell us what you’re up to and what you’re working on now.

Raymond Thompson Jr. (RTJ): My project Justice Undone started as my master thesis while I was in graduate school in Austin, Texas. I originally intended only to do a story about the long term effects of incarceration on families and communities in East Austin, which is a predominantly African American and Latino part of the city. After I received a grant from the Alexia Foundation to continue the project, I expanded the project to Washington D.C and New Orleans.

In the 18 months since then, my wife and I had our first child and I took a job working as a video producer for West Virginia University. So, most of the last 18 months have been consumed with adjusting to life as a parent. The sleep deprived nights are decreasing. So, I’m slowly moving into the next stage of this project.

Even though I have never been incarcerated and my immediate family has not been directly affected by mass incarceration, I still feel a deep connection to the issue. I saw myself in the faces of the men, women and children navigating the prison system. Now with the birth of my son, I feel it is even more important.

There are several story angles in my project that still need covering. I’m currently in the process of researching and planning local Justice Undone stories for trip this fall and a trip to the midwest in the early spring. I’m currently based in West Virginia, which offers a chance to approach this work from beyond the lens of race and move it more towards class.

A boy stares though a window during a Friends and Family of Incarcerated People (FFOIP) car wash fundraiser in Southeast Washington, D.C. Friends and Family of Incarcerated People, a non-profit based in Washington D.C., offers a summer camp for children of incarcerated parents and other children whose parents are absent.

Members of ‘Mix Emotion’ go-go band pray before a performance at a community gardening event in the Lincoln Heights area of Northeast Washington D.C. Lincoln Heights is a crime plagued area and has a large number of low-income residents.

Several D.C. teenagers relax and socialize during the Friends and Families of Incarcerate People annual retreat in outside Charlottesville, VA. The goal of the retreat is to give youth a chance to experience life outside of their depressed D.C. neighborhoods.

A child looks at a car that had been broken into the night before a Friends and Family of Incarcerated People (FFOIP) summer camp in Southeast Washington, D.C.

PP: When and how did you move toward your current political conscience?

RTJ: In the 1990s, I was a teenager living in the suburbs of Virginia outside of Washington D.C. I watched the War on Drugs rage on my television screen. It was in these moments that I started to feel something was wrong. But I was not equipped with the knowledge or maturity to understand what I was seeing. On my television screen, I watched images of black men and boys dead or being led away in handcuffs. These visual images negatively affected how I felt about myself and other African Americans. Part of the reason for working on Justice Undone is to heal myself and to start to reclaim the visual history of African Americans in the United States.

My political awareness stemmed from my undergraduate studies. I was an American Studies major with a concentration in human rights. In my course work, which spans from American literature and history to sociology, I learned to recognize the complex weave of racial, economic, and political threads that form the social blanket of America. But, what really set me on this path was a senior seminar on the American Prison Industrial Complex. That class expanded my thinking on the subject, which later became my intellectual basis for the project.

PP: How did you decide on strategies to talk about these issues with your photography?

RTJ: There have been so many images about prisons and about the War on Drugs. A lot of the pictures work to reinforce stereotypes about minorities as “The Other.” In the first part of this project, I focused on children and families left behind in mass incarceration’s wake. I felt I had to avoid images of black men in the beginning because I did not want viewers from outside of these communities to immediately write the project off. I needed those viewers to move beyond the stereotypes and to have a empathetic reaction, without relying too heavily on people being portrayed as victims. In the next stages, I will focus more on the men, who are actually directly affected by prison.

Many of the great documentary photographers of the past three decades have produced work that is great but also problematic because they reinforce stereotypical images of urban black life. One of those photography books I have on my bookshelves in Eugene Richard’s Cocaine Blue, Cocaine True. It is an important work, but if you don’t dive into Richard’s words that were published along with the images you can come away with a skewed meaning. It is this decontextualization that worries me.

My strategy to combat this decontextualization is to create images of black life that focuses on the everyday. By searching for images that show African Americans in the mundane ritual of daily life, I hope that people not directly affected by mass incarceration will be able to see themselves in the pictures the way I do, as an antidote to years of self-hate and willful ignorance.

The Booker T. Washington Public Housing complex, in Austin, Texas, is plagued by a revolving door of single-parent households and incarceration.

Nicholas Brown, 19, speaks with his girlfriend before leaving. He has a stained relationship with his mother Vicky who has spent the majority of his childhood away in prison and drug treatment institutions.

Marquis, 18, BB and Leroy Brown hangout on the front porch of Beverly Brown’s house in Austin.

Tyler Pippillion works on a math puzzle during a skills class at the African American Men and Boys Harvest Foundation, a non-profit in Austin, TX that works with at-risk minority youth.

PP: What are the main points you want to communicate in your work?

RTJ: The first thing I hope my audience gain from this project is that U.S. laws have been unequally enforced in poor minority communities. Second, I wanted to make understood that the large numbers of men and women cycling in and out of prison has an immeasurably negative effect on their communities. Finally, I want the audience to realize that the impact of incarceration is falling on small geographic areas within cities, because a large portion of these men and women are being taken from identified communities.

PP: Can you explain the title ‘Justice Undone’?

RTJ: I think that justice and fairness are central to the American ideology. If you follow the rules you will be rewarded. If you break them then you will be punished. For African Americans, The Civil Rights Act of 1964, was “justice” for generations of discrimination and abuse. But, the gains of the 1960’s were essentially rolled back by the War on Drugs, the tough-on-crime movement, three strikes laws, and drug sentencing laws, which unfairly fell on the shoulders of African American communities.

So the title is meant to reflect the havoc of three decades of drug policies and the resulting explosion of the U.S. prison population that has played a big role on the agency and self esteem of African Americans in the United States.

I wanted the title to reflect critically on the U.S. justice system, which has failed to protect its most vulnerable members. While I was writing and reporting for my masters thesis, I was inspired by the hip-hop song Tip The Scale from the Roots’ album Undun.

Lot of niggas go to prison

How many come out Malcolm X?

I know I’m not

Shit, can’t even talk about the rest

Famous last words: “You under arrest”

Will I get popped tonight? It’s anybody’s guess

I guess a nigga need to stay cunning

I guess when the cops comin’ need to start runnin’

I won’t make the same mistakes from my last run in

You either done doing crime now or you done in

I got a brother on the run and one in

Wrote me a letter, he said when you comin’

Shit man, I thought the goal’s to stay out

Back against the wall, then shoot your way out

Gettin’ money’s a style that never plays out

‘Til you end up boxin’ your stash, money’s paid out

The scales of justice ain’t equally weighed out

Only two ways out, digging tunnels or digging graves out

Through the lyrics of this song, I felt the frustration of many black men who have limited choices, but still must navigate the challenges of being a black male in the United States.

A boys listen to instructions on keeping a proper boxing guard during a rally to protest the shooting death of Almeded Bradley by an Austin Police Officer.

Boys play a game of basketball in the Booker T. Washington public housing complex, Austin, Texas.

Teenage boys play basketball at the Youth Study Center juvenile detention facility in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Chelsea Shorts set up a studio in a shed in the backyard of her east Austin home. She uses the space to make clothes, draw and paint. The shed is a refuge from the crowded house that she shares with her parents, grandparents, cousins and one sibling. Chelsea biological father was incarcerated for most of her life.

Beverly Brown covers her eyes as she rest in her living room. Members of three different generation of her family have been incarcerated or had problems with drug addiction.

PP: Is there an easy way to describe the massive effect harsher sentencing and imprisonment has had on communities you’ve documented. How, in other words, do we put it into words?

RTJ:There is no simple way to discuss the topic because it is so complex.

A lot has been put in words, but I don’t know if we have reached the same level of understanding in the visual. Part of my goal is to reimagine the image of African Americans in Americans’ visual memory. These days there is always public outcry at any sort of overt racial discrimination in words, written or verbal. There is a bit of a lag in the public’s response to visual stereotypes of minorities. Responding to these stereotypes and creating what bell hooks, calls the “oppositional black aesthetic,” is a way that image makers can help challenge mainstream biases.

PP: What can we do as audiences to photography and as citizens to improve the situation?

RTJ: The next time they see a newspaper article or a television news report about a drug arrest or a drug sentencing I hope they start a conversation with a friend of family member about what is happening in their name as taxpayers. I want people to see beyond the individual situation and start to see the overarching pattern of crime, punishment, drugs, and incarceration in America.

PP: How do you describe photography’s role in relation to social justice?

RTJ: I don’t know if social justice can happen in a visual vacuum.

Photography’s first purpose is to pass information about an issue to an audience. Its second purpose is to move the social conversation past exposition. There are details in the everyday that offer unique paths to understanding.

PP: And empathy.

RTJ: From the expression of someone’s eyes, to the color of a summer dress, to the chaos of a kitchen before serving Thanksgiving dinner. It is in those common areas that we as human beings find ways to related to each other. Photography as a quasi universal medium is perfectly suited for this task.

PP: Thanks, Raymond. And thank you for your work and conscience.

RTJ: Thank you, Pete.

Chelsea Shorts walks alone railroad tracks in Austin, Texas. Shorts father was incarcerated for most of her life.

BIOGRAPHY

Raymond Thompson Jr. is a freelance photographer and multimedia producer based in Morgantown, WV. He currently works as a Multimedia Producer at West Virginia University. He received his Masters degree from the University of Texas at Austin in journalism and graduated from the University of Mary Washington with a BA is American Studies. He has worked as a multimedia photojournalist for the Door County Advocate, the Times of Northwest Indiana, the Kane County Chronicle, Times Community Newspapers and the Washington Times.

You can follow his activities on his blog, on the Twitter and on Instagram.