You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison Photography’ tag.

Flicking through my old bookmarks, I was pleasantly bothered by bumping into the Corrections Photography Archive (CPA). This is a great small collection of prints organised by theme and location. Unfortunately, the online form doesn’t work so I can’t learn more about CPA just yet. I now the collection is larger than that number digitized for the interwebs.

A couple of my favourite groupings are Music (for fun) and Dining Rooms (which arranges itself as a Becheresque typology of prison food halls). In the end, I decided to use the collection twofold; 1) as counseling for myself, and 2) as a guarantee for the readers.

FROM THIS POINT FORWARD,

I PLEDGE NOT TO POST IMAGES OF RECEDING CELL BLOCK TIERS.

Regardless if the tiers recede to the brightest white or darkest gray. Regardless of the cause. When given a choice between a receding cell-tier-photograph and another, I will take the other. Let us exhaust this inevitable angle of all incarceration-based-photojournalism. Let us gloss over those photographs and move to the other images, which will be the ones to make the story anyway.

PURGE!

Official Blurb: The American Prison Society Photographic Archive records collection was acquired by the Eastern Kentucky University Archives in 1984 through the auspices of Dr. Bruce Wolford of Eastern’s College of Law Enforcement. Dr. Wolford received the photographs in 1979 from William Bain, instructor at the Kentucky Bureau of Training. In the 1960s Mr. Bain, a former staff member of the American Correctional Association, conceived the idea of a pictorial history of the American prison. With the aid of David A. Kimberling, a prison inmate and photographer, Bain had photographs copied from the American Correctional Association archives plus ones he received from various federal and state correctional facilities throughout the United States. In addition to the copies, which comprise the negative part of the collection, he acquired many original black and white photographic prints. Finally in 1978 through the work of Anthony P. Travisono, executive director of the American Correctional Association, Bain’s dream, The American Prison: from the Beginning. A Pictorial History, was published.

The photographic collection is rich in its depiction of early twentieth century prison life and conditions. The collection covers numerous subjects such as prison living conditions, recreational activities, industries, hospital care, corporal punishment, work gangs on the farm and quarries, vocational activities, weapons confiscated, prison architecture, and the death house. A few of the images are of prison officials, primarily in the federal penitentiary system.

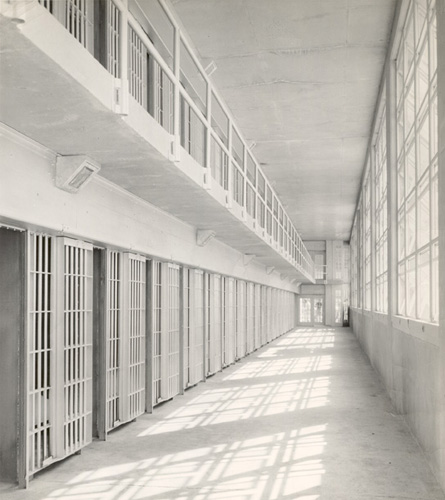

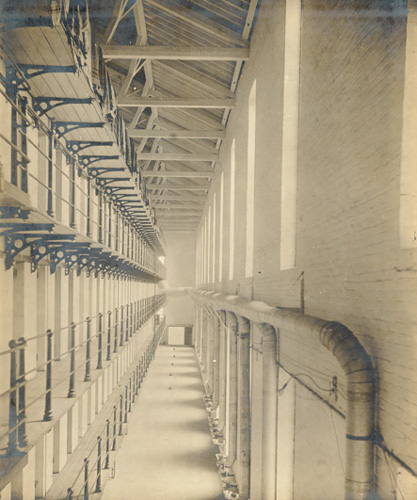

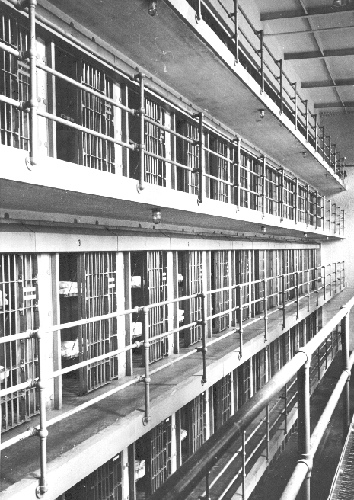

Images from Top to Bottom. All images courtesy of Corrections Photographic Archive

1. One of the cell corriders in the old penitentiary for males on Welfare Island. Note the distance of the cells from the outside walls and windows and the consequent limitations of light and ventilation, especially needed on account of the absence of toilets in the cells, 1924.

2. Isolation unit at Huntsville, Texas, 1953. Photo by Frank Dobbs.

3. Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Section of E.D.C.C.

4. Heating pipes in cell house at Indiana State Prison.

5. “A” block (North extension “outside cells”) 352 cells now used by Reception Center. Folger Adams Locking, December 5, 1946.

6. West cell block, Central Prison, Raleigh, North Carolina.

7. New Hampshire State Prison, portion of cell block.

8. No Information available.

9. Central aisle, Work House, Blackwell’s Island, New York.

Lloyd DeGrane‘s work is long-term and it is honest. DeGrane would like to see more transparency surrounding American correctional facilities, “I think people, taxpayers should see what they’re getting for their money”. I came across DeGrane in James R Hugunin’s 1996 curated exhibit Discipline and Photograph.

DeGrane carried out his Prison series between 1990 and 2001, when he photographed within the state maximum security Stateville Correctional Center, Illinois and Cook County Jail in Chicago. The three photos featured here each depict scenes at Stateville.

DeGrane took the time to discuss the role of photography in sites of incarceration, a photographer’s best approach, the names and labels given to him by inmates and images of the spaces between cells.

Did you await each photo opportunity? While working, were you alone or accompanied on the corridor or wing?

“I was usually escorted by a counselor – an unassuming, non-threatening person. Sometimes I’d go into a unit and walk around by myself, being careful not to get out of the view of a correctional officer. Stateville is a maximum security facility so some of the inmates were violent offenders. I talked to the inmates directly, sometimes going into their cells. For the most part the officials let me browse freely and talk to any inmates I wanted. Things, to a point, were pretty transparent. When I came into a unit someone would usually yell out my arrival”.

Isolation Unit, Stateville Correctional Center, 1992. Lloyd Degrane

What is happening in the Isolation Unit photograph?

“This is the isolation unit – I called it ‘the jail within the prison’. Inmates who committed an offense in the prison were taken out of the general population and held there 23 hours a day with one hour for outside exercise. That [the display of legs and arms] was the first reaction to me being on the wing”.

“The inmates, for reasons unknown to me, thought I was a state official of some kind. But, after I got to talking with a few people independently I was able to photograph several inmates with no problems, with the exception of one inmate who would try to throw excrement at the guards”.

Lockdown Protest, Stateville Correctional Center, 1993. Lloyd Degrane

Explain the situation here, with the trash and food on the floor.

“That was taken in 1993. Inmates were ending a five day lock-down and totally disgusted by the lunch served (cold baloney sandwiches every day). So, they threw the servings out of their cells onto the floor. The floor of the wing is commonly known as ‘the flag’.”

“Guards eventually had to clean it up. I noticed when I came back the next week that the roach problem was severe. I had to tuck my pant legs into my socks so the roaches wouldn’t crawl up my legs”.

Protective Custody Unit, Stateville Correctional Center, 1992. Lloyd Degrane

The interaction between the guard and inmate in the protective custody unit is fascinating – it melds contortion, humanity, routine and unlikely types for the prison environment.

“The inmate was in the protective custody unit. That’s a pregnant guard that’s looking at him. He didn’t have a mirror so the only way he could see what was happening outside his cell was to stick his head out of the food tray slot.”

Did the subjects of your images, specifically inmates, see the photographs after they were produced/exhibited?

“I always made a small photo for the inmates. Sometimes they got them and sometimes the warden or captain (for reasons I do not know) didn’t get around to giving them the photo. But, I was able to get a little deeper into the lives of the inmates that received photos.”

How do you work?

“The images are made slowly and carefully. No surprises. Observation and discussion with the inmates and then photos. That was my modus operandi. It’s like going into someone’s home, they know you’re there! So, it’s best to be respectfully curious. Some inmates wanted nothing to do with me (I think they had committed other crimes on the outside and didn’t want to be recognized). Other inmates didn’t mind at all. I talked with people all the time. I think taxpayers should see what they’re getting for their money. Transparency is key. But, many prison officials believe the opposite and in their facility, they rule!

Final thoughts on the prison system?

Prisons – and not correctional facilities (as the State of Illinois has named their institutions) – the concrete human warehouses behind razor wire are just that! Buildings that confine people. It’s an existential experience in a world that is both separate from America but a big part of the American economy. One sees homemade signs along Interstate 55 that read, ‘Don’t shut our prison down’, ‘Save the prison, Save our jobs’ outside Pontiac, Illinois, home to another maximum security facility that may close because of state budget cuts.

Don’t get me wrong though, some people belong in prison. I met many men who raped innocent women, killed children, beat other men to death for a few dollars and some who murdered their cellmates. I was glad that I didn’t meet them in a dark alley in Chicago. But, one thought that always went through my mind was, most of these people will get out some day. Will they change for the better or just be better criminals?

You kept an index of how the prisoners referred to you. It’s length, variety and contradictions reflect well the complexity of social experience within correctional facilities. Can you remind us of the index?

This is my index of how inmates referred to me. Picture Man, White man, The Man White Mother Fuckin’ Press Man, Black Gang Lover, Spic Gang Lover, White Prisoner Lover, Straight Dude Looking for Something – Policeman, The Photo Man, The European, The Springfield Connection, A Fair Man, An O.K. Photographer, An Artist, Homes, Homey, Fuckin’ Photographer, Homo, Fuckin’ Camera Man, The Camera Man, Inmate Lover, The Police, Friend and Cute Mother Fucker (The label given to me by Richard Speck).

I have been supremely busy lately. I have eight projects in various stages of draft, but want to throw up some quality images, accompanying words and give a general shout out to Bangladesh’s photographic community.

Through my day job, I am familiar with Shahidul Alam‘s fine photography. I am more impressed by his stewardship of his nation’s photojournalist community, here, here and here. It was at Alam’s Blog that I discovered the images of Momena Jalil. I’ll simply repost the photographs and let them and the text speak for themselves.

They were some 21 women. Some with with children who were free but had nowhere to go. So they stayed with their mother in captivity. It was a rare chance for us; it was the opening of the new women’s prison on eight acres of land situated on the Western edge of Kashempur. We were allowed because we were women and in those ten minutes we learnt what we could not have learnt in a lifetime. Losing one’s freedom strips us of the right to live. It is the strangest feeling, a chilling feeling. Freedom denied is freedom lost in the cradle of the life.

Cell, Momena Jalil, 2008. Having spent a year in prison already, 25-year-old Rahima still cannot reconcile with her living conditions.

‘It is difficult to cope with all that goes within the walls of a prison,’ she says. ‘There were times when the prison guards molested me…they do sexually abuse women,’ she says softly, hiding her face behind her white saree. As soon as the guards walk in her expression changes and she mutters, ‘we have no problems at all.’

From Jalil’s post it is obvious the system has affected the women very differently.

‘How can you not love the darkness, the stench, the suffocation and the crowds?’ asks fifty-year-old Khaleda in her raw husky voice. Her big eyes and rough expressions complement her loud and dominating voice. ‘After spending twenty-five years I don’t think I would ever want to go back. I get a taste of everything here – be it having tonnes of friends or being tortured, all of it is ‘fun’, she says sarcastically.

Khaleda knows the secrets of the prison, yet she refuses to speak up. ‘You know why I came here? My husband married another woman for no reason. He brought her home with her two children. I had done nothing. But he still did that. So I ate the two kids,’ she laughs aloud. ‘And then I got involved in a trafficking case and a lot more.’

In twenty-five years, Khaleda has seen the darkest sides of the prison. She has lived inside crumbled cells with no space to even sit or breathe. ‘I don’t like the idea of being moved to this new unit of the women’s prison. I love the people there. The Dhaka Central Jail is overcrowded, stinky, a torture hole but it’s still been my home for the past so many years,’ she says.

Khaleda is one of 200 women who are waiting to be shifted to the first female jail in Kashempur that recently opened.

She was a mother, a daughter, a sister, a home-maker, a beloved wife but today she is only a prisoner behind bars serving a life sentence. She could have been many things but situation, time, circumstance and fate took all her rights to live free in society. Society finds them unfit because they cross the line of the law; they were not born to be criminals but time took them where they committed crimes… some killed step-children, some were found trafficking in-between borders, they were too many and we had too little time to know what crimes they were in for. We had ten minutes, the guards were rushing us, it’s unthinkable to let journalists roam inside a prison. But we have been there, my colleague and I; we saw faces up close, people who live among us, their faces hold the rumours of sisters, mothers…

Two weeks ago I attended a talk by Van Jones, the founder of the Ella Baker Center. He advocates for social equality and the rights & opportunities of incarcerated youth. Recently, if he didn’t have enough on his plate, he has added saving the environment to his roster of causes. Jones’ energy is contagious and he quickly convinces you that there indeed is “one solution to our two major problems”.

Jarnail Basraa lines up solar cells for a solar energy panel at Evergreen Solar's headquarters in Marlborough, Massachusetts. After decades on the fringe, solar power is closing in on America's mainstream as surging fossil fuel prices and mounting concern over climate change spur states, businesses and homeowners into a quickening embrace with alternative energy. (REUTERS)

Hold on! What? Two problems? Aren’t there more problems than that? Yes, and so Jones, like President Elect Obama, argues that all these can be traced back to economics and environment. Furthermore, Jones argues for a single root solution to these two issues that solves the many related problems. Jones envisages a government-supported, corporate-boosted, people-activated Green Economy that shifts investment from “a 20th century pollution-based & consumption-oriented economy” to “a 21st century clean, solution-oriented economy”. The magic being that the jobless urban poor with the worst cases of asthma, cancers and pollutant-based health problems are the ones to take full advantage of this new platform. Jones asks, “Do we really want to further entrench ourselves in “eco-apartheid” in which the affluent retreat to the hills and the remainder suffer the smog?”

Jones admitted he is not the most likely of authors for a book of this type, but following quick inspection, it (and he) makes sense. Jones seeks routes out of poverty for the urban poor and the formerly incarcerated. His native California is more desperate for solutions than most states.

Solar panels soak up some rays near the Ironwood State Prison in Blythe, Calif. Last week, the state unveiled a 1.18 megawatt solar-power plant at the prison that provides enough electricity to power a quarter of the facility

Jones is thinking big. The creation of jobs, personal prosperity and regional economic growth would need to be unprecedented if it were to mop up the wasted lives and wasted dollars of the California Youth Authority & the CDCR let alone the gross deficit of California’s halting economy (For your interest I read that over 20% of California households owe more on money toward their mortgage than their house is actually worth).

It seemed that I had, accidentally, skirted the same issues Jones works with. How do you give enough previously disenfranchised people enough work and pride to reverse social histories of crime and transgression? If the state intervenes, prematurely or not, where friends and family cannot succeed, it absolutely must begin when the offender is committed to an institution. And yet, as I noted in my previous post only 5,400 inmates are involved in PIA work. (This figure doesn’t factor for the number of inmates in retraining programs, which fluctuates. I’ll get back to you) The fact remains, the CDCR is overcrowded and not investing in rehabilitation adequately. All education and vocational training is fully subscribed.

The unremarkable photograph (above) of the first CDCR solar field at Ironwood State Prison, which I wrongly attributed to Wasco, and used as for closing cynical footnote about watercolour painting is perhaps worth revisiting.

The fields are in the middle of nowhere, because most newly constructed prisons are in the middle of nowhere. I wonder if there could be a conspiracy of persuasion to bring SunEdison or any of their partners and competitors to these remote locations with an inactive but very willing pool of men, set up factories and operations and train inmates during their sentences?

I would like to ask Van Jones if he considers the current CDCR and/or the developing green economy infrastructure flexible enough to execute a long term retraining programme within California’s prison system. How plausible is it that the new green economy can benefit the imprisoned population of America? I believe Jones when he says we can reach out to the urban poor and provide training schemes. I believe Jones when he expects government support to launch thousands, even millions, of jobs and through doing so gives rise to a multitude of career paths that emerge, shape and change along with the renewable energy industry.

That said, I am skeptical that this herculean social project could dovetail easily with the federal and state prison systems of America. People are suspicious of corporations involved in state corrections; people may be shocked to inaction when learning of the massive investment and rarified leadership required for a large scale prison works programme; people know that historically the prison is hard to access; people may suspect no return on its tax dollars.

Logistically, anything is possible. But culturally many things are proscribed. The political will to enact a sweeping reform of prison training based upon a new-green-economy-doctrine may wither quickly when confronted with public opinion and economic depression. I fear prisoners will get ignored for another generation and pushed oncemore to the bottom of the priority list.

Google announced today that it has come to an arrangement with TimeInc to host the LIFE Archive. The archive is one of the largest collections in the world comprised of over 10 million images. This is an incredible new resource for photophiles worldwide. Twenty percent of the images went live today.

Carl Mydans. American flag draped over balcony of building as American and Filipino civilians cheer their release from the Japanese prison camp at Santo Tomas University folllowing Allied liberation of the city. Manila, Luzon, Philippines. February 05, 1945

A very preliminary search using the keyword “Prison” returned twelve pages of 200 images. I was struck by the strength of the handful of images from the Santo Tomas Prison Liberation Series (Manila, Philippines). The Carl Mydans photographs were captured in the days following the camp’s liberation by allied forces. It was one of four camps liberated in the space of a month in January/February 1945.

Rest assured, I will return to this archive in time to source material and discuss more widely the politics of power partially described by the photographic collection. “Mexico Prison“, with over 150 images, certainly looks like interesting material.

Carl Mydans. Freed American and Filipino prisoners outside main entrance of Santo Tomas University which was used as a Japanese prison camp before Allied liberation forces entered the city. Manila, Luzon, Philippines. February 05, 1945

I would like to make clear that this is a hastily put together post and its main function is to draw attention to this fantastic whale-sized new archive – I might go as far to say our archive – I might even go as far to say its bigger than a whale. I do not condone personal whale ownership.

I would also like to clarify that while the LIFE Archive refers to the Santo Tomas Complex as a prison, it was in fact an internment camp – not that naming conventions matter to those who were subject to its walls and discipline. Still, we must always bear in mind the different types of sites of incarceration; what they purported to do; what, in truth, they did; from what context they arose and operated; and how they fit into our general understanding of humans detaining other humans.

Carl Mydans. Emaciated father feeding Army rations to his son after he and his family were freed from a Japanese prison camp following the Allied liberation of the city. Manila, Luzon, Philippines. February 05, 1945

Personally, I encountered a strange coincidence over this matter. Internment camps are low on my list of primary interest. I am not an expert on internment camps. But, only yesterday I received a fantastic email from a Berkeley art history undergraduate who is focusing on the work of Ansel Adams, Toyo Miyatake and Patrick Nagatani at Manzanar War Relocation Center, California. From the internet monolith that is Google to the academic interests of aspiring students, the histories, memories and powerful images of Second World War internment push themselves to the fore of thought.

Carl Mydans. Two emaciated American civilians, Lee Rogers (L) & John C. Todd, sit outside gym which had been used as a Japanese prison camp following their release by Allied forces liberating the city. Manila, Luzon, Philippines, February 05, 1945

It is conventional wisdom that World War II had two sides. Unfortunately, the military definitions of ‘ally’ and ‘enemy’ spilled into civic life with catastrophic consequences. The US internment of Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans has since been proved to be based not on national security but state-sanctioned discrimination. As testimonies and images attest, where stories are concerned, there are more than two sides.

Click here for the LIFE Archive on Google. Here is an obituary for Carl Mydans, the photographer at Santo Tomas. Try here and here for first-hand account of detention and to find audio and visual resources about Santo Tomas Internment Camp.

A modest welcome to all readers.

It is likely, if you are reading this in late 2008, you know me personally and you are acting upon a recent announcement of mine. Thank you for stopping by. I am taking the steps, finally, to submit to the world a long-gestating collection of ideas. If you do not know me personally, I am humbled by your browsing across my page. Please let me know how you came across the Prison Photography blog.

The forthcoming, ever-growing collection of posts will reflect my interests in art history & its social contexts, prison reform, the representation of prisoners in contemporary media, power & knowledge, and the experience of humanity within legal, illegal and disputed systems of incarceration.

The resultant trove of image and text relies upon the medium of photography to focus argument. Photography is the single criteria that defines the boundaries of my inquiry and it serves to unify the many stories and systems it has documented.

I am interested in all forms of art production within sites of incarceration. I have a keen interest in art therapy, its uses and measurements of success. I have strong political views about the nature of prison systems across the globe. I have a mild obsession with former prisons that have now entered the heritage industry reconstituted as museum or other cultural site. But these are not the prime concerns for this blog, and while some of my writing may point to these related ideas, and indeed even overlap, my primary interest is to look at photography as a visual resource, put it in a context of socio-political production and draw sensible conclusion.