You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

© Quico Garcia

In September, Ariel Rubin’s VICE article The Children of Kampiringisa was accompanied by Quico Garcia’s pictures, mostly portraits of the child prisoners.

The article describes a fetid facility, where child “offenders” (sometimes they’ve been dropped off by parents for poor behaviour) share cells with Kampala’s homeless children. The overcrowded facility breaks international law. Instead of rehabilitation, children endure malnutrition and diseases such as Malaria that – due to lack of medicines – they must “wait out.”

Upon entry into the rehabilitation prison, children are cooped in the “black house”—a barred room where they sleep on the floor, scramble for space and may to procure a filthy blanket. After 25 days they are moved to a dormitory with their own bed.

Garcia’s images for the piece do not show any of the squalid conditions. To the contrary his portraits are intimate and devoid of the trauma Rubin describes. One presumes, the Kampiringisa authorities would not allow photographs of the most desperate spaces and inmates.

VICE’s editorial decision to pair Rubin’s succinct and stark description of Kampiringisa with Garcia’s portraits leads to a dissonance between text and image and potentially misleads the reader/viewer.

Read the article here and view more of Quico Garcia‘s work from Kampiringisa here.

Lots of lists of photobooks cropping up for different reasons.

PHONAR

To close out the remarkable efforts of Jonathan Worth’s experimental open-sourced, web-based, free Photography and Narrative (#PHONAR) course offered through Coventry University, the #PHONAR course closed with a bevvy of recommended readings.

The following photographers, writers, teachers and journalists made picks:

Alec Soth; Andy Adams; Cory Doctorow; Daniel Meadows; David Campbell; Edmund Clark; Fred Ritchin; Geoff Dyer; Gilles Peress; Grant Scott; Harry Hardie; Jeff Brouws; Joel Meyerowitz; John Edwin Mason; Jonathan Shaw; Jonathan Worth; Ken Schles; Larissa Leclair; Ludwig Haskins; Matt Johnston; Michael Hallett; Miki Johnson; Mikko Takkunen; Nathalie Belayche; Peter Dench; Pete Brook; Sean O’Hagan; Simon Roberts; Stephen Mayes; Steve Pyke; Todd Hido

As a contributor, I picked out three titles. Predictably, each dealt with photography in sites of incarceration:

Too Much Time – Jane Evelyn Atwood

Chris Verene‘s Family was a later addition.

It was a privilege to be asked to guest lecture on this pioneering educational model. Thanks to Jonathan, Matt Johnston @mjohnstonmedia (Chief Engineer) and students for their encouragement and engagement.

WAYNE FORD

The #PHONAR list was spurred by Wayne Ford’s Photobooks and Narrative list.

JOHN EDWIN MASON

Following the #PHONAR list, contributor John Edwin Mason extended his selections. Mason’s Photobooks and Narrative: My (Slightly Flawed) Phonar List has an African and African American emphasis.

ALEC SOTH

Tonight, Soth put forward his Top 10+ Photobooks of 2010. As ever, Soth is thorough, thoughtful and generous in response.

JEFF LADD

Jeff at 5B4 has picked out his 15 choices for Best Books of 2010. The comments section is lively and I don’t think being to conceptual (as Jeff is accused of) is a problem, even if it were a fair allegation.

SEAN O’HAGAN

Sean at the Guardian has selected 2010’s best photography books that you should put in someones stocking.

NIALL MCDIARMID

Niall has put together his Photobooks and Magazines of the Year.

Recruit Gill and other recruits shout as they count down from 10 after being ordered to "clear the head", which means to exit the lavatory area. When the count reaches zero, everyone is expected to have put away their toiletries and be standing in line.

A couple of weeks ago, before Theo Stroomer headed off to Bolivia, we sat down for a beer.

After studying photojournalism at the University of Colorado, Stroomer went to work as a photographer for a newspaper in Vail, Colorado. He documented the Colorado Correctional Alternative Program (CCAP) in Summer 2008 as a personal project.

The CCAP, a boot camp style program, was the only program of its kind in Colorado and one of very few across the States. The three-month camp, which opened in 1991, offered physical & mental challenges, a GED program and substance-abuse treatment. About 90% of the offenders had drug or alcohol abuse problems

In March 2010, as part of Colorado State budget cuts, the boot camp was closed down. “There’s no political consequence in making a decision like that,” says Stroomer. The photographer observed change and believed it was a worthy program. Upon hearing news of the closure, Stroomer wrote, “I held a high opinion of the program, its staff, and its role in the lives of inmate participants after observing it over a three-month period in 2008. I am sorry to see it go.”

Staff use a technique called "corralling" to discipline Recruit Cardenas on Zero Day, the first day of the three-month program. Zero Day is the most intense day for new recruits. They are subjected to extreme physical and emotional stress, including supervised physical contact from staff members.

Recruits are rushed off the bus on Zero Day. To break new recruits mentally and physically, staff bark orders constantly, move them on and off the bus repeatedly, and batter them with physical exercises.

Admittedly, the boot camp program was more costly than simply warehousing prisoners. And costs were rising; from $78/day to $109/day per inmate in 2009 alone. Also unhelpful were the gradually increasing year-on-year recidivism rates among CCAP graduates. The Denver Post, in a rather damning summary, reports:

51% of the 155 inmates released from prison through boot camp in fiscal year 2007 have already returned to prison. The 51% recidivism rate of these nonviolent offenders was only 2% points better than the record of inmates convicted of crimes such as robbery and murder.

Another huge problem for CCAP – which only took non-violent first-time offenders – was the statewide rising proportion of inmates classified as “high security” compared to when CCAP opened in the early nineties. Indeed, it is telling that as the CCAP boot camp was being shuttered as another new maximum security prison was under construction in Canon City.

It should always be noted that the most inventive and progressive programs are more expensive than those which simply lock people up without rehabilitation efforts.

Ari Zavaras, Colorado Department of Corrections executive director, rolled out the stats to support the decision. I suspect negatively-spun statistics surface about any particular service whenever a state department is about to bin it. The closure of CCAP boot camp is forecast to save $1million in operating costs per year and relocate 33 full-time staff.

Recruit Greene log-rolls in "the pit", a gravel area that is used for group discipline and physical trials that are rites of passage in the program.

Recruits Shock, center, Davis-Gonzales, left, and Gill, right, smile during Prison Fellowship, a nationwide Christian prison ministry program that meets once a week during CCAP.

The squad bay, where recruits keep their toiletries and clothing in addition to sleeping at night. With good behavior from the entire platoon, recruits can earn amenities such as pillows.

BOOK

The Pain the Pride (Waterside Press, 2000) by Brian P. Block is an exclusive fly-on-the wall account of life inside the Colorado Correctional Alternative Program. It is available on Google Books.

STATS

The Denver Post reports on the unexpected, welcome and only half-explained trend of decreasing prison populations in Colorado (2009: 23,186 – 2010: 22,127).

Why the surprise? Shouldn’t one expect a drop in prison population if the state ceases to pursue (due to budgetary constraint) harsh, punitive legislation of boom years? After the postponement of insane policy, we should be looking how to reverse the damage and plummet the figures further. In 1981, Colorado had fewer than 3,000 prisoners. That’s the baseline to focus on.

Graduate Davis-Gonzales hugs his girlfriend, Povi Chidester, during a graduation ceremony at the conclusion of the three-month program. Inmates who complete the program attend the ceremony and are allowed one hour with family and friends. Their sentences are then sent to a judge for reconsideration. "I came here from a huge house with a bunch of coke, a bunch of money, a bunch of guns ... and now I have none of that. And I feel like more of a person now than I did then," said Davis-Gonzales.

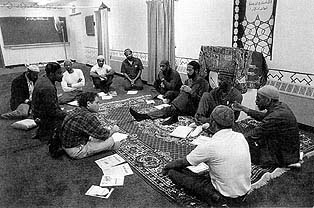

Verily, never will Allah change the condition of a people until they change it themselves with their own soul.

– Qur’an 13:11 or 8:53

Abdel Ameen, Halfway House. Richmond, Virginia. © Bryan Shih

Bryan Shih has produced an essay on prison reentry services for Muslims.

Shih says:

“Transitioning out of prison back into society is difficult for anyone, but the scarcity of Islamic centered re-entry resources often adds to the obstacles confronting prison converts to Islam. […] A lot of the people I photograph are from groups and communities that are on the margins, and that does something to their psychology.”

From a quick squint at Shih’s portfolio, Prison Converts to Islam, it is obvious he has traveled widely and photographed in San Quentin Prison, California as well as in Richmond, Virginia (above). Possibly in other states too.

I have very rarely spoken about Islam in US prisons, mainly because it is not a subject I know a lot about. But that is changing.

Recently, in discussion with New York based documentary photographer Jolie Stahl (about an altogether different project of hers from the mid-80s), Stahl took the opportunity to tell me about her photographs for the book Black Pilgrimage to Islam.

Stahl is married to the author, Robert Dannin, former editorial director of Magnum Photos, and professor of history at Suffolk University, Boston Massachusetts.

The book deals with all aspects of the Islamic experience in America and necessarily covers the increase in Islamic worship within US prisons among predominantly African American populations. Figures used for Dannin’s book indicate an increase in the numbers of self-identified Muslims in New York prison facilities between 1989 and 1992 (1989 in parentheses): Sullivan Prison, 84 (112); Green Haven Prison, 348 (286); Auburn Prison, 310 (234); Attica Prison, 388 (327); Wende Prison, 125 (74); and Eastern Prison, 175 (135).

Fortunately for us, chapter seven of Dannin’s book which is devoted to prison Islam is available online, as part of the digitised version of Making Muslim Space (Barbara Daly Metcalf (ed.), 1996, UC Press).

Dannin suggests that the body-focused discipline of Islam provides fortitude despite the stark, oppressive prison environment:

“If one tries to extend the Foucauldian idea of the prison as a simulacrum of the medieval monastery, there is a realization that something has changed, because this architecture conducive to introspection and Christian rebirth has increasingly become a place of mosques and communal prayers. The predictable monastic effect has been achieved, but somewhere its content has been subverted. […] Islam’s popularity in the prison system rests in part on the way in which qur’anically prescribed activities structure an alternative social space that enables the prisoner to reside, as it were, in another place within the same confining walls.

This same logic explains the rampant success of prison yoga initiatives. [1], [2], [3]

Door to Masjid Sankore at Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. © Jolie Stahl.

New York State was the progenitor for much of today’s prison-based Islamic worship. Dannin writes:

“Following the Attica riot, DOCS designated Green Haven, the scene of similarly explosive tensions, a “program facility,” where emphasis was placed on learning and rehabilitation as opposed to punishment. College courses, vocational training, substance-abuse programs, work release, and family-reunion visits resulted directly from a negotiation of inmate demands and the actions of newly appointed liberal administrators. Muslims were situated at the center of these activities …”

The community and equanimity fostered by Islam echoed the social justice priorities of the Black Panther movement. Swiftly, the Masjid Sankore at Green Haven “achieved its reputation as the most important center for Islamic da‘wa in America”. Dannin traces the understandable transition of locked down minorities from political revolutionaries to religious observers.

The Majlis ash-Shura, or high council, of Masjid Sankore at Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y., with author Bob Dannin (center left), 1988. © Jolie Stahl

Friday prayers at Masjid Sankore, Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. © Jolie Stahl.

Shu’aib Adbur Raheem, a former imam of Masjid Sankore, and his wife during a family reunion visit at Wende Correctional Facility, N.Y. © Jolie Stahl.

Damon Winter emailed me this week to let me know he’s been tinkering with his website. Since we spoke last [here and here] about his ‘Angola Prison Rodeo’ series, he’s revisited and re-edited.

http://www.damonwinter.com/ > STORIES2 > 5 > ANGOLA PRISON RODEO

The image above is new and one of Damon’s preferred images.

Also since then, Winter covered Haiti. It was his first work in a disaster area. This week, Winter’s Afghanistan i-Phone images hit the front page of the New York Times – Between Firefights, Jokes, Sweat and Tedium (James Dao, November 21, 2010)

On those i-Phone Hipstamatic App shots … three things.

1) David Guttenfelder did the same thing earlier this year with a Polaroid App.

2) The simple i-Phone angle is not a story. Judging by the cursory Lens Blog entry, I think James Estrin and Winter might have known this.

3) I’ll pass on the i-Phone photos. Mainly because these have got a stupid amount of attention; attention that should be going to Winter’s videography and incredible number of stories in his short time in Afghanistan.

Damon, I still love your portraits and I still dig your work!

ELSEWHERES

I’d also like to recommend my interview with Winter (for Too Much Chocolate) about his career trajectory.

As part of the ongoing OPEN-i project, Edmund Clark and I discussed Ed’s latest project Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out.

Ed’s nuanced work from on Guantanamo began with his documenting the domestic interiors of released British detainees. As Ed progressed he realised he needed to go to the US base on Cuba. The project deliberately jumps between these environments of “residence”, forcing the viewer to consider the personal as opposed media representations we otherwise rely on.

Ed’s work deliberately excludes portraits of detainees, partly because he feels those images are widespread but also due to a belief that audiences react to “images of bearded men” with unavoidable prejudice.

Ed also looks at the leisure spaces on Guantanamo that US military personnel inhabit during down time. The juxtapositions are poignant.

The photographs in the book Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out wrap around letters received by detainee Omar Deghayes during his time in Gitmo. Except they are not letters, they are copies, processed, redacted, re-processed, copied again. If he received a colour copy it was a rare treat. Some of the correspondence is so bizarre, Deghayes wondered if the were genuine or if they were props to the mind games played by his captors.

My family has been urging me for years to talk more quickly, and having heard myself here I get their point. The only excuse I have is that it was early in the morning here on the Pacific Coast when we sat down for the webinar.

Ed, on the other hand, talks wonderfully about the images and their situation in our shared GWOT visual landscape.

PHOTOGRAPHS AS IMPLEMENTS OF TORTURE

The book, Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out concludes with an essay by Dr. Julian Stallabrass. He describes a rather pernicious and Luddite use of photographs in psychological torture at Guantanamo:

Al-Qahtani was repeatedly shown photographs of scantily dressed women, along with images of 9/11, particularly pictures of children who had died that day, had the pictures taped to his body, and to ensure that he had paid them close attention, he was induced to answer questions about them.

This is a practice of interrogation of which I was not aware and is obviously troubling; a deliberate use of imagery to vex and agitate and an example of the power of photography as applied in an abusive context.

OPEN-i

Thanks to OPEN-i coordinator Paul Lowe for inviting me back once again. It’s an honour to speak with a photographer at the top of his game. OPEN-i is a global network hosting monthly live discussions on critical issues relevant to documentary photography and visual storytelling.

EDMUND CLARK

Edmund Clark is winner of the 2010 International Photography Awards (The Lucies), 2009 British Journal of Photography International Photography Award, and the 2008 Terry O’Neill/IPG Award for Contemporary British Photography for his book ‘Still Life Killing Time’. His work is in several collections including The National Portrait Gallery, London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

GITMO – OTHER READINGS

Prison Photography archive of posts referring to Guantanamo.

The Prison Photography Guantanamo: Directory of Photographic and Visual Resources (May 2009)

The Hell of Copper (L'Enfer du Cuivre). Series: The Hell of Copper. 1800x1200. January-November 2008. Accra, Ghana. © Nyaba Leon Ouedraogo

Burkina Faso-born Nyaba Leon Ouedraogo is one of the twelve shortlisted photographers for the Prix Pictet.

Burkina Faso-born Nyaba Leon Ouedraogo is one of the twelve shortlisted photographers for the Prix Pictet.

Ouedraogo’s ‘The Hell of Copper’ (L’Enfer du Cuivre) depicts the Aglobloshie Dump in Accra, Ghana. “From dawn to dusk, dozens of young Ghanians, from 10 to 25 years of age, exhaust themselves […] seven days a week. Their mission is to disassemble the old computers and burn certain plastic or rubber components to cull the precious copper, which will then be resold. Everything is done by hand or with iron bars, makeshift tools found among the refuse. They have neither masks nor gloves. There are not even any functioning toilets,” says Ouedraogo.

Ouedraogo quotes a 2008 Greenpeace report on toxic substances at the site:

– lead: in cathode tubes and monitors, harms the nervous, reproductive, and circulatory systems.

– mercury: in flat screens, harms the nervous system and the brain, especially in young children.

– cadmium: in computer batteries, dangerous for the kidneys and the bones.

– PVC: this plastic used to insulate electrical wires, when burned, gives off carcinogenic chemical substances that can cause respiratory, cardiovascular and dermatological problems.

Ouedraogo’s pictures are good, but I don’t think they are good enough. The story is vital but the images don’t live up to its importance (presuming the 10 images edit for the Prix Pictet are his best works.)

In truth, I don’t want to criticise the work of a photographer from Burkina Faso. When was the last time a photographer from Western, Eastern or Central Africa was shortlisted for a major photography prize? We should be celebrating the recognition. But Ouedraogo shouldn’t win; the project is not polished enough.

For the record, I don’t think big-guns like Taryn Simon or Ed Burtynsky should win either: they don’t need the exposure and their work is familiar, a bit dated and easy to digest.

I hope either Stéphane Couturier or Vera Lutter win.

INTRODUCING PIETER HUGO

Back to Aglobloshie. It’s a familiar subject to us photo-nerds, not least because Pieter Hugo’s Permanent Error about Aglobloshie did the rounds a few months back.

Abdulai Yahaya, Agbogbloshie Market, Accra, Ghana. 2010. @ Pieter Hugo

Hugo was very quick at turning his images round. They were distributed within months of his 2010 visit to Aglobloshie. Yet, it was Ouedraogo who went to the toxic site first; in 2008, a full two years before Hugo set up his camera.

Hugo has been the centre of debates on race and representation before, so it is with even more reluctance I draw the comparison to Ouedraogo. Hugo’s portfolio contains dozens of images and so it can boast a wider view of the poisoned micro-environment. This works in Hugo’s favour.

Both photographers emphasise the prevalence of child labour, the presence of grazing livestock and the use of found tools and noxious open fires to extract copper from the scraps. If you look at the statements by Ouedraogo and Hugo they contain virtually the same info.

Again, it is the story that is of primary importance, here.

The ultimate question then, is which portfolio is best likely to capture the attention and imagination of viewers enough for them to shift their worldview of politics, consumption and globally connected “growth”? (“Growth” is the theme of the Prix Pictet this year.)

Hugo’s work sells in galleries and it made for those gallery sales. It’s also a bleak look at the conspicuous consumerism. Ouedraogo’s work is uses photojournalist angles, some portraits and shots of the expanses of computer carcasses. Ouedraogo’s work is less cohesive. And for some reason I want to say it peels away.

I’m not really convinced by either, but I’d still err reluctantly to the foggy Hugo square.

The one thing Hugo’s work lacks is the sentiment (and hope?) of the picture below, with which Ouedraogo closes his portfolio.

The Hell of Copper (L'Enfer du Cuivre). Series: The Hell of Copper. 1800x1200. January-November 2008. Accra, Ghana. © Nyaba Leon Ouedraogo

The other eleven finalists for the Prix Pictet are Christian Als (Denmark); Edward Burtynsky (Canada); Stéphane Couturier (France); Mitch Epstein (US); Chris Jordan (US); Yeondoo Jung (Korea); Vera Lutter (Germany); Taryn Simon (US); Thomas Struth (Germany); Guy Tillim (South Africa); Michael Wolf (Germany). Biographies here.