You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Julia Schönstädt’ tag.

‘Claudia. 4 years’ © Julia Schönstädt

Statement of Being by Julia Schönstädt is a series of portraits and interviews with prisoners in Germany. According to Fotografia Magazine — which is running a series of six portraits currently — Schönstädt’s aim is “to dispel the stigma of the criminal and simply make the subject human.”

Schönstädt has worked with subjects of different age, gender, race and criminal prosecution. Some are sympathetic characters, others less so. Three women in their fifties are addicted to drugs; two see it as a problem, the other not. Harry is only 23 and doesn’t really seem to care if he goes back to prison or not. Then there’s the older guys who seem to be reforming themselves or aging out the game.

Most of the statements are insightful and honest. For example, when asked if prison helps people, Claudia (above) weighs her owns needs against those of others. There was positives for Claudia in the mere fact she was forced to come off drugs, but she accepts without that small mercy, prison is roundly a tough, tough place for most:

I know that I was in a personal situation where prison gave me space to breathe at first. If I would be torn out of my normal life now, and that can happen to anyone, that they get falsely accused, I would probably find that very traumatic. You are very helpless. You have very few possibilities to influence or shape things. You are completely dependent on the good will and concession of the officers. And part of it is also always luck, depending on what kind of people you will be put together with, and the groups that form. I think for a person who isn’t in an emergency situation as I was in, this is very dark.”

In every case, Schönstädt does a good job of revealing the interviewee. I suspect the excerpts are taken from longer conversations allowing Schönstädt to focus on the meat of the message. It’s a well-made project. But I am not without criticisms.

Schönstädt asks “Are You Ready To Listen?” but the query “Are You Ready To Look?” seems as appropriate.

Within in her presentation of both text and image, Schönstädt’s question seems to sideline the importance of the image . (This is not to say that we cannot conceive of a metaphor of “listening” to images, but for the purposes of my argument, I think it’s useful if think of listening as something related to written, read and spoken words.)

The question elevates the words of her subjects. Great. I’m all for portrait sitters having a platform to speak in their own voice. But I get the sense that here photography is used as filler and that the B&W portraits behave as illustration to the words, and as supplement. This is, of course, sad. We know photography can do many things and, I believe, it can be an activating agent in a project. In a purported photography project such as Statement of Being it absolutely must be activating.

But are we ready to look? When I do and inspect Schönstädt’s portraits I’m left wanting. They’re flat.

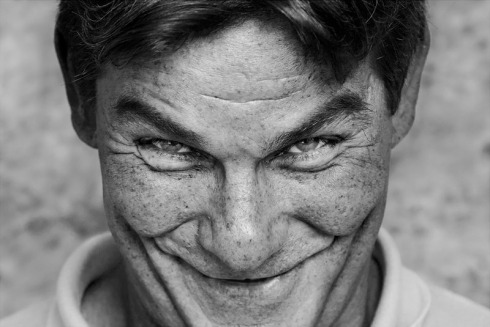

‘Volkert, 13 years’ © Julia Schönstädt

Now, we all know how difficult it is to make a good portrait, but these are so tightly cropped and made monochrome, I feel like I’m looking at a really earnest effort by an artist to depict someone, as opposed to looking at that someone. Schönstädt’s politics are aligned with mine and her use of multiple media is praiseworthy, but I don’t feel she has managed to do what great photography does, which is to get out the way of itself. Proximity doesn’t always mean intimacy.

I wonder if Schönstädt made the decision to get close so that she could remove evidence of the prison environment from her pictures? To give her subjects best chance at presenting as a person first and not as a criminal as default? I understand the urge but it’s not necessarily a solution. Nor is it necessarily a problem. For example, Robert Gumpert has used B&W imagery but drawn back and made the most of sterile pods in the San Francisco jail system to make compelling portraits. In short, I’d like to see more variation in Schönstädt’s portraiture.

‘Oliver, Life Sentence’ © Julia Schönstädt

I’m currently writing an essay “How To Photographs Prisoners Without Shaming Them.’ Most of the essay focuses on pairing photography with other media. In some bodies of prison portraiture it is either stated or obvious that the photographer collaborated with the subject over the composition and presentation. Given that Schönstädt’s portraits are identical in direction, I wonder if this was the case?

I am not saying Schönstädt doesn’t respect her subjects the opposite is clearly the case, but photography is more about the viewer than the practitioner and we must always be aware of existing stereotypes and prejudices when making photographs. The audiences’ reaction trumps the author’s intent. The audience’s reception is what defines a work ultimately.

Take the above image of Oliver as an example. Some might read his face as mischievous. Others, no doubt, will read it as menacing and devilish. I don’t think the appearance of a sinister looking male helps win sympathy. This is tragic for a project which is wholly sympathetic to the prison population.

Oliver speaks frankly and sensibly:

I became violent very early on. First there were money-related crimes starting at 7 or 8 years old. Violence came a bit later, but when I was 7 or 8 years old I stole and so on. Unfortunately, it wasn’t until I was 22 that I was held responsible for the first time.

It really struck me that something wasn’t right with me or with my story when a great deal of my family passed away – my grandfather, grandmother, and father [after being imprisoned]. I was married then and my wife divorced me. She stayed with me for 5 years but then she got to a point where she couldn’t take it anymore. And all that lead me to think something isn’t quite right here. Then I went to see a psychiatrist and got even more reasons to think about everything.

I had relatively little empathy for people, that’s just the way I grew up. I was raised in a violent environment. But that doesn’t mean that I was consciously punished by being beaten, more in a way you would also train a pitbull. […] I didn’t feel like that was something that wasn’t okay. I experienced my childhood as something really nice. Only through a person from the outside, I realised that it wasn’t all that normal, the way I grew up. And through realising that, I was able to reflect much better.

Oliver is in full grasp of his antisocial behaviour and has made steps in therapy to address it. He’s locked down for life but trying to improve himself. He is not devilish. How do I know this? Again because of Schönstädt’s keen efforts. Listen to Oliver speak in the video below and ask if the mood and personality of his still portrait tallies with that of the video portrait. Are we ready to look?