You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Juvenile Detention’ tag.

These images are the result of a collaboration between photographer Steve Davis and the girls of Remann Hall Juvenile Detention Center, Tacoma, Washington State in the US.

Davis was forced to think of the camera as a tool for different ends, essentially rehabilitative ends. For legal reasons and the protection of minors, Davis and his female students were not allowed to photograph each others faces. It became an exercise in performance as much as photography.

We see portraits of the girls with plaster masks, heads in their hands. The girls limbs outstretched made use of evasive gesture. The long exposures of pinhole photography resulted in conveniently blurred results.

PINHOLE PHOTOGRAPHY vs ROTE DOCUMENTARY MOTIFS

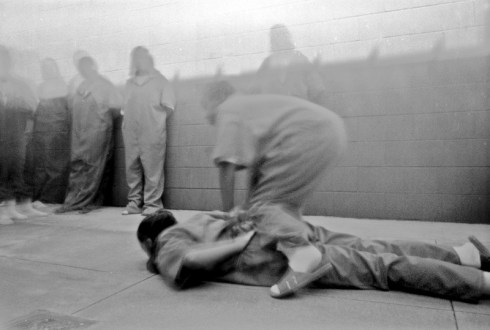

Photography in sites of incarceration often depicts amorphous, vanishing forms within stark cubes; it is usually black & white, and often from peep-hole or serving-hatch vantage points. When this vocabulary is used and repeated by photojournalists, visual fatigue follows fast.

Heterogeneous architecture doesn’t help the documentary photographer. Limited and repetitious visual cues make it tough to work in prisons. Images, shot through doors, by visitors only on cell-wings by special permission, are dislocating and sad indictments of systems that fail the majority of wards in their custody.

I celebrate all photography shining a light on the inequities of prison life. Having said that, very occasionally – only very occasionally, do I wish a “prison photographer” had expanded, waited or edited a prison photography project a little longer … but I do wish it.

Photojournalism & documentary photography have taken a battering from within and been asked some serious reflective questions. I don’t want to accuse photographers of complacency. To the contrary, my complaints are aimed at prison systems that so rarely allow the camera and photographer to engage with daily life of the institution.

Therefore, I stake two positions on the issue of motif/cliché. First, repeated clichés have developed in the practice of photography in prisons. Second, prison populations have had little or nothing to do with the creation, continuation or reading of these clichés.

As a general criticism, I would say photographers in prisons struggle to achieve original work. But, prisoner-photographers – whose experience differs vastly from pro-photographers, custodians and visitors – cannot be held to that same criticism.

WHEN THE PRISONER CONTROLS THE CAMERA

These images by the girls at Remann Hall are distinguished from the majority of prison documentary photography, because the inmate is holding the camera. When an inmate repeats a motif it is not a cliché.

These are images of all they’ve got; concrete floors, small recreation boxes, steel bars, plastic mattresses and chrome furniture … all the while lit brightly by fluorescent bulbs and slat windows. These aren’t images taken for art-careerism, journalism or state identification. These are documents of a rarefied moment when, for a while – in the lives of these girls – procedures of the County and State took back seat.

When a member from within a community represents the community, the representation is above certain criteria of criticism. A prison pinhole photography workshop has very different intentions than any media outlet. Cliche is not a problem here; it is a catalyst.

The simulation and reclamation of visual cliche (in this case the obfuscated hunched detainee) is doubly interesting. Why the frequent use of the foetal position? Why did the girls choose this vulnerable pose to represent themselves? Was it on advice? Was it mimicry? Was it part of a role they view for themselves? Why don’t they stand? Emotionally, what do they own?

As in evidence in some images, one hopes that some of these girls are friends. This selection of shots share a single predominant common denominator; the psychological brutality of cinder block spaces of confinement. Companionship seems like a small mercy in those types of space.

These photographs should knock you off your chair. I am in doleful astonishment. In the absence of faces, how powerful and essential are hands?

For now, consider how visual and institutional regimes square up.

Since the original publication of these images, they have been viewed tens of thousands of times. More than any other photographer – famous or not – these images by anonymous teenage girls have been by far the most popular ever featured on Prison Photography. That appetite shows that when prisons and struggle and creativity are presented in a meaningful way, images can be used as a segue into wider discussion of the underlying issues.

The Remann Hall project was done as a part of the education department program at the Museum of Glass in partnership with Pierce County Juvenile Court. This comment sums up the importance but also the fiscal fragility of these arts based initiatives:

“The Remann Hall project was an incredible project, which culminated in an outdoor installation at the museum and many of the participants coming to volunteer and participate in education programs at the museum after they were released. It was one of the many incredible programs I was lucky enough to be part of there. A book of poetry, artwork (and I think some of the photos in that link) was produced as well. The whole program was a great model for how arts organizations can do meaningful outreach in their communities. Unfortunately, the program was cut one year before the planned completion, due to budget concerns.”

[My bolding]

Robert Walsh contacted me recently to alert me his 2007 project at Delta College, Stockton, with instructor Kirstyn Russell. I asked Mr Walsh to explain the context of the series.

The story is not complicated. I have been a moderately serious photographer since the late 60s, when I got my first real job, working in the camera department of a large discount store. I have kept at it, off and on, for 40 years.

I got a job with the Department of Corrections in 1980 and worked at Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) for 24 years, retiring as a Lieutenant 4 years ago.

A couple of years after I retired I approached the Warden, who was about to retire himself, and asked for access to shoot a photo essay of the prison.

I promised that I would go to great lengths to ensure that there were no recognizable images of inmates (legal issues) or staff (personal/professional issues) and would give the Department veto authority over any photo with any possible security issues. It worked out, and they had no issues.

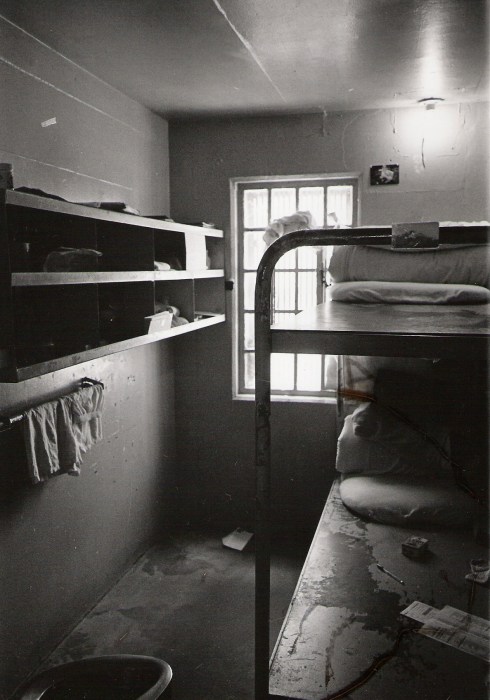

I shot about 200 frames of 35mm, 120 and large format B&W negative, and ended up with a collection of 20 prints which I put in the book Images of the Gladiator School, along with a few pages of text. The text is still evolving.

The photos were shot over two days in the fall of 2007. I was trying to convey the visual impact of the institution without showing any people, both for obvious legal reasons and as a technical/artistic “challenge” for lack of a better way of putting it.

Robert Walsh

Mr Walsh sent me through the series’ twenty images, from which I selected six.

Of the remaining fourteen, two of Mr Walsh’s photographs were of receding cell tiers, so they couldn’t be included by virtue of a pledge. Two more were of receding corridors, so I extended the pledge. Three other prints that stood out were exterior shots of the yards at DVI. They depicted similar spaces to those of elementary schools – I plan to return to these in a later post.

I choose a single photograph for its own reason and five others for shared reasons.

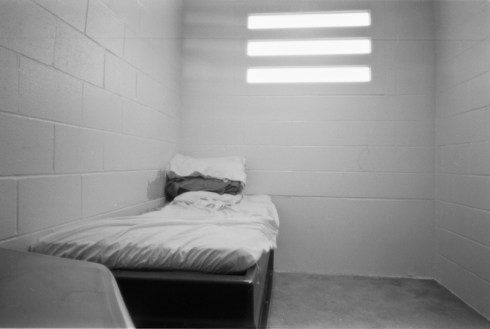

The image of the cell (above) is musty, scuffed and miserable as cell really get. Debris that lurks on the cold surfaces.

Mr Walsh actually provided two prints of the cell image; the other being less textured, darker and crisper. The other image also didn’t exhibit the same surface damage. The reproduction (above) was preferred because of its subtle mood of disintegration.

The remaining five were chosen because they express something of the action of the photographer. Away from the static buildings and fences, Mr Walsh has gone searching for anomalies amid the rigid penitentiary structures. The portrait of the cow is suitably awkward, the disturbed furrows of the field from which the owl flies are repeated in the pock-holes of the target range, repeated in the bullet-holes of the target-paper.

Robert Walsh

Robert Walsh

Palm trees. This is the West or Southwest, this is the land of middle distance road signs. This could be the work of John Divola‘s Correctional Officer Alter-Ego.

Robert Walsh

Robert Walsh

Robert Walsh

Mr Walsh challenged himself to “convey the visual impact of the institution” doing so with “no recognizable images of inmates or staff”. Bar two images, his compositions omit the activities of human life. Somehow, these five images specifically, give me the sense of human life recently fled or snuffed out entirely.

Whether Mr Walsh intended it, I find some of these images a little unnerving. The series is entitled Images of the Gladiator School based on DVI’s violent reputation between the 60s and early 80s. The project could as easily be called Ghosts of the Gladiator School.

Thanks to Robert Walsh for his time, words and images.