You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Abu Ghraib’ tag.

The American Psychological Association (APA) Council of Representatives, on Friday, voted today in Toronto to adopt a new policy barring psychologists from participating in national security interrogations. That means psychologists won’t be approving torture techniques or overseeing “enhanced interrogations.” That means psychologists can, and must, refuse to work in such capacities for the U.S. military and they will have full backing of their professional body in so doing.

Democracy Now! covered the decision, here and here.

My favourite comment came not from any of the APA members but from Peter Kinderman, the president-elect of the British Psychological Society who was representing the BPS at the APA meeting.

“I think it’s wonderful. I think it’s great. I think it’s well overdue. I was joking earlier that this represents American psychologists rejoining the 17th century and repudiating torture as a means of state power. […] The agreement is that American psychologists would respect agreed international definitions of the abuse of detainees and agreed international standards for judicial process. We shouldn’t be involved in abusing detainees, and we should remain within domestic and international law. That strikes me as commonsense, obvious. It’s what the public would expect. And about bloody time, too.”

TORTURE REVELATIONS

It was a double whammy this week. Everyone noticed the 6,000 page report into CIA torture. Many won’t know that today was the day that Justice Department attorneys presented the Obama administrations rationale for suppressing over 2,100 photos and videos of torture by American military personnel in Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Since 2009, the Obama administration has argued that releasing them would inflame anti-American sentiment abroad and place Americans at risk. Federal Judge Alvin Hellerstein of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York is not so easily convinced and wants the government to explain, photograph by photograph, how each might pose a threat to national security. The fight to release these photos dates to 2004, when the American Civil Liberties Union filed a Freedom of Information Act request.

David Levi Strauss has tracked these developments from the very beginning. Several chapters in his new book is Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow (Aperture, 2014) deal directly with the war over control of torture photos.

CONVERSATION

Strauss and I, for WIRED talked about state secrets, how the brain is wired, the political power of images and whether or not photos of Osama Bin Laden’s corpse actually exist.

WIRED: Why has the release of 2,000-plus remaining images and videos made by US military personnel in Abu Ghraib not been resolved?

Strauss: Because of the effectiveness of the images. They became the symbol of the change in US policy to include torture. Images are very powerful. That’s why the US government has become very afraid of the effects of these images worldwide.

The other amazing thing about the Abu Ghraib images was that they crossed the boundary between private and public. That is unusual. It changed things for photojournalism, for the military, certainly, and for the public at large. Prior to the release of the Abu Ghraib images, the military was handing out cameras to soldiers so that they could use photos to stay in touch with their families, and to be used operationally.

Read the full conversation: The War Over the US Government’s Unreleased Torture Pictures.

–

[All images for this Prison Photography post via Salon]

I recently visited the International Center for Photography (ICP). I was encouraged to see a photo from Abu Ghraib alongside one of Robert Capa’s Normandy landing photos and Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs from a liberated Nazi concentration camp. All were featured in the enjoyable and current A Short History of Photography exhibition, showcasing works acquired during the tenure of outgoing Director Willis “Buzz” Hartshorn.

Just as Capa and Bourke-White’s photographs are iconic of the WWII conflict, the Abu Ghraib digital photos are iconic and the images of America’s War On Iraq.

Both Capa and Bourke-White, in these instances, were photographers in the thick of it, in the moment, to deliver important news of the day to corners of the globe. Of course, the rise of citizen journalism has put pay to the idea that roving career photographers are now the first to a scene of international significance.

Without doubt the Abu Ghraib images – given their historical and cultural significance and dissemination – are rightfully in the ICP collection. That is not the issue; my questions were about the label:

Unidentified Photographer: [Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, nicknamed Gilligan by U.S. soldiers, made to stand on a box for about an hour and told that he would be electrocuted if he fell, Abu Ghraib prison, Iraq], November 4, 2003. INKJET PRINT. Museum Purchase, 2003 (113.2005)

Museum purchase? Who would be a recipient of payment for the image? I suspected it might be a case of language and not action. Ever interested by provenance and the accession of items into museum collections, I emailed ICP the following questions:

– Is “Museum Purchase” just a standard note you attach to works or did ICP actually hand over money to someone or some body for the image?

– Did ICP print it off the internet?

– When deciding to acquire it into the collection, what decisions were made about the file, the printing, the paper, the ink?

Kindly, Brian Wallis, the Deputy Director/Chief Curator at ICP responded:

The Abu Ghraib photograph now included in the “A Short History of Photography” was originally printed for the ICP exhibition “Inconvenient Evidence: Iraqi Prison Photographs from Abu Ghraib” (Sept. 17-Nov. 28, 2004).

At the time, only about twenty JPEGs were available, either on the Internet or from files supplied by the New Yorker.* We printed all images then available for the exhibition. They were printed on a standard Epson office printer, on standard 8½” x 11″. office paper, and pinned directly to the wall in the exhibition, in part to emphasize the ephemerality and informational nature of the pictures.

They were printed directly from the web with the understanding that these photographs, taken by U.S. government personnel, were in the public domain. We did not pay for them. The credit line in the current exhibition describes them as “museum purchase” in part because there is no other official museum description for how we obtained them; one could say we purchased the supplies used to print them.

So, no money exchanged hands. A relief of sorts. What one would expect.

I suppose ultimately, I have to give ICP some recognition for its 2004 reflex response to the pressing visual culture issue of the day; for presenting a set of images that for all intents and purposes falls outside of the normal acquisition avenues of major institutions.

ICP’s home-brew solution to show the Abu Ghraib, non-rarefied, non-editioned and thoroughly contemporary set of images is against the grain of many other museums chasing gate receipts through edutainment.

Left: Photo of allied forces landing on Normandy beaches, by Robert Capa; right: Photo of torture at Abu Ghraib, by unknown photographer.

– – – – – – – –

*Seymour Hirsch, who wrote Torture at Abu Ghraib (May, 2004) for the New Yorker, also provide the text for ICP’s Inconvenient Evidence exhibition – the catalogue for which you can download as a PDF

– – – – – – – –

All images: Pete Brook and taken without permission.

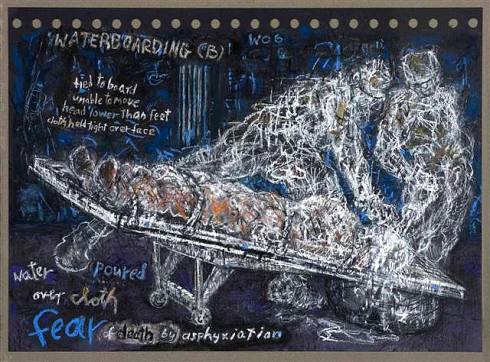

Black Book of Aggressors I 17 THE HEAVY CABLE WIRE. Selma Waldman. Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

“The perpetration of violence takes away an individual’s humanity, abuser and victim are locked in one energy field, that is like sex, they join together with energy, but in [Waldman’s] energy field, they are killing and being killed.”

– Susan Noyes Platt (Source)

Selma Waldman (1932-2008) is one of the great American artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. Unfortunately for the American public, her work has been more widely exhibited in other parts of the world, particularly in Germany.

Just as I insisted when I wrote about Daniel Heyman’s Portraits of Iraqis, it’s often worthwhile to look non-photographic work. As with Heyman’s work, I was introduced to Waldman’s work through Susan Noyes Platt’s vital book Art and Politics Now.

During Waldman’s lifetime, Noyes Platt was a vocal cheerleader for her work. Following Waldman’s death, Noyes Platt reconstructed her studio in a Seattle gallery space.

One of her final projects, Waldman’s Black Book of Aggressors explores her life long exploration of personal abuse between humans set in the milieu of widespread terror. The work is clearly to be understood within the context of the Abu Ghraib images but Waldman’s use of pastel extends the horror and successfully creates something significantly different and more nuanced. (I point people towards Antonin Kratochvil’s Homage to Abu Ghraib as an example of how photography can fail in it’s response to atrocity.)

Waldman conjures violent sexual depravity that represents any torture scenario, but because of global events, we know she is passing commentary on the U.S. military. It is difficult work … even for the art establishment.

Of Black Book of Aggressors Noyes Platt says:

“No museum will touch her potent work that exposes the intersection of sex, war, and torture. Her most recent series is on black paper with chalk lines in blue, red, yellow. It is a tangle of passionate fury that ensnarls interrogators and victims in a process that has no moral parameters. She declares in the brochure “War is the Crime, Naked/Aggression is the work”

In as much as the artistic process can mimic the mayhem of torture, I think Waldman succeeds and viewers are mired in what she described as “the pornography of power”.

I don’t repeat the phrase “the pornography of power” lightly. Particularly in photography circles there have been recent re-examinations of what it actually means to describe an image as pornographic. See David Campbell’s excellent essay The Problem with Regarding Photography of Suffering as ‘Pornographic’ as an introduction to the topic.

But with Waldman’s work we’re dealing with pastels and not photos.

One of the challenges to the lazy use of the term ‘pornography’ is that it is often applied specifically to photography, and as such infers something innately violating about photography. Susan Sontag is the often quoted name when people want to discuss photography and violation.

To determine what Waldman achieved with her work and also what we experience as viewers, it is worth considering Campbell’s summary of the term ‘pornographic’:

As a signifier of responses to bodily suffering, ‘pornography’ has come to mean the violation of dignity, cultural degradation, taking things out of context, exploitation, objectification, putting misery and horror on display, the encouragement of voyeurism, the construction of desire, unacceptable sexuality, moral and political perversion, and a fair number more.

Most of these are present in Waldman’s work and yet because she has created a scene and expressed it in pastel, the artworks are essentially invitations to join the artist in protest.

We know that Waldman was not present as the torture and perversions occurred. With photography, on the other hand, we cannot escape the fact that along with the camera there is (usually) the camera operator.

Photography “places us” in the violent space of the original act, whereas painting often puts us in the artist’s imagination. When we engage with a photograph and substitute the camera operator with ourselves, we are repulsed. Often we’ll look away and often we ask, how could they take such a photograph?

Painted art is rarely in the position to be so closely associated with the violence of the act it depicts. When we note Waldman’s violent brushstrokes we celebrate them as conceptually consistent. When we note that a button on a camera was pushed, we may think, “Why didn’t the photographer intervene.” The answers are many and the interventions not as easy as we might hope.

Under the Websters entry for ‘pornography’ the third of three definitions reads:

The depiction of acts in a sensational manner so as to arouse a quick intense emotional reaction, i.e. the pornography of violence.

So, the issue is not that depictions of violence shouldn’t be referred to as pornographic, the issue is that too often images – and particularly photographs – of violence are referred to wrongly as pornographic.

Perhaps the most licentious element of pornographic photos is that of voyeurism. As much as people who consider photography like to discuss the contradictions and layers of meaning within photography, it seems to me, in this comparative case at least, that Waldman’s simpler direct pastel-works are a more substantive experience for the audience. They cannot be dismissed as cheap voyeurism.

Think about it. If we are shown photographs of violence then we must automatically denounce the violence. Simultaneously, the presumption is we are also repulsed. Yes, we can be made to look away, but does that mean we never look back?

A photograph holds within it a never-ending capacity for voyeurism. It is a literal depiction and (I might get in trouble for saying this) it is closer to representational truth than any painting is.

Waldman’s pastels truly are the pornography of power; it is an appropriate phrase for her work. It’s a pornography we can look at and possibly learn from. Waldman depicts the perversions of imperial power without implicating our perversions. Her artwork severs the view of the aggressor from our own view.

In Black Book of Aggressors, you don’t find the voyeuristic tension that exists in photography. It’s powerful, relevant and persistent art.

Black Book of Aggressors, NAKED/AGGRESSION. Selma Waldman. Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

Black Book of Aggressors I. CHAINS OF COMMAND. Selma Waldman Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

Black Book of Aggressors IV 35 WATERBOARDING. Selma Waldman Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

Black Book of aggresors IV WATERBOARDING. Selma Waldman Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

Selma Waldman. Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

Black Book of Aggressors IV 39 WATERBOARDING PROFESSIONAL. Selma Waldman. Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

GITMO JACK, NAKED AGGRESSION. Selma Waldman. Black Book of Aggressors 2005 – 2007, charcoal, pastel, on black paper, 8 1/2 x 11″

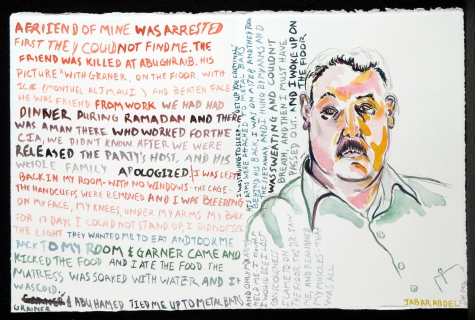

“The friend was killed at Abu Ghraib. His picture with Graner, on the floor with ice and beaten face. He was friend from work.”

– Jabar Abdel, former Abu Ghraib detainee, quoted in A Friend of Mine Was Arrested (below), by Daniel Heyman

Anyone that has made analysis of the photographs of Abu Ghraib should also be aware of Daniel Heyman‘s paintings Portraits of Iraqis.

Heyman made the watercolours and sketches while sitting in on interviews between former Abu Ghraib detainees and Susan Burke, a human rights lawyer with Burke O’Neil LLC, Philadelphia. Burke was looking to bring in artists and writers to tell the stories of her clients in different ways and to reach a wider audience. (Simultaneously, photographer Chris Bartlett was also working on portraits for his Detainee Project.)

Heyman had previously used facsimiles of the Abu Ghraib pictures in his mixed-media and woodblock artworks, but had become discouraged by the laziness of the appropriation:

“The potency of those images really diminished. All sorts of artists had started to use these images, and the more they were used, the more they indicated Abu Ghraib without providing any understanding of Abu Ghraib. They became a kind of code for anger about so many things to do with the war. You flash on the famous picture of the man on the box, and people become numb to that image. And you re-humiliate that man. You re-victimize that person.”

I recently saw three of Heyman’s works in a gallery; they are the perfect foil to those infamous images of Abu Ghraib. In December 2008, upon reflection of Standard Operating Procedure, Errol Morris’ film that gave the US soldiers a voice against the military brass, I suggested, “what the global community needs now is an equally comprehensive documentary project bringing together the testimonies of all those held and tortured at Abu Ghraib.”

There have been articles written, lawsuits brought, oral testimonies made – but Heyman’s work stands out as a particularly successful enterprise. Heyman makes the paintings and records the words in real time as the interview goes on. A slightly grueling process about a horrifically grueling topic. Heyman brings us very close to these victims of torture; they are no longer the abstractions we’ve known through the Abu Ghraib files, but individuals with the knowledge and details of fact that should shake our conscience.

In consideration of the broad range of artists’ responses (from good to bad) to the Abu Ghraib images of torture, for me, Daniel Heyman’s paintings carry an impact far beyond that within the capabilities of most photography.

Read Heyman’s interview with Foreign Policy in Focus.

View Heyman’s website.

SmithMag has an easy-to-navigate gallery.

Joan Fontcuberta describes his work as “anti-authoritarian.” He is a self-taught artist and former journalist who has adopted the tricks and issues of media manipulation/propaganda into his work.

Fontcuberta’s Googlegrams are “large, colorful photo-mosaics that construct a metaphor for the internet-era’s liaisons between mass media and our collective consciousness. Using Google to blindly cull images from the internet by controlling only the search engine criteria, Fontcuberta then assembles them by another computer program into a larger photomosaic image of Fontcuberta’s choosing.” (Source)

Fontcuberta’s an iconoclast, a philosopher and doesn’t trust the image. He encourages people to distrust, but ultimately recognises that people must believe: “people need information.” (Which may relate to the necessary reinsertion into – and commitment to – the image Joerg’s calling for.)

It’s all about healthy skepticism and filtering. He’s the furthest thing from a pessimist; he teaches photographic history and adores the medium. But he is not a sap.

Fontcuberta’s work deliberately fictionalises and questions. Jim Casper’s well-metred audio interview and VICE‘s interview flesh out his approach and motives.

What I admire about Fontcuberta is that having abandoned the urge to fight against the crimes of photoshop, advertising and image politics, he plays them at their own game. His ideas are uninhibited; it doesn’t matter if the lost Japanese soldiers of WWII in the Philippines jungle that he went in search of exist or not. Fontcuberta puts the exploration of an idea before the pressure to produce an end product. “The look of my work is not important,” he says.

Fontcuberta is playful and really jolly. I’d love to see him take on a cryptozoology expedition!

BIO

Joan Fontcuberta was born in 1955 in Barcelona, where he continues to live and work. He has exhibited extensively at museums and galleries in the U.S., Europe, and Japan, and has been associated with Zabriskie Gallery since 1981. His work is in numerous institutions, including the New York Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago. He contributes regularly to scholarly journals and has published many books, including Fauna, Sputnik and Miracles and Co.

FOR A HANDLE ON THE US MILITARY’S COMPLICITY IN WIDESPREAD TORTURE IN SAMARRA, IRAQ, WATCH THIS.

FRAGO 242

FRAGO 242 is the US military’s abbreviation of a “fragmentary order” given to US military operatives.

When US military became aware of Iraqi torture of other Iraqis, to quote The Guardian‘s David Leigh, “FRAGO 242 meant that no further investigation was necessary.” When in the custody of Iraqi security forces, detainees were subjected to horrendous abuse. The US turned a blind-eye. The information about this is brilliantly presented in this seven minute video.

Iraqi commandos securing the area after a car chase resulted in the arrest of foreign terrorists. Gilles Peress/Magnum, for The New York Times. (Cropped from original)

Included in the seven minute video are Gilles Peress’ images from a New York Times assignment in 2005. (You can find 23 of Peress’ image from the assignment by searching “Peress Iraq Counterterrorism Commandos” on the Magnum website.)

The writer for that assignment was Peter Maass. He was reporting on the elite Iraq Ministry of Interior Commando Force, known as the Wolf Brigade. For the assignment, Maass shadowed Col. James Steele who he describes as “Petraeus’ man.”

At the invite of Steele, Maas visited a Samarra interrogation center. In this same video, Maass describes the sights and sounds of torture from within. During the interview incredibly loud screams of pain could be heard throughout the building. According to Maass, Steele left the room, the screams fell silent, Steele returned and Maass continued his interview with a Saudi prisoner.

Steele has not yet commented on Maass’ account of that day in Samarra.

General Abul Waleed, Head of Command for the Wolf Brigade, and Col. James Steele, Samarra, Iraq. Gilles Peress/Magnum, for The New York Times.

WHAT JOHN MOORE DIDN’T PHOTOGRAPH

All of this is a very interesting counterpoint to John Moore’s In American Custody.

Moore’s compilation of images from embedded positions at Abu Ghraib and Camp Cropper (2003-2007) have been roundly celebrated since their publication on the 22nd Oct. I don’t see it. The collection is a politically safe edit of images from a war we are technically out of; they are the product of US military deceit. Moore was their pawn.

Moore’s images are benign in comparison to the descriptions set forth by Maass, the Wikileaks files and the thousands of Iraqis whose stories of torture have fallen on deaf ears for the past six plus years.

For a long time, in the early days of the war on Iraq, Abu Ghraib was a primary target for insurgents. Even before the photographs of torture were leaked, Abu Ghraib was mortared almost daily. Abu Ghraib held thousands of falsely accused men, the majority of whom were later released without charge, ceremony or apology.

Monica Haller‘s new book Riley and His Story is a collection of thoughts, diary entries and digital photographs from his tour of Iraq. For a period, Riley was a nurse in Abu Ghraib and the images from the medical tent are novel, uncensored, bloody.

Riley’s photographs from the hospital sits between snapshots from military vehicles, marines sat in paddling pools, goofy group shots, Al Franken (?) and decaying out-of-use planes.

This is the aesthetic we all know exists and we occasionally glimpse when there is interest, lawsuit or cultural re-use of military personnel snapshots in the media.

There must be millions of digital photos by American marines. Haller’s book is simultaneously a cleverly assembled piece of the wider dissemination of such imagery and an affirmation to the unexpected familiarity of such imagery.

A 21st century war is not a war without vernacular conflict photography.

Just as soldiers of WWI sent home words thus defining modern war poetry, so the soldiers of today bring home pixels and jpegs and define modern war imagery.

The singular prose, simile and letter-writings that painted a mind’s picture have been replaced by the multiple functionaries and fingers of digital observation.

As were the Abu Ghraib torture photographs, why shouldn’t we expect the next most iconic images of this century to be amateur snapshots? And why shouldn’t we be prepared for an equivalent violence in said iconic imagery?

It is curious that discussions about the lamentable loss of unembedded journalism have not always been balanced by discussion on the tumorous growth of ‘soldier-journalism’ (a term unsuitable, but an understandable extrapolation from the term ‘citizen-journalism’).

Whether you like it or not, the Canon PowerShot and its hand-held competitors own the future of war coverage.

Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon buffered the cruelty of war, but there are few artists now. (We are grateful to Haller for being such a thoughtful manager of Riley’s output.) Nothing is softened or made poetic/metaphorical. Laid bare. Perhaps, both the best and worst of scenarios we should expect is military censorship?

Monica Haller’s book is important not because it is Abu Ghraib and not because the images are snapshots made by American military personnel, but because it is a portent of an aesthetic already upon us. And we are in denial.

From here on in photography is ugly.

I found this project through Alec Soth on the Little Brown Mushrooms blog, via LensCulture.

A video interview with Haller is permanently available at LBM vimeo.

A sizeable preview pdf (over 100 pages) of Riley and His Story is available here.

Riley and His Story has a website. You can find out more about Monica Haller here, here and here.