You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Afghanistan’ tag.

A boy from Afghanistan tries to keep warm after a cold and wet crossing from Turkey. Cases of hypothermia are on the increase as the weather deteriorates across the eastern Mediterranean.

In an image saturated world it’s difficult to define and measure the effects of photographs. We know advertising works, but those are images intended to sell us stuff. What if the purpose of a photograph is to “sell” us of a moral or political point? What if a photograph wants us to shift our emotional and practical response to far away events?

Giles Duley’s work Lesvos: Crossing To Safety made in Greece last October are intended, firstly, to bear witness and, secondly, to provoke action to help the hundreds of thousands of migrants. That’s why he didn’t simply make images and send them to the wires, but he courted the support of the United Nations so that he might extend the distribution of his images — and the refugees’ stories — far into global, humanitarian dialogue channels. (This UN-produced feature on Duley’s career and motivations is very thorough.)

Not content with only traditional distribution channels, Duley looked for alternative ways of launching his images into an unorthodox space; a Massive Attack gig.

“The scenes were overwhelming,” Duley said to the UNHCR. “In all the time I’ve worked, I’ve never seen such emotion and humanity laid so bare as I witnessed on the beaches of Lesvos. One of the first emails I sent was to the guys in Massive Attack. Seeing such events, I felt so powerless, I needed to do something. At that stage I had no idea how the collaboration would work, but I knew the band would want to act.”

Stills of Giles Duley’s photos on screen behind the stage of Massive Attack. Courtesy: Massive Attack.

A founding element of the era-defining Trip Hop genre, Massive Attack are known for taking forthright stances on political and governmental behaviours. Saturday Come Slow, their collaboration with released British Guantanamo detainees, Broomberg & Chanarin and Damon Albarn was poignant, crafted and clever, I thought.

Furthermore, as Alexis Petridis wrote for the Guardian, “Massive Attack have worked with the Stop the War coalition and visited refugee camps in Lebanon, while in 2011, Del Naja and Radiohead’s Thom Yorke threw a party for Occupy protesters who had taken over a UBS bank building in London.”

It’s not surprise Massive Attack are lending their support to Duley and shocking their euphoric crowds with thumping reality. Duley’s images loop throughout the gig, but they get their biggest showing at the close of the show, when the music ends and the band leaves the stage. For minutes — in silence — the crowd is shown a mammoth slideshow of Syrians and other migrants landing in boats, hungry, tired and terrified. A far cry from the revelry of a gig. But people stayed. This Channel 4News segment is well worth the watch:

History has taught us that photos can certainly alter the mood of entire populations. Practice has also taught us that earnest, targeted messaging can help photos land. I hope more artists can lend a hand to serve the messages of humanitarian photographers. Usually, professionals commission images to be made to meet their own messaging needs so it’s great to see artists, citizens and successful public figures provide space within their platforms to amplify photographer’s voice.

Included here are Giles Duley’s images from Lesvos, Greece, made in October 2015.

An overcrowded boat carrying Syrian refugees heads to shore. One Syrian man had fallen from the boat into cold water. He was later rescued by volunteer Spanish lifeguards. Despite the approach of winter and worsening weather, refugees are continuing to arrive on the island at a rate of more than 3,200 per day. As of mid-November, at least 64 people have drowned this year in 11 shipwrecks off Lesvos.

Boat after boat lands on the coast of Lesvos between Eftalou and Skala Sykaminia. Over 45 per cent of the 836,088 refugees and migrants who have arrived in Europe so far in 2015 have landed on this Greek island, which is separated from Turkey by a 10-kilometre channel.

An Afghan mother holds her child moments after landing on the beach near Skala Sykaminia. UNHCR and its partners work to prevent family separations and create safe areas for women and children who are particularly vulnerable.

An Afghan family of several generations disembark from an overcrowded boat. Almost 40 per cent of refugees currently arriving on Lesvos are from Afghanistan.

–

UNHCR is working around the clock with other agencies and aid groups, stockpiling and distributing winter aid items to keep vulnerable people, both in camps and urban settings, protected and warm. Donate money to the UNCHR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees) here.

• The distribution of winter survival kits including high thermal blankets, sleeping bags, winter clothes, heating stoves, and gas supplies.

• The provision of emergency shelters including family tents, refugee housing units and emergency reception facilities.

• Improvement of reception and transit centers and preparing and supporting families for winter conditions.

You can help make a difference. Donate money to the UNCHR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees) here.

–

A relieved Afghan family, clearly still suffering from the trauma of a rough sea crossing at the hands of people smugglers, disembarks from a flimsy vessel onto a Lesvos beach.

An Afghan mother hugs her child and cries with relief after arriving on Lesvos.

Survivors struggle ashore after their boat has capsized. In the background a Spanish lifeguard, one of the many volunteers working on the beach, swims out to help other survivors.

A Syrian father, his two children now safely wrapped in thermal blankets, looks to the heavens in thanks after landing safely on the beach.

A young Afghan boy with his aunt. His mother is receiving emergency medical treatment after she collapsed upon landing. Since August UNHCR, in close cooperation with the Greek authorities and other humanitarian actors, has considerably stepped up its activities to respond to the increasing needs. This is even more imperative with the onset of winter.

Volunteers prepare to wrap a young girl in an emergency blanket to protect her from the cold wind.

–

Follow UNHCR on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Donate money to the UNCHR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees) here.

Read ‘War Survivor Focuses Lens on Refugees‘ about Duley’s work in Greece. Reacquaint yourself with the ‘Lesvos: Crossing to Safety‘ feature. Read a review ‘How Many Stories Can You Tell In One Second?‘ of Duley’s new book One Second of Light.

Connect with Giles Duley on Facebook, Twitter, Linked In and EW Agency.

NO BARS, NO GUARDS, NO LOCKS

Tattered lace curtains, taped family photos, patterned carpets, plastic flowers and snappy fabrics. Gabriela Maj’s portraits from the series Almond Garden have all the chirpy, easy-to-patronize details of portraiture from a former Soviet controlled region. Lost you already? Think of Sergey Poteryaev’s portraits, Rafal Milach’s Winners in Belarus, Olya Ivanova’s portraits of young girls in rural Russia or anything by Sasha Rudensky. More directly consider the backdrops photographed by Lucia Ganieva.

(As much as I hate top-loading an article with links to a host of other photographers, I must because before we can understand how special and different Maj’s work is, we must appreciate the en vogue photo practices from which it emerges and above which it must rise.)

For the moderately trained eye, Maj’s work is obviously anchored within a super-region that still carries the visual culture of its immediate past. No matter how hard former Soviet countries try, nor how quick they build, photographers still seem to be able to isolate the details that’ll whiplash people back in time. The problem I outline here is twice as tricky because we, in the west, think that all changes in the former USSR since the end of the Cold War must at least be headed in the right direction.

The framework I am trying to set up here, basically, is that in which Soviets — and all those formerly-ruled by them — are ‘Othered’ and misunderstood by most viewers looking at photographs made in the region. I offer a word of caution before you step into Maj’s portraits. The stories burdened by the women in Maj’s Almond Garden are devastating and the worst thing we can do with Maj’s work is to lump it in with all that work of the knackered Russian empire.

Over the course of four years (2010 – 2014), Polish Canadian photographer Gabriela Maj travelled throughout Afghanistan to collect portraits and stories from inside the country’s women’s prisons. She visited with many of her subjects on multiple occasions.

Maj actually believes that being of Polish origin helped her to gain relatively unhampered access. Poland and Afghanistan shared a history of Soviet oppression.

It also helped being a woman. In fact, her mode and ability of movement revealed the so very twisted logic of a prison system that brutalised women.

“As a solitary female photographer, accompanied only by an Afghan interpreter, I was frequently left alone in the prisons once our guard escort tired of monitoring me. My sense was that unaccompanied by any security, a woman, albeit a foreign one, was not considered a threat,” she writes in an essay featured in the book. “Being overlooked in this way became a strategy that ultimately exposed the context within which I was working, one where women’s narratives were considered irrelevant to the power dynamics that ran the country.”

Maj went the extra mile and then some. The least we can do it get there with her. The majority of the prisoners Maj documented were incarcerated for what are known in Afghanistan as “moral crimes,” a term used to condemn those who’ve had sex outside of marriage, or run away from any number of abuses — forced marriages, being sold into prostitution, domestic slavery, physical violence generally conducted by their husbands, and rape and involuntary pregnancy.

Indeed, the portraits are powerful but it is the relentless injustice of the testimonies of the women that delivers the power and absolute necessity of Almond Garden. Maj has changed the names of the women to protect their privacy. She goes a step further and moves the stories to the back of the book.

“Separating the portraits from the stories has allowed for a record of the experiences of this group without any one woman being defined by the crime she was accused of,” explains the press release.

Each entry leads with the offense that the woman is accused with, her age and the length of her sentence.

I haven’t been so effected by a project pairing portraits of women with their transcribed words since, strange as it might be to offer, Malcolm Venville’s The Women of Casa X, which features portraits of aging sex-workers in Mexico. But, then again, perhaps not so strange? Both the women in Melville’s work and the prisoners in Maj’s work have been categorized, judged, ostracized and maligned by dominant patriarchal culture. In both cases, if the photographer hadn’t shown up, these stories would be buried (which is the culture’s intent, right?)

“Often times rejected by their families, these women’s situations can become grave after they are released,” says the Almond Garden‘s blurb. “Without the protection of their relatives that spurned them, they are often in very real danger of being killed or tortured unless they are able to seek refuge in a women’s shelter.”

It is bittersweet to think of these tortured moments in prison might be, for some women, where emotional and physical trauma exists least. That said, there is no psychological treatment or therapy available within the prisons Maj visited.

The title of the book Almond Garden is a play and is incongruous. It is the English translation of Badam Bagh, the name of Afghanistan’s most notorious penitentiary for women, located on the outskirts of Kabul.

Almond Garden publishers, Daylight Books, say that Maj’s project is the “largest record documenting the experiences of incarcerated women in Afghanistan produced to date.”

It’s stunning. It works in waves as all good photography should. I’ve been drawing important lessons from Almond Garden each time I’ve returned to it. Aesthetically, it’s as good as Michal Chelbin’s Swans and Sailboats, portraits from Ukraine and Russia. Ethically, I think it surpasses it as Chelbin is evasive about the details of her access.

BOOK TOUR, NOW!

Maj is currently on book tour.

Los Angeles tonight! If you’re in San Francisco, hit up one of her two events next week. On May 5th, at Modern Times Bookstore, or on May 6th at The Women’s Building.

BUY THE BOOK

Here, for $45.00.

DATES ON THE ALMOND GARDEN BOOK TOUR

May 1st, Exhibition and book signing with Daylight Books at the Leica Gallery in West Hollywood, CA.

May 5th, Presentation and book signing at Modern Times Bookstore in San Francisco, CA.

May 6th, Presentation and book signing at the Women’s Building,7:30-9:00, San Francisco, CA.

May 9th, Presentation and book signing at Apostrophe Books, 5:00-7:00pm, Long Beach, CA.

May 22nd, Presentation and book signing hosted by the Vermont Professional Photographers Association and the Peace and Justice Center, 6;00-8:00, Burlington, VT.

July 31st, Exhibition opening and book signing at Daylight Project Space , Hillsborough, NC.

August 8th, Book signing at Author’s Night 2015, East Hampton, NY.

Edmund Clark is cheeky, thoughtful and a bit subversive in his critique of institutional power. During his 10 days embedded at Bagram Airbase in October 2013, he realised most people there don’t ever get outside its confines.

But Bagram has nice paintings of murals to provide an idealised Afghanistan.

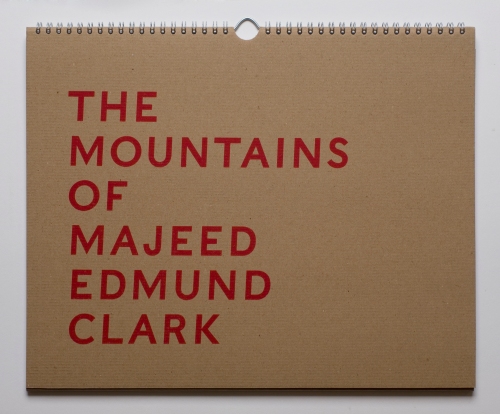

My latest for WIRED, The 40,000 People on Bagram Air Base Haven’t Actually Seen Afghanistan I consider his latest body of work and book Mountains Of Majeed:

Clark documented the infrastructure needed to support a military base that covers 6 square miles and employs 40,000 people. He photographed everything from the mess halls and laundry to the sewage treatment system, but the colorful murals and paintings dotting the base most intrigued him. They depict an idyllic, romanticized vision of the local landscape and Hindu Kush, one free of war. The reality, of course, was much bleaker, with the distant peaks of the mountains beyond Bagram riddled with conflict and danger.

Read the piece in full.

TORTURE REVELATIONS

It was a double whammy this week. Everyone noticed the 6,000 page report into CIA torture. Many won’t know that today was the day that Justice Department attorneys presented the Obama administrations rationale for suppressing over 2,100 photos and videos of torture by American military personnel in Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Since 2009, the Obama administration has argued that releasing them would inflame anti-American sentiment abroad and place Americans at risk. Federal Judge Alvin Hellerstein of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York is not so easily convinced and wants the government to explain, photograph by photograph, how each might pose a threat to national security. The fight to release these photos dates to 2004, when the American Civil Liberties Union filed a Freedom of Information Act request.

David Levi Strauss has tracked these developments from the very beginning. Several chapters in his new book is Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow (Aperture, 2014) deal directly with the war over control of torture photos.

CONVERSATION

Strauss and I, for WIRED talked about state secrets, how the brain is wired, the political power of images and whether or not photos of Osama Bin Laden’s corpse actually exist.

WIRED: Why has the release of 2,000-plus remaining images and videos made by US military personnel in Abu Ghraib not been resolved?

Strauss: Because of the effectiveness of the images. They became the symbol of the change in US policy to include torture. Images are very powerful. That’s why the US government has become very afraid of the effects of these images worldwide.

The other amazing thing about the Abu Ghraib images was that they crossed the boundary between private and public. That is unusual. It changed things for photojournalism, for the military, certainly, and for the public at large. Prior to the release of the Abu Ghraib images, the military was handing out cameras to soldiers so that they could use photos to stay in touch with their families, and to be used operationally.

Read the full conversation: The War Over the US Government’s Unreleased Torture Pictures.

–

[All images for this Prison Photography post via Salon]

Afghanistan is a very poor country, placed 174th out of 178 in the Human Development Index. The literacy level is 50% for men and 20% for women and the average life expectancy is below 44 years. Only one in three people have clean drinking water and life expectancy is 43. It has suffered many years of war. This is a very challenging environment in which to introduce a formal, state-wide justice system based on written texts, record-keeping, databases (and a regular supply of electricity) and all the appropriate protections for the rights of suspects, defendants and prisoners that accompany such systems in the West.

Source: Alternatives to Imprisonment in Afghanistan. A Report by the International Centre for Prison Studies (February 2009)

Manca Juvan, the subject of a post on Sunday, also photographed in an Afghanistan women’s prison. Juvan is only one of several photographers to take on this subject matter – Anne Holmes, Andrea Camuto, Katherine Kiviat, and David Guttenfelder being others.

The entrance door to Walayat Women's Prison, Kabul. Currently 33 women and 16 children are kept imprisoned. © Manca Juvan, May, 2003

Suhila Fanoos, 25 years old, Walayat women's Prison guard standing in front of the Women's prison holding 32 female inmates for crimes such as skipping home and leaving their family responsibilities. Sign above her head reads "Prison of Women". Photographed in Kabul, Afghanistan July, 2003. © Katherine Kiviat/Redux Pictures

HOW TO APPROACH THESE PHOTOGRAPHS?

The portfolios of Juvan and her contemporaries had me thinking. Many photographs were from 2003 or later in 2007/08 (due to media coverage of allegations of abuse or the construction of a new prison).

I’d like to present a few images, but am I only comfortable doing so if I also provide an accurate summary as it is NOW for women imprisoned in Afghanistan.

Firstly, I just like to point out the two pairings above and below. Kiviat and Juvan (above) both show the same portal at Walayat women’s prison, Kabul. In 2004, one year later, Kiviat also photographed this door which is the same as that shot by Andrea Camuto (below). Camuto identifies the door as belonging also to Walayat women’s prison.

The women's prison in Kabul, A woman speaks to female prisoners through the peep hole of the prison door. © Katherine Kiviat/Redux. 2004

Visitation, Walayat woman's prison, Afghanistan © Andrea Camuto

WAYALAT WOMEN’S PRISON

Wayalat still operates as a prison, but it no longer houses female inmates. A 2003 IRIN report detailed the dire need for humane facilities at Wayalat:

‘According to Lt-Col Habibuallah, in charge of Wolayat prison, the present building with its 17 rooms and four toilets was built some 90 years ago to accommodate up to 200 people. “There are 511 men and 32 women imprisoned here,” he said. There were no categories for offenders and the accused and convicted were generally mixed together, including some inmates on death row. “There are no basic facilities, no ambulance, no proper medicine and health care, and the increasing problem of overcrowded rooms is a tragedy,” Habibuallah said. Even the 35 staff members lacked access to a toilet and were forced to sleep on the roof or in the courtyard at night. “We have worse conditions than the prisoners,” he claimed. Women inmates fare slightly better. Located in a separate building, the painted cells house between five and seven prisoners each, but the lack of adequate health care is felt more by the detained women.’

Manca Juvan‘s work focused on the women and their children in Wayalat. Katherine Kiviat‘s work is part of a larger body of work describing the new roles and careers (including that of prison guard) of women in Afghanistan. The collection is called Women of Courage.

Andrea Camuto‘s work, shot in 2005, 2007 & 2009 followed returning refugees and the “forgotten” women of Afghanistan to the cheaper countryside rents, to the hospitals … and to the prisons if necessary.

The common theme for these photographers is the injustice suffered for many women whose imprisonment is based upon judgement for “moral crimes” and “bad character” including sentences for adultery (which includes inappropriate acts both in and out of wedlock), being drunk, wanting a divorce or even just leaving a husband for a night to stay with family after suffering a beating.

PUL-E CHARKI

On the outskirts of Kabul, Pul-e Charkhi is Afghanistan’s most notorious prison. It has been used by every regime to house it’s enemies.The unearthing of mass graves in 2002 confirmed the Soviets’ use of the site for mass-killings and the Americans adopted and expanded the prison to house Taliban fighters. In 2006, there was a major rebellion and riot by the prisoners.

Anne Holme‘s work from Pul-e Charkhi was conducted in 2007. Holmes’ story is that of the struggle to raise children inside the walls, the quashing of legal rights and despite the “warden’s genuine concern” the inability of the justice system to provide fair hearing for the women.

Pul Charki's womens prison just on the outskirts of kabul is rough living. Inmates do not receive adequate medical attention, they cannot send or receive mail, and many of the women there have yet to learn the crime with which they have been charged. © Anne Holmes

In April 2008, David Guttenfelder visited Pul-e Charkhi. His work, Kids in Prison reveals disturbing figures – “There are 226 young children in Afghanistan’s prisons, including many who were born there. They have committed no crime, but they live among the country’s 304 incarcerated women.”

Jamila, left, plays on a seesaw with children of other female inmates on the prison yard of Pul-e Charkhi prison in Kabul, Afghanistan April 17, 2008. Jamila, age 7, and her mother, Najiba, who is serving a seven year sentence for adultery, have been in prison for 10 months. © David Guttenfelder/AP

Pul-e Charkhi was a brutal living environment. This report details inadequate sanitation, frigid winter temperatures, rape and humiliation.

In the same month that Guttenfelder photographed – April, 2008 – the women and children of Pul-e Charkhi were moved to a new purpose built facility. Recognising the special requirements of female prisoners, Badam Bagh was constructed by the United Nations Drugs and Crime Office (UNODC) with the financial support of the Italian Government.

The two videos below offer some comparison between the two facilities:

PUL-E CHARKHI

BADAM BAGH WOMEN’S PRISON

LYSE DOUCET AT BADAM BAGH

To bring us right up to date, the best reporting is not that in the photographic medium, but straight news reporting. Lyse Doucet‘s report for the BBC is a must see.

(I have applauded Doucet’s journalism in the mens’ wings at Pul-e Charkhi before).

At a moment when the White House is to open talks with the Taliban and the media is comfortably using the phrase “unwinnable war”, it is perhaps responsible to consider the lives of those caught up in the broken justice system of Afghanistan. The prisons of Afghanistan are one of the last priorities for a society that is war torn and divided. Afghanistan hasn’t got the resources to support the basic human rights of those it incarcerates when the rights of those outside prison walls cannot be guaranteed.

“Here” is Pul-e-Charki.

The long and contested history of this complex has eluded my ability to summarise. Lyse Doucet‘s 13 minute report for BBC Newsnight does an excellent job.

Louie Palu, a photographer I much admire because of his past photographic exploits has just secured the Alexia Foundation Grant for Professionals. The $15,000 award will allow Palu to continue his project Kandahar.

NPPA quotes Palu:

I don’t think we will, not in today’s media climate that has swung full circle back to great emphasis on the politics of the nine year old conflict.

See Palu’s full proposal and portfolio at the Alexia Foundation website, and view his video work at the Atlantic.

– – –

Juliette Lynch won the Alexia Foundation Grant for Students.

And despite all her amazing work, I just had to post this image (not from her portfolio) of her celebrating the win! I think it deserves an award itself.

Photo by Andrew Maclean. Bruce Strong and Juliette Lynch rejoice as Lynch is named winner of the 2010 Alexia Student Competition. SOURCE

Well done Juliette.

– – –

The Alexia Foundation for World Peace was established by the family of Alexia Tsairis, an honors photojournalism student at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University who was a victim of the terrorist bombing of Pan Am flight #103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, on December 21, 1988. She was returning home for the Christmas holidays after spending a semester at the Syracuse University London Centre.