You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Female Prisoners’ tag.

Inmates line up for work early in the morning at Estrella jail. © Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA

Yesterday, the Guardian ran a gallery of Jim Lo Scalzo‘s photographs of a female chain-gang in Maricopa County (Phoenix), Arizona.

To people who are unfamiliar with the chain-gangs, established by the controversial Sheriff Joe Arpaio (the self-titled “Toughest Sheriff in America”), Lo Scalzo’s images may be a shock. Certainly, they are fascinating.

Unfortunately, this is not an example of a photographer gaining exclusive access to an invisible institution. To the contrary, inmates of the Maricopa County Jails are arguably the most frequently photographed prisoners in the United States. Approach Lo Scalzo’s work with caution.

Jon Lowenstein photographed the female chain-gangs in March, 2012 and Scott Houston photographed the all-female chain-gang when it was first established almost a decade ago.* These are only three photographers of hundreds who have visited Tent City, Estrella Jail and followed chain gangs out on to the streets.

The Guardian writes in it’s brief introduction, “Many women volunteer for the duty, looking to break the monotony of jail life.” That might be true, but it is also the message peddled by the Sheriff’s office and it also stops short of asking why these women have been ushered into the jail system. I should say at this point, these are women on short sentences locked for non-serious, probably non-violent offenses, likely drug use, prostitution, petty theft. If I may generalise, they are a nuisance more than they are a danger. They are victims as much as they are victimisers.

What must to do with Lo Scalzo’s photographs – and with others like his – is appreciate how they were made; more specifically we must appreciate the pantomime that is put on display for the public and put on for the photographer.

I have spoken to many photographers who have described how Arpaio directs a “media circus.” I have written before about his press-staged march of immigrant detainees through the streets of Phoenix. He dresses citizens serving time and non-citizens awaiting immigration hearings in the same pink underwear and striped jumpsuits.

Let’s not deny that Sheriff Arpaio is on message, dominates message and understands visual symbols and the power of the image probably as well, if not better, as any of us who make, discuss and revel in photography.

There is certainly a lot more to be teased out about Arpaio’s near 20 years in office and his media savvy, but now I’d like to turn our attentions away from photography and towards a socially-engaged art project of admirable sincerity and complexity which might teach us more about Maricopa County than photographs alone.

Throughout 2011, Assistant Professor of Multimedia Gregory Sale at Arizona State University (ASU), carried forth It’s Not All Black & White a program of talks, installation and interventions at the ASU Art Museum.

It’s Not All Black & White intended to give “voice to the multiple constituents who are involved with the corrections, incarceration and the criminal justice systems.” To establish a discussion around the highly contested issues in a divided community, Sale and his team had to rely upon the trust and input of museum curators, university faculty, students, sheriff’s deputies, incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, family of the incarcerated and so on and so forth. It is quite remarkable that under the same banner, Sale was able to invite Angela Davis to talk and in another event invite Sheriff Arpaio to a discussion on aesthetics.

Round table discussion at ASU Museum. Joe Arpaio on the right.

Incarcerated men were brought onto university grounds to paint the stripes in the ASU museum, Skype dance workshops were done to connect incarcerated mothers and daughters; the museum space was repeatedly given over to engagement instead of objects.

At the fantastic Open Engagement Conference, I shared a panel with Gregory. He said that for so long Sheriff Arpaio had controlled how people think of stripes and think of criminality in their community.

Gregory said one thing that really stayed with me. He said that for a brief period while It’s Not All Black & White was in the museum and the programmes went on, he was able to wrestle that control away from Arpaio and open a discussion that focused not on the blacks and the whites, but on the grey areas. In those grey areas are hard decisions and hard emotions. But, also in those grey areas, are solutions to transgression in our society that might look to root causes and solutions that engender hope and spirit-building instead of humiliation and penalty.

When we look at Lo Scalzo, Lowenstein, Houston and the works of countless others from Maricopa County we need to bear in mind the stripes and the spectacle of the chain gang is deliberate. Are the photographs showing us only the black and white of the stripes or are the photographs introducing us to meditate on the grey areas? I suspect they do mostly the former.

*Lowenstein had photographed immigrant detainees in Maricopa County’s ‘Tent City’ a few years ago. I included both Lowenstein and Houston’s work in Cruel and Unusual.

“Curiosity was the initial spur. Surprise, shock and bewilderment soon took over. Rage propelled me along to the end.”

Jane Evelyn Atwood on photographing in women’s prisons.

This is the third and final installment in my series Women Behind Bars. The second part looked ta the writing of Vikki Law and the first looked at the journalism of Silja Talvi. It was Silja who recommended Jane Evelyn Atwood’s work.

When discussing the work of a prison photographer, it is preferable to do so within the specifics of the region or nation they document. Prison Photography‘s key inquiry is how the photographer came to be in the restricted environment of a prison and these details differs from place to place. Such inquiry is complicated by Jane Evelyn Atwood‘s work because she visited over 40 prisons in twelve countries over a period of one decade. In some cases I know the location of a particular image and in others I don’t. I suggest you compensate for this by buying the book Too Much Time for yourself.

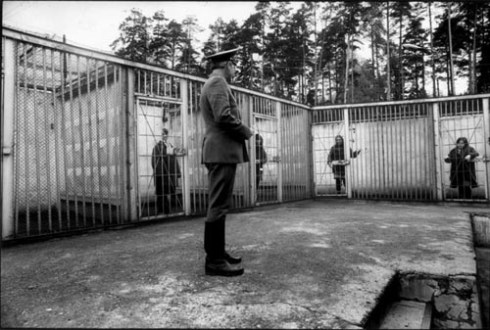

Above is a women’s penal colony in Perm, Russia. It holds over 1,000 women – the majority of who work forced hard labour. Here we see women who are in solitary confinement experiencing their yard privileges – half an hour in outside cages. Most women in the prison are there for assault, theft or lack of papers.

Below is a scene from a Czechoslovakian prison. The scars are not the result of genuine suicide attempts but of regular self-mutilation – a problem more common among female prison populations than male populations.

Another reason to pick up Atwood’s book would be that there isn’t much stuff out there on the web – and that which is is low resolution or small-size. You can see a small selection from Atwood’s Prison series at her website; small images at PoYI; and a really good selection of tear-sheets at Contact Press Images.

By far the best stuff on the web concerning Too Much Time is an Amnesty International site devoted to the project. It includes a powerful preface in which Atwood lays out her raison d’etre. Next Atwood provides a “world view” comparing the prison systems of France, Russia and the US (each a five minute audio). Then comes three specific photo-essays with audio (Motherhood, Vanessa’s Baby, The Shock Unit). Finally, Atwood provides six stories behind six photographs. The stories are many and the facts more astounding than the emotions.

While Atwood’s pictures present the many individual circumstances of the prisoners, Atwood has identified a common denominator; “Of the eighteen women I met in [my] first prison, all but one seemed to be incarcerated because of a man. They were doing time for something he had done, or for something they would never have done on their own.”

Atwood qualifies this, “One woman told me her husband forced to set the alarm to have sex with him three times a night. She endured it for years and finally killed the man that kept her hostage. Another woman’s husband was shot by her daughter after he had stabbed her in the arm as a “souvenir”, poured hot coffee on his wife’s head for not mixing his sugar, and urinated all over the living room after one of the children refused to come out the bathroom. The woman was serving time for “refusing to come to her husband’s aid.”

What is most impressive about Atwood’s work is that it predates photojournalism’s wider interest in prisons by a couple of decades. She had at first tried to gain entry into a French prison in the early eighties. Her failure is unsurprising given Jean Gaumy of Magnum was the very first photojournalist inside a French prison in 1976.

It is a scandal that the discussion over shackling women during labor and gynecological examination continues today. Atwood captured the brutality of it decades ago.

Atwood’s work veers consciously between two reality of the women’s situation – the environment and the body.

Many of her photos share a compositional austerity. The hard angles of institutions run according to ‘masculine mathematics’ (dictating sentencing and experience) are repeated. Atwood punctuates this stern reality with flourishes of femininity … and touch.

Some may think Atwood has over-reached herself with a global inquiry and I’d be sympathetic to the point if anyone else had come close to her commitment. Even considering each prison system in isolation, Atwood’s work can hold its own. Her work in Perm, Russia is particularly powerful as it orbits closely around the issue of uniform, identity and the complications it brought to bear directly on her documentary.

At the Amnesty site, Atwood brings up many interesting points of comparison. She identifies the US system as the most sterile with a legal mandate to treat female prisoners in the same manner as male prisoners. But she also says that if there is grievance or complaint to be settled, US prisoners have recourse to do so. Such allowances are not made in France.

On the other hand, children are excluded from all but a couple of US prisons. The security threat is cited as the reason: a child inside a prison is a constant vulnerable life and constant hostage target. The claim seems a little bogus when penal systems of other countries are brought into consideration.

Atwood was interviewed by Salon about the project. She has also worked on landmine victims and talked to Paris Voice about that. Here, she talks about Canon about her work in Haiti.

Jane Evelyn Atwood

Biography: Jane Evelyn Atwood was born in New York. She has lived in Paris since 1971. In 1976, with her first camera, Atwood began taking pictures of a group of street prostitutes in Paris. It was partly on the strength of these photographs that Atwood received the first W. Eugene Smith Award, in 1980, for another story she had just started work on: blind children. Prior to this, she had never published a photo.

In the ensuing years, Atwood has pursued a number of carefully chosen projects – among them an 18-month reportage of a Foreign Legion regiment, following the soldiers to Beirut and Chad; a four-and-a-half-month story on the first person with AIDS in France to allow himself to be photographed for publication (Atwood stayed with him until his death); and a four-year study of landmine victims that took her to Cambodia, Angola, Kosovo, Mozambique and Afghanistan.

Atwood is the author of six books. In addition, her work has been including the ‘A Day In The Life’ series. She has been exhibited worldwide in solo and group exhibitions. She has worked for LIFE Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, Stern, Géo, Paris Match, The Independent, The Telegraph, Libération, VSD, Marie-Claire and Elle. Atwood has worked on assignment for government ministries and international humanitarian organizations, including Doctors Without Borders, Handicap International and Action Against Hunger.

She has been awarded the Paris Match Grand Prix du Photojournalisme (1990), Hasselblad Foundation Grant (1994), Ernst Haas Award (1994), Leica’s Oskar Barnack Award (1997) and an Alfred Eisenstaedt Award (1998). In 2005, Atwood received the Charles Flint Kellogg Award in Arts and Letters from Bard College, joining a company of previous laureates including Edward Saïd, Isaac Bashevis Singer and E.L. Doctorow.

Fabio Cuttica‘s 2006 photo essay in Nerve from the Buen Pastor (Good Shepherd) Prison, Bogota was brought to my attention via industry-insider Rachel Hulin’s A Photography Blog. She describes a well-rude awakening.

If you can get past this description from Hulin’s subconscious, I encourage you to think about the merits of this particular pageant. Despite the obvious interest from media (who are unlikely to refuse such a unique/titillating story) the benefit here seems to be predominantly for the women of the institution.

The pageant in is honour of the Virgin Mercedes, the patron saint of prisoners. Ada Calhoun – in the intro for the Nerve photo essay – hams up the language to sensationalise the event, but I don’t think there is a need. Cuttica’s photographs are brimming with the fun, the nerves, ecstasy and community of the event.

It is obviously novel day. It would seem to me that the opportunity to celebrate femininity and to express notions of beauty normally obscured by the institution would be a welcome relief for many female prisoners; I hope its a hell of a lot of fun.

But, this is a curious contradiction to how I usually feel about beauty pageants. I generally consider beauty contests as shallow, if not ridiculous. They make a whole lot of noise over very trivial matters. To my mind, a beauty contestant on stage is as pathetic as a dog in a sweater; cringe-worthy, vulnerable and compromised.

I suppose an answer lies in who has the power and the organising authority. I may be wrong, but I presume the women of Buen Pastor prison have a huge investment in the pageant – supporting their friends, stage preparations, making costumes and accommodating guests to the prison on their day.

This is, of course, in contrast to the usual female beauty contestant who is likely genderised by her community, normalised into swimsuit & high heels at an early age and conditioned to not question the strange gaze of a town’s older (men) folk.

Fabio Cuttica resides in Bogota, Colombia. His work is distributed by Contrasto & Redux agencies. He has worked across Latin America, recently winning acknowledgment from the College Photographer of the Year for his work documenting the La Maria & their struggle for land rights in the Cauca Region of Colombia. In 2008, Cuttica was honorably mentioned at the National Press Photographer Association’s Best of Photojournalism Awards for his extended essay about gang violence in Barrio Petare, Caracas, Venezuala. He has also worked on assignment for GEO about the Basque Region of Spain and covered the traditional family life and weaving in Valledupar, Colombia.

Copyright: Angela Shoemaker

Angela Shoemaker, visual journalist and graduate of The School of Visual Communication at Ohio University, informs us, “Ohio Reformatory for Women (ORW) nursery, one of four such programs in the U.S., offers a unique opportunity for female inmates to keep their babies while serving out their prison sentences.”

Angela has also produced Prison Nursery: Keeping Mothers and Babies Together in an audio slideshow format Prison Nursery.

I came across this image on a ‘free media web hosting site’ where I lazily put in the term “Prison” to the search. I am unwilling to name the site as I do not wish you to suffer the same banner ads and unedited content.

Women prisoners working on road, Tanzania. circa 1901. Source: Unknown

The search returned the usual images of pets in crates (1st-person caption optional), macro-shots of rusting locks and/or bars, stock images of barb wire, and photos from Eastern State Penitentiary (which does many photography workshops). There were three images that were worth a second glance – the other two being images WWII prisoners of war.

Despite having no means to confirm its authenticity or the accuracy of the caption, I thought the image worthy of a quick reflection. The image is contrary to the usual representation of incarcerated peoples – the era; the gender of the subjects; the continent; the anonymity of the photographer. De facto, this becomes a visual source in its most naive understanding; all we have to go on are the women depicted. The photograph wriggles away from all the contextual information one needs to assess its political purpose.

The responses of the women to the camera (pride, defiance, awkwardness, subjection – and even laughter from a lady in the background) compel me to presume nothing of this picture. I question the authority to which they are subject, I question the legitimacy of the charge by which they are held prisoner, I certainly can’t reconcile hard labour with a mode of justice for grown women. This is a depiction of slavery more than it is of criminal justice.

If the date in the caption is accurate, Tanzania (then Tanganyika) was under German rule. “Tanzania as it exists today consists of the union of what was once Tanganyika and the islands of Zanzibar. Formerly a German colony from the 1880s through 1919, the post-World War I accords and the League of Nations charter designated the area a British Mandate (except for a small area in the northwest, which was ceded to Belgium and later became Rwanda and Burundi). British rule came to an end and Tanganyika became officially independent in 1961.”

I rarely harp on about “the power of photography” because it is a subjective assessment, but I will vouch for that personal reaction to imagery that can stop you in your tracks and get you thinking.

I have been supremely busy lately. I have eight projects in various stages of draft, but want to throw up some quality images, accompanying words and give a general shout out to Bangladesh’s photographic community.

Through my day job, I am familiar with Shahidul Alam‘s fine photography. I am more impressed by his stewardship of his nation’s photojournalist community, here, here and here. It was at Alam’s Blog that I discovered the images of Momena Jalil. I’ll simply repost the photographs and let them and the text speak for themselves.

They were some 21 women. Some with with children who were free but had nowhere to go. So they stayed with their mother in captivity. It was a rare chance for us; it was the opening of the new women’s prison on eight acres of land situated on the Western edge of Kashempur. We were allowed because we were women and in those ten minutes we learnt what we could not have learnt in a lifetime. Losing one’s freedom strips us of the right to live. It is the strangest feeling, a chilling feeling. Freedom denied is freedom lost in the cradle of the life.

Cell, Momena Jalil, 2008. Having spent a year in prison already, 25-year-old Rahima still cannot reconcile with her living conditions.

‘It is difficult to cope with all that goes within the walls of a prison,’ she says. ‘There were times when the prison guards molested me…they do sexually abuse women,’ she says softly, hiding her face behind her white saree. As soon as the guards walk in her expression changes and she mutters, ‘we have no problems at all.’

From Jalil’s post it is obvious the system has affected the women very differently.

‘How can you not love the darkness, the stench, the suffocation and the crowds?’ asks fifty-year-old Khaleda in her raw husky voice. Her big eyes and rough expressions complement her loud and dominating voice. ‘After spending twenty-five years I don’t think I would ever want to go back. I get a taste of everything here – be it having tonnes of friends or being tortured, all of it is ‘fun’, she says sarcastically.

Khaleda knows the secrets of the prison, yet she refuses to speak up. ‘You know why I came here? My husband married another woman for no reason. He brought her home with her two children. I had done nothing. But he still did that. So I ate the two kids,’ she laughs aloud. ‘And then I got involved in a trafficking case and a lot more.’

In twenty-five years, Khaleda has seen the darkest sides of the prison. She has lived inside crumbled cells with no space to even sit or breathe. ‘I don’t like the idea of being moved to this new unit of the women’s prison. I love the people there. The Dhaka Central Jail is overcrowded, stinky, a torture hole but it’s still been my home for the past so many years,’ she says.

Khaleda is one of 200 women who are waiting to be shifted to the first female jail in Kashempur that recently opened.

She was a mother, a daughter, a sister, a home-maker, a beloved wife but today she is only a prisoner behind bars serving a life sentence. She could have been many things but situation, time, circumstance and fate took all her rights to live free in society. Society finds them unfit because they cross the line of the law; they were not born to be criminals but time took them where they committed crimes… some killed step-children, some were found trafficking in-between borders, they were too many and we had too little time to know what crimes they were in for. We had ten minutes, the guards were rushing us, it’s unthinkable to let journalists roam inside a prison. But we have been there, my colleague and I; we saw faces up close, people who live among us, their faces hold the rumours of sisters, mothers…