“I want this thing off today … this fucking thing is an invasion of privacy, and goes against my well-being,” said the young boy about his ankle bracelet. He was speaking to Zora Murff, a BFA photography student at the University of Iowa and also a Juvenile Tracker for the Juvenile Detention and Diversion Services (JDDS) of Linn County, Iowa.

It was only when Murff heard this complaint that he began to wonder if he and his camera could interrogate the issue of control.

“He was angry,” recalls Murff. “The more I thought about his anger, the more I pondered the concepts of privacy and control in the juvenile corrections system and the role that I play inside of those concepts. I interact with these youths at a critical point in their lives where control is an integral part of the day-to-day. My job is to be a consequence, to insert myself into their lives […] while the adolescents themselves are struggling to exert control over their development.”

Linn County JDDS provides monitoring and rehabilitation services to youths on probation. Murff has been in the job eighteen months. In mid-2013 he began to photograph his employment and construct a project for submission as part of his studies.

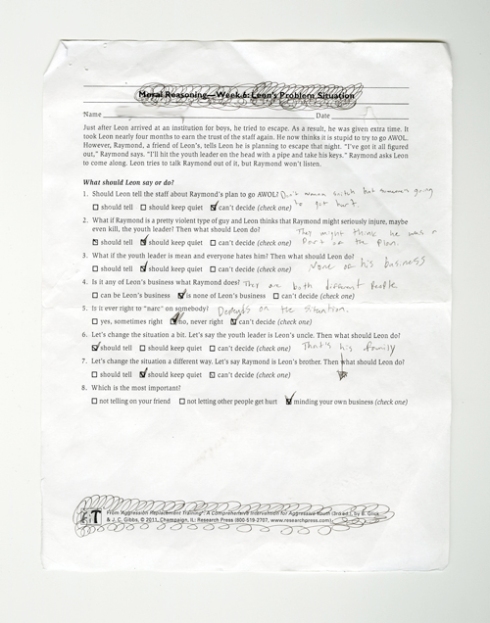

The resulting series Corrections is made up of: photographs of locations of interaction with accompanying narratives about the transgression that took place there (images below with captions); anonymous portraits of the youths; handwritten reflections of the youths; and official paperwork and service documents.

Murff published his notes during the series on the Corrections Tumblr. He has self-published a limited edition book (Murff welcomes interest from publishers to do a larger run). Murff is taking a temporary hiatus from the project. Last week, my Wired colleague Jakob Schiller wrote about Corrections in the piece Peering Into the Digitally Tracked Lives of Youths on Probation. I wanted to do a bit more digging and ask Murff about the logistics, motivations and relationships inherent to the work.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Three youths broke into an abandoned home on the northeast side of Cedar Rapids. When Cedar Rapids Police responded to the scene, two of the youths surrendered themselves, while the third attempted to hide in the basement. Officers sent in a K-9 to retrieve him. Each youth was charged with criminal trespassing and disorderly conduct.

Q&A

Prison Photography (PP): Can you start by describing your work?

Zora Murff (ZM): Tracking is one of the diversion programs that JDDS offers. Diversion refers to the youth being able to stay in the community, rather than being placed in detention or in a different type of placement like residential treatment. My primary responsibility is monitoring youths on probation. I have face-to-face contact with youths on a regular basis to ensure that they are complying with the expectations of their probation. This may entail electronic monitoring, urinalysis, school follow-up, transportation to therapies (substance abuse, sexual offense, anger-replacement), and other things like completing community service hours. My caseload fluctuates – I believe the lowest number I had was nine youths and I have had up to twenty-one.

PP: Would you have managed to gain access if it weren’t for your job?

ZM: When I pitched the idea to my supervisor, she was very intrigued, but being an insider definitely gave me a leg up, and I was very lucky to have that level of access. My supervisor had a few specific guidelines, but gave me free reign, so I had a wide creative space to work with. I think there was a level of trust there, which made Corrections possible.

PP: How did you come to be studying photography if you’re also a probation service employee?

ZM: I started my degree in psychology. My professional background in human services started when I replied to an ad on a campus bus. I needed a job. I started in disability services working with a wide population of people. Those experience helped me get a job with juvenile criminal justice. I didn’t necessarily have a desire to work in this specific area, but it has been a great experience to watch the youths grow throughout the probation process.

I love my work but I have always felt I was missing out on a need to create, a desire to teach, and a love of the photograph. That is where my education in photography comes into play.

PP: Juveniles under the control of the state are vulnerable young adults. What sort of assurances did you have to provide for your employer, the children and the parents/guardians?

ZM: I have noticed that when working with any population in human services, it all comes down to trust. The real question is how do you build that trust with the people that you serve. I think that this can vary with any worker, but I usually broach this by being available and consistent. Having trusting relationships with the youths that I photographed was key to working on this project.

The biggest assurance that I had to provide was anonymity. It was also important to explain my project to them, which isn’t always easy to do, especially when I was starting out because I wasn’t sure where the project was taking me.

PP: Is Corrections about delinquency or about control; about youth or about state?

ZM: All of the above. The youths do delinquent things that warrant some type of intervention and I wanted to document their experiences once they become a part of the juvenile corrections system. Youths are attempting to control their lives while workers are trying to exert some sort of control over it for them. There’s a dynamic at play between the two.

The use of narratives and documents add context to the project. I felt that portraits of the youths, while the most important component of Corrections, would have told an entirely different story if they were to stand alone.

PP: Is Corrections a voice for you or for your subjects?

ZM: I wouldn’t say that Corrections is my voice personally. The youths are allowing me to show them through their portraits and through some of their writing. My intent was to approach it from an ‘anthropological’ standpoint if you will, almost as if I am a recording device. I felt that it was important to provide a window into this world without editorializing, even though I am embedded in the system.

I feel that when it comes to children on probation a lot of stereotypes are thrown around and it would have been easy to fall into tropes. I want viewers to see inside of the system and draw their own conclusions.

While hanging out with friends, a youth started verbally harassing a peer walking home from school. The youth started to follow the peer and punched him from behind in the side of the face. The youth continued to assault his victim until a car pulled up in the alley. While fleeing the scene, the youth kicked his victim in the head. The youth decided to turn himself in when the story aired on the local evening news, and told Cedar Rapids Police that he had no justification for the assault, that he was just, “mad at the world.” The victim was hospitalized for two days with a broken jaw, two teeth knocked out, and a severed facial nerve. The youth was convicted of felony charges and placed at the Eldora State Training School.

PP: How has the project effected your relationships?

ZM: In human services, the work is about the person that you’re serving, not about you, and typically sharing personal information is discouraged. However, I feel that opening up about my passion for and education in photography bought me a little more trust with some of the clients. It was kind of odd, really. The kids were either totally interested and invested in the project, or completely indifferent. When I walk through the detention center, one or two kids will ask if I’m still working on the project or what was my grade in my photo class. I have also earned the moniker, “that guy with the camera.”

PP: Any particular stumbling blocks?

ZM: My biggest barrier was not being able to photograph faces – I didn’t want to blur out faces or put bars over them. It almost became a game figuring out how to make faces unidentifiable and have the photographs be meaningful.

PP: Any pleasant surprises?

ZM: A number of the compositions happened by accident – a kid blocking the sun from his eyes, or deciding to sit in a certain spot. There is one photograph of a youth playing guitar in his bedroom. While we were taking the photograph, the youth’s friend came to the bedroom window and had a perplexed look on his face when he noticed me with the camera. The youth told his friend that he had just been signed to a record label and that I was from Rolling Stone Magazine. We all had a good laugh about that – and it was a welcome change from the more difficult interactions that I have.

PP: What has been the reaction so far to the work?

ZM: So far, reactions have all been pretty positive. I was part a group exhibition for the class Corrections was completed for, and a number of people drew some sort of sentiment from the photographs. I also had a portfolio review at Midwest SPE last year, and the project was received well. However, I understand that working with a vulnerable population, specifically youths, can be a contentious territory so I have been a pretty hard critic on myself about the work.

PP: Do you plan to continue photography and/or work in criminal justice?

ZM: I would like to teach photography as a means of creative expression to youths at the detention center, but that is just a lofty idea at this point.

PP: It would be wonderful if you could achieve those types of workshops.

ZM: There are definitely some barriers. The biggest obstacles would be finding the time to teach a course, funding for materials, developing a curriculum, and figuring out when it would work into the residents’ schedule as their day at the detention center is very structured.

PP: What makes you think photography is useful for the youths? What skills does it teach? What can be achieved with photographic education, particularly to at-risk youth?

ZM: Any creative outlet is useful to children. I remember having a drawing journal when I was a teenager, and the amount of things I was able to work through by drawing.

Photography could be a good outlet for youths in the detention center as I feel that visually investigating their surroundings would allow them to build a sense of self-awareness, getting them to really consider where they are in life and where they would like to go.

Also, with the concept of control again, a number of the interactions that I have are usually based upon the youth feeling that they don’t have a say with what is going on in their lives and they are being told all of the things that they cannot do, the places that they cannot go, the people that they cannot hang out with. My hope is that by introducing them to photography this will provide them with a chance of self-expression – they can decide what they want to photograph and how they want to photograph it, getting some semblance of control back.

PP: What else are you up to?

ZM: I’ll continue Corrections until I reach a place where I feel that it is as complete as possible, but I am taking a break from it for the time being. I have an idea for a more intimate project, a case study of sorts, following the story of one individual on probation. I’m gearing up to start shooting for this project in the next few months, and have a youth interested in being a part of it, so I’m ironing out details.

PP: Is the camera a security device or an artistic tool?

ZM: Part of my statement for Corrections is how I, as a Tracker, am required to impose on these youths. This was problematic for me at times because by pointing my camera at them I was imposing upon them in an additional way, but it is important to understand the difference. The cameras that we use to surveil youths are all there in a reactionary capacity in order to provide some sort of control. With my camera, I too am recording, but my camera is there in a collaborative capacity – I feel that the youths have taken back a level of control as they have allowed me to portray them and document their experiences.

PP: Thanks Zora.

ZM: Thank you.

2 comments

Comments feed for this article

December 11, 2014 at 2:00 pm

I’ll Be Contributing To The Marshall Project | Prison Photography

[…] you want to learn more about Zora Murff’s work you might be interested in this long interview I did with Murff on Prison Photography in January, […]

November 23, 2015 at 2:29 pm

Zora Murff’s Photobook ‘Corrections’ Out Now! | Prison Photography

[…] his debut book Corrections. Of course, I jumped at the chance. I’m a huge fan of the work. I interviewed Murff at length in January 2014 and I wrote about Corrections for the Marshall Project in December […]