You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Donald Weber’ tag.

“The unseen subject of these photographs is Power. They show us the human limits to the understanding of Power. There are many things we don’t know about Power. We don’t know if Power is the same everywhere, if its manifestation in one place and time is meaningful, measurable, subject to the same laws as another.”

– – Donald Weber, ‘Confessions of an Invisible Man’, Interrogations, pg. 158

Given that Donald Weber‘s Interrogations has just been awarded a World Press Photo award in the Portraits category, now is a good time to look at the book of the project.

– – –

At passport control my fingerprints flagged an “interaction” with the police authorities five months prior. Directed to a waiting room, I was told to take a seat and remain there until a customs and immigration officer could clarify the details of said interaction.

I wasn’t told how long the wait would be.

Thumbing around in my bag for some reading material to pass the time, I broke a wry smile when I pulled out Donald Weber’s Interrogations. He’d mailed it a few weeks prior. This was the first chance I’d had to look it over.

– – –

Held by a stitched spine, the 160 pages taper to the centre on the outside edge of the book (see image above).

Weber and publisher Schilt also made the decision to bind it in the same wallpaper stock that hangs on the wall behind many of the detainees. Weber has come to see the modern State as “a primitive and bloody sacrificial rite of unnamed Power.” The choice of the outmoded wallpaper is an unnerving nod to the Power of a throwback era and brings us closer to the outmoded policing within these outmoded spaces.

Weber spent months – possibly years – building a rapport with the police department in order to sit in on their questioning and to make photographs. “I would just sit there from 9am in the morning to the evening, and just wait. I went days without actually taking pictures. It’s a game of chicken, and I always flinch last,” Weber told Colin Pantall. I’m a little disappointed Weber doesn’t provide the name of the station or town it is in. All we know is that it is in Ukraine.

Interrogations is an unorthodox, shocking and depressing portraiture project. A juvenile, with words scrawled on his forehead in black marker-pen, sobs; a woman in a dirty sheepskin coat resembles more a carcass than a human; in a sequence of three images we witness one detainee first, terrified; second, threatened by an open palmed strike; and third, with a gun to his temple.

– – –

I was sat awaiting the inconvenience of an unnecessary interview, but I was certainly not awaiting the psychological and physical abuse meted out to Weber’s subjects.

After our brief chat, the immigration officer asked me if I had any questions and assured me I wasn’t on camera. In a relatively powerless position, to not be recorded was a small victory, I considered.

– – –

This idea of being seen during an interview goes to the heart of Weber’s series.

– – –

Here I was, subject to networked systems of law enforcement and U.S. Homeland Security, but I could be sure I’d not face the intimacy of abuse depicted in Weber’s photographs.

– – –

The strength of Interrogations is that it teeters on an ethical dilemma: should Weber have been present? In attendance, was Weber complicit? Are his photographs further abuse and violation?

The answers to these questions are ones that Weber is happy to take on and he has done so in public forums here on Prison Photography and also at Colin Pantall’s blog and at DVAFOTO.

The answers are also easier to find than we might think.

I’d argue Weber’s presence had little to no effect on the behaviours of the interviewers. Given the time he spent in interrogation rooms (evidenced by 51 portraits no less) I’m inclined to subscribe to the reasoning that eventually a photographer’s presence is taken for granted/forgotten and behaviour is less and less effected by the camera-wielding observer.

Diane Smyth, for BJP, describes the interrogations as violating theatre, “Igor and his partners play good cop, bad cop (“or actually, really bad cop, and bad cop”), using threats and intimidation to break the suspects they are questioning in the seemingly anodyne pink room.” Weber sat in the stalls, watching.

One presumes that if Weber’s attendance did alter activities it was to lessen the abuse, not escalate it?

When we are faced with decidedly uncomfortable (abusive) scenes in photography, we cannot help ourselves but to think of the photographer as in some way complicit. This is a sure way to derail inquiry; it is an emotional response that centres on the act of photography instead of the subject. As Susie Linfield lays out in The Cruel Radiance, photography of atrocity can as easily provide an opportunity to dismiss the act, distance ourselves from the images, and move away from topic at hand.

Weber’s work is in our face, but that doesn’t mean we should turn away. An illustrated prologue of Weber’s six years in the former Soviet provide some context for Interrogations. These darker, exploratory more ambiguous images temper a presumption that Interrogations was a smash-and-grab job; we know Weber spent years in the region and that he built-up to this particular project.

Similarly, Weber’s essay, ‘Confessions’ and Larry Frolick’s epilogue provide insight into living within the milieu of policing, crime and punishment in Russia and Ukraine. These elements of the book together provide opportunities for us to enter into the complex society in which Weber lived and worked.

Bluntly put, the superimposed dilemma of a photographer’s ethics are the least of the concerns for the people in the region and in Weber’s photographs.

Weber provides no caption information for his subjects. Did he ever have access to it?

In his brief essay, Weber is aware of his role as photographer within a web of power (with a capital P); how else would he be granted entry to interrogation rooms? Weber puts the meaning of his photographs not fully on the lives of his unknown subjects, but in the context of institutional power.

“We do know that Power is dangerous and exhilarating,” says Weber in the book’s essay, “It expands in proportion to its invisibility.”

With that, instead of asking what does it mean for a photographer to witness institutional abuse, we should be asking what does it mean when there is no witness, photographer or otherwise?

Interrogations, (160 pages) by Donald Weber (2011)

Published by Schilt, Amsterdam.

Designed by Teun van der Heijden of Heijdens Karwei, Amsterdam.

Printed by Wachter GmbH, in Bönnigheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Distributed by Thames & Hudson worldwide. Distributed by Ingram in North America.

Prostitute & Drug Dealer. © Donald Weber

Last year, Colin Pantall and Prison Photography ping-ponged some responses with Donald Weber about his series Interrogations.

Now, Tony Fouhse at drool has had Weber’s ear.

In an enclosed room of interrogation, subjugation and bullying, audiences are likely – again and again – to pose questions about the photographer’s responsibility … or his sanity … or his stomach. Tony Fouhse does so but in a way to give Weber a platform to explain his approach to photography as it relates to Interrogations:

“I think the only way to get anything of sincerity or honesty is to dedicate yourself to something. I guess it’s an old fashioned concept, this idea of sincerity in an age of strict irony. I am a believer in a very slow working method.”

“I believe there is no judgment in these pictures, and that is what is strong and makes an iota of sincerity. Don McCullin called it the “Composition of Empathy,” a direct counter to the Bresson way of photographing, where often it is about the “Composition of Composition.” I take that to heart, and truly I am just interested in who is in front of me.”

“I am not a stylist or even a very sophisticated photographer, compositions are left to the detritus of the roadside… Time allows you to journey past a superficial creation, to “make” a photograph really isn’t that difficult, but to move beyond, and try to offer at least a glimmer of your subject, who they, what they feel, what they think, is the mark of a great photograph.”

____________________________________________________________

Donald is represented by the photo agency Vll Network. Donald Weber’s book INTERROGATIONS will be available this fall. Donald’s website is here.

Dvafoto’s Interview: Donald Weber, inside the Imperium from 2008 fleshes out Donald’s influences, philosophy and trajectory up until that point.

UPDATED: 9:30AM PST, NOV. 10TH

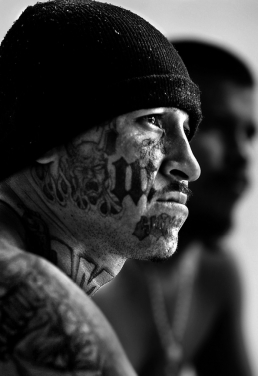

Car thief. © Donald Weber / VII Photo

Since first coming across Donald Weber‘s series Interrogations, I wondered how the hell Weber got the shots and how he handled the ethics of the work. Colin Pantall tapped him up and got some answers.

Weber:

“Watching the methods was not pleasant. Humiliation, violence, degradation. How could you not be repulsed? But the reasons I was there were not for judging them, but was to actually show something very special in the terms of the secrecy of the act. I made a special document precisely because it was about the ‘absence of the void,’ that it showed humans at their most vulnerable and most cruel. This series could easily be judged along the same lines as a war photographer that constantly gets criticized for not doing anything, for not jumping into the fray.”

I’m going to sit on the fence on this one, but I can see a lot of criticisms heading in Weber’s direction. I will say that this is not a cheap project; Weber has demonstrated his commitment to the former Soviet countries.

If we demand photographs to make us think, photographs to show us things we would not otherwise see and for photographers to be cognisant of – and close to – communities in which they work, these are the types of images that will result.

UPDATE

9:30AM PST, NOV. 10TH

As you know, so often I think it is important that a photographer really describes the circumstances of their work. Donald Weber must be aware that I harp on about access (as it relates to photography in prisons) because he emailed me and asked me to pass on this information:

Weber:

“As you know, I’ve spent almost six years living and working in this area. On my very first trip I met a police detective with whom I got along with. Over time, we developed a bond and a trust. Every trip I would bring him photographs and was always very upfront with my work, who I was and what I was doing. Never hiding the results, however critical they may be of him and the methods the police employ.”

“About five years ago I witnessed my first interrogation, and was utterly shocked at its violence, not just physically but mentally as well. Solzhenitsyn talks for almost a third of his book The Gulag Archipelago about the nature of interrogation, and the importance of the interrogation not just through Soviet history, but universally. He would think everyday about the moment of his interrogation how he was broken, and everyday about the moment of his execution. So, the seed for this story was planted.”

“For obvious reasons I could not just ask to photograph inside an interrogation. As my work progressed, so did my police contact, who rose over time to the rank of Major. He had gained a position of authority to grant permission. Since we had spent so many years together photographing, he was aware of my methods and how I worked. We rarely spoke to each other, during work or after hours. I felt it best to maintain as much distance as possible but still respectful of his role. When he finally granted permission he still made me work for the access to the actual accused.”

“I sat almost everyday for four months on a bench in a hallway of the police station waiting with the people who were to be interrogated. The first month, not a single frame was photographed. Each day I would show up 9am, and leave approximately 12 hours later. Most days were spent with nothing to photograph, many of the accused were not interested in having there photo taken. On average, I was lucky to photograph maybe two people a week over a four month period.”

“This was not simply a case of walking in saying hello as a privileged Westerner and flashing my camera around. This was a project five years in the making. So before anybody rushes to quick judgement, I felt the facts as to how the work was created should be shared.”

Last week, when Foto8 ran Katarzyna Mirczak‘s article about of the detached and preserved skin of prisoners’ tattoos, I was, of course, compelled to post about it. But, in truth, I need to do a lot more than duly note a story published elsewhere.

HOW HAVE PHOTOGRAPHERS TAKEN ON THE SUBJECT OF PRISON TATTOOING?

The simple answer is with limitations. Photography can describe tattoos very precisely, but description is not comprehension. Often, prison tattoos are a tactically guarded language.

Even if tattoo symbols are deciphered, they may carry different meanings in other cultures. Prison systems exist across the globe, within and “outside” different political regimes, thus the tattoos of each prison culture should be considered according to their own rules – and this caveat applies even at local levels.

Janine Jannsen offers a good introduction to the history of different tattooing cultures. She summarises tattooing in “total institutions” (navy, army, the penitentiary); tattoos and gender; and tattoos and the demarcation of space.

With regards to prison tattoos, maybe it helps us to think of photography as secondary to sociological research. Photography should be thought of as an illustrative tool to aid external inquiry.

That said, there are a number of photographers who have made honorable efforts to describe for a wider audience much of the significance of prison and gang tattoo cultures.

Araminta de Clermont

After their release from prison, Araminta de Clermont tracked down South African gang members and discovered their stories. Interview with Araminta and her subjects here.

© Araminta de Clermont

Donald Weber

Donald Weber mixed with former prisoners (‘zeks’) in Russia and concentrated on how their prison tattoos relate to their identity and criminal lifestyle. The relationships of these men with female criminals and prostituted women (‘Natashas’) who become their companions feature in Weber’s complex investigation.

“Some rules are simple: you can only get a tattoo while in prison.”

September 1, 2007: Vova, zek. The origins of Russia’s criminal caste lie deep in Russia’s history. Huge territories of Russia were inhabited by prisoners and prison guards. Thieves, or zeks, distinguish themselves from others by tattoos marking their rank in the criminal world: there are different tattoos for homosexuals, thieves, rapists and murderers. © Donald Weber / VII Network.

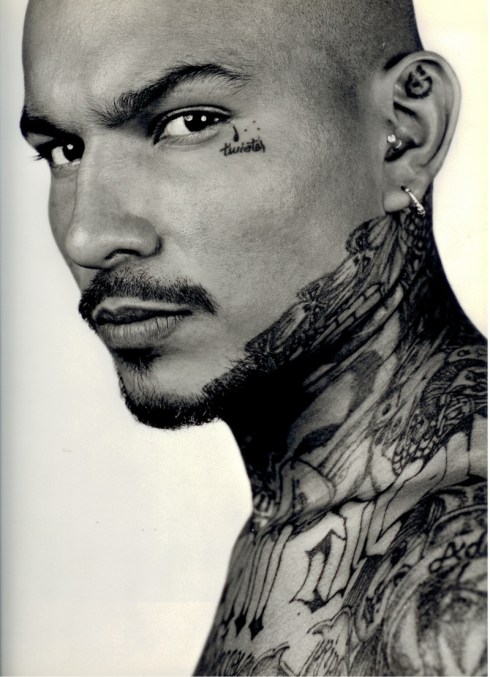

Rodrigo Abd

Rodrigo Abd‘s portraits of Mara gang members in Chimaltenango prison in Guatemala illustrate gang tattoos that are used less and less (from 2007 onwards) due to the unavoidable affiliation and violence they brought the bearer; “After anti-gang laws were approved in Honduras and El Salvador, and a string of killings in Guatemala that were committed by angry neighbors and security forces, gang members have stopped tattooing themselves and have resorted to more subtle, low profile ways of identifying themselves as members of those criminal organizations. Today, gang members with tattooed faces, are either dead, in prison or hiding.”

© Rodrigo Abd / AP

Luis Sinco

In 2005, Luis Sinco of the Los Angeles Times documented Ciudad Barrios Penitentiary in El Salvador, home to 900 gang members, many of whom have been deported from the US. Ciudad Barrios incarcerates only members of the MS-13 gang, which traces its roots to the immigrant neighborhoods west of downtown L.A.

“In the woodshop, inmates made a variety of home furnishings, most of which featured the MS-13 logo. The items sold outside the walls help supplement the prisoners’ meager food rations.”

“It was a of microcosm of L.A.’s worst nightmare transplanted. Claustrophobic, crowded tiers led to darkened, bed-less holding cells and fetid latrines overflowing with human waste.”

Multimedia here.

Moises Saman

In 2007, Moises Saman documented the anti-gang activities of Salvadorian Special Police and the inside of Chalatenango prison, El Salvador. At times Saman’s project focused on the tattoos but is more generally a traditional documentary project. More here and here.

© Moises Saman

Isabel Munoz

Much of Isabel Munoz‘s portraiture deals with markings of the body – what they reveal and conceal. For example, she has previously photographed Ethiopian women and their scarification markings. For her project Maras, Munoz shot sixty portraits in a Salvadorian prison of ex-gang-members. She also photographed the women in these mens’ lives. More here and here.

© Isabel Munoz

Christian Poveda

In El Salvador, Christian Poveda photographed and filmed Mara Salvatrucha (known as MS) and M18, the two Las Maras gangs in open conflict. Poveda wanted to describe their mutual violence and the absence of ideological or religious differences to explain their fight to the death. He described the origins of their war as “lost in the Hispanic barrios of Los Angeles” and as “an indirect effect of globalisation.”

Poveda was shot dead aged 52 as a direct consequence of his journalism. His work from El Salvador was entitled La Vida Loca. Full gallery can be seen here. B-Roll from his work can be seen here.

© Christian Poveda

More Resources

Ann T. Hathaway has collated (disturbing) information and links here about a number of prison tattoo codes.

Russian criminal tattoos have warranted their own encyclopaedia.