You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Louisiana State Penitentiary’ tag.

© Adam Shemper

Photographer: Adam Shemper

Title: ‘In the Wheat Fields, Louisiana State Penitentiary, Angola, Louisiana’

Year: 2000

Print: 9″x9″, B&W on archival paper.

Print PLUS, self-published book, postcard and mixtape – $325 – $BUY NOW

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Another incredibly beautiful and difficult image has been made available for purchase to funders of my Prison Photography on the Road proposed road-trip. This time by photographer and psychotherapist Adam Shemper.

I first discovered Shemper’s work in the Mother Jones feature, Portraits of Invisible Men: A photographer’s year at Angola Prison. Shemper describes how he responded to the frequent question for inmates, “What are you doing here?”

I answered that I’d come to make their largely invisible world visible to the outside. I said I wanted … to reconnect them in a way to a world they had lost. I talked of the prison-industrial complex and the deep-rooted inequalities of the Southern criminal justice system. (Almost 80 percent of the inmates at Angola are African-American and 85 percent of the approximately 5,100 prisoners are serving life sentences.) But as I spoke of injustice, it was obvious I wasn’t telling them anything they didn’t know from their daily lives.

Eventually I stopped trying to explain what I was doing. I simply kept taking pictures.

Chaperoned by a prison official at all times, I visited dormitories, cellblocks, and even the prison hospice. I photographed prisoners laboring in the mattress and broom factories, the license plate plant, the laundry, and in fields of turnips, collard greens and wheat.

BIOGRAPHY

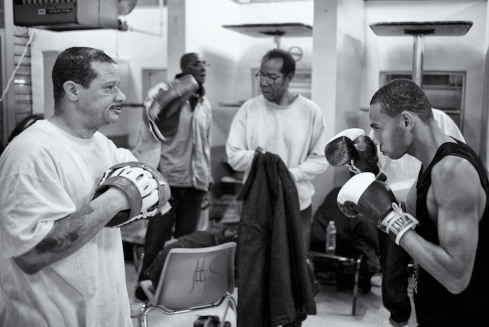

In the management of prisons, fighting is an activity prohibited by the authorities (bar some exceptional instances) and a sign that the regime and control measures are failing. However, at Louisiana State Penitentiary (commonly known as Angola), the Angola Amateur Boxing Association provides equipment and space for prisoners to spar and bout. From the Louisianan Dept. of Corrections website:

“The prison’s boxing program sponsors “fight night,” held every few months with boxing teams from other state prisons competing for corrections department championship belts. The Angola Amateur Boxing Association has held more belts in all weight classes through its 25-year history than any other prison boxing club in the state. The organization is a member of the Louisiana Institutional Boxing Association.”

In February of 2010, Baton-Rouge based photographer Frank McMains went to Louisiana State Penitentiary to document the club, the fighters and a bout. I asked him a few questions about the experience. [Underlining added by me]

How did you hear about the boxing club?

I had heard about prison boxing through another photographer who had attended a bout at a different prison in Louisiana. Oddly enough, he went without his camera. There is also a documentary about a volunteer boxing coach at Angola and I happen to know the guy who put that together. In short, among those who are interested in such things, boxing at Angola and intra-prison boxing between different prisons in Louisiana is somewhat widely known.

Did you do the story on assignment or of your own volition?

These shots were taken because of my interest in Angola and my interest in the boxing specifically. I pitched it to a few national magazines and one picked it up, but the folks at Angola were uncomfortable with the magazine that was interested in running the photos and article. They felt it was not a serious enough venue for the subject, so the photos remained un-published.

How did you gain access?

Angola is surprisingly accessible for a maximum security prison. I can’t say I have tried to get access to any others, but my sense is that they welcome outsiders who want to report on what is going on there. Over the course of several articles about different activities at Angola I have built a relationship with some of the wardens and staff. As a result, I didn’t really have to negotiate for access so much as plan around their schedule. Recent funding cutbacks meant that Angola’s boxing team did not fight teams from other prisons as they had in the past. There just wasn’t the money to transport the prisoners. So, the whole program was kind of in flux for a while, but once they confirmed a date, I wasn’t going to miss it. The staff at Angola are very professional and they are clear about what sort of interactions you can have with inmates as well as what sort of things you can bring into the prison. I have had my gear searched before but the prisoners who are allowed to participate in events like the rodeo or boxing matches are ones the prison administration feels are less of a threat. They basically would not let you into an area with prisoners who they didn’t trust and they also wouldn’t let someone into the prison with a bag full of gear with whom they didn’t feel comfortable.

How many individuals were involved?

There were about eight bouts so that means 16 boxers. However, there were about 150 prisoners who were there to watch the event and cheer on their friends. In the room with us there were probably four guards who sort of came and went as well as a few staff members and the warden with whom I was acquainted.

How did the prisoners talk about the AABA? Had it changed their behaviour or outlook?

One of my real regrets about this project is that I didn’t get a chance to talk to the boxers in more depth. As they were warming up for the fights they were focused on the what was ahead of them and I didn’t want to interfere with that. After the fights were over I spoke with several of the fighters and coaches but it was very informal.

It has been my experience that prisoners are much more interested in talking about where their family might see the photos and things that don’t pertain to their life in prison. Most of the conversations I had after shooting these photos were about people’s families, not about their lives behind bars.

I would like to follow up with the guys involved, but it was sort of outside of the scope of this shoot.

Some people might think boxing is not the right activity for prisoners; that it is violent. What would you say to people with these reservations?

Some people will always object to boxing as a brutal activity whether that is in prison or in Las Vegas. I get that objection, although I see it as graceful and pure in a way that many sports are not, but you can’t deny that it is violent. Last I checked that was a component of the human condition.

When it takes places in a prison I think it is understandable that some people would balk at what could be construed as violence piled on top of violence. It has been my experience that anything that the prisoners get to do is a step towards socializing them and giving them some hope in the face of a pretty bleak future. Angola has an unusual approach to punishment; they try to engage the prisoners in as many activities as possible. The prisoners work the land there to feed the prison population, they maintain the facilities and even staff the prison museum and gift shop. There is also a prisoner run newspaper and radio station. So, if you remove the fact that it is boxing from the equation then I think that an approach to incarceration that does something other than let people rot away in a cell is a good thing; boxing is a commitment to rehabilitation.

The other aspect of life at Angola is that most of the prisoners will die there, simply put. Most are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole. I understand the punishment-as-vengence argument that some might have. It is understandable to look at a murderer and say, “Who cares if they have any dignity.” I think the staff at Angola see a path for redemption for the prisoners that runs through many different courses. It might be boxing, it might be prison ministry. They seem to think that engaging the prisoners is preferable for all concerned to treating them as de-humanized creatures who simply have to be warehoused until the end of their days. From that perspective, Angola seems to run pretty well. Less than a quarter of the inmates are housed in cells and they spend their days working to make the prison run. That, to me, speaks for itself.

Did you get any sense of what the boxers wanted from you as a photographer? Did they want to convey any message to the eventual viewers?

Yes, every time I have photographed at Angola it is pretty clear that the prisoners want to be portrayed as retaining some of their human dignity. Beyond that, they long for connections with the outside world, their family in particular. You can’t forget that the prisoners at Angola have committed horrible crimes, but it is hard to not feel some sympathy for the incredible loneliness and isolation they all seem to share. Maybe they deserve that, it isn’t really for me to say what justice should look like.

How was, and how is Angola? What’s the culture like? How is it perceived?

All of my experiences at Angola have been unsettlingly mundane. In my mind, I expected to see prisoners rattling tin cups on metal bars and walking around in leg-irons or something. But, they are mowing the grass, cooking food, painting buildings, essentially participating in their own, highly-unusual little community. When people think about Angola, if they think about it outside of the rodeo, it seems that they imagine a dreary place of routine horror. I am sure that it is rough out there, very rough in many respects. But, it does not have the feeling of an armed camp where gangs are pitted against each other, where races are seething to tear into one another or where the guards are everywhere searching for escape tunnels. It’s culture will confound your expectations. Or, it did mine anyway. I didn’t grow up with any sense of prison life outside of film and television. If Angola is anything, it is unlike those scenes from popular entertainment. That is not to say it is bucolic or some penal Club Med. It is a sad but necessary place where the passage of time and the intrinsic nature of humanity do not conform to the normal rules.

It seems there have been many photographers who’ve shot at Angola (I might go so far to say it is the most media-present prison in America). Would you agree? What would one attribute that to?

In a word, yes. It is a thoroughly media documented prison. I think that is for two reasons. First, it is highly unusual in its approach to incarceration as I have spelled about above. They just do things differently there in terms of engaging prisoners rather than just warehousing them.

Secondly, it seems that the administration at Angola, starting with warden Burl Cain and running all the way down, are genuinely empathetic to the prisoners. They know that some of them have been changed, and perhaps redeemed, by the way Angola does things and they want people to know about it. I think they are also keenly aware of how the lack of hope not only destroys the human spirit but also makes prisoners much more difficult to handle. If the prisoners have a reason to get up in the morning then they see a value in toeing the redemptive line that Angola is pushing.

The staff know it is expensive and pointless to incarcerate grey-haired old men who are no longer a threat to society. It seems that Angola is trying to re-humanize prisoners in the eyes of the general public in an effort to change the way our legal system approaches punishment and justice.

Thanks Frank.

Thanks Pete.

_________________________________________________________

Frank McMains is a jack of many trades. He’s got a lot of Flickr. I thank Frank for his time to share his work and thoughts. You can read more about Frank’s time photographing at Angola at his own website Lemons and Beans.

Angola prison rodeo © Sarah Stolfa

Philadelphia based photographer Sarah Stolfa, best known for The Regulars, a portrait series of punters at the bar she tended, has posted some new work on her website.

Pallbearers struggling with a casket, an elegantly dressed African-American lady with a gun holster, a man with a singed blanket stood in a charred field, a long-limbed man with leather bible, public urination, public housing; this is a visually uneasy but coherent edit and presumably the result of a road trip.

Also included are two photographs from the prison rodeo at Louisiana State Penitentiary (one and two). I am uncovering more and more photo projects from this particular event and I’m still working out what, if anything, this relatively high level of exposure means within the specialist sub-sub-genre of prison photography.

Damon Winter emailed me this week to let me know he’s been tinkering with his website. Since we spoke last [here and here] about his ‘Angola Prison Rodeo’ series, he’s revisited and re-edited.

http://www.damonwinter.com/ > STORIES2 > 5 > ANGOLA PRISON RODEO

The image above is new and one of Damon’s preferred images.

Also since then, Winter covered Haiti. It was his first work in a disaster area. This week, Winter’s Afghanistan i-Phone images hit the front page of the New York Times – Between Firefights, Jokes, Sweat and Tedium (James Dao, November 21, 2010)

On those i-Phone Hipstamatic App shots … three things.

1) David Guttenfelder did the same thing earlier this year with a Polaroid App.

2) The simple i-Phone angle is not a story. Judging by the cursory Lens Blog entry, I think James Estrin and Winter might have known this.

3) I’ll pass on the i-Phone photos. Mainly because these have got a stupid amount of attention; attention that should be going to Winter’s videography and incredible number of stories in his short time in Afghanistan.

Damon, I still love your portraits and I still dig your work!

ELSEWHERES

I’d also like to recommend my interview with Winter (for Too Much Chocolate) about his career trajectory.

Brixton Prison governor Paul McDowell: 'We don't let them have too much fun.' Photograph: Martin Argles

THE FACTS

The UK’s most well-known prison radio station is the Sony Award winning Electric Radio Brixton. It has come in for high praise.

The US’s boasts KLSP which broadcasts within Louisiana State Penitentiary, the prison commonly known as Angola. Andy Levin of 100Eyes photographed this New York Times coverage.

THE MISSIONS

In both cases, the radio stations serve to provide inmates with valuable, marketable skills AND to disseminate prison specific communications.

Electric Radio Brixton is the model for fifteen other prison radio stations up and down the UK. The Prison Radio Association is currently working with over 40 prisons and hopes eventually to build a national network for the benefit of all British prisoners. It is a community action.

Unlike Brixton’s radio initiative, the scope and model of KLSP is not intended to go national. KLSP was established in 1986 as a “means of communicating with everyone in the prison at once. Angola is the country’s largest correctional facility, with 5,108 inmates, so the need to disseminate information rapidly is critical.” The KLSP station at Angola is the only FCC-licensed radio station in the US facilitated by prisoners.

Sirvoris Sutton is a D.J. known on air as Shaq at KLSP-FM, the Louisiana State Penitentiary station where gospel wins out over gangsta rap. © Andy Levin/Contact Press Images, for The New York Times.

As with any enterprise at Angola, the radio station is implicated in Burls Cain’s philosophy of religious and moral rehabilitation. Warden Cain encourages all religious and spiritual practices, but inevitably most of Angola’s religious alliances and support are Christian:

KLSP is licensed as a religious/educational station, and, through Cain’s efforts, has formed a close alliance with Christian radio. Until recently, the station was using hand-me-down equipment courtesy of Jimmy Swaggart; last year, His Radio – Swaggart’s Greenville, S.C.-based network of stations – ‘held an on-air fundraiser for the prison, broadcast live from Angola. They quickly surpassed their $80,000 goal, raising over $120,000 within hours.

Cain used the money to update the station’s flagging equipment and train inmate DJs in using the new electronic system. In the months following their initial partnership, Cain deepened his relationship with Christian radio stations. KLSP now carries programs from His Radio and the Moody Ministry Broadcasting Network (MBN) for part of the day.

With regard the station and its remit, Brixton Prison Governor, Paul McDowell does not have the same influence as Cain. For one, the radio is operated by an independent charity, and two, the prison culture in Britain is not dictated by the personal cult/philosophies of the warden as in the US.

McDowell sees the radio station as a good way to develop critical and positive thought.

McDowell’s main work is to keep infamous inmates away from the airwaves and avoid unnecessary (sensationalised) criticism of the project;

I am a prison governor and half of my life is spent managing the politics of prisoners. One of the things I am not going to do is put Ian Huntley on a radio station to deliver a programme every week. That is opening us up [to attack] and if we get criticised for that then we might end up losing the whole thing.

I’d be dismayed if people in the UK could not see Electric Radio Brixton as a wellrun and sophisticated engagement of prisoners’ minds. I have personal reservations about the Christian focus at KLSP, but this focus has been the norm throughout Angola for 15 years.

Both of these enterprises deserve praise. Next, the content broadcast on their airwaves requires scrutiny.

Too Much Chocolate

When Jake Stangel put out a call to interview Damon Winter for Too Much Chocolate I didn’t hesitate. How often do you get to bend the ear of a Pulitzer Prize winning photographer?

Jake assured me that Damon was – is – “a super-nice guy” as well. I might argue that Damon is too nice; he carried, without complaint, a sinus-busting cold to deliver the interview.

Damon and I spoke about his assignments in Dallas, L.A. and New York, the Obama campaign coverage, making portraits, Dan Winters, Irving Penn and Bruce Gilden. Read the full interview here.

_____________________________________________________________

Angola Rodeo

Not without my own agenda, I also asked Damon about his experience down at the Angola Prison Rodeo:

PP: Why were you there?

DW: I had gone out for two trips. It was when I worked at the Dallas Morning News. The way I pitched it was that the prison was expanding the program to launch a spring rodeo. I wanted any excuse I could get to go down there and photograph. It sounded absolutely incredible.

DW: And the paper ended up not being that interested. They may have run a small little blurb about it, but I did it for my own interest. It was fascinating – a completely wild situation. Most of these guys came from the cities. Some had never even seen a cow let alone roped a horse.

PP: Describe the atmosphere.

DW: The closest thing to modern day gladiators – something you’d see in a Roman Coliseum. The crowd is chanting for blood, they want to see a violent spectacle where prison inmates are the subjects. It’s the same reason people go to see a horror movie or stare at a wreck on the highway. It is a very strange situation but they want to see blood.

PP: Do you think it helpful to the local community?

DW: There is no interaction between public and inmates. The public is there to observe and the inmates are there to entertain. The benefit the inmates gain is at a level very specific to their situation. They risk injury being in the ring with massive bulls, and their prize is something I think anyone in the free world would laugh at, you know? Maybe a couple hundred bucks. But it is substantial in their environment.

It speaks to the bleak situation that those guys are in that this would be enticing – to risk bodily harm for a couple of hundred dollars.

I don’t know how constructive it is for relations between prison and non-prison populations.

PP: Which is unusual because in any other state across the country, there is no interaction between the public and the incarcerated population.

DW: What’s your feeling?

PP: I think it builds a division at a local level, but it also feeds a national view that excludes the realities of prisons. The inmates are put out there to be observed, photographed and consumed. Such a presentation is not unpalatable to the American public. To the contrary, the public feels as though it gains from it. I think here unexamined (and abusive) interactions can be confused with relationships.

I think the wasteful and very boring reality of prisons in America is not going to make it into newspapers or media, but the rodeo does. It skews perception. I think the rodeo is problematic.

DW: I felt the event was dehumanizing. It was done in a manner so that the inmates are reduced to the level of the beasts they are competing against. It seems the field has been leveled between animals and inmates and the feeling that you get from that is that they themselves are like animals. They are not seen terribly differently from the way that the animals are seen.

PP: I am not sure that that sort of spectacle would take place outside of Louisiana, certainly outside the South. Granted, Angola’s warden Burl Cain jumps at the chance to get the cameras in at any opportunity.

DW: Yes, I saw The Farm, a documentary filmed at Angola.

PP: I think Cain’s administration paired with the history of the event creates a spectacle at the rodeo that goes unexamined.

PP: Cameras are common at Angola; documentary shorts on the football team and photo essays on the hospice. It is a complex that has 92% of its population.

DW: You should look at Mona Reeder’s work. She works at the Dallas Morning News. I think it was called The Bottom Line and she turned the stats into photo essays and one of the stats was the number of prisoners in juvenile facilities. She got some pretty good access. She received a R.F. Kennedy Award.

PP: I certainly will. Thanks Damon.

DW: Thank you.

_____________________________________________________________

Below are three of Damon’s photographs from Afghanistan which stopped me in my tracks. Unfortunately, I discovered them after the interview so didn’t get Damon’s take on them.

The images of the boys really affected me. We see so many images of bearded men, U.S. Marines in the dirt, explosions, women in burqas, etc, but it is the children of Afghanistan who will carry the violent legacy for the longest. What pictures reflect that fact?

It is an impossible task of any image to near ‘truth’ or reality, but these two pictures get very close to the sad reality of conflict and the impressionability of youth.

Yes folks, a US prison runs a rodeo for the entertainment of the public (from Louisiana and beyond). Believe it.

I have only ever discussed this event in terms of is dicey ethics, but being a weak-spined liberal never gone full-throtle in condemning it as exploitation. Matt Kelley and I were both agreed that we couldn’t fully judge the spectacle without having been ourselves or talked directly with participants.

I met Tim McKulka, one of many photographers to have shot at Angola, and asked for his impression.

The rodeo of course exploits the prisoners. It is gladiatorial . It is taking people without the skills to ride a bull and putting them on a bull for peoples’ entertainment. For the prisoners themselves, it gives them the opportunity to be a normal person a couple of weekends in the year. It is an opportunity to make some money, to see their family, to earn a belt … so what have they got to lose?

Do you think any of them are taking part precisely because they are on life sentences?

I don’t know what the percentage of the participants is in terms of lifers. I know in the prison itself has about 92% [of offenders on life sentences] Some of them for some absurdly minor crimes – a third offense or an unarmed robbery. But I don’t know. What I do know is that – from the prisoners I talked to – it’s a voluntary program and no-one is forced to do it.

They are being exploited but that prison in particular is the only prison in America that turns a profit so it is an exploitative institution anyway.

McKulka has since moved far away from the cultural mores of the American South. He has crossed an ocean and continent but continues documenting the politics of race and identity.

Tim McKulka started shooting for Edipresse Publications in 2003. With Jean-Cosme Delaloye, he covered diverse feature stories such as the crisis in Haiti in 2006, the Angola Prison Rodeo, the US presidential elections in 2004, illegal immigration into the US and New Orleans in the aftermath of Katrina. In 2005, he covered the presidential elections in Liberia. In 2006, Tim started with Jean-Cosme this project of a news agency. He later joined the UN as a photographer in the fall 2006. He is now based in Juba, in Southern Sudan.

Troy West, Angola Inmate

Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate per capita of all US states. over 1,100 per 100,000 – that’s more than 1 in a 100. Angola (Louisiana State Penitentiary) is the mother of all prisons, carrying a weighty reputation and weightier history.

Only Georgia has a rate above 1 in a 100, as Louisiana does. The other Southern states make up the top five (Texas, Alabama and Mississippi).

These stats are due in most the more frequent sentencing of men to life without parole. The disproportionately high rate of prisoners who die within Southern prisons as compared to other state institutions makes for a very different culture.

Many photographers including Damon Winter and Lori Waselchuk have focused on the unique aspects of Angola culture. The rodeo is well known, the hospice less so, but least well known may be the football league.

I have noted before the value of sports in prison, and Angola Prison Football a film-short by Charlie Gruet supports my position.

In it, Angola warden Burl Cain states his philosophy, “Good food, good medicine, good play and good pray. Lose any of those elements and you’ll have violence in your prison, but you would in your home. You think about it.”

The inmates back up the third point. It’s a well done documentary and to think that over 70% of the men in the film won’t ever get out just blows my mind. (Source: 2008 LSP Report).

Watch closely from 4.03 onward.