You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Louisiana’ tag.

I’ve said before that Angola prison is probably the most photographed prison in the nation. Damon Winter, Bettina Hansen, Darryl Richardson, Tim McKukla, Sarah Stolfa, Adam Shemper, Lori Waselchuk, Deborah Luster, Serge Levy, Frank McMains and thousands more. Even I’ve had a go!

Well, now add Giles Clarke to that list . He was down there at the end of 2013. A small edit of the pictures then appeared in Vice.

This is the second in an ongoing occasional series I have going with Clarke in which we chat about the whys and hows he’s going to prisons … which he is doing more frequently these days.

Remember, while all this palaver occurs in public-accessed areas, Albert Woodfox — the single member of the Angola 3 still incarcerated — awaits potential release on bail and a third trial. All this, in spite of the State of Louisiana’s case against him being largely discredited. As we’ll learn from Clarke, Louisiana has a strange definition of justice.

All images: Giles Clarke/Getty Images Reportage.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Prison Photography (PP): Why were you in Louisiana?

Giles Clarke (GC): I originally went down to the area to explore the toxic industrial corridor that runs from Baton Rouge south, along the banks of the Mississippi River, to New Orleans. The area is otherwise known as “Cancer Alley.” While researching that horrible story, I read in a local paper that Angola Prison would be holding its Prison Rodeo. It seemed like a good thing to do on a Sunday in the Deep South.

PP: Now, c’mon Giles, everybody and his mother has photographed the Angola Prison Rodeo. Why did you want to shoot it?

GC: A couple of years ago, I had made a short commercial film for ‘SuperDuty’ Ford Trucks, which featured about ten 1800lb bulls and some rather small Midwestern bull-riders. Seeing those bulls REALLY close-up left a deep impression. The guys who rode them were pros but they often got hurt. When I read the ad for the Angola Prison Rodeo, my thought was ‘How the hell are a load of prisoners going to deal with these huge animals?’ and secondly, ‘Why the hell are the prison letting them do it?’

Then, of course, there is the legacy of Angola. It just so happened that Herman Wallace — one of the Angola 3 — had died only 2 weeks before the rodeo. I attended his funeral in New Orleans which was held the day before the rodeo. It was a very moving occasion. If you know the story of Herman Wallace, then chances are you want ask some questions — which is what I did when I got into Angola the very next day.

PP: Was there anything specifically different you wanted to do at the Rodeo, or Angola generally? What did you want to achieve with your photographs?

GC: Most of the prison media officials were about as unhelpful as they could be. Yes, they were courteous and let me talk to the prisoners before, but when it came to the actual event, they kept us well away from the arena. We photographers were penned high-up in the nosebleed seats. Almost the whole rest of the audience was closer. It was blindingly obvious that they didn’t want to show the reality and the gore.

Whenever we asked about injuries we were fobbed off. That was a shame. Fact is, it’s brutal and it’s not pretty when things go wrong. Which they do a lot.

PP: The Angola Prison Rodeo looks pretty gladiatorial, but I’ve heard arguments to say it’s good for the prisoners — prize money, selling arts, meeting friends and family, glory and honor. What is your reading of the event?

GC: I was really skeptical to begin with but having talked to many of the prisoners who were involved in the event, I soon realized that this event was something that they really looked forward to. There was plenty of money at stake. If you pluck the puck from the bull’s nose, you win $500! Thats a lot of cash on the inside. Of course, the glory. If you win the rodeo you get to wear ‘Angola Prison Rodeo’ belt buckle.

At the end of the day, its a big money-making exercise that involves the prisoners. They make the products, sell the tickets for rodeo and take home about 10% of those earnings. The warden says this money goes back into rehab programs. If that’s really the case, then its a good thing.

PP: Who were weirder? The prisoners, the staff or the public?

GC: It’s hard to focus that question. I’m from the UK and to be honest, I find all this stuff fucking weird! I find the entire Louisiana justice system almost laughable … except for many its far from laughable. In Angola, there are over 5,000 men are held for life with no chance of parole — they’ll never ever leave. They talk about rehabilitation, but for what? So you don’t get sent to the punishment wing for your entire life? It’s all so messed up but they seem to think they are on the right path.

You gotta remember also that 2,000 staff family members live on the grounds of Angola. It’s work that is welcomed and promoted. Incarceration for many is a profitable business that needs to be continually fed. It’s an ugly beast whichever you look at it. Guess it’s better that Angola 40 years ago, when conditions were mostly described as squalid and medieval.

PP: When you spend time in Louisiana, does Angola Prison start to make sense?

GC: Well, as much as any prison can make sense. Mass-murderers and serial killers need to be locked and probably sent down for the rest of their lives, but in the USA, and especially in Louisiana, they want to lock you up as soon as they legally can often for crimes that do not comprehensibly meet the sentence.

I am very cynical toward the American justice system. It can work for you, if you have the money. Most don’t, so down they go for, usually for as long as they can *legally* send you down. Clearly, it’s better if you ain’t black. The prison business is big bucks for so many that it’s now sadly an accepted part of American society. For Angola, its a dead end. It’s depressing and fucked up. What else can I say?

PP: And so does the rodeo make sense?

GC: The rodeo was actually thought up by Jack Favor, a man who was framed for two murders and wrongly convicted for life in Angola. He was eventually released in 1974. As a former rodeo rider himself, he is the man who instilled the original self-discipline mantra into rodeo riders in Angola when it opened to the public in 1967. The whole idea came from a wrongly convicted prisoner. That was interesting to me. For the prisoners here now, it is an honour to be picked for the twice annual rodeo. And a chance to gain some self-worth and respect … and cash.

PP: Tell us about your relationships with the prison administrators.

GC: I don’t have a lot to say about them, other than they have unions, want full jails and probably don’t really give a fuck about most of the people they oversee.

They have families and need a job. I’m sure they are decent enough people but I can’t imagine that it’s much about helping people. I’m not sure one grows up saying “You know what, one day I want to work in a prison.” Maybe some do? Either way, the prison industry, like the military, is pretty much one big lie that we all tow along with. “It’s for the sake of safety and security.” Bollocks. It’s big business full stop.

PP: Did you meet Warden Burl Cain?

GC: I did. And I liked him. I found him refreshing and honest.

PP: He’s a bit of a media-celeb at this point and he divides opinion.

GC: While other journalists at the event asked him fairly straightforward rodeo related questions, we asked him some pretty tough things in regard to conditions, the Angola 3 and Herman Wallace. Cain answered them all directly.

Cain can be credited for turning Angola into the place of relative calm that it appears to be today. That had to happen. The dark legacy of Angola was something he wanted to wash away. His rehabilitation programs which give the prisoners work and more importantly, self worth, cannot be underestimated in prison reform. In many ways, he’s just the gatekeeper. He has to keep a clean and busy prison. I was impressed by him and hope others might model prisons after him. It was Burl that made sure that I was allowed back into the facility the next day for a private tour. It would not have happened without him. I thank him for that.

PP: Did you meet memorable prisoners, who said things to you that you maybe cannot say in your pictures?

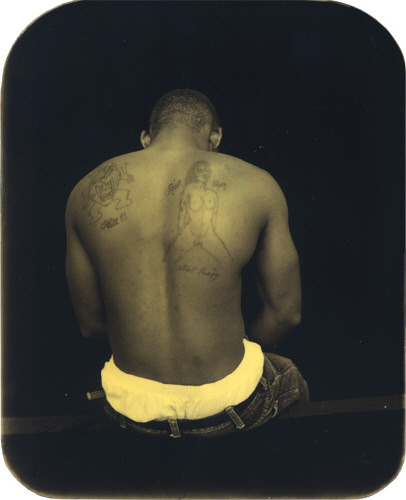

GC: I met Bryce, (above) prisoner #582440, both at the rodeo and the following day inside his jail wing. At 26-years-old and serving life with no chance of parole, Bryce had been at Angola for 3 years, and said it’s the best prison he’s been in. He was locked up for second-degree murder, but is trying to fight the charges.

“It was a bar-fight, someone threatened my brother, I pulled a gun, it dropped and fired. That stray bullet killed a man,” he said.

The original charge was manslaughter, but, as Bryce said, “This is Louisiana.” I asked Bryce how he survives knowing he’ll never return to the outside world.

“How do I keep going? It’s all about respect in here. As long as I respect the next man and don’t show weakness then it’s all fine. The rodeo is something I look forward to all year so I behave ‘cause this is a real privilege.”

PP: What do you want folks to take away from your Angola photos?

GC: Why do we have 5% of the worlds population but 25% of the world’s prisoner population? Are we really doing this right?

In the eyes of those who run the current incarceration system, things are going just fine. But with the decriminalizing of certain low-level drug offenders and minor repeat offenders, one must assume that the authorities are also nervous about keeping these ridiculous occupancy levels so high. Private prisons are a huge worry. As are the new immigration centers that are bursting at the seams. From the outside, the U.S. seems to encourage mass-incarceration and most members of the public are still sort of okay with that. It’s fucked up.

One hopes that pictures can affect change but the reality is that no-one in authority really wants to affect change or be the focus. Many like it all the way it is — it keeps the dollars coming in after all.

PP: Thanks Giles. Until our next collaboration …

GC: Thank you, Pete.

All images: Giles Clarke/Getty Images Reportage.

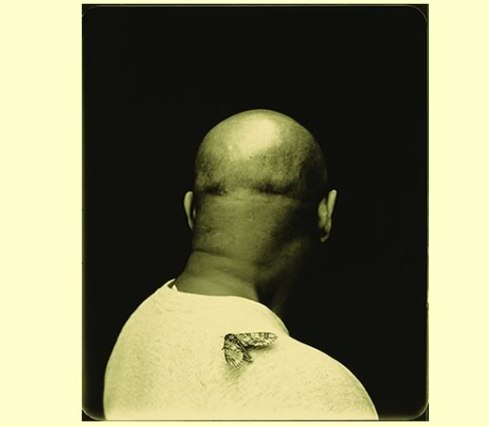

Between 2002 and 2003, New York based photographer Serge J-F. Levy, visited six maximum security prisons across multiple states. The series is called Religion in Prisons.

I am decidedly ambivalent about the role of religion within prisons – it can be a force for good and for positive change, but it can also be reductive in scope and used for manipulation. I wanted to ask Serge a few questions to see if he could help me, and us, through some of the issues and interactions religions bring about in prison environments.

Q&A

Prison Photography: Tell us about your approach.

Serge J-F. Levy: When I did the project, I did my best to approach each individual (inmate) tabula rasa. I did everything within my power to try and understand who they were in the moment I met them and to understand who they wanted to be from that moment onward. In most cases I did not know what each person was punished for.

Though I feel a general compassion for humanity and a desire to understand troubled people, I also understand that the acts of many of the people I photographed often had dire and unimaginable consequences on the lives of their victims and the victim’s families. So, my compassion and understanding is measured with an awareness of the distinct nature of my relationship to my subjects.

It seems like you’ve been to a few states. Which prisons have you photographed in and in what time period?

I started in Greenhaven Maximum Security in New York State. I went on to photograph at the Muncy Women’s Unit in Pennsylvania, MCF (Minnesota Correctional Facility) – Stillwater, MCF-Oak Park Heights Super Maximum, MCF- St. Cloud, and Angola in Louisiana.

What attracted you to prisons and specifically religion in prisons?

When an accused criminal is locked away, we, as a country and a society, have assumed the inmate will be experiencing some degree of “rehabilitation.” Instead, it would appear these environments quite often breed further damage, dysfunction, and pathology. I became interested in how inmates used their time to pursue a form of healing outside of the prescribed forms of daily routine. Through religious communities, inmates were often seeking a form of spiritual rehabilitation. This spiritual rehabilitation often provided the inmates a way to metaphorically experience a freedom beyond the obvious confinement and constraint they experience in their present lives. Religion also provides many adherents a lasting form of reflection and cleansing to purge the remains of unresolved tragedy from their pasts. So you asked why I was attracted to this project? Because I feel the literal experience of being imprisoned, stripped of freedom, and confined in a den of thieves (and murderers, etc.), is a powerful figurative example of aspects of the more general human experience. The ability to find a way to transcend the reality of one’s current circumstances and experience a healing and freedom through the channels of spirituality and reflection… that’s a valuable tool.

How did you negotiate access? Did different DOCs react to your request differently?

I got access through the most classic technique I know of; I met someone in the mailroom who introduced me to someone who worked on the second floor who introduced me to the fourth floor and on up the chain until I had an endorsement to enter my first prison. After working in Greenhaven Maximum Security Prison for several visits, I had created a body of work that would encourage future prisons of the valuable intentions and ideas behind my work.

And related to the last question of how I got access, the work I was doing was not much of a security risk for prison administrations as I was mostly working in areas and in ways that could only make the prison system and its staff look good. However, I guess there was always the risk that I could have turned my camera in a different direction and as was the case in many instances, I was left alone with inmates long enough that I could have seen more than I was potentially supposed to. But that’s not who I am or how I work.

Any memorable interactions?

One warden in Texas suggested we grab tea and beer when I made it down. I never made it down but I was always interested in whether that was an obscure Texan custom.

Is photography a security risk for prison administrations?

I just don’t know the nuances of security well enough to weigh in on that question. I could imagine that with a particular intention, a photographer may be able to provide the necessary coverage to develop a plan, but I am mostly constructing this from my avid movie watching hobby!

Some of the services/prayer/rituals you’ve photographed seem quite involved. How much time did prisoners spend involved in religious observance? Were their other outlets available to them for self-reflection and improvement, e.g. sports, industries, education, group counseling, libraries?

I found it interesting how religion served multi-faceted functions for the inmates. On the most direct level, it was a form of spiritual cleansing and growth that would happen in services and weekly or daily gatherings and meetings in chapels and make-shift religious venues. But beyond these formal locations, religion becomes an identity and an opportunity to develop a social circle; a comparison to how gangs function in prison might be an apt comparison because as I understand it, competing religions would at times seek to sabotage the work of each other. One such case was how the baptism tank had to be replaced by a laundry cart because it would constantly develop mysterious holes at Stillwater Maximum Security Prison in Minnesota.

But religion was also practiced in the art inmates created; from sculptural effigies to paintings and drawings of religious scenes, the hobby shops and prison cells often contained quite a bit of religious memorabilia. There were several outlets for inmates to reflect and experience spirituality; the arts, group meetings of various sorts (including therapy), formal religious gatherings, one-on-one consultations with chaplains, and library hours.

Policies varied from prison to prison and in each case I would hear inmates express grievance as to the limitations that were imposed upon them. I was only there for small slices of time and generally wasn’t able to get a more holistic sense of what the greater experience was like.

What did the prisoners think of your presence?

I think the inmates respected the integrity of my stated goals and the ideas I had for my work. I also think, rightfully so, many inmates were skeptical as to my intentions and my affiliation with the media. After all, many of the people I worked with were directly featured and often intensely maligned in the media during their prosecution and processing through the judicial system.

What did the correctional officers think of your presence?

The correctional officers, were largely very helpful but also insistent upon reminding me of the omnipresent dangers. On more than one occasion I was told that a particular inmate was trying to con me into believing one story or another. I generally felt that the correctional officers had seen or heard quite a bit during their time working inside.

Were their any days and/or experiences with the prisoners that shocked, surprised or delighted you?

Kneeling in a small room for Friday Jumma with 300 Muslim inmates listening to and responding to the call of Allah Oh Akbar is something that can’t be explained but only felt. Same for a Baptist or Pentecostal service.

On one occasion, I sat in a room of 10 women gathered with a Catholic chaplain, and listened to one woman recount her experience of being raped and simultaneously attacked by a dog. Sometimes, it was more important for me to listen, feel and internalize the moment without the filter of photography.

Do you follow a creed or religion?

I don’t follow any particular religious path. I lead a life that is guided by principles that I have culled from religious practice and ideas that have resonated with me over time. My “religion” is constantly evolving. The sources behind my spirituality that I can identify are Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and many other faiths and disciplines I have encountered throughout my life.

What has been the reception to these images?

I think people like it. But due to the limited exposure these images have had, I have yet to hear strong dissenting opinions if there are any.

How do you think your images fit into the visual landscape of prisons and prisoners in America. Do they confirm or counter stereotypes or common narratives?

I am seeking to provide a record of the people practicing religion in prison. Of the work I have seen done in prisons, much of it addresses religion as a component of life inside, and therefore seems to be geared toward molding the religious component of prison life into a greater aesthetic and narrative whole.

My work is more thorough in exploring this particular [religious] angle of prison life. Of course, I could be very wrong about the full breadth of quality work done on this specific topic.

Thank you for your time Serge.

BIOGRAPHY

Serge J-F. Levy’s work is represented by Gallery 339 in Philadelphia and has been exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Schroeder Romero Gallery in Chelsea, and The Leica Gallery (New York City and Tokyo) among many other national and international solo and group exhibitions. In 2011 the Princeton University Press published a book of Serge’s photographs made during his yearlong photography fellowship at the Institute, along with essays by Institute members. Serge’s magazine photography has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Life, ESPN The Magazine, and Harper’s Magazine among others.. For over 10 years Serge has been on the faculty at the International Center of Photography in New York City where he is a seminar leader in the documentary/photojournalism program and teaches street photography, editing, portraiture, and several other courses. In addition to his street photography practice, he is an avid draftsman and painter. Serge lived in New York City for his whole life … until recently moving to the Sonoran Desert.

MORE ON RELIGION ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

Body vs. Structure: Islam in Prisons

Dustin Franz’s ‘Finding Faith’

Andrew Kaufman and the Incarcerated “Jesus Freaks”

Photog Searches for Healing on Texas’ Deathrow

David, DJ at the prison radio station holds a Polaroid of him and his wife. He said the picture was taken more than 15 years before, when he was 18 and she was 16 years old. During his hour as DJ he played mostly Gospel and Christian music at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, June 27, 2000.

Photographer, writer and psychotherapist Adam Shemper and I talk about his portraits and photographs from Louisiana State Penitentiary.

LISTEN TO OUR DISCUSSION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE.

At the age of 24, Adam was challenged (almost dared) by a family friend to “experience something real.” The friend offered him an introduction to warden Burl Cain and the test to photograph within Angola Prison.

We all have difficulty putting our work out in the world, and Adam found that after his nine-month stint at Angola he had more questions than answers.

For many years the work remained unpublished and Adam’s own justifications for the work unsteady. We discuss the life-cycle of the photographs, the reactions of the prisoners to Shemper and his work, and generally, the responsibilities of photographers toward their subjects.

In photography, as in life, it is all about relationships and positive connections that benefit all parties.

Victor Jackson, cell block A, upper right, cell #4. He had ‘I Love U Mom,’ tattooed on the inside of his right forearm. Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000.

LaTroy Clark, cell block A, upper left, cell #6, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Don Jordan reads the Bible in his cell, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Jonathan Ennis puts a puzzle together of a farm scene in Ward 2 of the Louisiana State Penitentiary hospice at Angola, March 21, 2000.

A man sleeping during the day in the main prison complex, camp F dormitory, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, February 1, 2000.

Henry Kimball and Terry Mays in cell block A, upper right section, cell #15, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, September 6, 2000.

Brian Citrey, main prison, cell block A, upper right, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Nolan, a prison trustee, standing in front of the lake, where he often spends his days fishing. He caught catfish and shad on this day for the warden and his guests. Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, June 27, 2000.

Man cuts open sacks of vegetables to sort through, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, June 27, 2000

After chopping weeds in the fields, men wash up as they transition back to their cell blocks at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000.

Men housed at prison camp C dig a ditch at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, January 31, 2000.

All images © Adam Shemper.

Images may not be reproduced elsewhere on the web or in print without sole permission of the photographer, Adam Shemper.

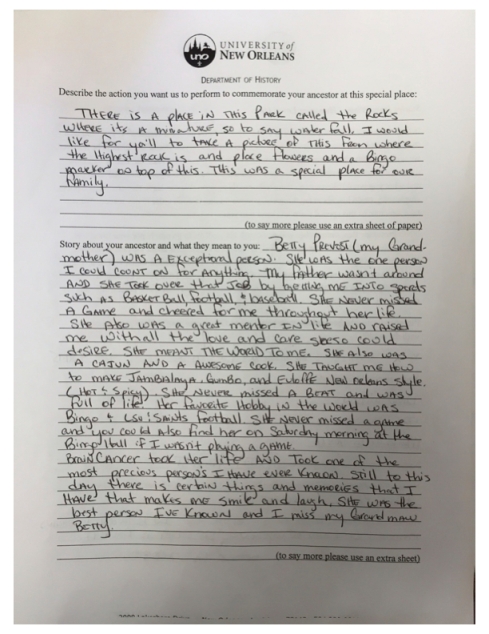

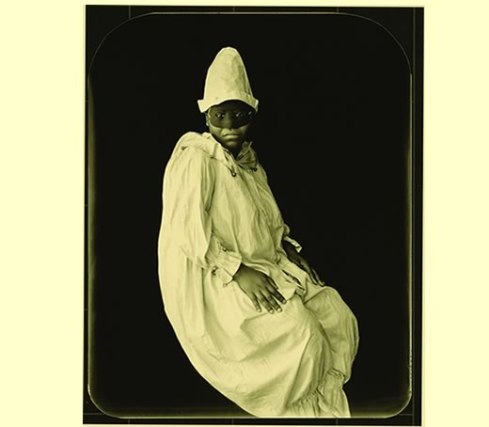

ONE BIG SELF

I have told many people in person that Deborah Luster’s One Big Self is the most impressive prison photography endeavour to date. I have been slow to state as such on this forum because the scope, details and inspiration of the project are so overwhelming.

Every portrait deserves an essay, but that obviously is not possible. Rather than delay any further, my aim here is to present many of Luster’s portraits, describe the bare facts, and provide some further resources to understand the work.

THE FACTS

Completed between 1998 and 2003.

Portraits taken in many different prisons – mens and womens facilities; minimum to maximum security throughout Louisiana; and with different levels of supervision.

Tens of thousands of portraits taken.

Luster estimates she gave away 25,000 portraits to prisoners over the course of the project.

Luster worked fast – 10 to 15 portraits per hour. At a point working in sheer volume became the only reasonable way to respond to the size of the prison population with which she was engaged.

BACKSTORY

Luster got involved in this longitudinal study through a chance request. Luster’s emotional standing at the time of beginning was – is – atypical and unexpected.

Luster’s mother was murdered in 1988; “Although I was interested in photography prior to that time, I didn’t study or practice it. I began photographing in response to her murder.”

Luster did not deliberately go in search of the subject. In 1998, she was driving near Lake Providence, Louisiana when she came upon East Carroll State Prison Farm. She literally knocked on the front gate. There and then Warden Dixon gave her sanction to begin the endeavour.

VIDEO & AUDIO

SFMoMA has done us a great service in recording and publishing the following video shorts.

In four videos, Luster describes the ORIGINS of the project, elements of ACCIDENTAL PERFORMANCE, printing on ALUMINIUM PLATES, and comments on INDIVIDUAL WORKS.

Remarkable tales.

RESOURCES

Deborah Luster is represented by Catherine Edelman Gallery, who present the best online selection of her portraits.

Good background information is provided by Doug McCash of the New Orleans Times Picayune; David Winton Bell Gallery at Brown; and Grace Glueck of the New York Times.

In 2000, One Big Self was exhibited at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, providing an overview and gallery of the project.

INTERVIEW

The best in-print interview with Luster is included in recent publication, PRISON/CULTURE (City Lights), which I reviewed two months ago.

THE BOOK: ONE BIG SELF

The book is at a premium now and you’ll struggle to find it for under a $100. It is published by Twin Palm Press.

IMAGE/WORDS

Luster collaborated with writer/poet C.D. Wright. Luster’s images and Wright’s poetry are a great complement to one another. Listen to Wright read her poetry from the project.

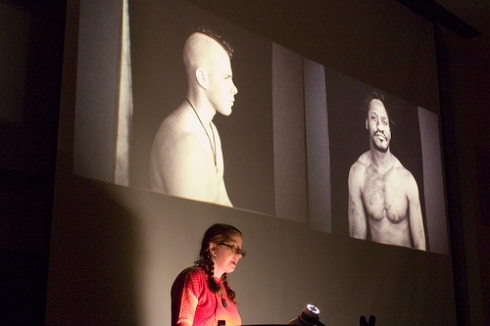

A PROJECT ONGOING

Despite the passage of seven years since the projects official closure, Luster’s career continues to be defined by her ground-breaking, genre-defining project. Her lectures are vital in that she describes the many facets of the project – from security arrangements, to gear (she generally worked with digital), to processing (she made use of tintype imitation technique printing onto small metal sheets), to the specifics of exhibition.

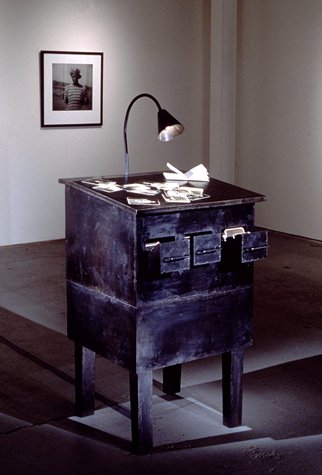

The image below shows a steel cabinet and lamp (containing 288 silver-emulsion aluminum plates) as it was displayed at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and other institutions. Luster wanted to create a tangible viewing experience in which the audience were required to handle the archive of human life in the same way the state of Louisiana organised and disciplined the bodies under its supervision.

In the video (below) Luster talks us through the senses and noises of the exhibit design.

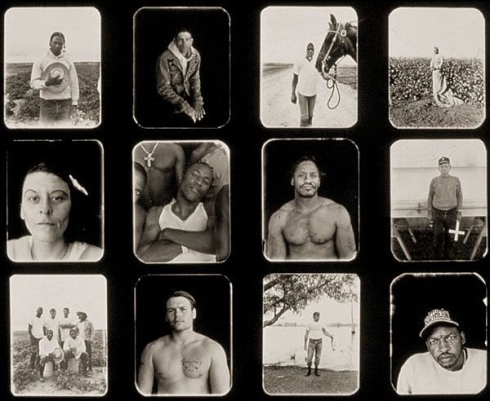

Time is of the essence today, so why not a quick look at a mugshot archive?

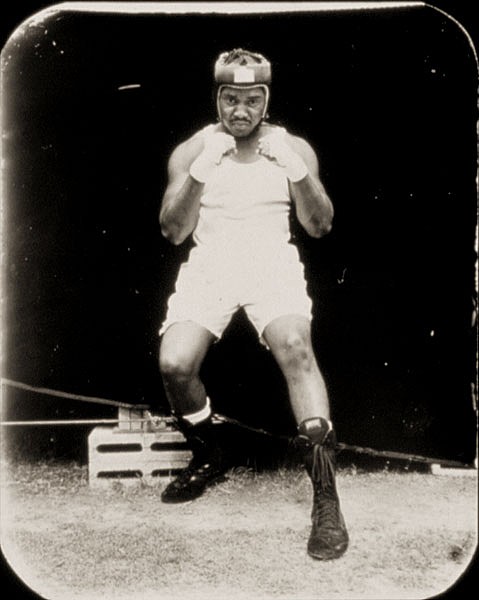

All these images are from HIDDEN FROM HISTORY. UNKNOWN NEW ORLEANIANS:

“The people grouped here may have had nothing in common except that their lives intersected with the municipality at least once. This exhibit brings them together in part to show how the city classified them. The documents and photographs here are therefore not representative of those New Orleanians who lived their lives quietly and within the law; they are necessarily skewed toward those who erred or strayed, who got caught or got in trouble, or, conversely, those who actively sought assistance from the city.”

The images were selected from the Louisiana Division/City Archives. My favourites here are those photographs in which intriguing, strong(?) communication persists.

– – –

The exhibit was curated by Emily Epstein Landau and funded in part by the Sexuality Research Fellowship Program (1999), a program of the Social Science Research Council, with funding from the Ford Foundation. Dr. Landau received her doctorate from Yale University in 2005. Her dissertation, “Spectacular Wickedness”: New Orleans, Prostitution, and the Politics of Sex, 1897-1917, is a history of Storyville, the famous red-light district. She will be teaching New Orleans history this Spring, as a visiting lecturer at the University of Maryland, College Park. She lives in Washington, DC.

There is a place in the US where two men have been held in solitary confinement for 37 years. It is Angola Prison, Louisiana.

Robert H. King, one of the Angola 3 was released when his wrongful conviction was overturned in 2001. Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox remain.

The length of their stays in solitary are due to the seriousness of the crime for which they were charged – the murder of a prison guard. They have always maintained they were framed for the jailhouse murder. Interestingly, in the In The Land Of The Free trailer the correctional officer’s widow doesn’t believe Wallace or Woodfox were the killers.

MENTAL HEALTH IN SOLITARY

For the most visceral and psychological description of solitary confinement upon the mental and physical health of a human read Atul Gawande‘s vital New Yorker article HELLHOLE (March 2009).

Every wondered what effect isolation has on the human psyche?

What a crazy world with inexplicable institutions.

‘IN THE LAND OF THE FREE’ STILLS

Solitary cell

Herman Wallace (left) and Albert Woodfox (right) with Angola prison in the 1970s (background)

Photos from the In The Land Of The Free facebook page.

Louisiana has the highest rates of incarceration of minors of any state in the country. Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate per capita of any state in the country.

It has now become the first state to sue its own death row inmates:

via Solitary Watch.

The absurdity of this gesture is fitting for a policy that only ensures time and resources are wasted on arguing the merits for and against killing people for symbolic purposes.

Get beyond the obvious – that is that the state shouldn’t be involved in de-existing people – it seems the main conclusion to be drawn is that hundreds if not thousands of jobs rely on the self-indulged death-industry toying with the fate of death-rowers for decades.

It seems to me that victims, victims’ families and those sentenced become a secondary concern; an infrastructure of legal jousting imposes itself, acquires its own logic and fights it out because that what the cogs demand. The results are laughably tragic deadlocks and bizarre gestures such as that of suing convicted individuals who are virtually powerless anyway.

My solution would not be to limit the legal avenues of appeal following conviction, it would be to abolish the death penalty as a sentencing option.

Just as the state should not be involved in killing people, it should not be involved in the retaliatory-posturing concerning the killing of people.

_________________________________________________

Previously on Prison Photography: There is a lot of inequalities within Louisiana’s criminal [in]justice system, that I have touched upon here, here and here. There’s also chinks of light in an unforgiving system such as radio and football programs at Angola.