You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Photography’ tag.

© 2009 Ged Murray

To append my last post about iconic photographs of rooftop inmates during the Strangeways riot of 1990 is a nod to the work of Ged Murray. Previous lamentations at the lack of Strangeways photography were premature on my part … I just had to keep digging.

© 2009 Ged Murray

These are my choice shots from a series of 20 Strangeways images on Ged Murray’s website. The image below of the two inmates in discussion is iconic (according to my brother). The silhouetted tower is instantly recognisable.

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

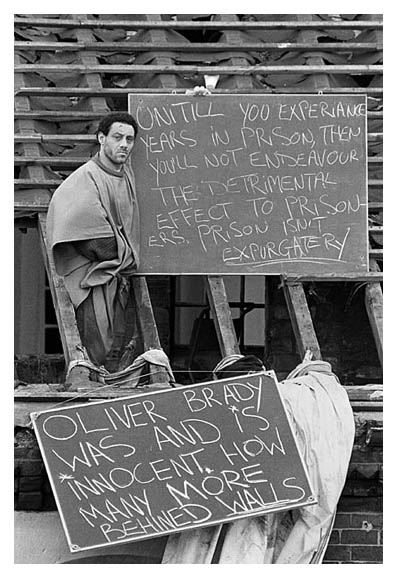

This last image of an inmate with signs took a large portion of my time. I am still thinking it over. Unerringly, I like the image. The shot bypasses the potency of icon and dilutes our consumption of events; returning our appreciation to more modest levels, focusing on the individual lives involved during a brief but pivotal moment in the history of British governmental prison policy.

© 2009 Ged Murray

__________________________________

Thanks to Ged Murray for his permission to publish the images.

The Strangeways riots in 1990 led to breakthroughs in the prison system. Photograph: Don McPhee for the Guardian

On April 1st 1990, began Britain’s largest prison riot in history. Strangeways may not mean a lot outside of the UK, but within, Strangeways, Manchester is synonymous with the romanticised image of the Northern criminal. The photographs of prisoners on the roof are iconic. Britons watched with shock.

Photo: Ged Murray for the Observer

Prison conditions had rarely been in public debate. Our level of shock was only equivalent to our level of apathy, prior. The general public were in awe of the unprecedented institutional collapse.

Prisoners occupied the roof for 25 days in front of round-the-clock media coverage. The protest ended when the final five prisoners surrendered themselves peacefully on 25th April.

The estimated damage was pegged between £50 and 100 million. The true cost for the HM Prison Service was lord chief justice, Lord Woolf’s subsequent damning report, which cited inmate frustration and poor prison conditions as a main reasons for the riot.

Photo: Ged Murray for the Observer

According to the Guardian – which includes a transcript of the prevailing exchange between proctor and prisoners – the stirrings of unrest began in the chapel following the 10am service. Prison officers evacuated the chapel and then (arguably) too hastily other areas of the prison. Inmates using keys taken from chapel guards released other inmates. Soon the overcrowded and understaffed facility was no longer in the control of government authority.

Strangeways roof protest photographs are iconic because their subject was so unexpected. Britain had harboured class and political confrontation much in the past. But in the miners strikes and clashes with police, football hooliganism, the general strike violence could be in some way predicted. The circumstances for those prior tensions had been played out through media narrative. UK Prisons were neglected; they were in desperate conditions and we – the public – were oblivious.

Don McPhee

Photographs of the Strangeways riot are hard to come by but I have gleaned a few from the web. In doing so I came across the work of the late Don McPhee.

I strongly urge you to watch this slideshow of his work.

McPhee had a 2005 exhibition at the Manchester Art Gallery and is a fondly remembered northern talent. He was a crucial part of the alternative editorial voice of the Guardian at that time. That distinctly Northern paper is now internationally distributed & respected.

Miners sunbathing at Orgreave coking plant. Photograph: Don McPhee

_______________________________________________________

Here is the inevitable percolating legacy of Strangeways in public dialogue.

Here, Eric Allison makes a succinct argument for British prison reform.

And here is the UK Parliament debate in 2001, ten years after the January, 1991 publication of Woolf’s report reviewing the response to the report recommendations.

In Germany, as in most European nations, prisons often lie within towns and cities; European prisons & jails are older than the housing estates and urban developments that, ultimately, came to surround them.

In Britain, castle-like Victorian-era prisons were the dominant type until the seventies when they were replaced by draft-proof, medium-sized institutions in rural locations. Bricks and mortar made way for concrete & razor wire. That said, a few town-centre “citadels” such as Preston Prison and Lancaster Castle still operate within Her Majesty’s Prison Service, the latter dating back to the 14th century!

In the American penal landscape, a high proportion of prisons (and all new builds) are outside of conurbations – sometimes isolated in the mountains or desert, sometimes just within grasp of a rural town to prop or establish a local economy.

Christiane Feser‘s photographs could not be mistaken as American, just as the New Topographics couldn’t be mistaken for anything but American. I don’t want to say Feser’s series Prisons is typically German, because I don’t know what that means. Instead, I will say it is typically Northern European. Feser’s photographs embody the spirit of pedantic spatial ordering which I have observed not only in Britain and Germany, but also Austria and the Netherlands.

We don’t know the specific locations of these prisons so we can not know the construction dates. Given the carceral/residential interplay we can say that if Feser’s images aren’t about the zoning of space, they are about a time before zoning dominated civic-planning.

“When I photographed the prisons I was interested in how these prison walls are embedded in the neighbourhoods,” said Ms. Feser via email. “How the neighbours live with the walls. There are different strategies. Its a little bit complicated for me to write about it in English …” Feser’s images do the talking.

Feser’s world is one of silence, order and manicured nature. Her images evince a harmony between the prison, its neighbours and vice-versa. We witness no trauma here.

Feser has obviously decided to omit humans from her compositions. The neighbourhoods are well tended and so presumably inhabited. One presumes the neighbourhoods are occupied daily, and yet we see no cars in driveways nor bikes on the street. Feser almost suspends belief. Are these actual places? Is this a toy-town?

Why does Feser rely on manicured topiary and brick pointing of the absent inhabitants to illustrate the “different strategies”? Is Feser suggesting a common psychology between prisoners and residents?

Have the neighbours adopted psychologies of seclusion and discipline as exist in the prison next door? Can penal strategies of control transfer by osmosis through prison walls and throughout a community? Or are certain personalities attracted to these new build estates? Are a portion of these homes reserved for prison staff? Or has Feser’s clever framing and omissions just led the viewer along these lines of inquiry?

Many would think in this peculiar carceral/residential inter-relationship the prison dominates, overbears. I doubt it. I contend those who live in such locales influence the institution also. The two agents in this relationship aren’t separate; they are drawn to one another and they overlap.

Feser uses visual devices to point toward this overlap. Angles of the oblique walls, dead ends, tended verges and brown-toned brickwork repeat through the series; sometimes these elements are part of prison fabric, sometimes part of a house.

There exists no hierarchical coda in Feser’s images as all the surfaces are equal. One has to pay attention to figure out which architecture is carceral, and which is not. Even the barbed wire doesn’t confirm it totally as (in England at least) one commonly sees barbed wire and glass shards lining the walls of merchant-yards and back alleys.

Feser’s photographs cradle a palette of grey concrete & skies; dense greens and the browns of brick & mortar. This is Germany, but it could as easily be Lancashire housing estates, Merseyside new towns or the reclaimed industrial sites of Scottish cities.

So how about it America? You are the land of the suburb and subdivision. You may not be familiar with a socio-spatial history that favours the awkward in-fill of urban and semi-urban space over the encroachment on to undeveloped land. It’s alright. Prisons needn’t be invisible and we needn’t be afraid. Locks and keys work as well on your street as they do in up-state, high-pain, back-water seclusion!

The location of prisons matters because when prisoners are sent to facilities on the other side of the state, families are likely to visit less. The commitment of time and money required to make such a lengthy trip usually precludes the poorest families from the essential and simple act of visiting a loved one. Research has shown the largest single factor in a prisoner successfully reentering society and not re-offending is the maintenance of family ties and the continued support it provides.

All images © Christiane Feser. Used with permission.

Capt. H.D. Smith of SUCCESS, Date Unknown. Glass negative. George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress). Call Number: LC-B2- 2611-3

A couple of weeks ago I gave a nod to subtopia’s article on Floating Prisons. This is a topic that gets more meaty the more contemporary the examples become. The intrigue levels reach new heights when the 21st century, nautico-military gun-vessels are spear shaped, warp radar detection and travel quicker than your average barracuda. Concomitantly, the further back one ventures, prison ships are mired in the shameful times of slavery and the dirty deeds of colonial conquest.

There is a period between these two paradigms, when American authority locked up American pioneers on prison hulks. When the western expansion became western settlement, predominantly centered about San Francisco, the authority of the time needed a “bulk” solution to the settling and incorrigible population. The quickest solution to the quickest lawlessness on the continent was the prison ship.

San Quentin Prison. Image: Telstar Logistics (Source)

In 1851, the first prison on the west coast of America was established at Point San Quentin, but when it was established it was not bricks and mortar but beams and gulleys. The Waban, a 268-ton wooden ship, anchored in San Francisco Bay, was outfitted to hold 30 inmates. Subsequently, inmates who were housed on The Waban constructed San Quentin which opened in 1852 with 68 inmates. Unfortunately, I could find no images of The Waban.

I think it is interesting that a “prison-as-terminal” was immediately necessary when humans reached the edge of a continent. San Quentin prison replaced the archipelago of local jails across America as a permanent and expanding facility – the final stopping point for California’s early lawless contingent.

It is poetic that the first penological-structure chosen (based on practical needs) was one that straddled land and water; permanently moored, but temporary in its utility. Carceral use demotes the ship to ‘container’ and The Waban, like its inhabitants, entered its demise.

Success convict ship, no date recorded. Image: Library of Congress

Anyway, just to prove its not all bad news for prison ships, above is one of the most famous. Success was reincarnated as a global museum traveling the world purportedly as a museum demonstrating the transportation horrors of the British Empire.

Here’s the skinny, “Constructed in built in Natmoo, Tenasserim, Burma in 1840. sold to London owners and made three voyages with emigrants to Australia during the 1840s. On 31 May 1852 the Success arrived at Melbourne with emigrants, and the crew deserted to the gold-fields, this being the height of the Victorian gold rush. Due to an increase in crime, prisons were overflowing and the Government of Victoria purchased large sailing ships to be employed as prison hulks. These included the Success, Deborah, Sacramento and President.

“When no longer needed as a prison ship as such, the Success was used as a detention vessel for runaway seamen and later as an explosives hulk.

“When the Victorian Government decided to sell the last of its redundant hulks, Success was purchased by a group of entrepreneurs to be refitted as a museum ship to travel the world advertising the perceived horrors of the convict era. Although never a convict ship, the Success was billed as one, her earlier history being amalgamated with those other ships of the same name including HMS Success that had been used in the original European settlement of Western Australia.

“A former prisoner, bushranger Harry Power, was employed as a guide. The initial display in Sydney was not a commercial success, and the vessel was laid up and sank at her moorings in 1892. She was then sold to a second group with more ambitious plans.

“After a thorough refit the Success toured Australian ports and then headed for England, arriving at Dungeness on 12 September 1895 and was exhibited in many ports over several years. In 1912 she crossed the Atlantic and spent more than two decades doing the same thing around the eastern seaboard of the United States of America and later in ports on the Great Lakes.

“The Success fell into disrepair during the late 1930s and was destroyed by fire at Lake Erie Cove, Cleveland, Ohio, while being dismantled for her teak on 4 July 1946. (Source)

Prison ship SUCCESS, Seattle, 1915. Photographer Unknown. Image: University of Washington Digital Archives

The Success passed through the Panama Canal and spent 1915/1916 on the Pacific Coast. She drew huge crowds in Seattle. I found the image above at the University of Washington Archives, which was my main reason for constructing this post. Success also docked in Tacoma in 1916.

Around 1916, the exhibition prison ship "Success," from Melbourne Australia, was docked at the Tacoma Municipal Dock Landing and open for tours. Marvin D. Boland Collection, Tacoma Public Library. Series: G50.1-103 (Unique: 31555) (Source)

I guess I just like the fact the Success was repurposed so many times and for a long period of time was a museum to the macabre. Some commentators were bothered by Roger Cremers recent World Press Photo win in the “Arts & Entertainment” category for his photographs of Auschwitz tourists. I guess ‘Dark Tourism’, or Thanatourism, has always existed. 21st century generations may not be as perverse as we perceive.

__________________________________________

Ettore Scalambra © 2009 Luca Ferrari

Luca Ferrari is a young documentary photographer who graduated recently from The University of Wales, Newport. In 2001, he gained a scholarship in Rome and chose to document the lives of inmates in his native Italy at Rebibbia Prison.

© 2009 Luca Ferrari

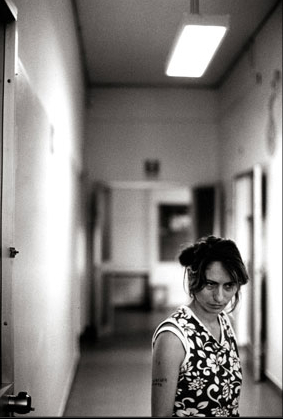

I have chosen seven of his most striking works. Ferrari’s portraits are accompanied by words spoken by the prisoners. I have only included a single testimony here and I encourage you all to take the time to visit his site to understand the subjects more. Ferrari offers the caveat, “I apologise if some of the text is long for internet reading, but they are an essential part of my work.” No apology needed. The necessity for the text is obvious; I would argue crucial.

I have included the words of one inmate discussing the experience of another at the end of this post. The words are hard to read. I jostled with the decision to include them or not. In the end, I decided if anything should come from an analysis of Ferrari’s work it should be to convey the real gravity of his subjects’ lives.

I also firmly believe that in the work of any documentary photographer, if the sitters and subjects stories stay in the audience’s mind longer than the photographer’s name then the photographer has succeeded.

Pierluigi Concutelli © 2009 Luca Ferrari

The Mass © 2009 Luca Ferrari

Giovanni Iacone © 2009 Luca Ferrari

______________________________________________

Alessia and Lucia

Ferrari interviewed inmate Alessia on September 10th 2003. She spoke of Lucia’s traumatic experiences and suffered injustice.

Alessia © 2009 Luca Ferrari

She is 42 years old. She comes from Ethiopia. She lives on the street – in the park at Piazza Indipendenza. She says she will go [be released] on the 22nd. She has a father and mother. They live her in Rome. Her parents have tried to help her but she cannot see a male person because five Italian guys have raped her. She was in the boarding school of Villa Pamphili and during the weekend she would go home. While she was at the bus stop waiting for the bus to go home, a car arrived and kidnapped her. They probably took her to a secluded place. It happened in the cell as well.

In fact, when they lock us up, she opens the water tap and fill sup the buckets, then she empties them on the floor. She then takes the toilet paper and puts it on the television screen. She does this to have the cell unlocked.

She has not been sane since she was raped. They did not only rape her they gave her a good thrashing. One of the guys made her pregnant and nobody knows the whereabouts of the kid. The social services gave him to another family.

Her parents took her to the hospital. She escaped and has never gone back. They attempted many times to help her, but nothing. She has been in a psychiatric hospital, where they bombarded her with electroshock. After this she was worse.

Lucia © 2009 Luca Ferrari

______________________________________________

Brief Q & A

When did you photograph the Rebibbia series and how many times did you visit?

I did the series during August 2001 and the summer of 2003. I can’t count the times, but almost every day for a month in 2001 and daily for one month in 2003.

Describe Rebibbia prison.

Rebibbia is a prison in Rome which holds 352 women and 1927 men. Within the womens’ ward there is also a special section for mothers with children under 5 years old.

What first got you interested in the subject of prisons?

I won a scholarship in Rome in 2001 to produce a exhibition on the theme of “Memory”. From that I showed my pictures to a publisher who was interested in making a book on Rebibbia. In 2003 I continued the work.

Why Rebibbia prison?

At that time I was living in Rome. Moreover, Rebibbia is one of the biggest and most important prisons in Italy.

What arrangements did you need to make to gain access to the prison (phone calls, letters, recommendations)?

I needed a letter of commission from the scholarship/publisher and also the permission of the prison authority.

Describe your interactions with the prison inmates/subjects and also the prison staff.

The permission I had was very restricted. I could not going everywhere, so I decided to add text to my pictures. The texts are not official interviews but chats I recorded in my notebooks. Sometimes the inmates gave me letters from their relatives or text written by themselves.

I tried to be as informal as possible with the texts. The prison institution is already very formal; As Erving Goffman described in Asylums it is a total institution. The status of a prisoner “is backed by the solid buildings of the world, while our sense of personal identity often resides in the cracks.”

I just tried to be a crack.

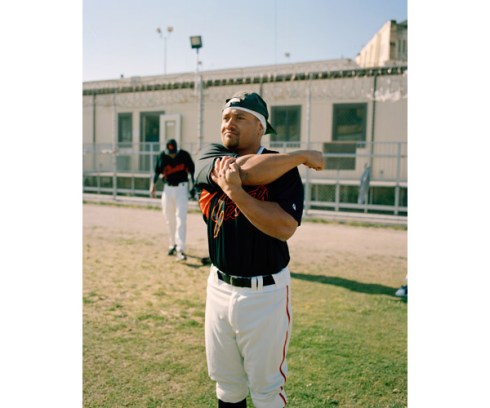

With Emiliano‘s permission I have lifted these images straight from his website. We are working together on an interview for a second post on his work (scheduled for next week). It will include previously unpublished and untouched images from his contact sheets. Please stay tuned for that. Meanwhile enjoy my personal selection of six preferred prints.

ALL IMAGES © 2009 EMILIANO GRANADO

_____________________________________________

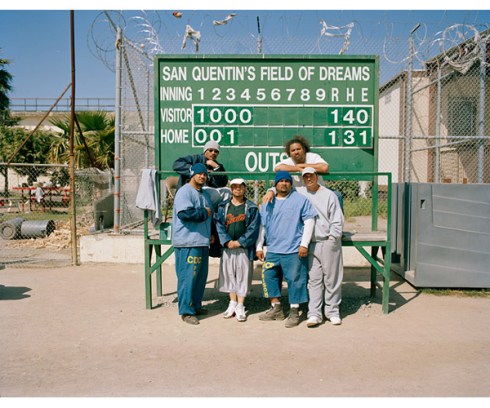

The San Quentin Giants are well known in the San Francisco Bay Area. I have met a couple of guys in the past who’ve played inside the walls during regular season – it is not unusual.

In an ideal world, the to and fro of public in and out of prison would be without restriction, threat or security protocol. This way, society could fear inmates less and inmates would not be institutionalised to the extent they are today.

I realise this is pie-in-the-sky thinking as the minority of seriously dangerous prisoners necessarily dictate the need for stringent controls. Still it doesn’t mean that increasingly trusted and regular contact between inmate and no-inmate populations cannot be our ideal to shoot for. Smaller and purposefully designed institutions would certainly be the first step in this sea change.

The scheduled games for the San Quentin Giants baseball team are the closest approximation to genuine & normalised interaction between inmate and non-inmate populations. When will San Quentin get a basketball team? Or any other teams for that matter?

____________________________________________

Check out these sources for further information on the San Quentin Giants. Press Enterprise – Long Article and Audio, Mother Jones article – Featuring Granado’s photography, California Connected – Video, Christian Science Monitor – Long article and video, NPR Feature – Audio.

And, if you are really engrossed you can always purchase Bad Boys of Summer, a recent documentary from Loren Mendell and Tiller Russell.

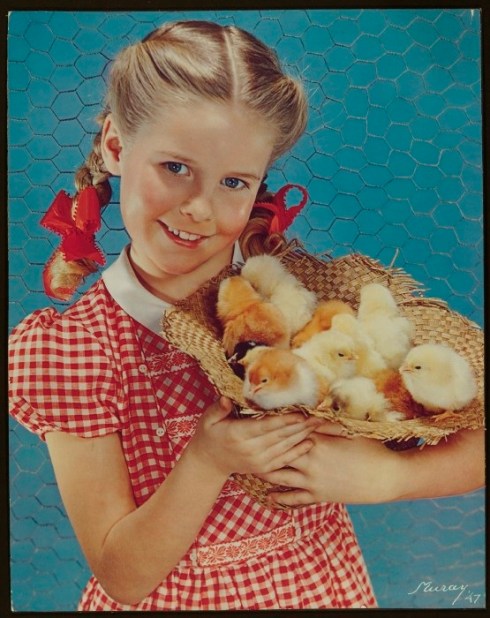

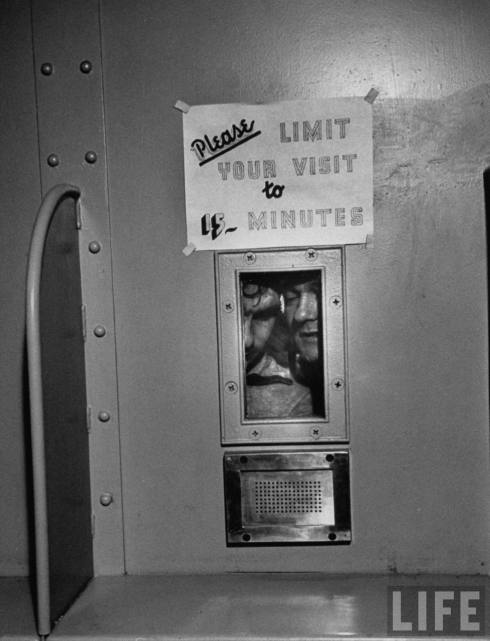

Woman in cell, playing solitaire. ca. 1950. Nickolas Muray. Transparency, chromogenic development (Kodachrome) process. George Eastman House Collection - Accession # 1983:0567:0151

I was blown away last month when the indicommons feed landed Nickolas Muray’s colour commercial photography on my desktop. Muray’s commercial work is fresh, witty, a sock in the eye and an all round feast of fun. The fact I haven’t any knowledge ofi the advertised products makes my enjoyment all the more visuocentric and naive. And that’s okay … every so often.

Pop music sprouted in the fifties, right about when this image was taken. I have Alma Cogan playing in my mind as I browse Muray’s commercial kodachrome prints. Visually, Woman in Cell, Playing Solitaire is an alterworld mash-up of Jehad Nga and Edward Hopper. Don’t you just dig those colours? None of the psychological edge though; the lady, despite being locked up, hardly looks harassed or without hope. Rather, she looks bored.

To continue the fest of technicolour, let me include the image below. Admittedly, it stretches the theoretical parameters of this blog but I would argue the subject is relevant. Depicted is the harsh subjugation of fowl to sites of incarceration – evidenced by the chicken wire and possibly even the girl’s well-disguised, maniacal grasp of the hat!

American Cyanamid Girl with Straw Hat Full of Chicks, 1947. Nickolas Muray. Color print, Assembly (Carbro) Process. George Eastman House. Accession # 1971:0048:0017.

To end on a serious note, I knew of the exceptional George Eastman House collection, but was frequently frustrated by the archaic platform of its website. Browsing was not fun. To GEH’s credit they recognised this enfeeblement and avidly committed important works to the Flickr Commons project. Kudos to them. We are all the better for it! I am just happy an image came along with vaguely carceral imagery, providing me an excuse to share.

_________________________________________

Nickolas Muray (American, b. Hungary, 1892-1965) immigrated to the United States in 1913, working first as a printer and then opening a photographic portrait studio in Greenwich Village in 1920. He became well known for his celebrity portraits, publishing them regularly in Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fair, Vogue, Ladies’ Home Journal, and The New York Times. After 1930, Muray turned away from celebrity and theatrical portraiture, and became a pioneering commercial photographer, famous for establishing many of the conventions of color advertising. He is considered the master of the three-color carbro process. Muray’s portraits of Frida Kahlo are well known and well-loved.

Kevin Van Aelst for The New York Times

I posted about Google’s collaboration with LIFE Magazine a few months ago. I – like many folk – were excited to dig in, ferret about and generally enjoy the visual culture of decades past. It seems the novelty has worn off for some. An excellent diatribe, Photo Negative, in the New York Times last week made the point succinctly.

“When Google first announced on its blog that the Life archive was up, it seemed like another Google good deed: rescuing the name of Life magazine and the glorious 20th-century tradition of still photojournalism. But Google has failed to recognize that it can’t publish content under its imprint without also creating content of some kind: smart, reported captions; new and good-looking slide-show software; interstitial material that connects disparate photos; robust thematic and topical organization. All this stuff is content, and it requires writers, reporters, designers and curators. Instead, the company’s curatorial imperative, as usual, is merely ‘make it available’.”

Prisoners watching baptism of repentant killer, in Harris County jail, TX, US. March 1954. Credit: John Dominis. ©2008 Google

With little in the platform or functionality to inspire users, Google could find visitors’ perusal time shrinking. Users might face unavoidable limits to their search time and patience. 15 minutes?