You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison’ tag.

Recruit Gill and other recruits shout as they count down from 10 after being ordered to "clear the head", which means to exit the lavatory area. When the count reaches zero, everyone is expected to have put away their toiletries and be standing in line.

A couple of weeks ago, before Theo Stroomer headed off to Bolivia, we sat down for a beer.

After studying photojournalism at the University of Colorado, Stroomer went to work as a photographer for a newspaper in Vail, Colorado. He documented the Colorado Correctional Alternative Program (CCAP) in Summer 2008 as a personal project.

The CCAP, a boot camp style program, was the only program of its kind in Colorado and one of very few across the States. The three-month camp, which opened in 1991, offered physical & mental challenges, a GED program and substance-abuse treatment. About 90% of the offenders had drug or alcohol abuse problems

In March 2010, as part of Colorado State budget cuts, the boot camp was closed down. “There’s no political consequence in making a decision like that,” says Stroomer. The photographer observed change and believed it was a worthy program. Upon hearing news of the closure, Stroomer wrote, “I held a high opinion of the program, its staff, and its role in the lives of inmate participants after observing it over a three-month period in 2008. I am sorry to see it go.”

Staff use a technique called "corralling" to discipline Recruit Cardenas on Zero Day, the first day of the three-month program. Zero Day is the most intense day for new recruits. They are subjected to extreme physical and emotional stress, including supervised physical contact from staff members.

Recruits are rushed off the bus on Zero Day. To break new recruits mentally and physically, staff bark orders constantly, move them on and off the bus repeatedly, and batter them with physical exercises.

Admittedly, the boot camp program was more costly than simply warehousing prisoners. And costs were rising; from $78/day to $109/day per inmate in 2009 alone. Also unhelpful were the gradually increasing year-on-year recidivism rates among CCAP graduates. The Denver Post, in a rather damning summary, reports:

51% of the 155 inmates released from prison through boot camp in fiscal year 2007 have already returned to prison. The 51% recidivism rate of these nonviolent offenders was only 2% points better than the record of inmates convicted of crimes such as robbery and murder.

Another huge problem for CCAP – which only took non-violent first-time offenders – was the statewide rising proportion of inmates classified as “high security” compared to when CCAP opened in the early nineties. Indeed, it is telling that as the CCAP boot camp was being shuttered as another new maximum security prison was under construction in Canon City.

It should always be noted that the most inventive and progressive programs are more expensive than those which simply lock people up without rehabilitation efforts.

Ari Zavaras, Colorado Department of Corrections executive director, rolled out the stats to support the decision. I suspect negatively-spun statistics surface about any particular service whenever a state department is about to bin it. The closure of CCAP boot camp is forecast to save $1million in operating costs per year and relocate 33 full-time staff.

Recruit Greene log-rolls in "the pit", a gravel area that is used for group discipline and physical trials that are rites of passage in the program.

Recruits Shock, center, Davis-Gonzales, left, and Gill, right, smile during Prison Fellowship, a nationwide Christian prison ministry program that meets once a week during CCAP.

The squad bay, where recruits keep their toiletries and clothing in addition to sleeping at night. With good behavior from the entire platoon, recruits can earn amenities such as pillows.

BOOK

The Pain the Pride (Waterside Press, 2000) by Brian P. Block is an exclusive fly-on-the wall account of life inside the Colorado Correctional Alternative Program. It is available on Google Books.

STATS

The Denver Post reports on the unexpected, welcome and only half-explained trend of decreasing prison populations in Colorado (2009: 23,186 – 2010: 22,127).

Why the surprise? Shouldn’t one expect a drop in prison population if the state ceases to pursue (due to budgetary constraint) harsh, punitive legislation of boom years? After the postponement of insane policy, we should be looking how to reverse the damage and plummet the figures further. In 1981, Colorado had fewer than 3,000 prisoners. That’s the baseline to focus on.

Graduate Davis-Gonzales hugs his girlfriend, Povi Chidester, during a graduation ceremony at the conclusion of the three-month program. Inmates who complete the program attend the ceremony and are allowed one hour with family and friends. Their sentences are then sent to a judge for reconsideration. "I came here from a huge house with a bunch of coke, a bunch of money, a bunch of guns ... and now I have none of that. And I feel like more of a person now than I did then," said Davis-Gonzales.

Golf Five Zero watchtower. Crossmaglen, South Armagh, Northern Ireland, UK. © Jonathan Olley.

Last month, I had a jolly nice chat with a jolly nice chap about what all this means at Prison Photography. Where’s this open journal taking me?

I said if I took this whole thing to the academy, it could be as simple as a historic survey: The Uses of Photography to Represent, Control and Surveil Prison, Prisoners and Publics in the United States (1945 – 2010).

I was encouraged to ditch the historical view and engage the modern. Ask myself, why should anyone care about prisons? Only a small minority care now and that status quo has remained for many reasons tied up in the antagonisms of capitalism. Would a historical survey change minds and attitudes or just lay out on paper the distinctions most people have already made between themselves and those in prison?

Perhaps people would care more if the abuse of human rights that exists within the criminal justice system of America were shown to impinge on everyone, not only on those caught in its cogs?*

What if we consider the methods and philosophies of management used by prisons and identify where they overlap with management of citizens in the “free” society. Think corporate parks, protest policing, anti-photography laws, stop and search, street surveillance, wire taps, CCTV.

My contention has always been that there was no moral division or severance of social contract over and through prison walls. For me it’s never been us & them; it is us & others among us put in a particular institution we call prison.

But, now I am seeing also, there is an ever decreasing division of tactics either side of prison walls. Strategies of management and technologies of discipline perfected in prisons have crept into daily routine.

What has this emphasis on containment and of monitoring – at the expense of education and social justice – done to our society and to our expectations of society?

SURVEILLANCE/CCTV IN PHOTOGRAPHY

And now for the tie in with photography…

Thinking about surveillance, obviously we have the big show at Tate from this Summer, Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance & the Camera with its devoted section to CCTV. (Jonathan Olley‘s work from Northern Ireland is the standout.)

But I always think back to Tom Wichelow‘s series Whitehawk CCTV (1999), possibly because he insists it is not a criticism of CCTV just a look at the politicisation of the human subject viewed through its lens.

Most remarkable in the series is the trio of images of the tragic site of a murder. They reveal to us that looking and bearing witness can be an act of respect as much as that of curiosity as much as an act of control. We are all compelled to look, but some observers are recording the feed and have a disciplinary apparatus to back it up.

Untitled (CCTV footage). Young family visits murder site. Brighton 1999. © Tom Wichelow

Untitled. Friends of murdered boy visit the site. Brighton 1999. © Tom Wichelow

Untitled. Resident reveals murder site outside her bungalow window. Brighton 1999. © Tom Wichelow

– – –

*There’s a simple argument that we all suffer because our tax dollars support a broken system that makes us no safer.

These pictures are presumably in Italy? Is this one prison or did you visit several?

This was seven different prisons in Sardinia and Sicily. Being from Sardinia it was a lot easier to get permission to photograph. I also knew someone in Sicily. But saying “easier” doesn’t mean it was easy. It took a year and a half to get my permission. Two of the seven prisons are juvenile facilities.

Why did you arrive at this subject?

Two things. Firstly, I was doing my BA in photography at the London College of Printing and I started photographing [London] prison walls in my second year. I have never done anything with those images; I never even scanned them. But they made me curious and for my final project I wanted to go inside. So, I sent letters to prisons here in London, but it was very hard to get permission. Being Italian, I resorted to try in Italy.

Secondly, the main thing that inspired me was Envoi a poem by Octavio Paz:

Imprisoned by four walls

(To the north, the crystal of non-knowledge

a landscape to be invented

to the south, reflective memory

to the east, the mirror

to the west, stone and the song of silence)

I wrote messages, but received no reply

It is absolutely beautiful, so simple.

What does Envoi translate as?

Envoi? It is a bit of a mystery. I was reading a book by Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, and on the very first page there is Paz’s poem. Now, Octavio Paz was Mexican, Henri Lefebvre is French, but I have never found this poem in Spanish of French. So, only the English version, yet the title is in French. Envoi means to “send out” and in French it is also used in a way that means not to just send out a letter, but to send out emotion … communicating emotion to other people.

This project was based around this poem. It is a poem that describes the four directions – north, south, east, west and these are the four walls. They describe the life of a prisoner.

But your photographs are of Sicilian and Sardinian prisons and yet your explanation seems to describe something more universal – something based in emotion, not in geography.

Precisely. I did not say where these prisons were on my website. It doesn’t matter where they are. It is about the idea of a reinvented life within four walls. Obviously, it doesn’t apply to every prisoner. If you only have a six-month sentence your cell is less important, but if you have a life sentence then I feel that experience is applicable to this poem.

Right, and within your images of cell interiors we can see details. Are you interested in individual objects? Do you want them to act as substitute for the inhabitant? For this is a common ploy – I am thinking of work by Jeff Barnett-Winsby and Jürgen Chill.

Yes and no. Let me jump to one of your other questions. You asked if it was my decision not to photograph inmates. Yes, it was deliberate, and beyond the fact it would be difficult to get permission. Again, based on this poem, I didn’t feel I needed to show these people.

I didn’t want to show a face. I thought it was enough to see their belongings and witness their presence that way.

What was the reaction of the inmates and staff at the prisons?

The staff didn’t understand why I wanted to photograph at the prison. They make jokes and suggest I should go to the beach to photograph, as it was “more beautiful down there.” That’s fine, they have a job and support their family and they’re happy that way.

The inmates were very enthusiastic. I mean, it’s a different day. A day different to all the other ones; to have a photographer come into your cell.

I was continually escorted except for at two open-prisons where I was free to go anywhere I wanted. Whenever I saw a cell I wanted to photograph, I had to ask permission from the inmate, not the guard. That made me understand that it was his house. I had to ask him, just as I’d ask you if I knocked on your door. Sometimes we’d have coffee. Some of the guys gave me recipes about how to make certain types of pastas. It was a very strong experience.

Do you know if any of the guys have seen your work – did you provide prints or may they have been released and looked it up online?

I grew up in an area of Cagliari that wasn’t the best so I knew some of the guys inside. Some of them were surprised to see me there; I was not so surprised to see them there.

As far as I know they are still in. There was another guy who was famous in the area for being involved in the mafia. He was on a life sentence. I expect not many have seen the work. Really though, I have no idea if they have looked at the pictures or not.

Is photography an adequate tool for communicating stories about prisons?

Yes it is, but you need to be very careful. You could make things a lot more dramatic. For example, I could have chosen a 24mm lens, got very close-up, shown rotten teeth of inmates … I could make it dramatic.

But, my position was a central position. Really, I know nothing [about prisons]. I didn’t, I can’t, stand on any side. I try to be neutral.

Tell me about your use of light.

I used long exposures. I wanted the light to flow from the windows. The light behaves as a one-way system; in the same way Octavio Paz’s poem spoke of writing messages but receiving no reply. In prison, communications are always interrupted; they become one-way communications.

At times “your” prisons seems quite spiritual? Was religion ever an undertone for your work? These could by cells that monks live in.

I’ve never thought of the spiritual aspect of the images. However in terms of environment, the ascetic life of a monk and the imprisonment of an inmate are not too different – only one is a choice, and the other not. Two of the prisons in Envoi used to be convents.

Pursuing that notion of religious visual cues – this isn’t a typical prison as we expect (in the US at least). Instead of barbed-wire, these prisons have rounded arches, some have vaulted ceilings. Some of the detail evokes ecclesiastical spaces.

The entrance with the rounded arch is the entrance to female section of the prison. This is in Sicily, which doesn’t have enough female prisoners to warrant a designated female facility. There were perhaps forty of fifty female inmates in this section.

I was actually quite intimidated by this gate – it was very heavy and very loud. It really gave the sense of being incarcerated.

How did you work while in a state of intimidation?

The first day I got in I took no photographs. I didn’t know where to start; immediately I felt like I’d got in too deep. Over time I got excited, I got focused. In Italy we have a saying that all things – good and bad – are felt in the stomach first. It’s the centre point of the body; everything important is felt there. I took these images after feeling emotion from the stomach.

How many times did you go to these prisons?

I went to Italy twice – both times for a month. I visited some prisons only once, others eight or ten times. I visited the prison in Cagliari, my hometown the most.

Did you do any research before the project? Did you look at other photography done in prisons?

Lucinda Devlin’s Omega Suites was a huge inspiration. Her work is beautiful.

Another project I like is Ghetto by Broomberg and Chanarin, although they completed it since Envoi (which was done in 2003). Broomberg and Chanarin photographed in South Africa and in Central and South America, not just in prisons but other institutions.

Yes, I have looked at their work before. My conclusion was that they now have the luxury of reputation, time and money to take a very slow approach to their photography. That is how I explain their remarkable results.

I think they deserve all the recognition they get. Their work is astounding. I was in a show last year, which also had their work. Their prints are amazing.

Tell us about your exhibition of Envoi?

It was a bit problematic. Firstly, I think they [The Ministry of Justice] gave me permission to photograph in order to get rid of me.

After the project, I wanted help to organise an exhibition. The exhibition I had in Sardinia was great but it was also a compromise.

The Ministry of Justice didn’t provide me money but they involved the town hall and private galleries and it became good publicity for them.

I used them and they used me for their own interests. They never understood my concept. They kept advertising the show as a one about Sardinian and Sicilian prisons and I kept telling them it was about a broader concept.

In the exhibition I used labels beneath the images to identify each prison.

[At the opening] I didn’t want to give a speech but they forced me. The Ministry of Justice didn’t really know what to say either but they had to say something; it is politics.

What are your politics on prisons now?

This was the first and only experience I have of prisons. I made my own personal interpretation of prison, but I don’t really know what happens inside. I want to take the position that this exists and is part of our society. Now in America, as you’ve said, there are the most prisons in the western world, and that is something relevant, but the way I looked at it from the start was that I was not going to make a judgement. I was curious about this place. It is a place we’d not want to experience but [about which] we’re all curious. My father was a cop and he worked in the anti-narcotics division for many years. He’d go to interview people inside jail. As a teenager, I always wanted to join him.

Do you aim to inspire curiosity?

The show was quite successful. Somehow people were reading what I was reading. I could see the majority of people reacting as I expected which doesn’t happen with my other projects! [Laughs] Generally, I was happy with the comments.

I did hear many people at the exhibition say, “It [prison] is not as bad as I expected.”

How did you respond to those readings? Did you challenge your audience?

No. I mean they didn’t see what I saw and they didn’t hear the doors slamming. Every step you take, there’d be another door closing at your back, one after another. It took a long time to get through the prisons.

Do you consider your images a literal description of the space. Is that enough?

No, no, certainly not and it is not enough. “This is the concept of prison and it is in these 20 pictures?” No, no, no, no. [laughs]. It is one piece of truth in an infinite world.

What are you working on now?

I am working on observations of tidal movements, the change in landscape. It is a study of seaside societies and the way they relate to coastline. I have visited Norfolk a lot – it’s amazing. In Italy you have the sea, the beach – it is always there, you don’t have these movements.

In Norfolk and other places, I take two pictures; one at low tide, then I wait six hours and take one at high tide.

Soon, I’ll be taking up a residency in Holland – the BADGAST residency – and I’ll look at Dutch sea society. Then, maybe Canada. Nova Scotia has the largest tidal movements in the world – as large as 52 feet!

Thank you Danilo.

Thanks Pete.

To see more of Envoi and Danilo’s other portfolios visit http://www.danilomurru.com/

ALL IMAGES © DANILO MURRU

How often when a teenager does something totally awesome does it get acknowledged? Not often enough?

This is awesome.

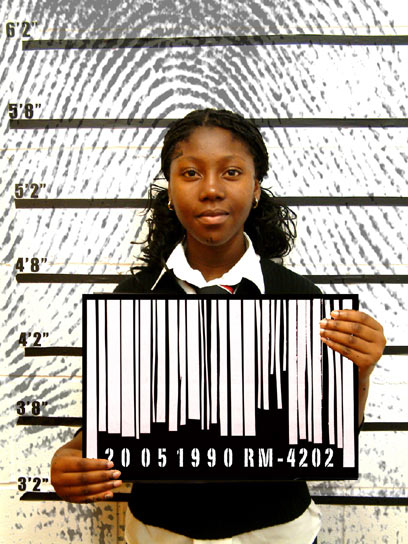

"Prison" by Siever Karim, 2005. As part of the Image & Identity Young People’s Conference at the V&A.

Siever’s Statement:

‘My ideas were based on conformity, and the suppression of cultures and personal individuality by being a number, wearing a uniform, being trapped in the cages of the social machine. I created my own police height chart and got my classmates to stand in front of it. I also made digital barcodes to symbolise the gathering of information which can be accessed so easily today.’

Image & Identity Artwork Project, Victoria & Albert Museum, 2006

WAR

In many ways I am surprised it has taken so long for a reel of film to make such an immediate impact on American audiences. The wikileaked military footage Collateral Murder shows us exactly what war is; war is the erasure of doubt, benefit of doubt in the face of procedure. The procedure of war is to kill.

Photographer Namir Noor-Eldeen runs for his life in the midst of a US 30mm machine-gun assault

Following the helicopter gunman’s requests to engage, the wait for the permission is one of the most haunting silences I’ve heard. And then, murder. Is it any wonder PTSD follows such carnage?

PRISONS

Ever since Change.org published With 140,000 Veterans in Prison, We Can Do Better last Veteran’s Day I have been aware of stories about the links between violence and suffering abroad with violence and suffering within US communities.

This week two stories surfaced – one from either side of the Atlantic – which illustrate two common scenarios for returning service men and women. The first is clinical depression in the from of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and the second is clinical depression in the form of addiction and aggressive behaviours.

At the Mid-Orange Correctional Facility in Warwick, N.Y., service dogs share a room with the prisoners who help train them. Photo: Stephen Crowley/The New York Times

PTSD

Stephen Crowley visited Mid-Orange Correctional Facility in Warwick, N.Y. to document the Puppies Behind Bars program. (I have mentioned this initiative before at a NY womens prison).

The program at Mid-Orange serves as rehabilitation in the form of responsibility, “softening up” and purpose in the direct service to outside communities. One of the growing communities to benefit from personally trained service dogs are America’s war veterans.

Staff Sgt. Aaron Ellis, suffering from PTSD had not been to the supermarket in three years until his prison-trained service dog gave him the confidence to step into the stimulating environment.

Watch the New York Times’ slideshow A Canine Treatment for PTSD.

CRIME

The Times Newspaper (UK) published From Hero to Zero reporting the fortunes of three ex-soldiers who’ve done time. Their addiction and aggression is often the result of either undiagnosed or untreated PTSD. The Times:

There is a widespread belief that post-traumatic stress disorder, occasioned by Britain’s engagement in two brutal wars, is behind the large numbers of veterans who offend. The truth is muddier. PTSD normally takes several years after the traumatic event to set in.

The Howard League for Penal Reform has launched an independent inquiry to bring this to public attention in the UK.

Former UK soldier, Michael Clohessy sleeps with a sword under his pillow. Photo TIMES Newspaper, UK

One of the biggest stumbling blocks for understanding and working to improve the prospects of the veteran/prisoner population is that the exact figures are not known and estimates vary wildly. The Times:

We send too many ex-servicemen to prison. How many, nobody is sure. A recent study by the National Association of Probation Officers (Napo) estimated that there may be as many as 8,500 ex-servicemen in prison out of a total prison population of 92,000. Harry Fletcher, assistant general secretary of the organisation, believes that around 8% of Britons in jail are from the forces. The vast majority of these offenders are from the army, and a large majority of the ex-army are from the infantry. But other groups have taken issue with Napo’s findings. The Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Defence conducted their own survey, which they published in January, concluding that only 3% of the prison population were former members of the military — around 2,500 veterans in total.

I think the title of the Times piece suggests it all – From Hero to Zero.We freely project the character of a man based upon our knowledge of his or her publicly performed actions. This is okay, but it mustn’t be only form part of our assessment. Heroes are never heroes, and zeroes are never zeroes; they are stereotypes. Stereotypes are often benign but sometimes damaging and paralysing to good judgement.

WHAT TO THINK?

Our prisons are filled with a wide variety of people with a wide variety of faults, competencies, potential and histories. For the most part, the authorities are aware of this, but I am not always convinced the public is.

Is it in our interest to think of these diverse populations in prison? Does this affect how we consider prisons and prison reform?

What do we need to see (photography?) – as well as read – to think of prisons in more reflexive ways?

Inmates in Discussion © 2009 Ged Murray

It might be that the anniversary of the most famous riot in the history of the British prison system will become an annual feature on Prison Photography?

Last year, I noted the 19th anniversary of the Strangeways Riot with looks at the work of Ged Murray and Don McPhee. This year for the big 20, I’ll point you in the direction of Ciara Leeming, fellow blogger, Northerner and Thatcher-basher. (Why is it that we children of the late seventies/early eighties can’t get out from under the iron lady’s shadow?)

Ciara:

Ciara’s just written a piece for Big Issue in the North, the UK’s magazine sold by homeless vendors in cities up and down the Isle. Download Ciara’s Big Issue feature here.

Constitution Hill is a former prison that used to hold political prisoners during apartheid, including both Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi.

Now the prison, a repurposed art space, faces a new controversy. Lulu Xingwana, a South African government minister, walked away from her official speaking engagement because she considered the images of lesbians immoral and “against nation-building”.

Zanele Muholi, an award-winning activist and artist has expressed her disappointment.

As the Guardian reports:

This is an understandable position.

The Guardina summarises:

It is within this context of ongoing violence toward women, that I think Muholi’s pitched her response to Xingwana perfectly,

“There is nothing pornographic. We live in a space where rape is a common thing, so there is nothing we can hide from our children. Those pictures are based on experience and issues. Where else can we express ourselves if not in our democratic country? Children need to know about these things. A lot of people have no understanding of sexual orientation, people are suffering in silence.”