You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Rencontres d’Arles’ tag.

At this years Les Rencontres d’Arles Photographie Festival the official photographs of the French prison inspectorate make up an exhibition entitled Behind the Walls of Cliche.

The independent French prison inspectorate (contrôleur général des lieux de privation de liberté) is nominated for six years and during that time he cannot receive any instruction from any authority; he can be neither removed nor renewed; and he cannot be prosecuted for his opinions he formulates or for the actions he carries out in his functions.

Currently, the director is Jean-Marie Delarue (here’s an interview with him about the state of French prisons).

Delarue’s team take photographs as documentation as they tour France’s prison system and it is these images that are currently on show at Rencontres d’Arles.

To my mind, this is a truly unique exhibit. I know not of any other arts festival that has put front-and-centre the administrative photography of a working independent or government agency overseeing prisons.

BLURB FROM LES RENCONTRES D’ARLES SITE

Sixty thousand detainees in French prisons: surely the problem can’t be all that hard to solve!

The Rencontres, in their own way, are part of the media, and this exhibition based on the report of France’s Inspector General of Prisons, Jean Marie Delarue, shows just how the world of French gaols, far from being an aid to social reintegration is, rather, an insult to the human condition. This is a call to look beyond the standard ideas about prison.

The exhibition also demonstrates the limitations of photography, which cannot convey the nuances of everyday unhappiness in prison. In a photo a TV set, a workshop and a library seem to offer possibilities which in fact are non-existent for most prisoners, and certainly not available on a regular basis. The rules of hygiene and safety are flouted every day, the psychological stresses are chronic, and the laws regarding the minimum wage and access are broken by the state itself. None of this is visible in a photo.

Pictures of a new prison seem to suggest a solution; but the image doesn’t tell you that new prisons have a higher suicide rate than old, dilapidated ones. Three people in a cell is something you can see; but what you don’t see is that one inmate standing means two lying down, because there’s nowhere to sit. And with prisoners spending 22–24 hours a day in their cells, it’s easy to imagine their physical and psychological state.

This is definitely not photojournalism, but rather an alarm signal regarding one of democracy’s least well known instruments.

François Hébel, exhibition curator

Excerpt from Law no. 2007-1545 of 30 October 2007:

’The Inspector General of Prisons is an independent authority whose duty it is, without prejudice to the prerogatives attributed by the law to the judiciary or jurisdictional authorities, to monitor the conditions of incarceration and transfer of persons legally deprived of their freedom, so as to ensure respect for their fundamental rights.

Within his field of responsibility, he takes no orders from any authority… He cannot be relieved of his duties before his term has expired… The authorities in charge of places of imprisonment cannot oppose a visit by the Inspector General except for grave, imperative reasons relating to national defence. The Inspector General may demand from those authorities all information and documentation required by the carrying-out of his mission. In the course of his visits he may speak, under circumstances guaranteeing the confidentiality of what is said, with any person whose participation he sees as necessary.

At the end of each visit the Inspector General makes known to the relevant ministers his observations regarding the state, organisation and functioning of the site visited, and the condition of those imprisoned there… Each year the Inspector General submits a report to the President of the Republic and to Parliament. This report is made public.’

The 2009 report is published by Dalloz.

PREVIOUSLY ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

I’ve noted French prison photography before. From Jean Gaumy, the first photojournalist in the French prison system to contemporary artist Mathieu Pernot; from the archives of Henri Manuel to portraitist Phillipe Bazin; and to the recent exhibition Impossible Photography – artistic survey of French prisons.

– – –

Of course, if you want to get really involved check out Melinda Hawtin’s French Prison Photography graduate work.

France even has its own National Museum of Prisons!

– – –

Thanks to Yann Thompson for the tip!

There’s been a few parallels drawn between cameras and guns recently.

Gizmodo reflected upon new laws that would suggest that to wield a camera is to act as a dissident and warrant attention from the police. Carlos Miller continues to collate “interactions” between photographers and law or security enforcement.

Fred Ritchin picked up on this drawing parallel between the Wikileaks video of the Iraq helicopter assault and the photographing of on duty police officers, “the former is certainly prohibited by law, and the latter is now also prohibited by law in some states. Both issues relate to the conduct of military/police forces and the inability of people to publish imagery that may point to excesses.”

Susan Sontag usually crops up when one discusses the violence of photography. Whether or not Sontag was the first to coin this notion I don’t know. I do know her writing about quite complex things can be beautiful, clear and accessible so perhaps she deserves recognition for simplifying and readying the idea that photography can be/is aggressive.

On the other hand, David Goldblatt – as Fred Ritchin argues – was a dispassionate practitioner who shied away from such comparisons.

Goldblatt, “I said that the camera was not a machine-gun and that photographers shouldn’t confuse their response to the politics of the country with their role as photographers.”

Goldblatt was not a dispassionate man, but a photographer who maintained a distance, developed his own language and avoided many of the frightful images that, for example, the Bang Bang Club produced for the world’s media.

Shoot! Rencontres d’Arles

In light of these recent commentaries, this exhibition review in The Guardian (originally in Le Monde) caught my attention:

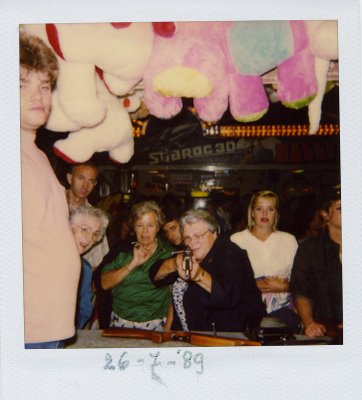

In Shoot! Clément Chéroux, a curator at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, returns to a once popular fairground attraction. When it first appeared in the 1920s, target-shooting enthusiasts could take home as a prize a photo of themselves in action. When the bullet hit the bull’s-eye, a portrait was taken automatically. By the 1970s the attraction had disappeared, but there is no nostalgia here. “I’m not paying tribute to a vanished process,” says Chéroux. “What interests me is its metaphorical side. […] Of the 60 or so exhibitions at this year’s Rencontres d’Arles the most successful and original is certainly the one on the photographic shooting gallery.“

With work from Patrick Zachmann, Christian Marclay, Martin Becka, Rudolf Steiner and Erik Kessels the exhibition is a varied interpretation of camera and gun, or in the majority of these cases, camera and rifle. Looks like a unique and winsome show. More here and here.