You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Steve Dickison’ tag.

Over two million individuals are behind bars in U.S. prisons, living in isolation from their families and their communities. Prison/Culture surveys the poetry, performance, painting, photography & installations that each investigate the culture of incarceration as an integral part of the American experience.

As eagerly as politicians and contractors have constructed prisons, so too activists and artists have built a resistance. Nowhere are these two forces pushing against one another as forcefully as in California. The book, Prison/Culture, compiles the documents of a two year collaboration between San Francisco State University, Intersection for the Arts (one of San Francisco’s oldest art non-profits) and prison artists & outside activists across the US.

Mark Dean Johnson’s essay summarises the visual/cultural history of incarceration; from Gericault’s institutionalized mentally ill subjects and his paintings of severed heads as protest against capital punishment, to Goya’s prison interiors of the inquisition; from Alexander Gardner’s portrait of Lincoln’s assassin Lewis Payne (1865), to Otto Hagel’s portrait of Tom Mooney (1936); and from Ben Shahn’s murals against indifference to the conditions of immigrant workers (1932) to the work of Andy Warhol and David Hammons in the modern era.

Johnson guides this lineage to the Bay Area, describing how Michel Foucault’s book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison became the conversation topic of Bay Area coffeehouses and classrooms (Foucault began lecturing at UC Berkeley in 1979). The swell of interest in Foucault’s structuralism coincided with a grassroots expansion of prison art in the early 1980s.

For text, the editors of Prison/Culture made two canny and provocative choices: Angela Y. Davis and Mike Davis (no relation).

THE TEXT

Firstly, in a 2005 interview, America’s most notorious prison abolitionist Angela Davis sets out – in her most accessible terms – how our prison industrial complex serves primarily as a tactical response to the inadequate or absent social programs following the end of slavery. Abolition was successful in that it redefined law, but it failed to truly develop alternative, democratic structures for racial equality. Powerful stuff, yet even newcomers to Davis’ argument won’t be as shocked as they may expect to be. She’s that good.

Next up, Mike Davis’ 1995 essay ‘Hell Factories in the Field’ is a bittersweet ‘I-told-you-so’-inclusion. Davis has made a specialty of dealing with – in stark academic prose – disaster scenarios, race-based antagonism and the environmental rape of recent Californian history. When Davis witnessed the mid-nineties expansion of the prison industrial complex (or as Ruth Gilmore Wilson terms it ‘The Golden Gulag’) he foresaw prisons’ economic band-aid utility for depressed towns; foresaw the mere displacement of violence; foresaw the assault on fragile family ties; foresaw the unconstitutional prison overcrowding and predicted the collective collapse of moral responsibility.

Davis’ article focused on the then new California State Prison, Calipatria – and not in a dry way. Paragraphs are devoted to recounting the installation of the world’s only birdproof, ecologically sensitive death fence following impromptu electrocutions of migrating wildfowl. The editors note, as of 2008, Calipatria’s facility design of 2,208 beds was 193% over-capacity with 4,272 inmates. Where birds saw an improvement in their lot, prisoners certainly did not, have not.

THE ART

Contributors include some well-known names – RIGO, (here on PP) Sandow Birk, Deborah Luster and Richard Kamler whose works address incarceration, criminal profiling, wrongful conviction, prison labor, and the death penalty. The book also includes poetry by Amiri Baraka, Ericka Huggins, Luis Rodriguez, Sesshu Foster and others but I shall not comment on these wordsmiths (their work is beyond my purview) other than to say they are talented and politically in the right place.

Special mention must go out for Deborah Luster’s One Big Self project (more here). In my personal opinion, it is the single most important photographic survey of any US prison. It is certainly the most longitudinal. Over a five year period, Luster visited the farm-fields, woodsheds, rodeos and national holiday & Halloween events throughout Louisiana’s prisons. She became a loved and recognized figure among the prison population; she estimates she gave away 25,000 portraits to inmates. Luster’s conclusion? Even mass photography struggles to communicate the vast numbers of men and women behind bars.

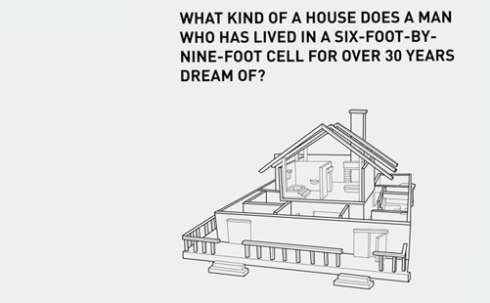

In 2003, artist Jackie Sumell collaborated with Herman Joshua Wallace (one of the Angola 3) on the design of his “Dream House”. The project The House That Herman Built is heartbreaking and bittersweet.

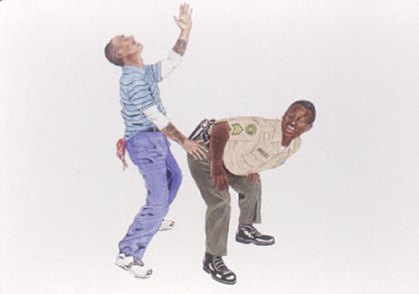

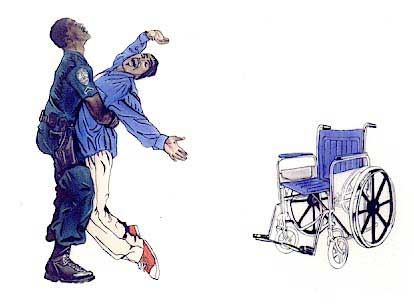

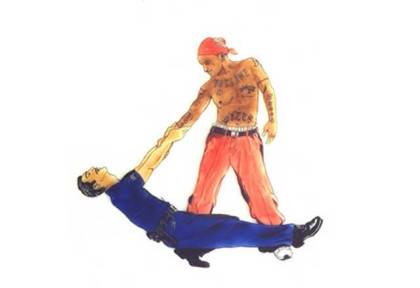

Alex Donis employs cunning and cutting humour for his series WAR. He sketches criminal “types” with figures of authority (policemen, prison guards) mid-dance, often bumping and grinding. He even conjures a kiss between Crips and Bloods gang members.

Also unexpected is the visual testimony of condemned mens’ last requested meals. For The Last Supper, Julie Green painstakingly painted porcelain plates with the last meals of nearly 400 executed men. Grayson Perry won the Turner Prize a few years ago, in large part due to his vases of abuse, bigotry and social ills. This clever use of regent materials has also been adopted by Penny Byrne for her Guantanamo Bay Souvenirs which sets up interesting parallels and a new turn for discourse between US homeland prisons and those used for the “Global War About Terror” (GWAT).

Relating to GWAT, Aaron Sandnes established a sound sculpture in which gallery visitors were subjected to the same pop songs used in Psych-ops by police and military interrogators.

Dread Scott‘s use of audio is intentionally to give silenced men a voice. (Scott has talked about the primacy of audio in his exhibition of prison portraits previously at Prison Photography).

Mabel Negrete collaborated with her brother incarcerated in Corcoran State Prison. She mapped out the floorplan of his cell as compared to her apartment bathroom. She then developed a dramatic dialogue in which she played both herself and her brother. (No images unfortunately.)

Traced – but essentially fictional – lines of structure are fitting for San Francisco, the city in which world-famous architect/installation artists Diller & Scofidio got their start with the architectural memories of the Capp Street Project. Negrete’s CV is extensive, she was instrumental in organising Wear Orange Day, a prisoner awareness action. Also check out her Sensible Housing Unit.

Cross-prison-wall collaborations are vital to the project as a whole; so much so, that without input from prisoners, the entire enterprise would fall short. Primarily, it is the men of the Arts in Corrections: San Quentin run by the William James Association who deliver acrylics and oils of optimistic colour and profound introspection. More here.

Collaboration as delivered in a multimedia and digital format comes by way of Sharon Daniel’s Public Secrets. Public Secrets “reconfigures the physical, psychological, and ideological spaces of the prison, allowing us to learn about life inside the prison along several thematic pathways and from multiple points of view.”

In closing, it is worth noting that San Quentin prison (only 12 miles north of San Francisco) has one of the few remaining prison arts programs in the state following 20 years of cut backs. The works in Prison/Culture challenge – as Deborah Cullinan & Kurt Daw, in their foreword, suggest – “traditional boundaries between inside and outside, between professional and amateur, between institutions and people” and, “by juxtaposing work by professional artists with artists who are working inside a prison, this book challenges us to rethink notions of community and culture.”

Prison/Culture is simultaneously a consolidation of achievement, a fortification of resources and celebration of resistance. This may be a book with a Californian focus, but it has national and international relevance. Succinct, well researched, egalitarian and lively. For me, Prison/Culture is the best collection of works by any US prison reform art community up until this point in history.

The resource list of over 80 organisations at the back of the book (page 92) is ESSENTIAL reference material for anyone looking to commit energies into prison art programs. All told, this book is a must read for those interested in the artistic landscape of our prison nation. It powerfully exposes the vast gulf between criminal justice and social justice in US society.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Prison/Culture is published by City Lights, edited by Sharon E. Bliss, Kevin B. Chen, Steve Dickison, Mark Dean Johnson and Rebeka Rodriguez.

Read a Daily Kos review here, and view images from a 2009 exhibition here.

City Lights Celebrates the Release of Prison/Culture

On Thursday, May 6 at 7:00 pm, join Steve Dickison, Jack Hirschman, Ericka Huggins, and Rigo 23 for a reading and book release celebration at City Lights Books. Tune in to KQED Forum at 9:00 am PDT the morning of the event for an interview with the book’s editors and contributor Angela Davis.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Images (from top): PRISON/CULTURE book front; Sandow Birk; Deborah Luster; Exhibition views of The House That Herman Built; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Julie Green; Julie Green; Ronnie Goodman, San Quentin inmate, displays his work; and ‘Public Secrets’ screenshot.