You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Washington’ tag.

These images are the result of a collaboration between photographer Steve Davis and the girls of Remann Hall Juvenile Detention Center, Tacoma, Washington State in the US.

Davis was forced to think of the camera as a tool for different ends, essentially rehabilitative ends. For legal reasons and the protection of minors, Davis and his female students were not allowed to photograph each others faces. It became an exercise in performance as much as photography.

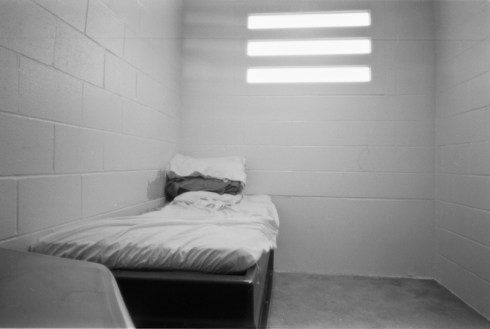

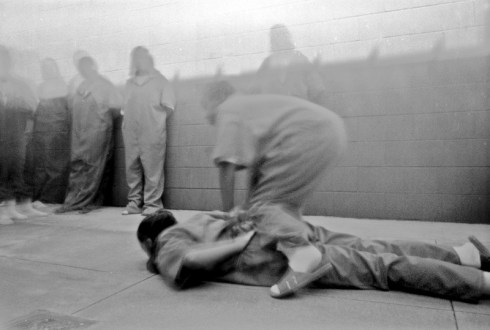

We see portraits of the girls with plaster masks, heads in their hands. The girls limbs outstretched made use of evasive gesture. The long exposures of pinhole photography resulted in conveniently blurred results.

PINHOLE PHOTOGRAPHY vs ROTE DOCUMENTARY MOTIFS

Photography in sites of incarceration often depicts amorphous, vanishing forms within stark cubes; it is usually black & white, and often from peep-hole or serving-hatch vantage points. When this vocabulary is used and repeated by photojournalists, visual fatigue follows fast.

Heterogeneous architecture doesn’t help the documentary photographer. Limited and repetitious visual cues make it tough to work in prisons. Images, shot through doors, by visitors only on cell-wings by special permission, are dislocating and sad indictments of systems that fail the majority of wards in their custody.

I celebrate all photography shining a light on the inequities of prison life. Having said that, very occasionally – only very occasionally, do I wish a “prison photographer” had expanded, waited or edited a prison photography project a little longer … but I do wish it.

Photojournalism & documentary photography have taken a battering from within and been asked some serious reflective questions. I don’t want to accuse photographers of complacency. To the contrary, my complaints are aimed at prison systems that so rarely allow the camera and photographer to engage with daily life of the institution.

Therefore, I stake two positions on the issue of motif/cliché. First, repeated clichés have developed in the practice of photography in prisons. Second, prison populations have had little or nothing to do with the creation, continuation or reading of these clichés.

As a general criticism, I would say photographers in prisons struggle to achieve original work. But, prisoner-photographers – whose experience differs vastly from pro-photographers, custodians and visitors – cannot be held to that same criticism.

WHEN THE PRISONER CONTROLS THE CAMERA

These images by the girls at Remann Hall are distinguished from the majority of prison documentary photography, because the inmate is holding the camera. When an inmate repeats a motif it is not a cliché.

These are images of all they’ve got; concrete floors, small recreation boxes, steel bars, plastic mattresses and chrome furniture … all the while lit brightly by fluorescent bulbs and slat windows. These aren’t images taken for art-careerism, journalism or state identification. These are documents of a rarefied moment when, for a while – in the lives of these girls – procedures of the County and State took back seat.

When a member from within a community represents the community, the representation is above certain criteria of criticism. A prison pinhole photography workshop has very different intentions than any media outlet. Cliche is not a problem here; it is a catalyst.

The simulation and reclamation of visual cliche (in this case the obfuscated hunched detainee) is doubly interesting. Why the frequent use of the foetal position? Why did the girls choose this vulnerable pose to represent themselves? Was it on advice? Was it mimicry? Was it part of a role they view for themselves? Why don’t they stand? Emotionally, what do they own?

As in evidence in some images, one hopes that some of these girls are friends. This selection of shots share a single predominant common denominator; the psychological brutality of cinder block spaces of confinement. Companionship seems like a small mercy in those types of space.

These photographs should knock you off your chair. I am in doleful astonishment. In the absence of faces, how powerful and essential are hands?

For now, consider how visual and institutional regimes square up.

Since the original publication of these images, they have been viewed tens of thousands of times. More than any other photographer – famous or not – these images by anonymous teenage girls have been by far the most popular ever featured on Prison Photography. That appetite shows that when prisons and struggle and creativity are presented in a meaningful way, images can be used as a segue into wider discussion of the underlying issues.

The Remann Hall project was done as a part of the education department program at the Museum of Glass in partnership with Pierce County Juvenile Court. This comment sums up the importance but also the fiscal fragility of these arts based initiatives:

“The Remann Hall project was an incredible project, which culminated in an outdoor installation at the museum and many of the participants coming to volunteer and participate in education programs at the museum after they were released. It was one of the many incredible programs I was lucky enough to be part of there. A book of poetry, artwork (and I think some of the photos in that link) was produced as well. The whole program was a great model for how arts organizations can do meaningful outreach in their communities. Unfortunately, the program was cut one year before the planned completion, due to budget concerns.”

[My bolding]

Inmate Jeff Curbow, 40, says he improved a watering system for the moss after others built a special hut for it at Cedar Creek Corrections Center in Littlerock, Thurston County. Credit: Ken Lambert / The Seattle Times.

Prison Photography always looks to visual sources that represent incarcerated peoples from a different perspective. Some of the best opportunities to do this is with images of prisoners employing their time in job placements, self-growth programmes and/or restorative justice & community education projects.

A Cedar Creek inmate and researcher in the Prison Moss Project studies mosses. Credit: Nalini Nadkarni of Evergreen State College

The Prison Moss Project, part of the Washington Department of Corrections‘ sustainability efforts uses prisoners time for the benefit of multiple causes. The project studies the growth of different mosses, cultivates the fastest growing species and sells them commercially as an alternative to mosses stripped from America’s temperate rain forests. Harvested mosses constitute a $265 million/year business. 90% of mosses come from Pacific Northwest forests. The majority of mosses are used for short lived floral-arrangement. Moss can take between 20 to 40 years to regrow even a small patch of a few square feet.

The beauty of this model based on simple scientific observation and applied methods is that it is replicable the world over. And, the business that results makes sense too.

A Cedar Creek inmate and researcher in the Moss-in-Prisons project tends the garden. Credit: Nalini Nadkarni

So, the benefits? First and foremost, the inmates at Cedar Creek, a minimum security facility in the rural southwest of Washington enjoy daily active learning. Prison staff have described the facility as one without idle time among its inmate population. Engaging the bodies and minds of frequently docile populations is the first step in combating recidivism.

Concurrently, tax-payers (economically-efficient prisons), tourists (untouched old growth forests) and global citizens (robust ecological legacies) all benefit too. Finally, all this pales in comparison to the rewards for the Pacific Northwest old growth forests, which in future will not suffer unsustainable tree-stripping and moss harvesting.

A Cedar Creek inmate and researcher in the Prison Moss Project in the purpose built greenhouses. Credit: Nalini Nadkarni

How did all this start? Two convergent forces came together. The first was a general move by the Washington Department of Corrections to improve its carbon footprint, sustainability and opportunities for its inmates. This involved composting, recycling, organic farming, beekeeping at selected facilities. This green awakening fell into step with Nalini Nadkarni‘s need for extended and immediate research into moss varietal growth patterns.

Nadkarni has been called the “Queen of the Forest Canopies”. I am not one for personality worship, but let’s just say her work is socially – as well as environmentally – responsible, she knows how to work media channels, her message is imperative and the Evergreen State College in Olympia is very lucky to have her on faculty. She co-founded the Research Ambassador Program at Evergreen, which seeks to combine academic and non-academic practitioners to widen the reach of environmental dialogue and deliver relevant forms of communication to different groups; from inner city youth, to business CEOs.

It’s all about respectful communication, and it’s all for the benefit of our environmental futures.

Daniel Travatte, 36, suits up to check on the Italian honey bees he cares for at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest, Wash. on Friday, Oct. 17, 2008. The bees are part of a program to help the prison be more environmentally green. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

Inmate, Daniel Travatte, tends the Italian honey bees he cares for at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest, WA. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

The media coverage of this programme has often focused on the story of a young inmate who, since release, secured a biochemistry PhD full ride scholarship at the University of Nevada, Reno. He was imprisoned after accidentally killing his friend with his sports rifle in his student apartment. Four years later, he has continued the exceptional academic track he seemed destined to follow. It is a testament to the Washington Department of Corrections and Nalini Nadkarni (his mentor during time served) that his life has been delayed rather than destroyed.

But, he surely is an atypical case and it is a case that obscures the facts about the sustainable projects in operation at Cedar Creek. Not every inmate is a PhD candidate, but every inmate is a willing recipient of education – especially environmental education which, in many cases, is totally novel. Environmental education carries an almost redemptive message in that your actions can directly benefit everyone in modest but crucial ways. Actions based upon this new learning can be very therapeutic. Responsibility for oneself and other human beings is not separate from responsibility for our shared environment.

Inmates Robert Day (left) and Brian Deboer (right) check on plants in one of the organic gardens at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest, Washington, on Friday. The minimum-security prison has adopted many environmental and cost saving practices. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

I have discussed sustainability efforts in California’s prison system before. In closing I’d like to repeat the sentiments of Cedar Creek superintendents who, in attempts to convince the public of the utility of this program, talk of the direct reduction in operating costs at the facility. If commentators such as myself want to espouse the rehabilitative value also then so be it. Doubters now have firm fiscal, quantitative evidence – in addition to qualitative inmate testimonies – to shape their support for sustainability programmes in prisons. WDC senior staff are adamant Cedar Creek is the correctional model to follow in the 21st century.

Inmate Robert Knowles pitches plant stalks into a compost pile Oct. 17 at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest Washington. The minimum-security prison has adopted many environmental and cost-saving practices. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

There are many resources out there on the Prison Moss Project and Nalini Nadkarni‘s ongoing evangelism. I personally would recommend in this order … Nalini Nadkarni’s recent TED presentation about the opportunities for academic & non-academic communities to unite for greater good; this extended video from KCTS (9 minutes); this interview with Nadkarni; a recent Mother Jones summary of her projects and two media reports (1), (2).