You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

A temporary gig as a set photographer took Jordana Hall to San Quentin State Prison; her heart and consciousness propelled countless return visits. She has worked particularly closely with men who were convicted when juvenile (under 18) and were sentenced to life in prison.

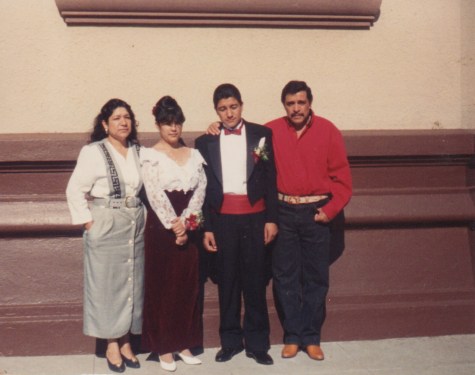

Hall has worked as a volunteer in existing programs; launched her own project that melds poetry, family letters, snapshots and her own portraits; and visited the hometowns and families of prisoners. The ongoing body of work Home Is Not Here is part of Hall’s senior thesis exhibition. It will be on show – beginning April 2013 – at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

I wanted to learn more about Hall’s motives and discoveries.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Prison Photography (PP): How did you get access to San Quentin State Prison?

Jordana Hall (JH): My work at San Quentin started in June 2011. I was hired as the set photographer for a documentary (working title, Crying Sideways) by SugarBeets Productions. The documentary details the stories of a group inside San Quentin called KIDCAT (Kids Creating Awareness Together).

PP: KIDCAT is a group of lifers sentenced as juveniles, correct?

JH: Yes, you can follow KIDCAT on Facebook.

PP: They describe themselves as “men who grew up in prison and as a group have matured into a community that cares for others, is responsible to others, and accountable for their own actions.”

JH: I began attending KIDCAT’s bi-weekly group meetings as a volunteer. During this period of volunteering, I developed a working relationship with the members of KIDCAT. Showing up when I said I would, being accountable, and most of all keeping an open mind and heart while inside re-assured the men of KIDCAT that I was a trustworthy member.

Then in June 2012, I started working on my senior thesis for my Photojournalism BFA at the Corcoran College of Art and Design. I approached Lieutenant Sam Robinson, Public Information Officer at San Quentin, with the idea of starting the “Home Is Not Here” project. If I had not had the relationship that I do with the men of KIDCAT, Sam would not have been so willing to help. It really is this relationship that I have with the group that has allowed me so many opportunities to continue my work there. I’ve been going into San Quentin for a year and a half now, and have only been able to bring my camera three times.

To be granted access to San Quentin – even minimal access – requires a lot of work. There needs to be a legitimate return for the prison community. In my case, publishing my work to Young Photographer’s Alliance, posting to my website, and eventually in an exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art was enough justification for the prison to allow me to continue working inside.

I never take my access for granted.

There are strict rules about what you can and cannot do, wear and say. If I slip up – even just a little – my access is on the line.

PP: Why did you take on the project?

JH: After hearing the inmate’s stories during the documentary filming, I realized that all of them were just teenagers who were dealt a bad hand. This is not to say they don’t take responsibility for what they did. They definitely do. Their stories resonated to my core; the stories would impact anyone who heard them. I left the prison gates that day realizing that they could be my brother, father, or best friend. I began to think about their families. Most of the men in the group are in their mid-thirties; they have spent more than half of their lives in prison. I thought about how they struggle to keep working relationships with their loved ones for so many years through the prison walls. That wondering led me to my senior thesis project.

Home Is Not Here documents the relationships between an incarcerated person and his family. I seek out the ways in which their relationship can be kept when there are so many barriers involved.

PP: What have you learnt?

JH: I’ve learned that the families of incarcerated people are the least documented victims of crime. Communities shun them for “raising a criminal.” There are limited resources available for them to get help. These families mourn the loss of their loved one’s free life with little to no support.

I learned the truth in the statement, “When one person is incarcerated, at least five people ‘serve the time’ with them.” I have seen family members go about their daily lives with a piece of their heart locked away in prison.

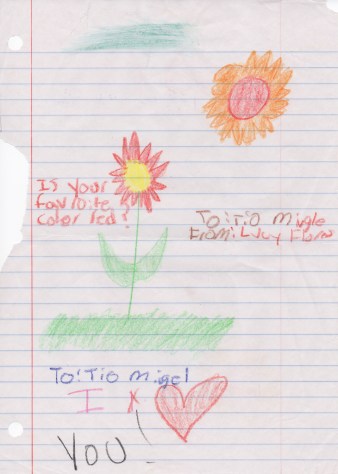

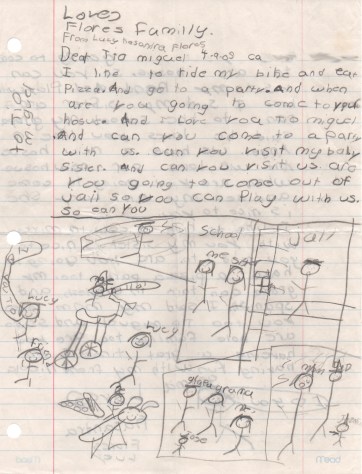

JH: I learned that letters from a child to their “Tio Miguel” (who they have never met outside of prison visitations) would break your heart. I learned that even the toughest looking men still get tears in their eyes when you ask about their family.

I am still learning.

PP: What did the prisoners think of being photographed?

JH: The first day they were most interested in seeing how a digital camera works. I am very hands-on with my subjects, and with the permission of Lt. Sam Robinson, I handed my second camera body to the guys to play with on the breaks during filming. It was both funny as well as saddening to watch their amazement at the foreign device.

The first time I went in, I asked to see an inmate’s cell. The guys all looked at each other, waiting for someone to volunteer. One by one they denied my request to see their space. We ended up going to a stranger’s cell, just so I could poke my head in from the door. Soon after, I fully realized the shame that comes over them when asked about their cells. It is the only space that is their own, but it also the cage they are locked in at night. These 6 x 12 cement cages are a place both of safety and of degradation.

After I stuck around for a year, I approached the cell situation, again. This time they were excited to show me their space. Their family photos on the wall, bookshelf with notebooks, sketchbooks, and wall markings left from previous inmates. “Stay Focused” was scrawled into the yellowed paint next to the metal bunk. It took some time and a lot of trust building for me to get on that level with them.

PP: Did you give the men prints?

JH: Giving the guys the prints is absolutely one of my favorite parts!

The Home Is Not Here project had me traveling to the hometowns of three men. I went with only small clues of what and where to photograph – “The Dairy Queen where I took my first girlfriend on my first date,” or “The restaurant named after the city in Vietnam where my family was from.”

When I brought back prints from my trips, the guys were blown away by how much had changed, and how much had stayed the same.

I was asked by one inmate to visit the grave of his grandmother. They were extremely close and she passed away while he was in prison. When he saw the photograph I took there, he began to cry. It was almost as if I had delivered him a physical place to grieve her passing.

I try to give back to my subjects as much as I can. I try not to be that photographer that comes in, gets the story, and never comes back. They give so much of themselves when they allow me to photograph them, giving prints to them is the least I can do.

PP: What did the staff think of being photographed?

JH: I never photographed the staff, although some day I hope to see some really thorough work done about the people who work in prisons. It would be a fascinating story.

PP: I agree. I’ve yet to see a photography project that suitably deals sympathetically and deeply the complex and stressful dynamics of correctional officers’ work and lives.

PP: Could photography serve a rehabilitative role, if used in a workshop format in prisons?

JH: I think a workshop on photography in a prison would be an incredible idea. These men are so introspective and have so much to offer, creatively. The documentation of life inside prison by an inmate could offer such insight for us all.

PP: Are prisoners invisible?

JH: Yes, I believe prisoners are invisible. Everything about the prison system is set up for them to be invisible, and stay invisible. To be silenced, and out of sight. What I aim to do with this project is to shed some light on a piece of an inmate’s life that is not seen. When people think prison photography they think of hardened criminals, drug addicts, grimy hands gripping cell door bars, and the underbelly of society. I am offering the alternative viewpoint, which is the humanity inside. These men are fathers, sons, brothers, friends, and they all have people who care about them. They also have built communities of support for each other, inside.

PP: What’s been the feedback to your the work?

JH: As I work I like to get feedback from my peers. A lot of people who see photographs of inmates and due to their preconceived notions will shake their head and walk away thinking, “What monsters…” but with the work I do, I try to side step this notion and say, “No, look closer.”

No matter what I do, some people will never see it the way I’d like them to, but for people who can be open-minded, the work gives an inside look to the humanity that exists inside prison, and awareness of the struggles of their families.

PP: Anything else you’d like to add?

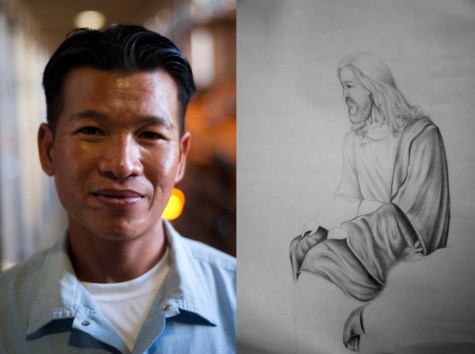

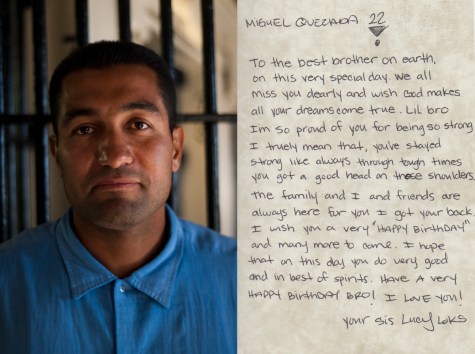

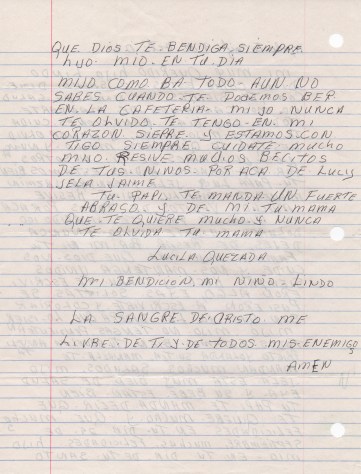

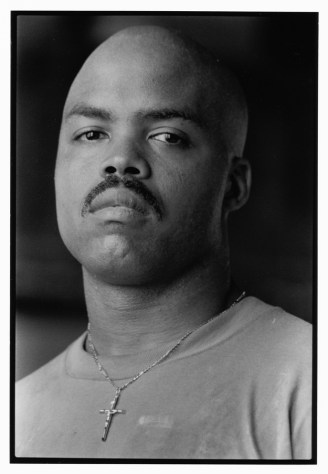

JH: As I move forward in my thesis, I am turning my focus to just one inmate in particular, Miguel Quezada. This is the working statement:

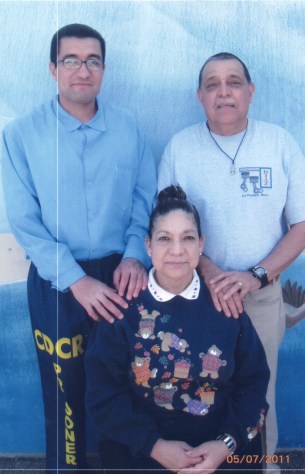

“Estamos Contigo (We Are With You)” – Miguel Quezada (below) was incarcerated at age 16. Now 31, he has spent half of his entire life in prison. Due to a harsh judicial decision that he should serve his sentences consecutively, his first parole hearing is not until the year 2040. He will be 60 years old. Home, for Miguel, rests between the realities of life at San Quentin Prison today, memories of his childhood cut short, and dreams of a faraway tomorrow. His family shares this stress, mourning the loss of their loved one’s free life. From the part of South Modesto, California known for its lack of sidewalks and high crime rate, Miguel grew up in poverty with his parents who immigrated from Mexico. His mother and father, Arturo and Lucila, are almost completely illiterate, so writing letters takes a lot of time and energy. Miguel appreciates it when they do write, but loves when they send photographs. His nieces and nephew, who he has never met outside of prison visitations, write him frequently and give him a sense of connectivity to the outside world. Miguel is one of hundreds of men in the state of California with similar stories – serving life for a mistake made as a teenager. The barriers of the prison walls will never restrain the emotional longing of one human being to be with another.

PP: We look forward to checking in again soon. Thanks, Jordana.

JH: Thank you.

© Dave Jordano

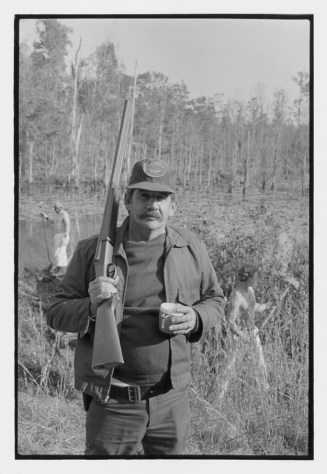

Dave Jordano responded to yesterday’s question Have you ever seen prisoners on your daily commute or holiday road-trips? with the above image.

It shows prison workers maintaining the levee along the Mississippi River in southern Illinois. It is his only photograph of prisoners.

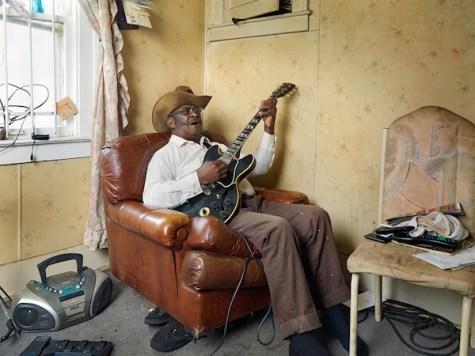

Dave and I had been in recent contact because I’d interviewed him for Wired.com and featured HIS AMAZING PHOTOS OF DETROITERS, including the one of Glemie below.

I write:

Unbroken Down is an attempt to set the photographic record straight. Jordano believes that Detroit is more than a tale of decline and images of the associated urban decay. Yet, a lot of celebrated photography projects made in Detroit recently have focused on ruination as if the apocalypse passed through and kept going.

“Detroit is still a living city. Why hasn’t this been part of the equation?” asks Jordano of most photographic output.

Please check out Captivating Photos of Detroit Delve Deep to Reveal a Beautiful, Struggling City. Many have enjoyed it; I am sure you will too.

© Dave Jordano Glemie, Westside, 2011.

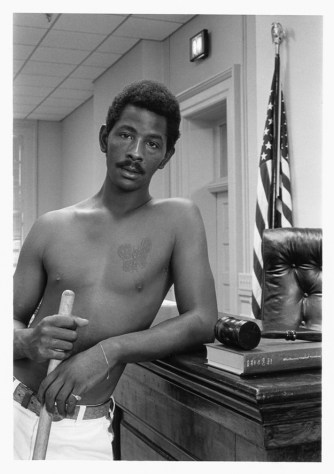

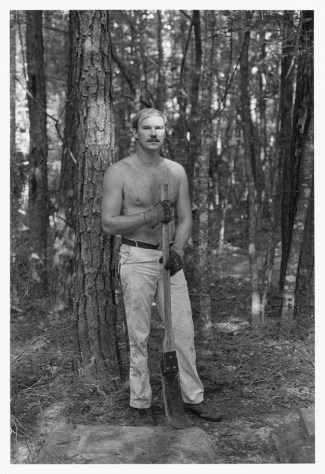

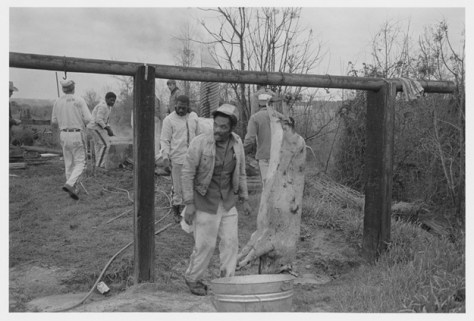

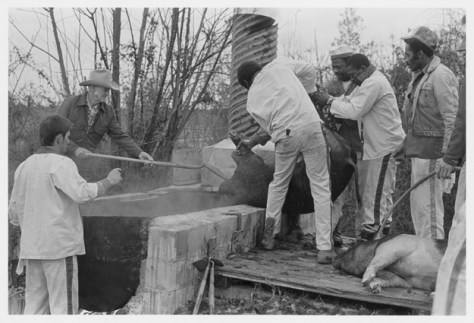

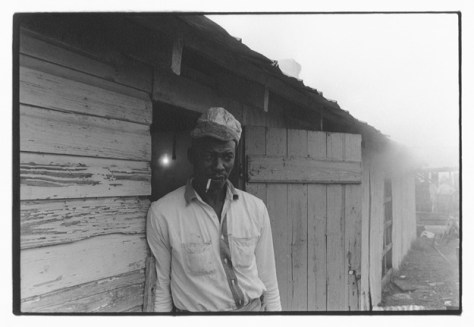

Prisoner at the County Farm, making cane syrup, 1966.

The Center for Documentary Studies described Paul Kwilecki (1928-2009) as “perhaps the most important late-twentieth-century photographer you’ve heard little to nothing about.” His work is completely new to me. Thanks to Mark Peter Drolet for the tip.

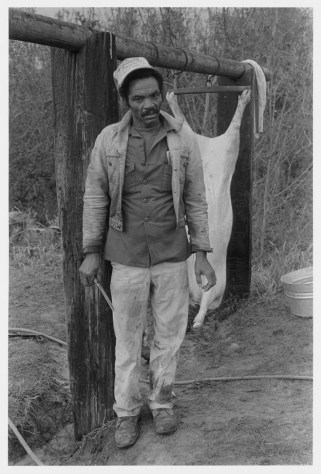

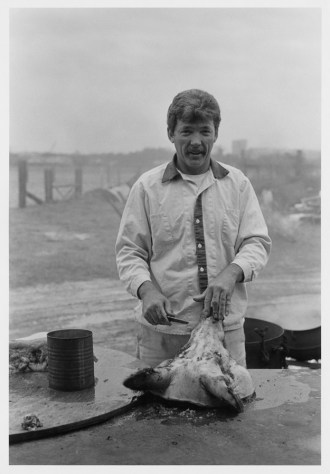

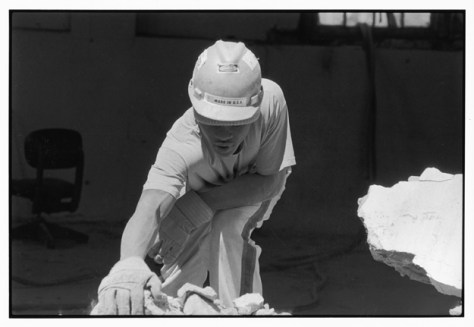

What I so fascinating about Kwilecki’s photographs is that they focus on the work details to which prisoners were assigned, ranging from 1966 to 1998. I don’t want to get into a debate here about the degree to which the work Kwilecki photographed was rehabilitative – it would be pure speculation. Instead, I’d ask you to muse on the changing nature of the work – cane syrup production; irrigation ditch digging; courthouse janitorial work; brush-clearing; hog butchering; and construction and renovation work, again in the courthouse.

Before the era of mass incarceration it was common for prisons to have their own pasture, cattle, milk parlours, arable land, and year-round crops. The organic foods produced by prisoners were sometimes sold outside the prison, but also almost always consumed by the prisoners themselves. Why is this no longer the case?

In the eighties, when inmate populations soared and with them prison budgets, cost cutting took its grip. Farms and work details only remained if they drew immediate profits (or, were at the very least, not money-losers). The staff costs to supervise self-sustaining food production were not deemed worthwhile. I’m sure arguments about security factored in somewhere too.

Added to this was a philosophy that rehabilitation was a flawed prospect and the only thing to do with prisoners was to “incapacitate them”, This is why, today, prisons don’t have their own cattle, but they do press license plates.

In short, as the U.S. prison population rocketed to 2.3 million, contracting of services became big business. Prisoners ended up with overcrowded cellblocks, less time in programs, more time in lockdown, sub-standards foods and jobs that supported the production of State essentials such as uniforms, furniture and ironically industrially-manufactured foodstuffs. Prisoners have made products for IBM, Starbucks, Walmart, Microsoft and Dell.

Aside of this brief history of prison labour – and returning to Kwilecki’s photography – what is also refreshing to see is the relaxed and purposeful interactions between prisoners and guards. People might be shocked to see images of prisoners using butchering knives, but on a daily basis, U.S. prisoners are using tools for sophisticated fabrication work. Unfortunately, we often only hear about the use of tools when they are shanks.

One final note. This is the only collection of images I have encountered of prisoners butchering hogs. Unique.

The Center For Documentary Studies at Duke has a 634 image archive of Kwilecki’s work and his life’s papers and contact sheets too. Enjoy discovering Kwilecki’s work as I have.

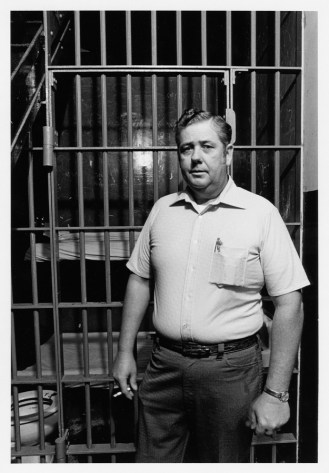

Sheriff Shorty (E.W.) Phillips in front of one of the women’s cells, [circa 1972].

Prisoners and guard working on dam, 1979.

Prisoner cleaning court room, 1979 Sept.

Prisoner with a bush hook cleaning Darsay family cemetery in the southern part of the county, 1983 June.

Hog killing at the County Farm, 1983 Mar.

Hog killing at the County Farm, 1983 Mar.

Hog killing at the County Farm, 1983 Mar.

Hog killing at the County Farm, 1983 Mar.

Butchering hogs, County Farm (prison), 1983 Mar.

Prisoner at the county farm butchering hogs (prison), 1983 Mar.

Prisoner at the county farm (prison) butchering hogs, 1983 Mar.

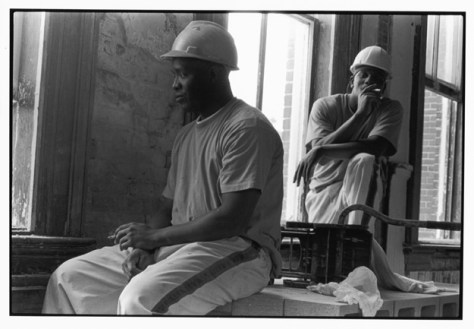

Prisoner doing construction work, 1998 Apr.

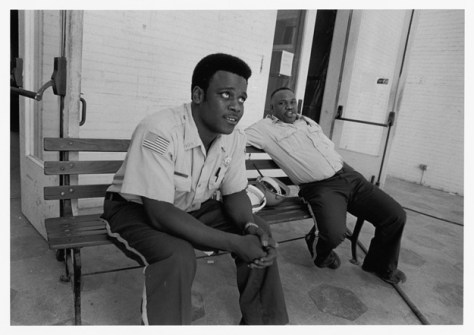

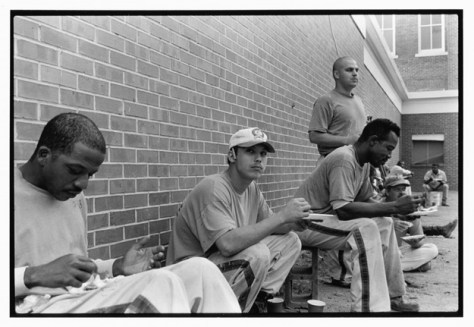

Prisoners on break from construction work, 1998 Apr.

Guards, 1998 Apr.

Prisoner, 1998 July.

Thanksgiving dinner on courthouse grounds, 1998 Dec.

Neve Tirza, which houses 180 women, is Israel’s only women’s prison. In 2011, Tomer Ifrah, a photographer based in Tel Aviv, spent one day a week for three months photographing life inside. Ifrah’s series is Women’s Prison.

“The prisoners come from diverse social backgrounds, and mostly who belong to powerless minorities,” says Ifrah in his artist statement. “They must share their lives in close quarters. Most women in Neve Tirza Prison are serving their second or third terms there, trapped in a vicious cycle.”

Ifrah says that the relationships between the prisoners, the staff and he were rooted in mutual respect and trust. Cursory Google searches of Neve Tirza Prison reveals a history of abuse from 10 years ago; in particular threats to Palestinian prisoners; a recent influx of white collar criminals; and ongoing inhumane allotment of physical space. Neve Tirza has falsely been cast as a “paradise” by American TV. Conditions, on the evidence of our conversation, have since improved significantly.

Scroll down for the Q&A. Right click any image for a larger view.

Prison Photography (PP): Tell me about how you got access to Neve Tirza Prison.

Tomer Ifrah (TI): Going into the prison was such a lucky thing – even to get access for one day. I was sent by a local Israeli women’s magazine to photograph a single prisoner. I went to the prison with a reporter.

I had to wait for the reporter to do the interview, so they kept me in one of the segments of the prison. Of the five segments, I was waiting in the “easiest” one – the one in which you are kept if you have good behavior or committed minor crimes. I could talk with the prisoners quite openly.

I realized there was something in Neve Tirza for a project. I was quite skeptical [at the chances of doing a project] but I found out who was in charge and knocked on the door of the manager of the prison. I told her that I was interested in doing a project and she said immediately that it sounded good. After a few days and a few phone calls, I got in.

In the beginning, they didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do; it was the first time someone had go in and photograph the prisoners. They didn’t know exactly what to tell me. I wanted to go a few times a week, but they told me I could go in once a week.

PP: Neve Tirza is the only women’s prison in Israel. What’s the population of Israel?

TI: More than 7.5 million, perhaps 8 million.

PP: Just a single prison for women from such a large population seems incredible.

TI: What are the figures of incarceration in America?

PP: There are more than 200,000 women incarcerated in America. There are 2.3 million American prisoners in total.

TI: In Israel, there are 25,000 men in prison. Approximately, 13,000 or 14,000 are criminals. The remainder are incarcerated on security related issues – mostly Palestinians.

I watched a documentary by a woman who wrote a book about Neve Tirza. After she researched the topic, she was asked, ‘Why is there such a small number of female prisoners?’ She didn’t have a scientific answer, but she noted that it was the only women’s jail in Israel and so, maybe, they fit the prisoners into the space that they have. If you don’t have a place to keep female prisoners, perhaps they convict them less? I’m not sure, but this was the only answer I have found.

PP: On your website, I didn’t see text or information accompanying the images. What’s the main story in Women’s Prison?

TI: This project was made exactly at the time I got involved with Frames Of Reality, a project that is a partnership between Palestinian photographers and Israeli photographers. Each of the photographers could choose a subject, so I chose the prison.

While I was working on Women’s Prison, I came with new images to the group and each week professional photographers saw them. The main thing that came out of our discussion of the images was that Women’s Prison is about feelings, about sensations, about the prisoners and what they go through. I was photographing emotions.

PP: And what were the overriding emotions?

TI: Neve Tirza is a very difficult place to be. It is a very intense place. The atmosphere is not easy. It’s so small.

TI: Neve Tirza is very crowded compared to other jails in which each prisoner has his or her own cell. The women are kept six to a cell in some of the segments. Just imagine going into a very small cell and you have to live with five others? Most of the time – from 7pm until morning – the doors are closed. Outside of those times, you can go outside, but even then it is very crowded. Imagine the conflicts between prisoners in such a small place?

PP: Conflicts? Was it a violent place or was it pressurized?

TI: I can imagine that sometimes it comes to physical violence but I think that mostly it stays at the level of shouting and verbal abuse. But there’s the other side of it; if you stay close to someone for a long period of time, very strong bonds develop. There is lots of caring and love among the prisoners. It feels like a very close family.

PP: Because there’s so few prisoners, I must assume that the women have been convicted of serious crimes? And they come from diverse social backgrounds?

Most of the women are convicted for drugs issues, caught in a cycle. Most women were serving their second or third term. They don’t have any options when they are released. I think this is a universal fact, not just here in Israel.

PP: What do the women who are trapped in this cycle, as you describe it, think of prison? Is it an opportunity to rehabilitate?

TI: It goes both ways. The staff and the manageress are doing their best to help them; you can see it in their interactions. They treat them the best they can. The administration has the best intentions. But on the other hand, it is hopeless, because they don’t feel that they can ultimately help them.

There also is a lot of criticism because most of the people in Neve Tirza are not supposed to be in jail; they are supposed to be in psychiatric hospitals, possibly. When you’re inside there you understand that immediately. A big percentage of the women have mental disorders. If you put people who are unhealthy in their minds together it can be hell for them.

My personal opinion about it is that it doesn’t help anybody. The system must be changed if you want to really help them and not just lock them up away from society. If you really want to help them there are other ways to do it.

PP: What did the women think of you and your camera?

I was surprised. Some of them at first told me that they weren’t interested in being photographed, but there were very few. For the whole period of time, I respected that and didn’t photograph them.

The women I did photograph felt very comfortable being photographed or didn’t give it any special attention. For me, it was excellent because I could document as I wanted.

PP: Did they ask what you’d do with the pictures?

TI: Yes. I told them they were going to an exhibition by Frames Of Reality (the Palestinian/Israeli photographer project) and that it would probably publish in magazines. They were okay with that.

The bigger thing was to get the approval of the warden. She was more difficult [to satisfy] than the prisoners. There were some photographs she didn’t allow to be published.

PP: What photographs did the administration censor?

Photographs that they felt that the families of the victims would be hurt by. If I showed a prisoner sentenced to murder, it would cause difficulties as that a very sensitive issue with the family of the victim.

PP: What I find is quite common in American prison photography projects is there are different levels of complicity and expectations between the prisoners and the staff. And also there can be different motivations for inclusion in – and accommodation of – a photo project between the management of a prison and the staff of the prison.

TI: In the beginning I was helped by both management and staff. Towards the final stages of the project they felt they were taking a chance with me, and with my security. They were worried I might get hurt. They probably have a good sense about what’s going on there, but I felt it only in the final stages.

I feel I didn’t have enough time to photograph the project as I wanted. Even with several hours a week, many things could get in the way. I could lose hours of time making photographs if there was something going on in the prison [that restricted my access]. I can often feel that way with projects, but particularly this one. I said thank you for every minute I had to photograph but still …

PP: Do you know of other photographers who’ve photographed Israeli women in prison?

TI: I only know of one student. It was done well, but not a full body of work. The photographer probably didn’t have much time inside.

PP: Magnum photos has a single lonely image made by Micha Bar Am from 1969.

PP: Is Neve Tirza Prison an ignored topic?

TI: No, no. Everybody wants to get access. I was very lucky. I think if I’d asked six months before I wouldn’t have got access. It was perfect timing. They felt comfortable with me and they trusted me. I wanted to return that trust so every image that I photographed I immediately showed them. I was very honest with them.

The thing that helped me to photograph there most was the fact that the prisoners trusted me. They understood that I would not take pictures that they did not want me to take; I would publish it in an an honest way.

PP: Obviously, a lot of imagery that comes out of the Israel/Palestine region is politicized. I’ve seen some work of Palestinian political prisoners. How does your body of work fit into that visual territory?

TI: I was not allowed to photograph the Palestinian female prisoners, of whom there were very few in Neve Tirza. If it were to cause problems for the prison staff, I was happy to not do that.

PP: Why were you not permitted to photograph Palestinian prisoners?

TI: There is a single image of an Arabic woman praying in her cell. She gave me permission as did the prison. It was okay with her but in one or two cases it was not allowed. The modesty in Arab culture is more strict. If it is men, it is usually okay, but if it is women it is more problematic.

There are many minorities in prison. In my images, you’ll see that many women are not Israeli born. Some of them are from Russia, or Ethiopia, or South America.

PP: Is that because minorities are generally marginalized in Israeli society?

TI: Exactly. I think this is also common in societies other countries.

PP: How many images did you make in total?

TI: I was photographing with medium format film. I made about 500 images in total.

PP: Tell me about Frames Of Reality, the joint Israeli/Palestinian photography project in which you are involved.

TI: Frames Of Reality is in its third year. The meetings are held in Beit Jala, a place near Jerusalem that is easy for both Israeli and Palestinians photographers to get to. We meet once a week with guest photographers or lecturers. It is financed by another country … I don’t know which. At the end of each year Frames Of Reality has a big exhibition and publishes a book.

PP: There’s many good photographers! Dan Balilty, Ahikam Seri, Eman Mohammed, Noah Ben Shalom.

TI: I’m not surprised people know Israeli photographers because the region is such a strong place to make photos.

PP: Specifically with Frames Of Reality, you’re trying to lead by example? Does photography have role to play in bringing different communities together.

TI: I just returned form the Israeli press contest where I saw all the core issues in the photographs – from photographs of East Jerusalem to Palestinian photographers working in Tel Aviv. Photography has role but I don’t know how much influence it has.

PP: Well, I encourage editors to get in touch so your photography can be seen. Thank you, Tomer.

TI: Thanks Pete.

It was great to see Obama take on a liberal agenda yesterday with promises in his inauguration speech to improve equality for gays and lesbians and to reform immigration policy.

On the topic of immigration, or more precisely one arm of immigration – refugees and asylum seekers fleeing political or religious persecution – have you seen Gabriele Stabile and Juliet Linderman‘s new book Refugee Hotel?

Refugee Hotel is a collection of photography and interviews that documents the arrival of refugees in the United States. Stabile’s images are coupled with testimonies from people describing their first days in the U.S., the lives they’ve left behind, and the new communities they’ve since created.

I noticed the work as the book was in planning 18 months ago. Good, now, to see it massaging its message in people’s hands.

The press release details the following testimonies:

Psaw Wah Baw was forced to flee her village in Burma amidst armed conflict. She describes how her family left their village with just five cups of rice, beginning an arduous journey toward resettlement that would take them through Bangkok, Tokyo, Illinois, and Texas.

Pastor Noel fled the civil war in Burundi in 1972 for a refugee camp in Congo. When war erupted in Congo in 1996, Noel was once again forced from his home. He now lives in Mobile, Alabama, and is a central figure in the African refugee community as he pursues citizenship.

Felix joined the rebel army in South Sudan as a teenager but was forced to flee to a refugee camp in Kenya when fighting within the army threatened his life. After long delays and identity theft by a fellow refugee, Felix now lives in Erie, Pennsylvania, where he works for Habitat for Humanity to assist African refugees in purchasing their own homes.

Refugee Hotel is the latest project by Voice of Witness, a small San Francisco-based non-profit, founded by author Dave Eggers and physician/human rights scholar Lola Vollen.

Voice of Witness uses oral history to illuminate contemporary human rights crises in the U.S. and around the world by publishing book series that depict human rights injustices through the stories of the men and women who experience them. The Voice of Witness Education Program then takes those stories, and the issues they reflect, into high schools and impacted communities through oral history-based curricula and holistic educator support.

Published by McSweeney’s, you can buy Refugee Hotel here.

Read more about the project on FADER and Miss Rosen and TIME LightBox.

View a large PDF of the Refugee Hotel Press Release

Published by McSweeney’s, you can buy Refugee Hotel here.

A couple of months ago, I was contacted by the Magnum Foundation (MF) and asked to nominate six photographers who were pursuing projects of social importance. The MF was readying itself to disperse the 2013 Emergency Fund grants.

Today, in conjunction with TIME LightBox, the Magnum Foundation announced the 10 chosen photographers and their bodies of work:

Adam Nadel, Getting the Water Right

Alex Welsh, Home of the Brave

Giulio Piscitelli, From There to Here

Jehad Nga, Unmasking the Unthinkable

Mari Bastashevski, State Business

Olga Kravets, Radicalization

Rafal Milach, The Winners

Tanya Habjouqa, Occupied Pleasures

Philippe Dudouit, The Dynamics of Dust

Tomoko Kikuchi, The River

Two of my nominations won support. That’s a one-in-three strike rate; better than the current form of Blazers’ guard Wesley Matthews.

Nominations by myself and 14 others resulted in a pool of 100 photographers. From that 100, a three-person editorial committee – Philip Gourevitch, contributing writer for the New Yorker and former editor of Paris Review; Marc Kusnetz, former Senior Producer of NBC news and Consultant for Human Rights First; and Bob Dannin, former Editorial Director of Magnum Photos, and professor of history at Suffolk University – chose 10 projects.

10 grants have been dispersed. Regional photographers who live and work near their homes each received between $4,000 and $7,000, while the photographers working internationally secured grants between $7,500 and $12,000.

“The EF 2013 grantees are a group of talented photographers, working internationally and within their home regions. All of the projects anticipate emerging issues that are underreported and show great promise to reveal new perspectives through a range of visual styles and approaches. […] The selected projects address a range of pressing issues including human impact on one of the world’s most delicate ecosystems, systemic roots of violence in vulnerable communities, investigation of human rights abuses, and post-arab spring immigration flows,” says the Magnum Foundation.

Due to the sensitive nature of many of these projects, MF is being careful about the amount of information it shares publicly about the projects’ details and geography. We’ll just have to follow the photographers’ output closely.

Congratulations to all grantees.

See the work at TIME LightBox.

Above image: Tomoko Kikuchi, from the series The River.

Guillaume Pinon spent over a year negotiating access and photographing inside a prison in Málaga, Spain. He shot exclusively in a single wing called Module 9, in which the majority of prisoners were non-EU citizens incarcerated for drug-trafficking crimes.

Pinon undertook the project as part of his Masters degree, for which he was required to produce a book. You can view the book, Modulo 9 on Issuu.com.

“During three months I was allowed by the inmates of the Module 9 of Málaga prison, to take photographs of their daily life,” says Pinon. “This is an intimate story of what it means to be a pre-trial detainee stuck in the middle the Spanish criminal system.”

Pinon is interested in populations on the margins of society and his past work includes series on children’s disability, hospitals, gypsies, liminal spaces and religious practice. Due to the restricted nature of the prison subject, Modulo 9 was the greatest challenge Pinon has taken on. We first made contact over a year ago, but due to sensitive negotiations with the Spanish authorities we are only able to publish our conversation and Pinon’s image now.

Click any of the images for larger versions. Scroll down to read our Q&A.

PP: Why the interest in the subject?

GP: I have a great attraction towards entering spaces with very restricted access to document people living within. When I am told, “You will never be able to photograph there,” I am even more convinced about a project.

I have always come across dramatic, painful stories, which has made my activities more motivating and rewarding – as a photographer AND as a human being.

PP: Any prison photographers who’ve sparked your interest?

GP: The starting point may have been Too Much Time by Jane Evelyn Atwood.

PP: Featured in the past on Prison Photography, if I may add.

GP: As the project progressed, I looked at the portfolios of many photographers from different time periods. I watched movies and documentaries on the prison subject – two impressive examples are A Prophet by J. Audiard and Prison de Fleury, les images interdites, an Envoyé Special by France 2.

PP: The detainees in Málaga Prison are awaiting trial. Did you deliberately want to photograph in a facility that had prisoners “in limbo” and awaiting judgment?

GP: Initially, I wanted to work with three different types of prisoners; those not categorized by their legal position, but those that captured more my own interests. I wanted to explore the situation of female prisoners, the “gitanos” (gypsies), and the Maghrebian prisoners. The prison of Málaga principally incarcerates remand prisoners. It was not a deliberate choice of mine; I took what was available to me.

PP: MODULO 9 is your MA thesis project for the London College of Communications MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography. Tell us about your experiences on the MA.

GP: I am a father of two young boys. The oldest, because of his disability, requires much of the time and presence. In the circumstances, an online MA was the perfect opportunity; it suited my complex family life.

The LCC MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography taught us all the issues surrounding the moments before, during and after pressing the shutter. With this I mean to find a story, to do a research on the topic, to sort out all the administrative aspects, to approach and tell the story, to edit photographs and finally to present the completed work. I realized that photography is not only about the “click” if you want to achieve a good project.

However, nothing can replace a face-to-face conversation, even Wimba [which the class uses for class webinars and crit]. I am not sure whether I could be able to recognize Paul [Lowe] or John [Easterby] if I was in the same room! Which is a bizarre feeling. Overall, my MA has been a very beneficial and enriching experience.

PP: I was told you received a 3-month deferral for the submission of this work because of problems with access. Can you explain what happened?

GP: It is complex story, but I’ll cut it short. To be allowed to work inside of the prison came with very strict conditions. One of them was to take photographs only when I was accompanied by a nominated staff-person. However, that person had his own work to do and, therefore, could not dedicate as much time as had been initially agreed. So, in December, during a board examination where the evolution of my work was assessed, I received the extension. By that time, roughly, only the portraits had been completed.

PP: Apart from the delay, did you face any other hurdles?

GP: To work in such environment is a great and unique opportunity; however, it is very difficult, even more for a photographer with little experience like me. On many occasions I found myself upset and frustrated with the situations or the people.

I kept my mouth shut and with a smile because I was aware of how rare the opportunity was “to be inside” with the camera. Even though life inside the prison was structured on routines, each day there appeared to be a new challenge. Life was always disturbed by external and internal factors of the Modulo 9 – the mood of the guards, a newcomer to the module, a conflict, an inspection of cells, the weather. Insignificant details could have a snow ball effect within minutes.

PP: I presume each prisoner signed a model release?

GP: A signed model release from each prisoner appearing on my photographs was another unbending condition of the authorization. I eventually managed to get more than fifty signatures.

PP: What did the prisoners think of your presence and your work?

GP: I came across all kinds of reactions during the three months, from suspicion (“You’re from Interpol”) to hope (“Help me to get free”).

None of them knew that the work was part of the MA. I purposely never mentioned it thinking that I would lose some credibility.

Mostly, they asked about the reasons of me doing this work and how I was going to present the work. They didn’t like the idea of a publication in a newspaper or magazine, but on the other hand a book seemed to be a more attractive format to them.

PP: What did the staff think of your presence/your work?

GP: Again, varied reactions. Mostly, the prison authority supported the project and it is pleased with the final result. However, the staff of the Modulo 9 perceived my presence with the camera as another source of potential problems which meant more work and pressure for them. They were mainly protecting the reputation of their module and the rights of each of the prisoners. Eventually, we managed to spend the three months without a major outburst and occasionally I did receive unexpected help.

PP: Your photographs depict a stark but violence-free environment. Is this the reality in Málaga Prison?

GP: My photographs only document the daily reality of the Modulo 9. The prison of Málaga is divided into 14 modules. Each of them has its own type of prisoners – foreigners, females, youth, Muslims, remand-prisoners. Therefore each module has its own routine, problems and activities.

I can only share what I experienced within Module 9, which has greatly improved in recent years. Improvements have come about for two main reasons: first, the willingness of some staff to improve the quality of life inside of the module and, second, the fact that the majority of the prisoners now are Muslim.

Because of the Islamic faith, you sense great respect between prisoners. Moreover, most of them are in jail for the same reason (drug-trafficking), and they’re under the same conditions (no family living in Spain, no money, no friends, no knowledge of the language). They try to help each other.

Nevertheless, as a module of remand prisoners, the population changes quickly and therefore an established but fragile stability can be quickly jeopardized. During my last visit, a year later, I barely knew the prisoners. Talking to some of them and looking around, I could feel a change; Modulo 9 was not the same any longer, and may be not have been for the best.

PP: What are the attitudes of Málagans and Spanairds generally toward prisons?

GP: Sometimes, the Málagueños are like me; life inside of a prison creates a sense of curiosity. They want to know if what they see on TV is the same in the reality. However, at present, there are other overruling problems, such as the current financial crisis, which take all the attention. As a consequence, the situation in prisons is generally ignored.

PP: Why photograph in black and white?

GP: I have always felt more comfortable photographing in black and white. To think about colour in the process of taking a picture it is not yet an instinct I have. It generally distracts me from the subject.

PP: It is a large book with a diversity of images. Tell us about your editing choices.

GP: I have mixed feelings about editing. On the one hand, I enjoy the process of selecting and playing with the photographs in order to tell the story. But on the other hand, the process relies too much on my mood of the day. It is very difficult, for me, to come up with a pragmatic selection and order the pictures in the ways I have seen great professionals do.

Módulo9 was my first experience editing. Throughout the process I regularly shared privileged conversations and received very useful comments from Paul Lowe (course director) and Ed Kashi (project tutor).

I ended up with two edits. The first, used a geographical and linear approach – the buildings of the prison, the corridors, the access to the module and finally inside of the module.

The second, which was presented as the final result, was elaborated with the support of Chema Conesa, a Spanish photographer and editor. It no longer focused on location but more on the emotions of being confined in a hostile environment where it is difficult to keep contact with reality.

Common to both editions were the double pages with the portraits and the separate chapter focusing on the story of Mouhcine.

PP: Why follow Mouhcine? Why did he stand out?

GP: Throughout the first month, each morning was dedicated to interviewing inmates. The first recorded conversation with Mouhcine lasted around 35 minutes. Only after just 11 minutes, asking him about his first night in the prison, he could not control his emotions and broke down into tears. I suggested having a break for him to recover.

By the end of the interview, I became conscious of his sensibility and his eagerness to share with me. So our relationship, day after day, conversation after conversation, grew into something more personal. On some occasions, I felt concerned about leaving him alone being aware of how depressed he was.

Apart from being deeply tragic, Mouhcine’s story emerged to be, on some aspects, optimistic. His faith in God and his willingness to learn Spanish, to work, to be involved with the life of the module helped him to handle the daily challenges of the prison. I felt privileged to be allowed to witness, share and document those moments.

PP: What do you hope your photographic study of Málaga Prison will achieve?

GP: At the beginning of the project, my only hope was to get a good grade for the MA!

Now, after showing the photographs, listening to people’s comments and with a higher confidence in the work, my plan is to go back to the prison of Málaga. This time I would focus on the female module. I’d change the concept and aim for a deeper involvement with the prisoners. And then, taking into account the best options, I hope initially to diffuse the work in and around Málaga.

PP: Final thoughts?

My intention has never been to criticize the prison system. Though, from my short experience into “the remand prisoner world” and having interviewed magistrates dealing with criminal cases, some suggestions should be made in order to improve the conditions.

I want the viewer, after looking at the photographs, to go home keeping in mind the feelings of being restricted in harsh conditions. I want the viewer to sense what it means being a remand prisoner, with his fears and anxiety, inside of Module 9.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Thanks to Ciara Leeming for the tip.

I’m intrigued by Nathalie Mohadjer‘s project Zwei Bier Für Haiti. I hope you will be too. First, you’ll need to get past the idea that Zwei Bier Für Haiti is about, or in benefit for, Haiti. It is, in fact, a body of work about the residents of a homeless shelter in Weimar, Germany. Mohadjer made the images between 2006 and 2010. She explains the title:

“When an earthquake shook Haiti in January 2010, Margitta, one of the inhabitants, started a fund-raising campaign among her neighbors in the homeless shelter, which she called “Two Beers for Haiti.” The idea was for every resident to drink two beers less a day. She collected a total of 15 euros.”

I’m always intrigued by long-term photo studies of institutions on the margins and those within them – Peter Hoffman’s Bryan House and Maja Daniel’s Into Oblivion are two top-notch examples. Mohadjer’s Zwei Bier Für Haiti/Two Beers For Haiti fires the same visual intrigues. Good stuff.

Mohadjer has nine days left on her crowdfunding effort for the book. It’ll be published by Kehrer Verlag regardless but every penny donated will be a penny less out of her pocket. See the crowdfunding page here and the video-pitch on vimeo here.

EXHIBITIONS

Works by Nathalie go on show today at the Museum Sala Galatea, Cordoba, Spain (January 16 – February 24, 2013) and works from Zwei Bier Für Haiti go on show at the Heussenstamm Gallery Frankfurt, Germany for the Abisag Tüllmann Prize Exhibition (February 19 -Mars 15, 2013).