You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

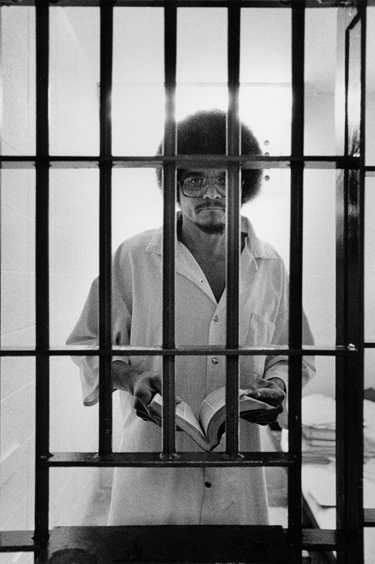

Between 2002 and 2003, New York based photographer Serge J-F. Levy, visited six maximum security prisons across multiple states. The series is called Religion in Prisons.

I am decidedly ambivalent about the role of religion within prisons – it can be a force for good and for positive change, but it can also be reductive in scope and used for manipulation. I wanted to ask Serge a few questions to see if he could help me, and us, through some of the issues and interactions religions bring about in prison environments.

Q&A

Prison Photography: Tell us about your approach.

Serge J-F. Levy: When I did the project, I did my best to approach each individual (inmate) tabula rasa. I did everything within my power to try and understand who they were in the moment I met them and to understand who they wanted to be from that moment onward. In most cases I did not know what each person was punished for.

Though I feel a general compassion for humanity and a desire to understand troubled people, I also understand that the acts of many of the people I photographed often had dire and unimaginable consequences on the lives of their victims and the victim’s families. So, my compassion and understanding is measured with an awareness of the distinct nature of my relationship to my subjects.

It seems like you’ve been to a few states. Which prisons have you photographed in and in what time period?

I started in Greenhaven Maximum Security in New York State. I went on to photograph at the Muncy Women’s Unit in Pennsylvania, MCF (Minnesota Correctional Facility) – Stillwater, MCF-Oak Park Heights Super Maximum, MCF- St. Cloud, and Angola in Louisiana.

What attracted you to prisons and specifically religion in prisons?

When an accused criminal is locked away, we, as a country and a society, have assumed the inmate will be experiencing some degree of “rehabilitation.” Instead, it would appear these environments quite often breed further damage, dysfunction, and pathology. I became interested in how inmates used their time to pursue a form of healing outside of the prescribed forms of daily routine. Through religious communities, inmates were often seeking a form of spiritual rehabilitation. This spiritual rehabilitation often provided the inmates a way to metaphorically experience a freedom beyond the obvious confinement and constraint they experience in their present lives. Religion also provides many adherents a lasting form of reflection and cleansing to purge the remains of unresolved tragedy from their pasts. So you asked why I was attracted to this project? Because I feel the literal experience of being imprisoned, stripped of freedom, and confined in a den of thieves (and murderers, etc.), is a powerful figurative example of aspects of the more general human experience. The ability to find a way to transcend the reality of one’s current circumstances and experience a healing and freedom through the channels of spirituality and reflection… that’s a valuable tool.

How did you negotiate access? Did different DOCs react to your request differently?

I got access through the most classic technique I know of; I met someone in the mailroom who introduced me to someone who worked on the second floor who introduced me to the fourth floor and on up the chain until I had an endorsement to enter my first prison. After working in Greenhaven Maximum Security Prison for several visits, I had created a body of work that would encourage future prisons of the valuable intentions and ideas behind my work.

And related to the last question of how I got access, the work I was doing was not much of a security risk for prison administrations as I was mostly working in areas and in ways that could only make the prison system and its staff look good. However, I guess there was always the risk that I could have turned my camera in a different direction and as was the case in many instances, I was left alone with inmates long enough that I could have seen more than I was potentially supposed to. But that’s not who I am or how I work.

Any memorable interactions?

One warden in Texas suggested we grab tea and beer when I made it down. I never made it down but I was always interested in whether that was an obscure Texan custom.

Is photography a security risk for prison administrations?

I just don’t know the nuances of security well enough to weigh in on that question. I could imagine that with a particular intention, a photographer may be able to provide the necessary coverage to develop a plan, but I am mostly constructing this from my avid movie watching hobby!

Some of the services/prayer/rituals you’ve photographed seem quite involved. How much time did prisoners spend involved in religious observance? Were their other outlets available to them for self-reflection and improvement, e.g. sports, industries, education, group counseling, libraries?

I found it interesting how religion served multi-faceted functions for the inmates. On the most direct level, it was a form of spiritual cleansing and growth that would happen in services and weekly or daily gatherings and meetings in chapels and make-shift religious venues. But beyond these formal locations, religion becomes an identity and an opportunity to develop a social circle; a comparison to how gangs function in prison might be an apt comparison because as I understand it, competing religions would at times seek to sabotage the work of each other. One such case was how the baptism tank had to be replaced by a laundry cart because it would constantly develop mysterious holes at Stillwater Maximum Security Prison in Minnesota.

But religion was also practiced in the art inmates created; from sculptural effigies to paintings and drawings of religious scenes, the hobby shops and prison cells often contained quite a bit of religious memorabilia. There were several outlets for inmates to reflect and experience spirituality; the arts, group meetings of various sorts (including therapy), formal religious gatherings, one-on-one consultations with chaplains, and library hours.

Policies varied from prison to prison and in each case I would hear inmates express grievance as to the limitations that were imposed upon them. I was only there for small slices of time and generally wasn’t able to get a more holistic sense of what the greater experience was like.

What did the prisoners think of your presence?

I think the inmates respected the integrity of my stated goals and the ideas I had for my work. I also think, rightfully so, many inmates were skeptical as to my intentions and my affiliation with the media. After all, many of the people I worked with were directly featured and often intensely maligned in the media during their prosecution and processing through the judicial system.

What did the correctional officers think of your presence?

The correctional officers, were largely very helpful but also insistent upon reminding me of the omnipresent dangers. On more than one occasion I was told that a particular inmate was trying to con me into believing one story or another. I generally felt that the correctional officers had seen or heard quite a bit during their time working inside.

Were their any days and/or experiences with the prisoners that shocked, surprised or delighted you?

Kneeling in a small room for Friday Jumma with 300 Muslim inmates listening to and responding to the call of Allah Oh Akbar is something that can’t be explained but only felt. Same for a Baptist or Pentecostal service.

On one occasion, I sat in a room of 10 women gathered with a Catholic chaplain, and listened to one woman recount her experience of being raped and simultaneously attacked by a dog. Sometimes, it was more important for me to listen, feel and internalize the moment without the filter of photography.

Do you follow a creed or religion?

I don’t follow any particular religious path. I lead a life that is guided by principles that I have culled from religious practice and ideas that have resonated with me over time. My “religion” is constantly evolving. The sources behind my spirituality that I can identify are Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and many other faiths and disciplines I have encountered throughout my life.

What has been the reception to these images?

I think people like it. But due to the limited exposure these images have had, I have yet to hear strong dissenting opinions if there are any.

How do you think your images fit into the visual landscape of prisons and prisoners in America. Do they confirm or counter stereotypes or common narratives?

I am seeking to provide a record of the people practicing religion in prison. Of the work I have seen done in prisons, much of it addresses religion as a component of life inside, and therefore seems to be geared toward molding the religious component of prison life into a greater aesthetic and narrative whole.

My work is more thorough in exploring this particular [religious] angle of prison life. Of course, I could be very wrong about the full breadth of quality work done on this specific topic.

Thank you for your time Serge.

BIOGRAPHY

Serge J-F. Levy’s work is represented by Gallery 339 in Philadelphia and has been exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Schroeder Romero Gallery in Chelsea, and The Leica Gallery (New York City and Tokyo) among many other national and international solo and group exhibitions. In 2011 the Princeton University Press published a book of Serge’s photographs made during his yearlong photography fellowship at the Institute, along with essays by Institute members. Serge’s magazine photography has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Life, ESPN The Magazine, and Harper’s Magazine among others.. For over 10 years Serge has been on the faculty at the International Center of Photography in New York City where he is a seminar leader in the documentary/photojournalism program and teaches street photography, editing, portraiture, and several other courses. In addition to his street photography practice, he is an avid draftsman and painter. Serge lived in New York City for his whole life … until recently moving to the Sonoran Desert.

MORE ON RELIGION ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

Body vs. Structure: Islam in Prisons

Dustin Franz’s ‘Finding Faith’

Andrew Kaufman and the Incarcerated “Jesus Freaks”

Photog Searches for Healing on Texas’ Deathrow

Measured by any metric, Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color Blindness is a scathing and utterly contemporary critique of American laws.

Now, a crowdfunding effort wants to bring the bestseller to the airwaves.

Alexander has argued that the confluence of many new sentencing laws in recent decades has created an inescapable web of penalty, deprivation and economic traps against the poorest Americans. As we know a disproportionate number of poor Americans are black and brown. A pervasive racial bias in law, particularly Drug War legislation has hit minority groups and resulted in stark, debilitating and unjust institutional racism.

NPR set up its interview with Alexander as follows:

“Alexander argues many of the gains of the civil rights movement have been undermined by the mass incarceration of black Americans in the war on drugs. She says that although Jim Crow laws are now off the books, millions of blacks arrested for minor crimes remain marginalised and disenfranchised, trapped by a criminal justice system that has forever branded them as felons and denied them basic rights and opportunities that would allow them to become productive, law-abiding citizens.”

More here, here, here and here.

In a March OpEd for the New York Times, Alexander highlighted the story of her friend Susan Burton, a criminal justice activist and formerly incarcerated African American woman, who has suggested that defendants demand trials in order to clog up the courts system.

She’s incendiary … and she’s closer to the truth than most commentators dare to believe.

A NEW MEDIUM

Wanting to propel the message and capitalise on the unusually wide appeal of a book on criminal justice, radio documentarian Chris Moore-Backman wants to produce five radio documentaries, and to publish and promote a CD box set of the series along with a companion discussion guide.

Moore-Backman plans the following five hour long episodes for the series Bringing Down the New Jim Crow:

(1) Frat Row vs. Skid Row: The Racial/Socio-Economic Disproportionality of Drug Law Enforcement;

(2) Living with the New Jim Crow: Conversations with Loved Ones of Incarcerated Men and Women of Color;

(3) The War On Drugs: Human Rights Nightmare on Both Sides of the Border;

(4) Still At It: Veterans of the African-American Freedom Movement on the New Jim Crow;

(5) White Allyship in the Era of Mass Incarceration

KICKSTARTER

If this is something you’d like to help get off the ground and hear the product, please consider donating.

– – – –

Chris Moore-Backman is a radio documentarian, nonviolence educator/trainer, musician and father. He is based in Chico, California.

Michelle Alexander is a highly acclaimed civil rights lawyer, advocate, and legal scholar. As an associate professor of law at Stanford Law School, she directed the Civil Rights Clinic and pursued a research agenda focused on the intersection of race and criminal justice.

In 2005, Alexander won a Soros Justice Fellowship that supported the writing of The New Jim Crow and accepted a joint appointment at the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity and the Moritz College of Law at The Ohio State University. Prior to joining academia, Alexander engaged in civil rights litigation in both the private and nonprofit sector, ultimately serving as the director of the Racial Justice Project for the ACLU of Northern California, where she helped lead a national campaign against racial profiling. Currently she devotes her time to freelance writing, public speaking, consulting, and caring for her three young children.

Alexander is a graduate of Stanford Law School and Vanderbilt University. She has clerked for Justice Harry A. Blackmun on the U.S. Supreme Court and for Chief Judge Abner Mikva on the D.C. Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals, and has appeared as a commentator on CNN and MSNBC, among other media outlets. The New Jim Crow is her first book.

For more information, visit www.thenewjimcrow.com

Image: Ron Haviv / VII Photo

UPDATED: 06/27. 4:25am EST

Following the September launch of VII Photo/Think Outside the Cell’s collaboration, Prison Photography will roll out four related interviews with each VII photographer to capture first hand the journalists’ perspective on reentry, on the images and video they made, on the stakes at hand for subjects who are navigating a precarious time following their incarceration and on the relevance of image to public attitude.

– – – – – – – –

On Saturday afternoon, I listened to Michael Shaw’s lecture about how governments and corporations are increasingly influencing flows of images through strategic releases and staged ops. In a time of shrinking budgets, especially among printed media, we are all aware of how the modified – or sometimes not so modified – press release is quickly reworded and passed off as news. It goes without saying that this is a sad state of affairs. It goes with saying because below I am presenting an unmodified press release from VII Photo.

I should also add that I have spoken with a few representatives of VII Photo over the past few days and my decision to post this was also shaped by my keen personal interest in their professional pursuits as well as the personalities working away in VII’s Dumbo headquarters.

When I started blogging, I was a Billy-Nobody … and I rarely knew the photographers or organisations I was writing about. As time has passed, however, I am more frequently in the position of writing about the activities of people I know or with whom I may have shared a drink or meal.

Such a growing fraternity may not be unusual for anyone wending her or his way through any field – and this might be a disclaimer of unusual length – but I wanted to say that things feel different now.

I am not invisible anymore.

PRESS RELEASE

VII PHOTO AGENCY ANNOUNCES VISUAL COMMUNICATIONS PARTNERSHIP WITH THINK OUTSIDE THE CELL FOUNDATION

VII Photo Agency today announced a new long-term partnership with the Think Outside the Cell Foundation to produce documentary film and photography features that raise awareness about the experience of formerly incarcerated persons.

Think Outside the Cell is a non-profit organization founded in 2010 that works with the incarcerated, formerly incarcerated and their families to help end the stigma of incarceration. Through personal development workshops, storytelling and other creative approaches that provide building blocks for productive lives, the Foundation helps those affected by the prison system to create their own opportunities.

The first documentary feature project of this partnership will include a short film and photography essays that capture two subjects in New York City as they experience the daily challenges of reintegrating into society after being released from prison. The project will be launched Tuesday, September 18 on the Think Outside the Cell website and screened nationally at conferences, education forums, debates and in policy circles addressing legislation related to mass incarceration. The imagery and film will be syndicated by VII Photo internationally.

Each year, an estimated 700,000 people are released from prison in the United States, including approximately 26,000 in the state of New York. Often, people are branded as felons for life, and the stigma creates societal barriers that make successful reentry unattainable and staying out of prison with limited access to resources unsustainable.

VII photographers Jessica Dimmock, Ashley Gilbertson, Ron Haviv and Ed Kashi are collaborating as a team shadowing the subjects day-to-day as they deal with the challenges of reintegrating into society.

The partnership launches a long-term collaboration between VII Photo and Think Outside the Cell. VII will act as the Foundation’s exclusive visual communications partner with the aim of raising awareness about incarceration’s stigma and the local, state and federal laws that prevent formerly incarcerated persons from accessing the resources necessary to establish a stable and productive life.

“Think Outside the Cell is delighted to work with VII Photo in tackling head-on the stigma of incarceration,” said Sheila Rule, the Foundation’s co-founder. “Countless men and women who’ve been to prison have extraordinary potential, yet this crippling stigma has led to laws and policies that make it legal to deny them the essential components of full citizenship; employment, housing, educational opportunities, public benefits and the right to vote. Our visual partnership with VII Photo will open hearts and minds to the true impact of the long shadow of incarceration.”

Contact:

Kimberly J. Soenen

, Director of Business Development

Tel: 718.858.3130

kimberly@viiphoto.com

“Jackson and Christian have pulled back the proverbial curtain so that all can see the American Way of Death.”

– Mumia Abu-Jamal

In the 1979, Bruce Jackson and Diane Christian, a husband-and-wife documentary and research team conducted one of the largest (photographic) surveys of prison life. Jackson and Christian used photography, film and interview to understand and illustrate life on cell block J in Ellis Unit – the Death Row of the Texas Department of Corrections.

Their new book In This Timeless Time (University of North Carolina Press) offers an unflinching commentary on the judicial system and the fates of the men they met on the Row. You can see a gallery of 20 photographs from In This Timeless Time here, and an edit of 74 on Jackson’s own website here.

In This Timeless Time includes a copy of Death Row (1979) a film made by Jackson and Christian (trailer below). In This Timeless Time is also available as an e-book.

To coincide with the release Jackson and Christian have done a couple of interviews.

The first Listen, Read: Bruce Jackson and Diane Christian on Their New Book, “In This Timeless Time,” and Jackson on Curating “Full Color Depression” is with the Center for Documentary Studies (also abridged and in the online version of Document, Spring 2012 CDS Quarterly Newsletter.)

A second, very comprehensive interview Bruce Jackson and Diane Christian discuss Death Row in America is on the website of publisher University of North Carolina Press.

THE BOOK

In This Timeless Time includes 113 duotone photos, all accompanied by explanatory text, sometimes of considerable length. The book is divided into three significant sections.

First is a survey of their work:

“Instead of just showing those men as they were then and printing in another section their words about their condition then, this book tells what happened to each of them: who was executed, who got commuted, who was paroled and who, after more than two decades on the Row, was found to be innocent,” say Jackson and Christian.

Second is a look at capital punishment across the United States since Gregg v. Georgia (1976) in which the Supreme Court ruled states could resume executions.

Third, Jackson and Christian talk about their own role as practitioners, academics and documentary makers.

“Usually with books like this, you just get a book about the subject with nothing about the intelligence that produced it, or the politics that produced it, or the work that produced it. We thought that should be part of it, too,” says Jackson.

I think this is incredibly significant inclusion. I approach photo-criticism with the assumption power is implicated in its manufacture; I want to turn the lens 180 degrees – so to speak – and investigate how those images came into existence. Jackson and Christian want to talk about relationships, want to talk about their privileged access and reinforce the issue of subjectivity. They made a body of work no one else could and others would make a body of work they could not.

This third introspective, “meta-documentary” section of the book distinguishes it from other books of prison photographs. I’ve yet to get my hands on a copy, but expect a book review in late 2012.

BIOGRAPHIES

Bruce Jackson, a writer and documentary filmmaker and photographer, is James Agee Professor of American Culture and SUNY Distinguished Professor of English at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Diane Christian, a poet, scholar of religious literature, and documentarian, is SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of English at the State University of New York at Buffalo

Churches, chapels, gardens, machine-shops, embroidery class, theatre, music shows, news room: not the usual spaces or activities one thinks of when considering prisons.

Adi Tudose went out of his way – and went to four Romanian prisons (Craiova Prison; Bucharest-Rahova Prison; Bucharest-Jilava Prison; Giurgiu Prison) – to document the men engaged in what we can presume are edifying activities.

The title is Prisons of Romania, not “some prisons” or “worthwhile prisons”, but the prisons of the nation. To me, the title “Prisons of Romania” infers that Tudose wants these images of self-improvement and – dare I say it – redemption, to be the dominant visual of incarceration in Romania. Tudose may want to show that all is not lost and that there is even space in prisons for initiative. This might be over-reading the images on my part, or if I am close to guessing the Tudose’s motivations, it could as easily be propaganda on his part?

I mainly wanted to share these images because after interviewing Ioana Cârlig, I realised I knew nothing about Romania or the photo communities therein. I’ve since submitted follow-up questions to Ioana about the life of a young photographer in Eastern Europe. In the meantime, we can meditate on Tudose’s images.

Tudose visited the four prisons between August and October of 2011.

Ioana Cârlig in Târgşor Prison

When I learnt of Ioana Cârlig‘s work in Romania, the name Târgşor Prison rang a bell. Indeed, Târgşor (alternative spelling, Tirgsor) was the site of photographer Cosmin Bumbuţ’s six camera workshop I wrote about two years ago.

I thought the chances of two photography events happening in the same Romanian prison were pretty slim, until I discovered that Târgşor is one of the few – if not the only – women’s prison in Romania.

From these two examples, I was assuming the Romanian prison authorities were progressive when it came to arts, access and rehabilitation. This may or not be the case. For a more informed view, I was excited to speak with Ioana Cârlig (25) who kindly agreed to talk about her approach and very recent experience photographing in Târgşor Prison.

Q&A

Can you describe your project?

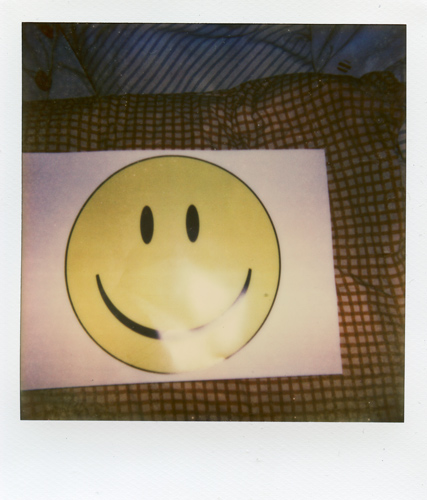

The project at Târgşor women’s prison is a collection of portraits and Polaroids. I wanted to find out what they think about the stuff they can’t do while they’re inside – what they miss, especially ask about the little things like taking a walk in the park, or having a beer on a terrace, or dressing up to go out on a date. Basically, I took a Polaroid of one of the things they said they miss. I show the Polaroids next to the portrait.

The goal was to show a person, a woman and not a spectacular bad-girl who is fascinating to the public because she looks dangerous.

Can you describe Târgşor Prison, in which you’ve been making these photographs?

The first thing I thought about Târgşor is that it’s so much cleaner and nicer and better smelling than a men’s prison. They have pink bed linen, stuffed animals neatly organized on the beds, all kinds of objects that are of no use other than being nice and making their rooms feel more home-like. I became very attached to the place and to some of the girls, even though I didn’t have as much time as I had hoped.

You ask the women what they miss. Why?

I think what people miss when they don’t have access to their normal routine is what is in fact essential to their spirit, their life. All the women said they miss their family and friends. That’s the first, probably most painful layer.

Then, they think about something smaller that was probably part of their everyday life, like sitting all Sunday in bed or going out for dinner or going dancing. I don’t know if the answers are memorable, they’re just normal stuff. A lot of the women said they missed taking care of their homes or going to the seaside with their family or cooking a certain dish. The younger ones said the missed going out dancing or on dates or hanging out with their friends.

What do the women think of your project?

Some thought it was interesting, some didn’t really understand what I was going on about, some thought it was fun to talk to me and get their picture taken, it helped pass the time I think. All of them were really happy that they were getting pictures to send home. Every Wednesday, I went there with an envelope full of printed pictures.

What do the staff think of your project?

The staff was nice enough. I initially had approved access for four months, but ended up with two, which meant 2-3 hours every Wednesday. I went there 9 times and got “guarded” by different people, they were nice and helpful, but probably my activity was disruptive to their usual routine so the people in charge decided to cut it short. Maybe I’ll try again after some time passes and they forget about me.

What does the prison administration think of your photography?

I’m not sure what they think. I know they don’t understand why I’m doing it and they probably think it’s kind of silly. They’re also probably happy it stopped.

What negotiations did you go through with the administration to get approval for the project?

First, I got a signed approval from A.N.P, which is the Nation Prison’s Association. Then I went to Târgşor and spoke to one of the people in charge, who spoke to one of the people even more in charge and so on. I was granted a few hours every Wednesday. It wasn’t what I had hoped for but I knew from the beginning there were slim chances of getting a lot of time.

Why the two different processes (square portraits and Polaroids)?

I used Polaroids to take a picture of one of the things every woman said she missed, just as a symbol. I thought the picture would have a more personal effect. I use squares for the portraits because I love shooting portraits on medium format film.

Do you have a particular view on prisons and/or their worth?

I think society relies to much on just imprisonment to make everything bad go away. In Romania, we have serious problems with education and social services. We have serious problems with lots of things, as I’m sure most societies do, but I think just creating a functional prison system in not enough. And a lot of people seem to be convinced it is, even though they may not admit to it. A lot of the people incarcerated come from poor families and bad entourages and after a few years most of them will be back on the streets doing the same things.

In Romania, what is the general public’s attitudes towards prisons, crime and punishment?

The general public attitude is that bad people should be locked up and taken off our streets and prisons are the quick solution.

A few people have asked me why take pictures of prisoners and not poor children or some other socially disadvantaged group; why photograph these women who kill, steal and deal drugs? I suppose it’s easier to have everyone categorised, but I try not to.

And, in Romania, what is the general public’s attitudes towards female prisoners in Romania?

I think women prisoners are seen as something a bit more exotic because a pretty woman with long hair wearing a flowery dress doesn’t go well with the stereotype we have for the criminal.

What are you thinking about when you are making photographs? How are you conducting yourself with your subjects?

I tried to talk to them as much as I could in the little time I had. Once I start photographing, I try to say things to make the person as comfortable as possible. With some people it’s very easy. While I’m taking to pictures I’m just focusing on the changes in the person’s face and body posture and try to get connected to the atmosphere and the moment. To me photographing is a magical experience, as cheesy as that might sound.

Is this work complete? Is it long-term? What are your goals with it?

Last week, before I left Târgşor, I was informed that I cannot continue, so for now I’m done photographing there. I hope to go back and maybe expand the project to other prisons in the future. After I finish scanning all the film I will make a selection and upload it on my blog and on the website that I hope to have ready soon. I also hope to have an exhibition in the near future.

Are people surprised that you’re going into prisons and working with a population that many consider dangerous?

My family and non-photographer friends are a little worried I think, but by now they have probably got used to my unconventional passion.

Your friend and supporter Constantin Nimigean introduced me to your work and suggested it needed a helping hand. What sort of support do you need?

I organized some crowdfunding to help me go through with this project. Money is always an issue; documentary photography isn’t exactly a gold mine! Between my job and my freelance work that help me save up for my personal projects, there’s not much time left to apply for grant and funding opportunities and work on the self-promotion part.

Right now I have to focus on getting the money to fund an exhibition with these pictures.

All Images: Ioana Cirlig

As many of you will be aware, Noorderlicht Photo Gallery and Photo Festival are threatened with closure if the Dutch government decides to go ahead with advice – by the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture – to cut €500,000 in funding. That amount represents 50% of Noorderlicht’s annual budget.

As many of you will also be aware, I have been a public champion of Noorderlicht. Last month I described my delight with working with the professionals at Noorderlicht; the post covers all the reasons I believe Noorderlicht is unique, principled and vitally important to the documentary tradition, as well as to all discourses within photography.

I won’t repeat myself here then in this post. Instead, I’d like to look at some of the language used by both the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture (or the The Cultural Council of The Netherlands, as it is alternatively known) and Noorderlicht.

CONTEXT

Noorderlicht has operated since 1980. It’s history and growth is impressive. There can be no mistake, Noorderlicht is of international importance. This is a fact, I think, the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture has paid least attention to. The Dutch are known for their exception book design, but in Noorderlicht they have an international pioneer in the genre of socially engaged documentary.

Unfortunately, that is part of the problem. The Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture characterises Noorderlicht as having to heavy a focus on documentary work and not enough participation in “the art discourse, theoretical reflection and experimental development.”

Noorderlicht has publicly responded to the recommendations twice (one, two).

Up front and to the point, Noorderlicht quotes the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture, listing the most direct of criticisms:

‘The figures for fund raising and sponsoring give evidence of limited insight.’ ‘Disappointing income of their own.’ ‘Because of the complex character it draws only a small audience.’ ‘Conveyance of information by discourse appears to weigh more heavily than visual qualities.’ ‘The number of visitors was very low.’ ‘Concrete plans in the area of education and an outreach to a wider public are lacking.’ ‘There is a concern that the peripheral programming with debates and publications is being privileged at the expense of appealing presentations.’

Noorderlicht does this in order to respond square on:

“Noorderlicht reaches a wider public than institutions that did receive a positive recommendation, has remained critical and self-critical, has generated great enthusiasm and earned an international reputation that the whole of The Netherlands can be proud of. That must not be allowed to be lost.”

Noorderlicht’s overall rebuttal goes into details of how it has “met all criteria.”

Ton Broekhuis, Noorderlicht director, wrote in an open letter to Joop Daalmeijer, president of the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture:

“I dare to say that the Cultural Council’s final verdict on Noorderlicht was made on the wrong grounds; by this I mean purely theoretical, and certainly in terms of the interpretation of our quantitative data. You advise some whose requests were accepted to generate larger audiences and work on their business model. Noorderlicht has already accomplished these things. And yes, that was at the expense of the elitist, hothouse art debate.”

The politics of funding must also be examined. Noorderlicht argue regional inequalities and bias are at play:

Of the thirteen Northern institutions that several years ago were still financed wholly or in part by national disbursements, only four remain. Certainly in Groningen, where for instance all dance and all visual art is being scrapped, the clear fell is complete. A region where 17% of the country’s population lives is being palmed off with a disproportionately small share in national subsidies. The Council has clearly chosen for the Randstad (the conglomerate of big cities in the west of the Netherlands) and for a number of big players. In itself, this is not surprising: when only 10% of all the advisors come from outside the Randstad, a certain Randstad myopia is built into the process.

Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture also criticised Noorderlicht for not collaborating enough across the Netherlands. Noorderlicht’s response:

Why should Noorderlicht, as an autonomous institution which has set itself the task of operating internationally from the North of The Netherlands, have to show how it works with other institutions in the country? Are institutions in the Randstad also asked how they work together with national institutions in the region? How often do Randstad institutions present their products in Groningen?

Noorderlicht concludes with its view on the recommendation to cease funding:

“[…] The council is making a clear first move in a debate that has become urgently necessary. For whom is art? What is the role of art in society? In any case, Noorderlicht has a less narrow view on this than the Council does.”

This is all very punchy stuff and part of what is now undeniably a noteworthy, frank and public debate.

HAVE YOUR SAY

Noorderlicht has asked supporters to record video messages of support Send the file to Noorderlicht and they’ll post it on the Noorderlicht Youtube page. You have a spare minute?

Ed Kashi, on Noorderlicht Photo Gallery and Photo Festival: “National Jewel […] It is unthinkable to think that Noorderlicht would disappear.”

Other ways to support.

SEE ALSO

– Joerg Colberg’s Open letter in support of Noorderlicht: “Noorderlicht [has been] an important member of the photographic community for many years, a community that extends beyond regional or national borders.”

– Noorderlicht Photofestival faces closure, British Journal of Photography, 22 May 2012.