You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

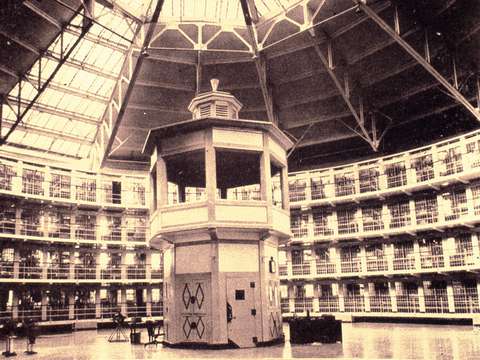

Carandiru, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil – 2003 © Pedro Lobo

Four South American penitentiaries feature in Pedro Lobo‘s series Espacos Aprisionados/ Imprisoned Spaces; Itaguy, Bon Pastor and Bela Vista prisons in Medellin, Columbia and the infamous Brazilian prison Carandiru in Sao Paulo.

Pedro Lobo has posted an edit of prison images on his website (27 images). A larger selection can be found at Lobo’s Photoshelter gallery (86 images). Selected works are also posted to Lightstalkers (13 of 30).

I think his images from Carandiru – which he shot shortly after its 2002 closure and demolition – are the most cohesive as a group, and it is a selection of those I include here.

Carandiru, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil – 2003 © Pedro Lobo

Lobo adopts a common approach to prison interiors as he does to the vernacular architecture of slums and to adapted religious spaces. Lobo is interested in the strain between the inhabitants control over the space, and the control of the space over its inhabitant. Read in the details, it is – strangely – a very compelling tension.

Lobo: Brazilian inmates call their cells “barracos” (barracks, tents, shacks) the same word used for their houses in the “favelas”, where most of them come from. As in my previous work, I tried to show their efforts to make their living quarters as dignified as their meager resources allowed for.

In this prison, inmates were allowed intimate visits twice a month and made all efforts to clean and decorate their cells prior to these encounters. The art work on walls and doors are reflections of order and chaos – creativity in adversity – and revealing of their desire for freedom, material residues of the only allowed forms of self-expression. It is sad to know that all vanished when the buildings were demolished.

These images reflect the responsibility with which I use my work. They are not about crime, or criminals, poverty, or misery, but about human beings who found, or placed, themselves in extremely adverse situations and decided not to give up the struggle for a dignified existence. (Source)

Carandiru, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil – 2003 © Pedro Lobo

In some cases the interiors are bare and contemplative; images 2 and 3 could be the cells of religious devotees. In other cases (image 1) the intrigue is in the particulars. Look closer. What’s behind the curtain?

Especially because Carandiru no longer stands (it has, like so many former prisons, become a museum) Lobo’s pictures should be treasured. Don’t be surprised if these images reemerge, possibly in the form of a book, and probably tied into his wider body of work.

PEDRO LOBO

Pedro Lobo (Rio de Janeiro, 1954) is a Brazilian photographer currently living in Portugal.

He has exhibited his work in Brazil, Denmark, Germany, Colombia and in the United States. He has photographed slums, favelas and prisons. His images of known as Carandiru (later demolished) in Sao Paulo were shown in the exhibition “Imprisoned spaces/Espaços aprisionados” at Blue Sky Gallery, in Portland, Oregon, in 2005.

His first one-man show in Portugal was “Favelas: Architecture of Survival“ at Museu Municipal Prof. Joaquim Vermelho in Estremoz.

He has taken part in other exhibitions such as REtalhar2007 in Centro Cultural do Banco do Brasil in Rio de Janeiro and “Via BR 040 – Serra Cerrado”, with Miguel Rio Branco, Elder Rocha, etc in Plataforma Contemporânea of the Museu Imperial of Petropolis, in 2004 and 2005.

Pedro Lobo, a Fulbright Scholar, studied photography at the school of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts with Elaine O’Neil and Bill Burke and at New York’s International Center of Photography (ICP). From 1978 to 1985 he worked for the Brazilian Landmark Commission (Fundação Pró-Memória) as a photographer and researcher. In 2008, he was awarded the first prize at Tops Festival in China.

I just came across Francesco Rocco‘s Prisons portfolio and it was a punch to the gut.

Cocco portrays the self-afflicted and architectural violence wrought in Italian penitentiaries with visceral power that – even within the genre of prison photography – is rare.

The work was made against the ongoing outcry of suicides in Italian prisons, “Italian prisons are increasingly overcrowded. In eight years, 449 suicides have been counted in Italian jails, out of a total of 1243 deaths behind bars. Is this a way to resolve a social issue? Unfortunately, a neon light isn’t enough to take away a man from darkness and hand back to him his dignity.”

In 2002, Cocco embarked on a long study of men’s and women’s prison conditions in Italy, creating work shown at the Modena, 55th Festa Provinciale de l’Unità, September 2006; and later at Rome, Sala Santa Rita, March 2007.

A video of the exhibition installation with comments from the Modena curators (Italian language) can be watched here or by clicking the image below.

Prisons was published as a book format by Logos, with texts by Adriano Sofri and Renata Ferri.

A well-designed fold out accompaniment to the exhibition (pictured below) was also produced. More here.

ITALIAN PRISONS

Previously on Prison Photography, as regards Italian prisons, I have featured Melania Comoretto‘s portraits of women, Danilo Murru‘s large format architectural studies of Sicilian prisons and Luca Ferrari‘s B&W portraits from Rebbibia prison, Rome.

FRANCESCO COCCO

Francesco Cocco was born in Recanati, Italy in 1960. He began working as a photographer in 1989. Keenly interested in social marginalization and the world of children, he immediately started visiting ‘difficult’ countries, especially in Asia. In Bangladesh, he photographed the living conditions of street kids and documented child labor practices. In Vietnam, just after the borders reopened, he created a photo essay for the exhibition Vietnam Oggi (Modena, Italy, 1993). In Cambodia, working with Emergency, he tackled the dramatic story of landmine victims. In the same country, with the support of the NGO New Humanity, he collected images of child prostitution. In Brazil, he photographed blind people at the Benjamin Constant Institute in Rio de Janeiro and the exploitation of child labor on the island of Marajoa, in the Amazon basin.

Sometimes the simplest ideas are the best. With the aid of inmate Renata Abramson (pictured in sceengrab below), Detective Kim Bogucki and Photographer/Film Director Kathlyn Horan co-founded The IF Project and asked ladies at the Washington Corrections Center for Women a single simple question:

“If there was something someone could have said or done that would have changed the path that led you here, what would it have been?”

Simply, the filmed testimonies (also here) and over 300 essays give the public an open line on the difficult lives these ladies have lived.

The lazy definition of ‘choice’ that everybody falls back on to justify punishments meted out upon the disadvantaged in our society – “they chose to do their crime, they do the time” – is exposed by these ladies’ stories. Many of them had no choice, at least not choice that would be obvious to an unloved teenager without any support, example or love.

I also know that The IF Project has expanded into men’s prisons in Washington State. Wonderful news.

IF you wouldn’t have noticed, the lady in the top image is cutting out the Washington Department of Corrections uniform badge.

IF you do anything today, spare 13 minutes for The IF Project trailer.

This recent release piques my interest:

Killed: Rejected Images of the Farm Security Administration prints 130 tri-toned black-and-white images scanned from negatives in the collection of the Library of Congress. Wiliam E. Jones’s book is the first to deal exclusively with the 35mm negatives that FSA director Roy Stryker killed with a hole punch during the early years of the project (1935-39). The book brings to light destroyed or defaced photographs by Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, John Vachon, and others; it also includes two essays by Jones discussing the images and possible reasons for their suppression.

You can search through the 175,000 Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives and pick out the punched prints yourself. Here’s some off just the first page.

In July, Foto8 reviewed the Punctured, a 5 minute film by the book’s author William E. Jones:

It was not so long ago that photographers and editors editing film would use a hole punch to indicate a selected frame, clipping a small half circle out of the edge of the frame by the sprocket holes where the frame number and film info had been burned into the emulsion during manufacturing. Stryker was more ruthless with his hole punch, “killing” the work of his photographers by punching a hole directly through the negative image. Unsurprisingly, the photographers objected to this practice, which Stryker ended in 1939. Many of the punched negatives survive in the US Library of Congress FSA archives.

Punctured, Jones explained, is about the “Interface between image making and power… what images authority gives us and what we do with them.” Jones’ effort is to unsettle those relationships and to this end Punctured is articulate in its explorations of the way that archives are constructed, of the FSA archive specifically as the product of Stryker’s judgments …

OTHER PUNCHY CONTRIBUTIONS

This all leaves me thinking of Lisa Oppenheim‘s Killed Negatives: After Walker Evans.

Lisa Oppenheim, from the project Killed Negatives: After Walker Evans

Carefully Aimed Darts points out the Etienne Chambaud also made use of the defaced FSA negs for the show A Brief History of the Twentieth Century

Installation shot, Etienne Chambaud: Personne, 2008

If only for the similarity between precision-cut and precision-painted holes I am left thinking of John Baldessari:

John Baldessari. Hitch-hiker (Splattered Blue) 1995. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © John Baldessari. Colour photograph, acrylic, maquette

Ernest Morgan, an inmate since 1987, holds his prison-approved CD player. Photo: Jon Snyder/Wired.com

My friend and colleague Matt Shechmeister at Wired’s Raw File just published Life on Lockdown: See-Through Gadgets, DIY Media, No Internet, an article and gallery on idiosyncratic prison technologies.

Matt went to San Quentin Prison with photographer Jon Snyder (@jonsnyder) to tour cells and music studios to report on the see-through typewriters, prison-sanctioned music selections and contracted companies all shaping the security-minded tech-culture at San Quentin.

Not an angle seen or read very often. Well worth checking out.

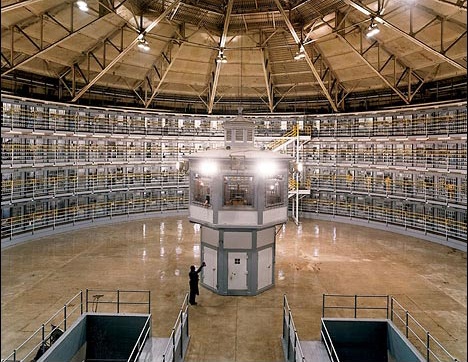

Leventi, David - Stateville, Joliet, IL

Following my recent post of David Leventi‘s work, a reader contacted me to alert me of the potential (and presumably happenstance) development of Stateville Correctional Center, Joliet, Illinois as an art object.

Consistently through the representations of Stateville is the description of the roundhouse as one of the last remaining prisons in America adhering to the Panopticon model developed by Jeremy Bentham.

Let us be clear, the Panopticon is an outdated and abusive model for corrections; it relies on a small number controlling a large number through the threat of constant supervision. Modern correctional management must look beyond disciplinary techniques based upon spatial arrangement and look toward truly transformative (educational) engagement with prison populations.

Still one can only speculate that the roundhouse prison is of interest to artists primarily because of its “purity” of form as understood – and communicated – through the formal qualities of composition within the photographic print.

USA. Illinois. 2002. Stateville Prison. F house. There were originally four circular cell houses radiating around a central mess hall. The buildings were based on Jeremy Bentham's 1787 design for the panopticon prison house. The first round house was completed in 1919, the other three were finished in 1927. F house is the last remaining panopticon cell house. It's used for segregating inmates from the general prison population and for holding inmates who are awaiting trial or transfer. -Doug DuBois & Jim Goldberg.

In 2002, Doug Dubois, along with Jim Goldberg, went to Stateville Correctional Centre, and took a picture (above) of the prison’s interior. The New York Times later published the photograph.

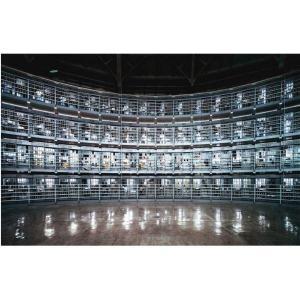

A while later, Dubois found out that Andreas Gursky had too gone to Stateville, apparently inspired by Doug and Jim’s photograph and took a picture himself (below). Gursky has admitted in his career he finds ideas for images in newspapers and other popular media. Gursky’s image put in context here, at the Brooklyn Rail.

Andreas Gursky, “Stateville, Illinois” (2002), C-print mounted on Plexiglas in artist’s frame. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

So, this raises questions. Has Stateville prison inadvertently become a tease, and a subject for curious photographic artists?

Do the individual activities of artists have a bearing on one another? Should these images exist within the same discourse? Do photographic attentions of the 21st century have any relation to the need and stresses of current correctional politics in Illinois?

Does the ascendancy of Stateville onto gallery walls effect any significant – or measurable – impression of Stateville prison within public consciousness?

Or are Dubois, Goldberg, Gursky and Leventi just continuing an intrigue which has continued throughout the decades?

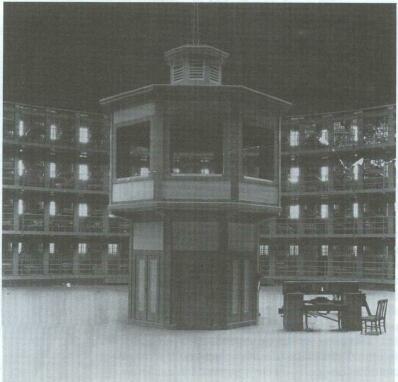

Postcard: Stateville Penitentiary, near Joliet, Illinois (ca. 1930s).

Postcard of an American panopticon: "Interior view of cell house, new Illinois State Penitentiary at Stateville, near Joliet, Ill." Source: Scanned from the postcard collection of Alex Wellerstein. (Copyright expired.)

Photo of guard tower in round house at Stateville. Courtesy of Illinois State Historical Library. The second state prison was authorized at Joliet in 1857. It was built by convict laborers. That 135-year-old Joliet prison still houses more than 1,100 inmates. Meanwhile, Stateville. prison, also in the Joliet area, opened for business in 1917.

Inmates at Stateville Penitentiary in 1957. (Sun-Times News Group file photo)

Prison guard in a security tower, Stateville Penitentiary, Joliet, Illinois, USA. © Underwood Photo Archives / SuperStock

Panoptic guard tower at Stateville Prison, Stateville Prison (US Bureau of Prisons, 1949, p. 70), 1940s

At this years Les Rencontres d’Arles Photographie Festival the official photographs of the French prison inspectorate make up an exhibition entitled Behind the Walls of Cliche.

The independent French prison inspectorate (contrôleur général des lieux de privation de liberté) is nominated for six years and during that time he cannot receive any instruction from any authority; he can be neither removed nor renewed; and he cannot be prosecuted for his opinions he formulates or for the actions he carries out in his functions.

Currently, the director is Jean-Marie Delarue (here’s an interview with him about the state of French prisons).

Delarue’s team take photographs as documentation as they tour France’s prison system and it is these images that are currently on show at Rencontres d’Arles.

To my mind, this is a truly unique exhibit. I know not of any other arts festival that has put front-and-centre the administrative photography of a working independent or government agency overseeing prisons.

BLURB FROM LES RENCONTRES D’ARLES SITE

Sixty thousand detainees in French prisons: surely the problem can’t be all that hard to solve!

The Rencontres, in their own way, are part of the media, and this exhibition based on the report of France’s Inspector General of Prisons, Jean Marie Delarue, shows just how the world of French gaols, far from being an aid to social reintegration is, rather, an insult to the human condition. This is a call to look beyond the standard ideas about prison.

The exhibition also demonstrates the limitations of photography, which cannot convey the nuances of everyday unhappiness in prison. In a photo a TV set, a workshop and a library seem to offer possibilities which in fact are non-existent for most prisoners, and certainly not available on a regular basis. The rules of hygiene and safety are flouted every day, the psychological stresses are chronic, and the laws regarding the minimum wage and access are broken by the state itself. None of this is visible in a photo.

Pictures of a new prison seem to suggest a solution; but the image doesn’t tell you that new prisons have a higher suicide rate than old, dilapidated ones. Three people in a cell is something you can see; but what you don’t see is that one inmate standing means two lying down, because there’s nowhere to sit. And with prisoners spending 22–24 hours a day in their cells, it’s easy to imagine their physical and psychological state.

This is definitely not photojournalism, but rather an alarm signal regarding one of democracy’s least well known instruments.

François Hébel, exhibition curator

Excerpt from Law no. 2007-1545 of 30 October 2007:

’The Inspector General of Prisons is an independent authority whose duty it is, without prejudice to the prerogatives attributed by the law to the judiciary or jurisdictional authorities, to monitor the conditions of incarceration and transfer of persons legally deprived of their freedom, so as to ensure respect for their fundamental rights.

Within his field of responsibility, he takes no orders from any authority… He cannot be relieved of his duties before his term has expired… The authorities in charge of places of imprisonment cannot oppose a visit by the Inspector General except for grave, imperative reasons relating to national defence. The Inspector General may demand from those authorities all information and documentation required by the carrying-out of his mission. In the course of his visits he may speak, under circumstances guaranteeing the confidentiality of what is said, with any person whose participation he sees as necessary.

At the end of each visit the Inspector General makes known to the relevant ministers his observations regarding the state, organisation and functioning of the site visited, and the condition of those imprisoned there… Each year the Inspector General submits a report to the President of the Republic and to Parliament. This report is made public.’

The 2009 report is published by Dalloz.

PREVIOUSLY ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

I’ve noted French prison photography before. From Jean Gaumy, the first photojournalist in the French prison system to contemporary artist Mathieu Pernot; from the archives of Henri Manuel to portraitist Phillipe Bazin; and to the recent exhibition Impossible Photography – artistic survey of French prisons.

– – –

Of course, if you want to get really involved check out Melinda Hawtin’s French Prison Photography graduate work.

France even has its own National Museum of Prisons!

– – –

Thanks to Yann Thompson for the tip!