You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

© Thomas Hawk

Thomas Hawk’s images are being used by police to pursue Oakland looters:

“I recognized several of the photographs that the Oakland PD had released as my own photos that I’d taken the night of the riots and had posted to my own Flickr account. I was never contacted by the Oakland PD regarding their use or distribution by Oakland PD. It’s interesting to see law enforcement taking photos by citizen media and using them this way.”

Under Creative Commons (which these images were) there is no problem with anyone, including police, “to copy, distribute and transmit the work” provided they attach attribution. Unfortunately, the Oakland Police Department didn’t name Hawk as the photographer, seemingly passing the images off as their own.

Here’s the San Francisco Chronicle article in which Hawk found his photographs.

(via)

If you are in NYC and you’re quick on your feet you might just make it to Zwelethu Mthethwa’s artist’s talk tonight. Followed by a reception and book signing at Museum of Contemporary Diasporan Arts in Brooklyn (begins at 6.30pm).

Mthethewa’s work will be on view at The Studio Museum in Harlem until October.

AFRO-PESSIMISM

Afro-Pessimism is a term introduced by Okwui Enwezor (for the essay of Mthethwa’s monograph) in an attempt to describe what Zwelethu Mthethwa’s art is not.

I had dozens of working titles for this blog post each one reflecting an approach (and/or quote) by Mthethwa which described his process, his collaboration with the sitter, the waves of culture in which we exist, whether poverty in photography is a problem for the practitioner or audience, etc, etc. These topics are too huge for a title of course, fortunately there’s plenty of wonderful online videos and chances to hear Mthethwa talk about his art:

Aperture (who are publishing his first monograph) has a four-part interview, Zwelethu Mthethwa: In Conversation with Okwui Enwezor.

The Mail & Guardian has a narrated slideshow, “I hope when people look at these images they are honest and open to learning new things.”

Dazed and Confused visited Mthethwa in his studio, which is a fascinating look at his work space. A great painter as well as a great photographer!

ESSAY

For the SFMoMA ‘Is Photography Over Symposium’, Okwui Enwezor leans on Mthethwa’s work to ask, “How do diverse cultural practices engage with the legacy of photography?”:

“Before foreclosing the effectiveness of photography or to ask whether we have reached the end of photography, we should address the diverse manifestations of photography in societies in transition where its powerful effects of seeing is constantly battling different logics and apparatuses of opacity. All through the years of apartheid, photography was at the center of this battle between transparency and opacity, thus lending the medium a far more discursive possibility than it would have enjoyed as purely an instrument of art. One can in fact, argue, pace Georges Didi-Huberman, that in the context of apartheid photography was an instrument of cogito.”

“In South Africa, for the critics of documentary realism or anthropological realism, especially black artists such as Mthethwa, documentary realism was always at the ready to link the iconic and the impoverished with little recourse to examining its spectral effects on social lives. Because of this, documentary realism generated an iconographic landscape that trafficked in simplifications, in which moral truths were posited without the benefit of proven ethical engagement.”

From what I can gather Georges Didi-Huberman’s thesis is that images are killed, denied their truth, narrative or violence within the dominant art historical canon that has elevated the image to art. The image becomes cogito – an object of thought – not an object pertaining to reality or even to action.

Mthethwa’s images are against such failings; they are attempts at transparency, honesty. Mthethwa talks in the interviews about his ethical and slow engagement with his subjects.

Afro-Pessimism is on the decline.

BIOGRAPHY

Zwelethu Mthethwa (born in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 1960) received his BFA from the Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town, a then–whites-only university he entered under special ministerial consent. He received his master’s degree while on a Fulbright Scholarship to the Rochester Institute of Technology. Mthethwa has had over thirty-five international solo exhibitions and has been featured in numerous group shows, including the 2005 Venice Biennale and Snap Judgments at the International Center of Photography, New York. Mthethwa is represented by Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. He lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

Mari Bastashevski photographs the rooms of victims of kidnap. “Abduction as a concealment tactic became prevalent in 2000 during the second Russian-Chechen conflict. The practice continues today. The rooms are preserved by family members who don’t know the fate of their loved ones,” says Bastashevski.

It’s no surprise that since her Open Society Grant and subsequent exhibition in New York and Washington D.C., Bastashevski should have become the trendiest thing in art-documentary. (The New Yorker, Lens Blog, ThePhotographyPost)

I’m not being flippant here; I think her work is remarkable and I also think it is successful in translating the bleakness of the situation for abductees and the families left behind (not all photography can elevate an issue in this same way).

‘File 126: Disappearing in the Caucasus’ has all the right ingredients to hook the Western audience; the cachet of post-Cold-War politics; the same cold-exoticism of photographers such as Carl de Keyzer or Bieke Depoorter; the details of anaesthetised domestic interiors; and fundamentally, hundreds of profoundly tragic and must-be-heard stories about political terror.

Russian-born Bastashevski read the case files before she began visiting families. Human rights organizations in the Russian North Caucasus have spent years documenting the abductions of young people, which they attribute to the state security forces conducting a brutal counter-insurgency campaign[ …] Some stories verged on madness, like the genteel lady who was certain, after five years, that her sons were still alive in a secret prison in the forest, if only she could reach them. (Source)

DIFFERENT CONTINENT, SAME CRIME

One of the reasons I am so interested in Bastashevski’s work is that it mirrors the work – intellectually and in terms of its activism – of those photographers exploring and documenting the legacies and memories of the Disappeared in Argentina. (“Those photographers” I have written about before here, here, here and here).

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Image Caption: On June 10th, 2009 a group of military officials conducted a special, counter-terrorism, operation in Nazran, Ingushetia. In a course of the night, the men seized out of bed and dragged away a 23 year old Albakov Batyr. For two weeks Batyr remained missing. On June 13th., 2009, after two weeks of silence and uncertainty Batyrs mother saw her son on television. Literally torn to pieces, with arms barely connected to the torso, his body was dressed into insurgency clothing and was displayed covered in bullet holes. The TV network announced Batyr as one of the most wanted terrorist leaderer, killed during a spec. operation in the mountains. © Mari Bastashevski

2009 winner, Nadav Kander is on the jury for this years Prix Pictet.

That means two of the eight jurors I knew of. The other six are new to me:

The Prix Pictet Growth will judged by an internationally recognised panel of experts led by Professor Sir David King, Director of the Smith School of Enterprise and Environment at the University of Oxford. Other members of the judging panel include Shahidul Alam, Photographer, Curator and Founder of the Drik Agency in Bangladesh; Peter Aspden, Arts Writer for the Financial Times; Michael Fried, Art Historian and Critic; Loa Haagen Pictet, Pictet & Cie’s art consultant; Nadav Kander, Winner of the second Prix Pictet; Christine Loh, CEO of Civic Exchange, Hong Kong; and Fumio Nanjo, Director of the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo.

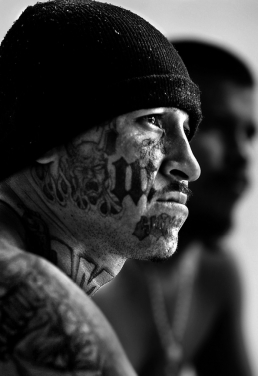

It seems like I’ve been saying a lot on prison tattoos (here and here) recently … which is true, but it’s not even an area of keen interest for me. Maybe this will be the last one, or maybe not, depending on what friends and photographers continue to produce.

I have expressed reservations about photographing prison tattoos because inevitably the images may fail to penetrate the coda that prisoners share, understand and guard.

Therefore, I applaud Bob Gumpert for providing his audience with as much understanding as he has drawn during his documentation. Accompanying American Prison Tattoos the multimedia piece published on Foto8 last week, Gumpert provides a “short and incomplete glossary of tattoo markings & terms” and a “list of slogans reflecting beliefs or attitudes.”

Of course, Bob Gumpert‘s work is about much more than just tattoos. He has been working in the San Francisco and San Bruno jails systems for 14 years and it touches upon every imaginable story of American cities, families and experience. I encourage you to check out Take A Picture, Tell A Story, his multimedia platform for his jail work; his general website; and his blog.

Last week, when Foto8 ran Katarzyna Mirczak‘s article about of the detached and preserved skin of prisoners’ tattoos, I was, of course, compelled to post about it. But, in truth, I need to do a lot more than duly note a story published elsewhere.

HOW HAVE PHOTOGRAPHERS TAKEN ON THE SUBJECT OF PRISON TATTOOING?

The simple answer is with limitations. Photography can describe tattoos very precisely, but description is not comprehension. Often, prison tattoos are a tactically guarded language.

Even if tattoo symbols are deciphered, they may carry different meanings in other cultures. Prison systems exist across the globe, within and “outside” different political regimes, thus the tattoos of each prison culture should be considered according to their own rules – and this caveat applies even at local levels.

Janine Jannsen offers a good introduction to the history of different tattooing cultures. She summarises tattooing in “total institutions” (navy, army, the penitentiary); tattoos and gender; and tattoos and the demarcation of space.

With regards to prison tattoos, maybe it helps us to think of photography as secondary to sociological research. Photography should be thought of as an illustrative tool to aid external inquiry.

That said, there are a number of photographers who have made honorable efforts to describe for a wider audience much of the significance of prison and gang tattoo cultures.

Araminta de Clermont

After their release from prison, Araminta de Clermont tracked down South African gang members and discovered their stories. Interview with Araminta and her subjects here.

© Araminta de Clermont

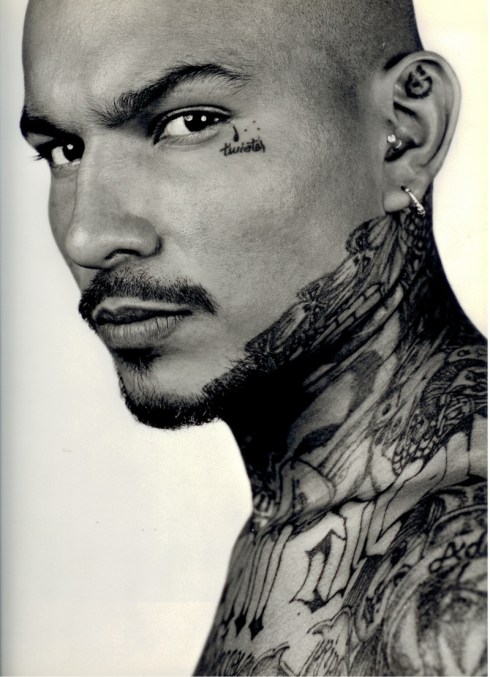

Donald Weber

Donald Weber mixed with former prisoners (‘zeks’) in Russia and concentrated on how their prison tattoos relate to their identity and criminal lifestyle. The relationships of these men with female criminals and prostituted women (‘Natashas’) who become their companions feature in Weber’s complex investigation.

“Some rules are simple: you can only get a tattoo while in prison.”

September 1, 2007: Vova, zek. The origins of Russia’s criminal caste lie deep in Russia’s history. Huge territories of Russia were inhabited by prisoners and prison guards. Thieves, or zeks, distinguish themselves from others by tattoos marking their rank in the criminal world: there are different tattoos for homosexuals, thieves, rapists and murderers. © Donald Weber / VII Network.

Rodrigo Abd

Rodrigo Abd‘s portraits of Mara gang members in Chimaltenango prison in Guatemala illustrate gang tattoos that are used less and less (from 2007 onwards) due to the unavoidable affiliation and violence they brought the bearer; “After anti-gang laws were approved in Honduras and El Salvador, and a string of killings in Guatemala that were committed by angry neighbors and security forces, gang members have stopped tattooing themselves and have resorted to more subtle, low profile ways of identifying themselves as members of those criminal organizations. Today, gang members with tattooed faces, are either dead, in prison or hiding.”

© Rodrigo Abd / AP

Luis Sinco

In 2005, Luis Sinco of the Los Angeles Times documented Ciudad Barrios Penitentiary in El Salvador, home to 900 gang members, many of whom have been deported from the US. Ciudad Barrios incarcerates only members of the MS-13 gang, which traces its roots to the immigrant neighborhoods west of downtown L.A.

“In the woodshop, inmates made a variety of home furnishings, most of which featured the MS-13 logo. The items sold outside the walls help supplement the prisoners’ meager food rations.”

“It was a of microcosm of L.A.’s worst nightmare transplanted. Claustrophobic, crowded tiers led to darkened, bed-less holding cells and fetid latrines overflowing with human waste.”

Multimedia here.

Moises Saman

In 2007, Moises Saman documented the anti-gang activities of Salvadorian Special Police and the inside of Chalatenango prison, El Salvador. At times Saman’s project focused on the tattoos but is more generally a traditional documentary project. More here and here.

© Moises Saman

Isabel Munoz

Much of Isabel Munoz‘s portraiture deals with markings of the body – what they reveal and conceal. For example, she has previously photographed Ethiopian women and their scarification markings. For her project Maras, Munoz shot sixty portraits in a Salvadorian prison of ex-gang-members. She also photographed the women in these mens’ lives. More here and here.

© Isabel Munoz

Christian Poveda

In El Salvador, Christian Poveda photographed and filmed Mara Salvatrucha (known as MS) and M18, the two Las Maras gangs in open conflict. Poveda wanted to describe their mutual violence and the absence of ideological or religious differences to explain their fight to the death. He described the origins of their war as “lost in the Hispanic barrios of Los Angeles” and as “an indirect effect of globalisation.”

Poveda was shot dead aged 52 as a direct consequence of his journalism. His work from El Salvador was entitled La Vida Loca. Full gallery can be seen here. B-Roll from his work can be seen here.

© Christian Poveda

More Resources

Ann T. Hathaway has collated (disturbing) information and links here about a number of prison tattoo codes.

Russian criminal tattoos have warranted their own encyclopaedia.

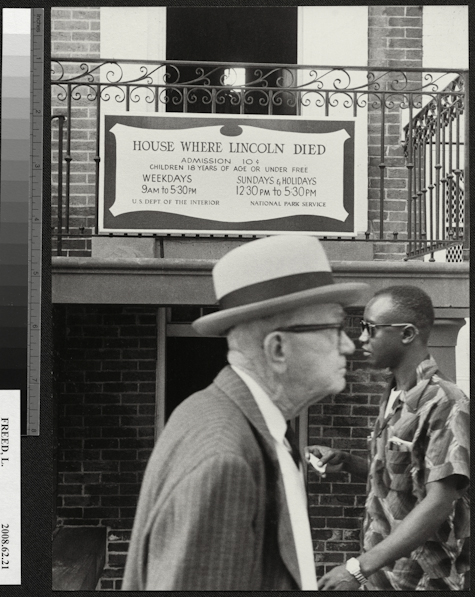

"New Orleans, Louisiana," 1965, by Leonard Freed. © Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos, Inc. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Kristina Feliciano interviewed Brett Abbott, curator of photography at the Getty, about their summer show Engaged Observers

Abbott succeeds in saying not a lot (it is a brief interview). Abbott lists the exhibit’s famous photographers and recounts the Getty mantra on commitment financial muscle to support acquire documentary photography.

That said, his analysis of Leonard Freed’s image (below) is pause for thought.

KF. What are some of your personal favorites of the photos on view in the show?

BA: Leonard Freed’s picture of two men passing one another on the street in Washington D.C.: Freed’s protagonists face off, their noses nearly touching on the two dimensional surface of the print. The older white gentleman occupies a commanding presence in the center of the photograph, but it is the African American on the right who is in focus. Within the context of Freed’s larger project on racial tension in America in the 1960s, they can be seen as representing basic and opposing forces of the civil rights movement: white and black, the old generation and the new, center stage and marginalized, present and future. Indeed, the two play out this dialectic beneath a balcony clearly marked as belonging to the house where Lincoln died.

"Washington, D.C., 1963" Leonard Freed (American, 1929 – 2006) © Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos, Inc. Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

BLACK AND WHITE IN AMERICA

Leonard Freed observed race in America throughout the sixties; this work eventually taking him to the prisons of Louisiana. Before we get to that, here’s how Magnum describes Freed’s best known work:

In 1962 Leonard Freed went to Berlin to shoot the wall being erected. There he saw an African American soldier standing in front of the wall and it struck him; that at home in the US, African Americans were struggling for civil rights, and here in Germany an African American soldier was ready to defend the USA. This prompted a lengthy examination by Freed of the plight of the African Americans at home in the United States. Freed traveled to New York, Washington, D.C. and all throughout the South, capturing images of a segregated and racially-entrenched society. The photos taken at that time were then published in 1968 in “Black in White America“.

The images below are from prisons within the same state, Louisiana.

Freed’s documents of the New Orlean’s City Prison are galling. The mood and theatre played out by these women (inmates? nurses? orderlies?) in the “white female quarters” as compared to the claustrophobia and groping along the “colored tier” is confusing, appalling.

I am at pains to know what scene Freed is capturing here in the “white female” section.

The screengrab (below) is taken from the first of two online videos – here and here – in which Freed talks about contact sheets; money and its’ substitute; motivations; and of course, race.

Freed discusses his experience on the “colored tier” from 4:36 to 6:00.

Screengrab. Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDVJlmE18zY

The attitude of the guards is beyond disgusting, “If we desegregate this place there will be blood. Mixing white men with animals. Can’t make us do that.”

If we take Freed at his word, and there is no reason not to, the portrait he paints of Angola was a place where Black men were willingly left to stew; a place where overcrowding was used as a disciplinary tactic, and a place in which racism was the unifying policy. Foul, totally foul.

YESTERYEAR / TODAY

That Freed should have visited a prison in the South as part of his survey on race in America was logical, for perhaps in prisons – more than anywhere else – the least tolerant and most simple interpretations on race existed.

Even today, prisons perpetuate cycles of poverty in minority groups. Furthermore, prison facilities only harden the tensions and misgivings between different racial groups of the prison population.

Freed went to Louisiana, but prisons across the South during the sixties were much of a muchness; they were borne from the same structures that had informed slavery. Robert Perkinson is perhaps the best historian to map this institutional-metamorphoses. In it’s basic premise, his recent book Texas Tough, can apply to prison management not only in Texas, but right across the South.

I highly recommend Marie Gottschalk’s review of Perkinson’s book which summarises his key positions, and is shocking enough in and of itself.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

ENGAGED OBSERVERS

PhotoInduced just reviewed Engaged Observers.

NPR ran a gallery pertaining specifically to the Engaged Observers exhibition.

FREED

Bruce Silverstein and Lee Gallery present Freed’s works online.

Screengrab - Inmate Benjamin Terry stands with Sierra, a mustang he trains as part of the Wild Horse and Inmate Program at the Cañon City Correctional Complex on March 17, 2010 in Cañon City, Colorado. © Dana Romanoff

This is a great photo essay, simply because it is a great story. Unexpected.

Dana Romanoff documents efforts by The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to round up wild horses and consequently tame them and offer them up for adoption.

“There exist approximately 63,000 wild horses under BLM management. The BLM currently has more than 36,000 horses in captivity in short term corrals and long term pastures. In 2009, the BLM removed 6,300 horses from the wild and in 2010; the BLM plans to remove nearly 13,000 more.”

“A few thousand of the rounded up horses temporarily live at the Cañon City Correctional Facility, Colorado. Under the Wild Horse Inmate Program (WHIP) inmates care for, train and ready selected horses for adoption by the public. Some say the Wild Horse Inmate Program “takes the wild out of both the man and the mustang.” Often an inmate has one horse that he works with and gets to name. Inmates learn a trade and the responsibility of having a job while horses are taught to trust humans, and be saddle and bridal trained. Both a bit spooked at first, the tattooed and muscled inmate and the scared and wild horse learn to trust each other form a bond.”

Who knew?

Well, probably many if they follow Getty Reportage, who are now also on Twitter at @GettyImagesRPTG.

See the prisoner-stereotype-busting images of ‘Wild No More’ here.

BLM

As a footnote, if you go ever go camping in the West do so on BLM land. It is well run, sparsely occupied and has fewer restrictions than any other government run land. For camping, conditions are perfect.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Who Knew? UPDATE (07.06.10)

Matt Slaby has also covered this story in the past.

BLM UPDATE (07.06.10)

While I’m yapping on about the quality of undisturbed camping, Ellen Rennard is bringing more serious questions to the table about BLM’s relationship with environment-killing big business. (See comments/sources below). Thanks Ellen!