You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

It has been said (although I don’t know enough about it) that meditation programs in prisons seriously reduce the violence of an institution. More than that, they can catalyse sea changes in the culture of an institution. Like I said, that opinion is anecdotal and I would assume the calming of any facility is due to many factors one of which may be the teachings of Buddha.

The movie has it’s own website – The Dhamma Brothers

– – –

I found this trailer on the blog of The Center for Documentary Studies. It was screened as part of Duke’s Ethics Film Series: “Control and Resistance.”

© Beb C. Reynol

Last month, I met social documentary photographer Beb Reynol.

For the past five years, Reynol has concentrated his documentary work in Central and south Asia, specifically in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Reynol has been an Artist in Residence at the Photographic Center Northwest and is now on its faculty.

In 2005, Reynol trained local photojournalists in Kabul with AINA, the non-governmental organization founded by veteran photojournalist Reza Deghati. AINA aims to rebuild the Afghan’s freedom of expression through journalism.

Whenever I look at imagery from the AfPak region I am consciously looking for work that does not depict military engagement. It was for that reason I was drawn to Reynol’s series of Afghan Coalminers.

Lit only by headlamps, the miners discuss the conditions of the shaft and their approach to the coal seam. Kar-kar, Afghanistan, May 10th, 2005. © Beb C. Reynol

© Beb C. Reynol

Beb’s The Cost of Coal in Afghanistan statement:

During past decades, Afghanistan has only known a succession of conflicts: the Soviet occupation, the Afghan civil war, the rise and fall of the Taliban and today American and allied military engagement. These wars ruined economic development and eroded the vitality of the Afghan population. Coal, abundant in Afghanistan, is an essential fuel used for the production of electricity, making it a basic need.

When Russian forces occupied the country in 1979, they sent their own engineers to run the large-scale production of natural resources. I visited a mine (difficult to access due to its geographical location) 12 kilometres northeast off Pol-e-Khomli. During the Soviet occupation, more than 2000 miners extracted the black gold from the mine. Today, the 150 employed miners barely cover the vast site and the hundreds of formerly excavated galleries.

Often working at a depth of more than 360 metres, the miners extract coal with only shovels and pick-axes in hand, battery powered lamps on top of their heads, and old equipment once imported from Czechoslovakia. Intense heat, total darkness and the risk of explosion from methane gas make coal-mining very difficult and dangerous.

The limited local demand for coal makes the mining far from profitable. Lacking reliable transportation and security infrastructure, the Afghan government is unable to exploit the fossil fuel. While the present war against the Taliban wages on, the country seems to be losing grip on its most wanted resource.

Coal mine, Kar-kar, Afghanistan, May 11th, 2005. © Beb C. Reynol

© Beb C. Reynol

I have also been thinking about Jim Johnson’s recognition of “powerful installment[s] in what should be considered a photographic tradition depicting men who work in extractive industries.”

If you are looking for a one-stop-shop for the visual politics of mining in photography then look no further than Jim’s posts labeled ‘Miner’.

Andrew Kaufman took a long look at religion in America during the Bush presidency. His multi-story project is irreverently titled The United States of God and the Jesus Freaks. One chapter is in the Broward Correctional Institute.

Religious missions are a mainstay of many American prisons. Christian programs constitute 65% of all volunteer efforts at the prison at which I work in Washington State.

Prison religious programs are not mandatory so I steer clear of accusations of manipulation. The carceral culture may be coercive but it’s dealing in hyperbole to equate prison fellowships with exploitation. For many, the cultural relevance of Christianity and evangelism makes prison worship an understandable choice.

Reasons for the existence – in some places prevalence – of evangelism within prisons are complex and many. I will defer to Kaufman’s observations to give context to these particular photographs and the matter of fanatic religion in prisons.

Q & A

Explain your title.

During the George W. Bush presidency religion was a constant topic. My photography of, and research into, evangelism started in 2003 when the Ten Commandments statue was removed from the Alabama State Supreme court. Since that time I photographed many different elements of the Evangelical movement including a drive-in church, Holy Land Amusement Park, a hip-hop church, Christian rock, the Global Pastor Wives Network, Billy Graham’s Last Crusade and then here, at a women’s prison bible group. At that point I had come to name the project ‘The United States of God’.

During the summer of 2004, I was watching Hawaiian TV and saw a young lady being interviewed. She had just been attacked by a shark and had her arm torn off. The interviewer asked her how she was coping and said she was doing great because she was a “Jesus Freak”. The interviewer asked her if she liked being called a “Jesus Freak”. She replied “Yes” as that was how she viewed herself. She identified with the idea. At that moment the working title of my project became ‘The United States of God and the Jesus Freaks’.

Why did you extend the project to a prison?

I researched evangelical Christianity in America and made contact with the Prison Fellowship for Women. I had always known that people in prison were interested in evangelism and atoning for the sins or wrongdoings. I don’t want to speculate but it seemed that the grief of being incarcerated is eased when finding prayer.

I made a few visits with the fellowship and eventually had an opportunity to see close up what they offer. I was compelled to photograph this segment of evangelism because I wanted to see different strata of society and how each prays.

What purpose does religion serve in this particular institution?

The prison allowed them to devote time and attention to their faith. It was fascinating to see how they cope with the incarceration and [see the] time that they need to heal and move on from emotional strain.

Did any of the prisoners receive prints?

As far as I know, none of the inmates have any physical copies of the images. The work is online so they might have seen the web. As I wasn’t family, it was difficult to communicate with the inmates.

“It was surprising for Norfolk to discover that the infrastructure of the internet age is as imposing, ugly and ‘real’ as the cotton mills, mines and factories of Victorian Manchester. Like pulling back the the curtain to find that the Wizard of Oz is actually a little old man, the cloud is no more than giant buildings full of computers, air conditioning units and diesel back up generators; there’s nothing fluffy or vaporous about it.” (Here)

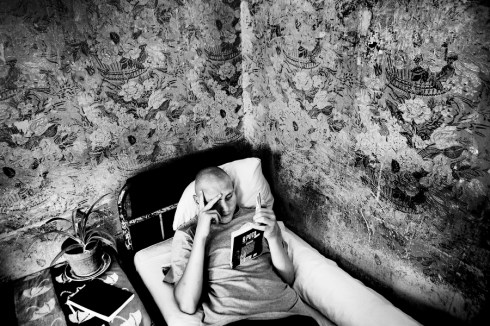

Every Wednesday the inmates have free time for a couple of hours in the afternoon, where they have to clean their dorm room, but there is also time to read a book. © Christian Als / GraziaNeri

Christian Als contacted me recently, to let me know of his project A Childhood Behind Bars.

Als visited Cesis Correctional Facility for Juveniles, Latvia’s only juvenile prison. A quick internet search indicated a paucity of information on Cesis; so this documentary project should be considered a important record of this particular institution and the lives contained within.

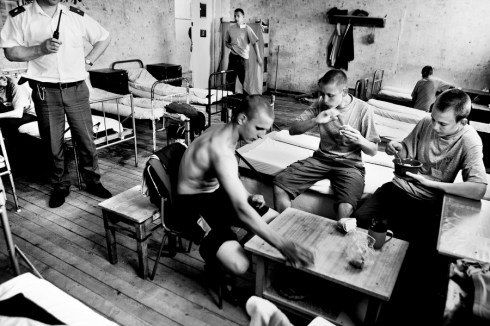

Cesis is situated one hundred kilometres northeast of Latvia’s capitol, Riga. It houses 140 young men between the ages of 14 and 21. As soon as the youngsters turn 21 they are transferred to adult facilities.

Als describes the young prison population as half Russian youth and half Latvian youth.

2007

The project is now three years old, so I encourage caution not to assume that all things are the same.

“A study from 2005 made by the ‘Latvian Centre for Human Rights’ evaluated the situation of juvenile prisoners in Cesis and gave recommendations how to bring the prison in line with International standards. So far nothing has been done and the prison looks like something out of Soviet Union and not EU 2007,” says Als

Latvia’s system for juvenile offenders is unique. “Four percent of Latvian prisoners are juveniles; that is a far higher rate of juvenile incarceration than other countries in the region. In comparison Sweden has only 0.2%, Denmark 0.6% and Poland 1.3%,” explains Als.

During the inmates free time some boys are eating soup and playing cards, while the warden is keeping an eye on the action. In Latvia the official standard for living space per juvenile prisoners is three square metres. In the section for sentenced prisoners, juveniles are accommodated in large dormitory type rooms for 20-22 inmates in eight units. © Christian Als / GraziaNeri

The boys are not allowed newspapers or television, because they are not to have any influence from the outside world. But the boys save pages from magazines and hang them on the wall. The most popular teenstars are Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera. © Christian Als / GraziaNeri

© Christian Als / GraziaNeri

WHEN IS A PRISON NOT A PRISON?

ALs recounts, “The management insists on calling the prison by other names like school, institution or home. The plaque outside reads: ‘Cesis Correctional Institution for Underage Children’.”

The age of criminal responsibility in Latvia is 14 years-old. Prior to the new Criminal Law of 1999, the age of criminal responsibility for most crimes was 16, and 14 only for the most serious crimes.

The new Criminal Law extended the maximum prison sentence length for juveniles from 10 to 15 years. Many of the children in Cesis Prison were convicted on charges of murder.

INSTITUTIONAL VIOLENCE

In March 2005 a juvenile prisoner was killed by hanging by two fellow prisoners. On July 28, the Vidzeme District Court sentenced both killers to eleven years imprisonment.

Months later at Cesis, in December 2005, a 16-year old boy, upon his return from a Central Prison hospital, was murdered in his cell by two other juvenile cell-mates.

The boys in Cesis Correctional Facility for Juveniles are allowed a bath once a week, every Wednesday. © Christian Als / GraziaNeri

According to Latvian law the juvenile prisoners are entitled to at least one short visit by relatives or other persons once a week for up to one hour in the presence of a prison officer, and one phone call a week, not shorter than five minutes. But the prisoners rarely get in touch with the outside world. © Christian Als / GraziaNeri

Every Wednesday the inmates have free time for a couple of hours in the afternoon, where they have to clean their dorm room, but there are also time to hang out in the court yard. © Christian Als / GraziaNeri

– – –

A Childhood Behind Bars won third place in the PoYI’s Feature Picture Story category, 2008.

Time is of the essence today, so why not a quick look at a mugshot archive?

All these images are from HIDDEN FROM HISTORY. UNKNOWN NEW ORLEANIANS:

“The people grouped here may have had nothing in common except that their lives intersected with the municipality at least once. This exhibit brings them together in part to show how the city classified them. The documents and photographs here are therefore not representative of those New Orleanians who lived their lives quietly and within the law; they are necessarily skewed toward those who erred or strayed, who got caught or got in trouble, or, conversely, those who actively sought assistance from the city.”

The images were selected from the Louisiana Division/City Archives. My favourites here are those photographs in which intriguing, strong(?) communication persists.

– – –

The exhibit was curated by Emily Epstein Landau and funded in part by the Sexuality Research Fellowship Program (1999), a program of the Social Science Research Council, with funding from the Ford Foundation. Dr. Landau received her doctorate from Yale University in 2005. Her dissertation, “Spectacular Wickedness”: New Orleans, Prostitution, and the Politics of Sex, 1897-1917, is a history of Storyville, the famous red-light district. She will be teaching New Orleans history this Spring, as a visiting lecturer at the University of Maryland, College Park. She lives in Washington, DC.