You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Rehabilitative’ category.

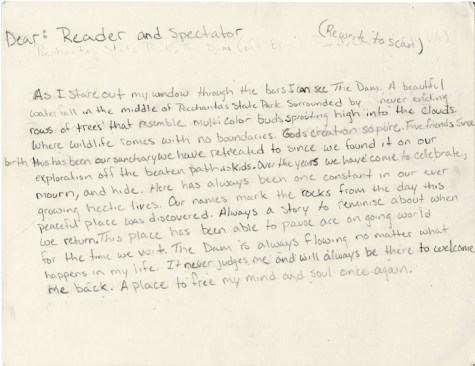

“I see a dam. […] For five friends since birth this has been our sanctuary we have retreated to since we found it on our explorations off the beaten path as kids. We have come to celebrate, mourn and hide.”

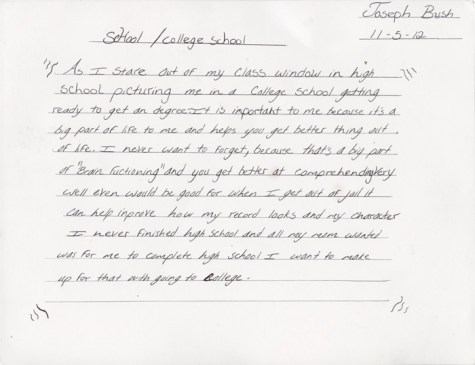

For his participatory project, Some Other Places We’ve Missed artist and photographer Mark Strandquist held workshops in various jails and prisons, and asked prisoners, “If you had a window in your cell, what place from your past would it look out to?”

Along with the written descriptions, individuals provided a detailed memory from the chosen location, and described how they wanted the photograph composed.

Strandquist then photographed and an image is handed or mailed back to the incarcerated participants. The size of photographs he made and later exhibited were/are consistent with the restrictions imposed on pictures sent into prisons.

It’s a strong project that involves many different groups. It attempts to build connections where none exist. If one artist can achieve this, think what a whole posse could accomplish?

NOTE

The scanned letters are difficult to read at this size; I recommend using you COMMAND + keys to enlarge the page and jpegs.

[Keep reading below]

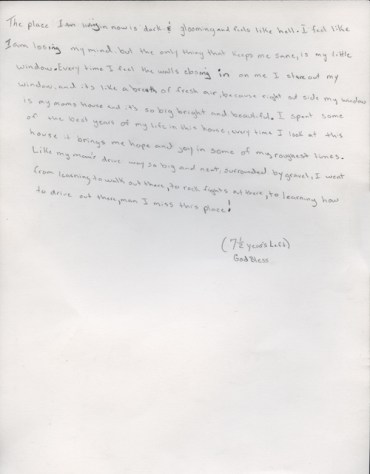

“Right outside my window is my mom’s house.”

“The neighborhood was middle class, nice, where everyone knew everyone. One great lady taking care of us all – grandmother; Big Momma for short. The house set on fire when one cousin playing with matches. Had to move into government owned property. Family split up. Never as close as before. Miss the love. Home base.”

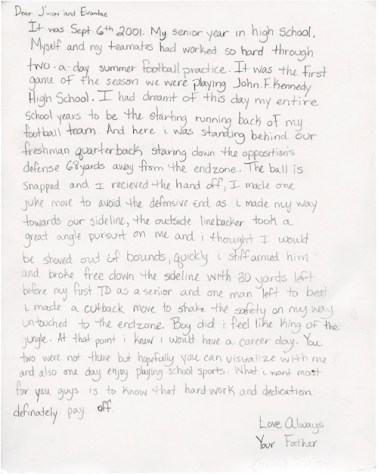

“Here I was standing behind our freshman quarterback staring down the opposition’s defense, 68 yards from the end zone. […] The outside linebacker took a great angle and I thought I’d be shoved out of bounds. Quickly I stiff-arms shim and broke free down the sideline … before my first touchdown as a senior. What I want most is for you guys to know is that hard work and dedication definitely pay off.”

In some ways the work is similar to the Tamms Year Ten Photography Project that asked Illinois prisoners in solitary confinement to describe one image they would like on their cell wall (and which I featured a couple of weeks ago).

Upon encountering the Tamms Year Ten Photography Project, Strandquist was “blown away”, yet he identifies differences between methodolgies.

“The Tamms Year Ten Photography Project is a really challenging project, but there’s so much to love – its diffusion of authorship; its performative aspects of individuals seeking out public spaces to make these images; and its deconstruction of fine art aesthetics,” says Strandquist.

“I believe the form and function of Some Other Places We’ve Missed moves in different, hopefully equally powerful ways. My project is as much about creating a window for the incarcerated participants as it is about creating a window for the public, a meeting ground where each participant’s challenging memories and realities mix with images shot intentionally to facilitate open associations. Part of me wants to hear the stories behind the Tamms requests … but maybe that’s the voyeur in me?” adds Strandquist.

In this case, a will toward voyeurism (to use Strandquist’s term) would indicate that the Tamms Year Ten Photography Project succeeded; it draws audience members in, to then go ahead under their own steam to learn more about the issue, the systems and the people within.

[Keep reading below]

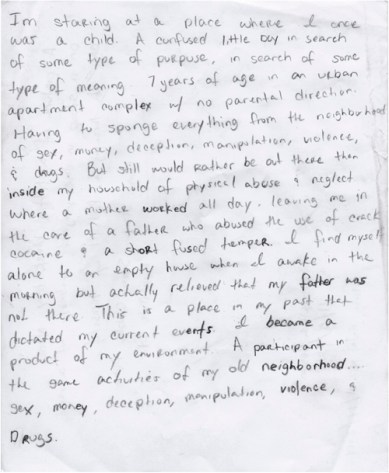

“I’m staring at a place where I once was a child. A confused little boy in search of some meaning. 7 years of age in an urban apartment complex with no parental direction.”

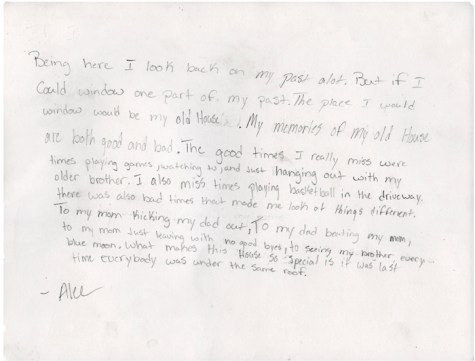

“My memories of my old house are both good and bad. Playing games, watching TV and just hanging out with my older brother. There were bad times that made me see things different – My mom kicking my dad out, my dad beating my mom, my mom leaving with no goodbyes, to seeing my brother every blue moon. What makes this house so special is it’s the last time everyone was under one roof.”

“… all my mom wanted was for my to finish high school. I want to make that up for that with going to college.”

“I miss the feeling of waking up early in the morning to the TV still being on and hearing my little sisters and brothers tearing the house down […] Sometimes it’s the little things that you never pay attention to that can effect you the most in the future.”

GET INVOLVED!

If you, or someone you know is incarcerated, and would be interested in participating in the project, you can email Mark at markaloysious@gmail.com

INSTALLATION

Strandquist recently exhibited Some Other Places We’ve Missed at Anderson Gallery in Richmond, VA. His interactive installation featured weekly prison letter writing workshops and a space to donate books to the local chapter of Books to Prisoners.

Visitors were given the opportunity to take with them copies of written statements by the incarcerated participant about the space to which they wish they had a window.

BIOGRAPHY

Mark Strandquist is a multi-media artist and curator based in Richmond, VA, who creates work that incorporates viewers as direct participants, features histories that are typically distorted or ignored, and blurs the boundary between artistic practice and social engagement. His work has been featured in various film festivals and independent galleries as well as a current exhibit at the Art Museum of Americas in Washington, DC. He is currently working on a BFA at Virginia Commonwealth University. He has a Tumblr.

‘Steph’ © Tony Foushe

There’s two things I hope you’ll carry away from this post. Firstly, the importance of Live Through This a photo series resulting from a-two year collaboration between Tony Fouhse and Stephanie. Secondly, that Tony has established Straylight Press to get limited-edition books and zines in the hands of photo-lovers. Live Through This is Straylight’s first publication.

To regular readers, Tony Fouhse will not be a new name. I’ve always admired Tony’s honest, weekly updates about his ongoing work, emotions and process. In my capacity as a Wired.com blogger, I recommended his blog drool as a top read.

LIVE THROUGH THIS

Four years ago, Tony began shooting USER, portraits of crack and heroin addicts on a single Ottawa city block. During that time, he met Stephanie, noticed something different about her, and asked, “Is there anything I can do to help?” She said she wanted help getting clean.

From that point it’s a long story of great-strides, trauma, dope sickness, humour, sunlight and friendship. Often photographers may distance themselves from the world by saying they’re mere observers. In the case of photojournalism, so-called objectivity sometimes excuses camera-persons from getting involved in even small practical ways to help those they photograph.

Tony is not a photojournalist and he is no hero either; he’s a guy that offered to help someone whose needs were greater than most. If you want to venture into the drool archives, Tony has told the story in great detail. Alternatively, Tony wrote a five-part series about his and Steph’s journey for the ever-excellent NPAC blog [one, two, three, four, five].

In December, Steph had a wobble and ended up in jail. In January, when I read Steph’s words about her court hearing it was clear that Tony has had a life-changing effect on her life:

When I went to Halifax I sat in front of the judge and the crown was asking for 4-6 months and my lawyer asked for probation and sure enough I got it. Then, when I went to Pictou courts my lawyer asked for 6 months house arrest and he got it too […] if it wasn’t for my lawyer in Halifax I would of been fucked. He fought for me to do house arrest because I did so much in the last year, like, he brought up how when I lived in Ottawa I met this man named Tony Fouhse was gonna help me get into a rehab called the R.O Royal Ottawa but I never came to the rehab because I ended up growing a cyst on my brain and how Tony ended up helping me ween from using Heroin to 1 4mg dillie (Dilaudid) a day and sent me home to my family where I could sober up and become a clean mom and we did a project of my life on the street.

It’s a bit embarrassing it’s taken me six months to share my wonder. As well as being photo-rich, Steph and Tony’s journey is a really compelling story. Live Through This is one of the most interesting photography projects I’ve followed in recent years.

STRAYLIGHT PRESS

Live Through This is all the more impressive because Tony and Steph have taken it upon themselves to promote, produce and distribute it. Tony describes Straylight Press as a “vehicle to produce and disseminate printed photo matter.”

Future projects include the unflinching work of Scot Sothern and Brett Gundlock’s Prisoners (which I saluted in the past) so it is exciting times. The idea is that the success of one project feeds the next, so if enough copies of Live Through This sell then profits go into producing the next photographer’s book. It’s a pre-sales fundraising model. In addition, Straylight zines are fairly inexpensive and the intent is to produce 3 or 4 each year.

“Straylight is kind of like a Kickstarter, but with more long-term commitment to projects that aren’t just my own,” says Tony. “Kickstarter projects, while a good and interesting idea, seem to me to be too much about the individual. Not that I have anything against that, after all, you need an ego to be a photographer. But …”

Last month, Tony talked with the Ottawa Citizen about Straylight: Tony Fouhse opens photo-book publishing house – and web gurus be damned.

Tony is flogging prints, books and workshops to raise money for Straylight projects.

Understandably, Tony is shifting his energies from his personal blog drool to the Straylight blog. Straylight is also on Facebook.

Good stuff.

In 2010, photographer Patrick Gilliéron Lopreno visited three Swiss prisons and created the series Puzzle Carceral. Yesterday, I featured a select edit from Puzzle Carceral.

During his year spent on the project, Patrick doubled down on the photo-interventions with a prison photo workshop. Once a week, for two months, he met with prisoners of La Brenaz prison in Geneva. Some of the images are simple point-and-shoot portraits; some are documents of living conditions; others such as the image of an Islamic prayer-mat or the image of a low-lit corridor are more meditative.

I asked Patrick some questions about the experience and he provided a selection of prisoner-made images from the workshop.

Q & A

A workshop is very different to a single photographer, you, making images. What made you decide to put cameras in the hands of prisoners? What were your aims?

The idea was to produce a report with the prisoners on their conditions of detention. What mattered to me was their view of their confinement.

What did they want to do or convey with their photography?

For them the workshop was primarily a time of separation from their prison life. I did not claim to provide them with training and that was clear from the outset. Some men realised that they were able to make beautiful images and for once they made something others could compliment; they became creative.

What negotiations did you go through to conduct the workshop?

The social worker of the prison has helped me tremendously. She brought me into contact with inmates who wanted to participate in this workshop. I never asked for money from the prison for my class because I did not want to be paid. I wanted to stay as independent as possible and retain complete control.

Is a camera not a security hazard inside of a prison?

A camera in prison is never welcome – not for the prison [administration] or for the prisoners. I was not there to make pictures for the inmates’ files. I always asked each prisoner’s permission to use his image.

What stood out about the prisoners work? Any photographs that surprised you?

I was dazzled by the artistic and poetic qualities of their pictures. The best photos were developed and printed on large sheets and then exhibited in the prison.

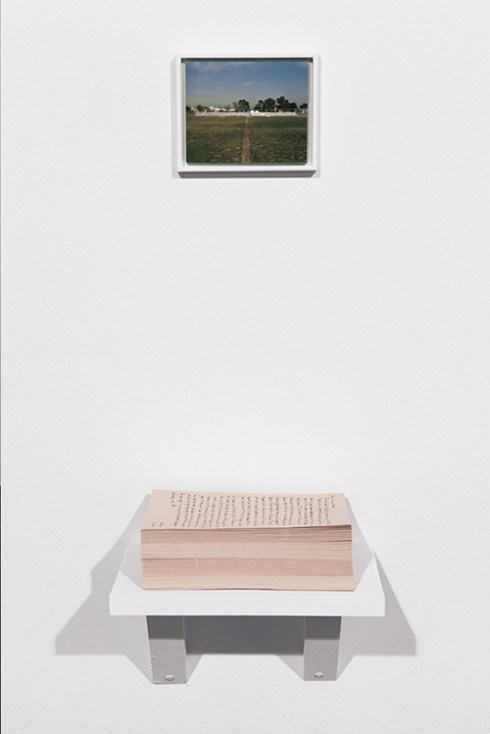

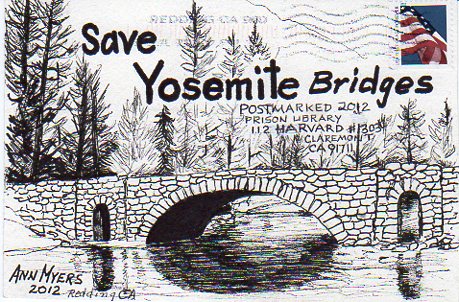

The Prison Library Project will be having a mail art exhibition in October 2012 and invites inmates, families and those who look to improve the lives of those incarcerated to participate:

The Prison Library Project receives hundreds of letters every week from inmates across the country. These letters requesting books and dictionaries, are often beautifully illustrated. In the spirit of these talented prison artists the Postmarked show was created, using the envelope as a canvas to create and share mail art.

The art of letter writing and the use of “snail mail” is on the decline, a casualty of the electronic age. But who among us does not smile when we received a letter in our mailbox? Who doesn’t thrill to find art instead of junk mail and bills? The Postmarked show is a chance for all of us to reconnect with the magic of “snail mail” while helping a population whose voice, if heard at all, is limited to the humble envelope, letter and pen.

Interested participants may decorate, illustrate or create art on an envelope and mail it in for the Postmarked mail art exhibition and fundraiser. Send submissions to:

Postmarked 2012

Prison Library Project

112 Harvard #303

Claremont CA 91711

Entries must be postmarked by September 30, 2012.

Only the side with the official USPS Postmark/barcode will be displayed. Mail art may be painted, stamped, collaged, printed, decorated or constructed. It may be any shape and size that will go through the mail and receive an official postmark.

“Mail may get worn or torn through the mail, but the handling process is an important part of the theme,” says organiser, Rachel McDonnell

Mail will be opened only by the person who purchases the art envelope.

Exhibition: October 5 – November 2 at the Claremont Forum Bookshop & Gallery. Opening Reception: Friday, October 5 Final Bid Party: Friday, November 2, 6:30 – 8:00pm

For more information, see PLP’s Postmarked blog or contact Rachel McDonnell at rachel@claremontforum.org

The Prison Library Project is a prison book and literacy program which sends thousands of books, study aids, educational and spiritual resources to inmates nationwide.

Artist’s impression of projected cellphone imagery.

ART

Stop, a video installation will put faces to the numbers – hundreds of thousands – of people who are unjustly detained by police.

Stop is proposed by New York based Dread Scott and by Joann Kushner, an artist working in Liverpool, UK. As described by Dread Scott:

“Stop will be a projection of portraits of several youth from East New York, Brooklyn and Liverpool, UK. Brooklyn will be on one wall and Liverpool will face them on the other. The life-sized projections will stand and face each other, the audience will be in the middle. Over time, each of the young adults will reveal how many times they have each been stopped by the police during their lifetime. The youth will be having a virtual “conversation” across an ocean with each other as well as with the audience.”

PHOTO

Yesterday, I posted a long conversation with Nina Berman about Stop & Frisk. Berman had not found any other fellow photographers working on the issue of Stop & Frisk. I found one other photographer (who’s work is ongoing and wishes not to publicize it yet) and one artist – Dread Scott.

Dread’s a lovely guy; I’ve written about his work on the prison industrial complex before and I interviewed him last year during PPOTR. Here’s what he says about this Stop & Frisk and this project:

“Last year, New York police stopped almost 700,000 people as part of their “Stop and Frisk” policy. The overwhelming majority, about 90%, were doing nothing wrong at the time and were completely innocent. Most were young and Black or Latino. A similar policy exists in Liverpool and developed after NY police chief William Bratton was invited to be a consultant in another UK city, Hartlepool, in 1996.”

It should be added that UK Prime Minister David Cameron wanted to appoint Bratton as Commissioner of London’s Metropolitan Police Service following the London Riots of August 2011. Cameron was later overruled by Home Secretary Theresa May, who insisted that only a British citizen should be able to run the Service.

Dread has led photography and art workshops with young adults from East NY Brooklyn (a neighborhood with one of the city’s highest police Stop and Frisk rates) and Joann has been working with similar youth in Liverpool. Using cell phones, students have made a powerful series of photographs about their neighborhoods and lives.

Stop will be exhibited in Rush Arts Gallery, NYC from September 13th, 2012.

START KICKING

Kickstarter has definitely reached its saturation point; The Onion’s take made me laugh hardest.

But you don’t even need to feel guilty about this one; Dread’s already reached his target (sure, he’d like a little extra: who doesn’t?)

What’s more important is the message of his work. Until now, I’ve never seen connections made between the US and the UK – between New York and Liverpool – over the Stop & Frisk issue. The issue is rarely framed within the context of youth; we don’t think of the victims as kids … but in many cases they are.

Stop & Frisk is a canary issue. How the controversy resolves itself will be an indication of whether we have progressed; if we are interested and involved in the welfare of others, or if we remain indifferent. It’s driven by Homeland Security dollars and it messes with peoples’ lives. It’s born out of a divided society, just as prisons were. Now the heavy-handed response is on peoples’ doorsteps.

Nigel Poor (left) and Doug Dertinger (right).

The intersection of photography and prisons doesn’t always manifest as a photographer pointing his or her lens at incarcerated people.

Photography – or more specifically the discussion of it and associated issues – can enter relationships, education, exchange. Both the practice and theory of photography can be taught and learned within prisons.

Last September, Nigel Poor, Associate Professor of Photography at California State University, Sacramento contacted me to tell me about her volunteer role teaching the History of Photography at San Quentin State Prison. I was blown away. Never before had I come across a photo history class taught behind bars. Immediately, I made arrangements to meet Nigel and her co-teacher and fellow CSUS professor Doug Dertinger.

As faculty, Poor and Dertinger adapted their existing CSUS syllabus, covering photography from 1970 to the present. However, the California Department of Corrections understandably wanted veto power over slides presented during the course.

Depictions of drugs, violence, sex, children, nudity are problematic for prison administrations … “Which is about 95% of photography,” points out Poor.

Poor and Dertinger were helped out by the experience of Jody Lewen, director of the Prison University Project at San Quentin. Lewen is insistent that PUP teachers do not self-censor, but respectfully present their preferred teaching material and allow the burden – and justification – for any censorship to fall upon the prison administration.

The interaction, therefore, was unorthodox but successful: Poor presented her entire 12 week course to Scott Kernan, Under Secretary to the CDCr (now retired) and to Mike Martel, the then Warden at San Quentin … in two hours!

Of the entire course, only four images were deemed unsuitable, a surprising but pleasing result that Poor describes as “a triumph.”

With Poor focusing on portraits and Dertinger focusing on land use and media, they quickly schooled their students in line, formal composition and leapt from there into sophisticated readings of images.

“I told them the photograph is like a crime scene,” says Poor, “and it is ours from which to draw evidence.”

Poor and Dertinger talk about what a life-affirming experience teaching inside proved to be; about how the men in San Quentin were the “most present students” they’ve ever taught; how invigorating it is to have a passion that isn’t only about oneself; and about the responsibility to educate people in free society about the potential of incarcerated people, a “veiled population.”

“They were ready to travel,” says Dertinger of the students’ willingness to unleash their own emotions and imagination upon photographs read.

Interestingly, the idea that the photograph was not – is not – a reflection of truth was disconcerting for the many of the students. Obviously, the reliability, or not, of narrative and testimony may have had a more profound effect on the reality of their lives as compared to others not subject to the criminal justice system. If you can’t use the language of truth and reality when discussing photography (popularly considered to be objective), then can you use those concepts when discussing your own life?

We end the conversation on a high note: One of the students wrote a comparative analysis of Richard Misrach’s Drive-In Theatre, Las Vegas and one of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theatres. He wrote a 9-page essay during a four-week solitary confinement stint. He concluded Misrach’s work is about space; Sugimoto’s about time.

So impressed were Poor and Dertinger they got the essay into Misrach’s hands … and he read the essay to an audience of 2,500 at the November Pop-Up Magazine Event in San Francisco.

LISTEN TO OUR CONVERSATION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE

© Richard Misrach. Drive-In Theatre, Las Vegas, 1987

© Hiroshi Sugimoto

Dress, Burgu #325 Tirana, 2008 © Annaleen Louwes

In the Spring of 2008, Dutch photographer Annaleen Louwes was artist-in-residence at Ali Demi Women’s Prison in Tirana, Albania. The prison welcomed Louwes as part of a wider philosophy of rehabilitation. “Louwes’ portraits constitute a diary of individuals, without emphasizing the circumstances or context in which these women live,” says the website of the Albanian Directorate General of Prisons.

“She shot photographs every day and brought prints the next day. So the group of women who wanted to come to the little photo-studio she installed in the library, grew day by day, ” says FOAM Magazine. “They started to ask her to reproduce the pictures they had of their mother or lost child. She got a very intimate view on their lives in that way. At the same time she became their photographic tool and they made all kind of collages with the photographs she had made and they already kept.”

At the end of the two month residency, Annaleen presented the series Burgu #325, in For Those Who Cannot Enter, a joint-exhibition with her fellow artists in residence.

All in all, this seems like a remarkable “intervention” with art into this particular penal site. Not only did the women gain rehabilitative worth in the act of photography, they gained actual commodity value in the photographs. This value was eventually cashed in for emotional attachment when the photos made it into the hands of distant family members.

Furthermore, female prisoners from Ali Demi were granted a 2-hour day-release to visit the show at Galeria Zeta!

In thinking about Louwes’ work, my thoughts return once again back to the logistics of a photography workshop inside a prison. I’ve learnt that photo workshops used to be common in America, that they still continue abroad (Louwes being one example) and they occasional crop up in juvenile detention facilities in the U.S. today. But they have waned, disappeared.

I don’t expect prison administration to offer day leave to prisoners to see final artworks in place, but I would encourage them to think of the rehabilitative value of photography and self-representation behind bars. And to think about workshops.

Hair, Burgu #325, Tirana, 2008 © Annaleen Louwes

The Tirana Institute of Contemporary Art (TICA) operates a rolling Artist-In-Residence (A.I.R.) program. For the fourth A.I.R. (April and May, 2008), alongside artists Yllka Gjollesha & Syabhit Shkreli, Annaleen Louwes worked in I.E.V.P ‘Ali Demi’ Prison, Tirana.

A.I.R. #4 was made possibly with the support of FONDS BKVB of the Netherlands and the support of Ms. Marinela Sota, Director of Ali Demi. The resulting exhibition For Those Who Can Not Enter was on show at Galeria Zeta, May 27 – June 20, 2008.

Amy Elkins invited me to curate an online exhibit for Women in Photography, a group now under the umbrella of the Humble Arts Foundation.

My choice of twelve female photographers – Jenn Ackerman, Araminta de Clermont, Alyse Emdur, Christiane Feser, Cheryl Hanna-Truscott, Deborah Luster, Britney Anne Majure, Nathalie Mohadjer, Yana Payusova, Julia Rendleman, Marilyn Suriani, and Kristen S. Wilkins – are a eclectic mix of artists with different approaches to photography in sites of incarceration. Among their works you’ll find fine art documentary, found photography, alternative process, painted photographs, collaborative portraiture, dreamy landscape, photojournalist dispatches and social activism.

Some ladies’ work I’ve featured before on Prison Photography; some are relatively new discoveries; others I met during Prison Photography on the Road; and a few are included in the ongoing Cruel and Unusual show at Noorderlicht.

Thanks to WIPNYC co-founders Amy and Cara Phillips for providing an avenue with which to disseminate photography that counters stereotypes and informs audiences of lives behind bars. Thanks also to Megan Charland for formatting the exhibition.

From my curatorial statement

In the past 40 years, America’s prison population has more than quadrupled from under 500,000 to over 2.3 million. This program of mass incarceration is unprecedented in human history. Women have born the brunt of this disastrous growth. Within that fourfold increase, the female prison population has increased eightfold. You heard right: women are incarcerated today at eight times the number they were in the early 1970s. Are women really eight times more dangerous as they were two generations ago?

Please, browse the gallery, bios and linked portfolios.