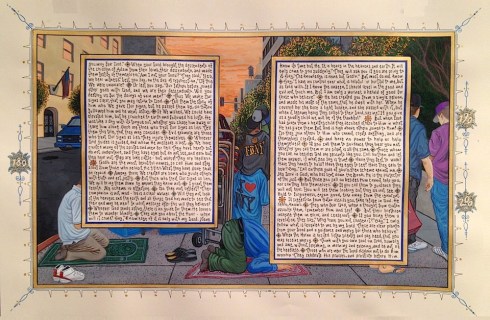

Grey Mountain, artwork by Chip Thomas © Erika Schultz

Just got in from the NW Photojournalism meet. Room chock full of talent including Matt Lutton (of Dvafoto fame) Theo Stroomer, Tim Matsui, Ken Lambert, David Ryder and John Malsbary.

Let me track back a week though.

SOME THOUGHTS AND CONTEXT ON NAVAJO GRAFFITI

A friend of mine who I’ve seen only twice in two years visited Seattle last weekend. He’s Native American … what white folks would call Navajo, but what he refers to as Dineh or Dine (pronounced d-Nay). We were talking about youth culture on the reservation and I mentioned passing through Window Rock (a junction with two gas stations, some vernacular murals and loose packs of dogs). He tells me I was in the wrong part of Navajo Reservation …

Anyway, the murals had me thinking. I saw graffiti on Navajo land – some of it good, some of it terrible; some of it lazy tags, some of it a bit more invested – and I wondered about the social context of these scrawls, paintings and artwork. I proposed to him that a long term photography project NAVAJO GRAFFITI could capture these temporary art interventions. The project would include interviews about the grafs and the social strata from which they emerge. It seemed like it could be a meaningful, novel photography project, a stellar book. Maybe?

In my mind (a place I often invent projects I’d like to see and promote) I envisioned image-making that could incorporate the narratives of a marginalised people without relying on cliches of documentary photography. The grafs could be photographed in the medium format stillness that is all too often wasted on garages, topiary and mall parking lots.

Just a thought.

Thinking on, my friend was as stumped as I to think of any photography work that the Navajo had been able to present, let alone self-represent.

BACK TO NW PHOTOJOURNALISM

The co-organiser of NW Photojournalism is Erika Schultz a PJ at the Seattle Times. When I got home, I checked out her blog. On which, I was blown away to find graffiti on Navajo land. I’d call it street art, except there’s only the open Black Mesa surrounding.

Grey Mountain, artwork by Chip Thomas © Erika Schultz

The work is by Chip Thomas an artist, self taught photographer and Health Services Physician who has lived on Navajo land for 16 years or more. He may not be Navajo by blood but I can be quite certain he has the rights of the Navajo/Dineh people close to his pounding heart.

I want to see more of this. I am not a photographer. Why aren’t photogs out on Native American lands finding more nuanced ways of telling the stories of the people?

The only Native American photographer I’ve identified is Tom Jones of the Ho Chunk Nation, and he is a long, long ways from the Western Deserts; of a different people.

So, two things: 1) Tell me about more Native American photographers (I want to stand corrected) and 2.) Somebody consider a project along the lines of NAVAJO GRAFFITI (I would if I could, but I don’t know cameras).