You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Angola’ tag.

David, DJ at the prison radio station holds a Polaroid of him and his wife. He said the picture was taken more than 15 years before, when he was 18 and she was 16 years old. During his hour as DJ he played mostly Gospel and Christian music at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, June 27, 2000.

Photographer, writer and psychotherapist Adam Shemper and I talk about his portraits and photographs from Louisiana State Penitentiary.

LISTEN TO OUR DISCUSSION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE.

At the age of 24, Adam was challenged (almost dared) by a family friend to “experience something real.” The friend offered him an introduction to warden Burl Cain and the test to photograph within Angola Prison.

We all have difficulty putting our work out in the world, and Adam found that after his nine-month stint at Angola he had more questions than answers.

For many years the work remained unpublished and Adam’s own justifications for the work unsteady. We discuss the life-cycle of the photographs, the reactions of the prisoners to Shemper and his work, and generally, the responsibilities of photographers toward their subjects.

In photography, as in life, it is all about relationships and positive connections that benefit all parties.

Victor Jackson, cell block A, upper right, cell #4. He had ‘I Love U Mom,’ tattooed on the inside of his right forearm. Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000.

LaTroy Clark, cell block A, upper left, cell #6, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Don Jordan reads the Bible in his cell, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Jonathan Ennis puts a puzzle together of a farm scene in Ward 2 of the Louisiana State Penitentiary hospice at Angola, March 21, 2000.

A man sleeping during the day in the main prison complex, camp F dormitory, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, February 1, 2000.

Henry Kimball and Terry Mays in cell block A, upper right section, cell #15, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, September 6, 2000.

Brian Citrey, main prison, cell block A, upper right, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Nolan, a prison trustee, standing in front of the lake, where he often spends his days fishing. He caught catfish and shad on this day for the warden and his guests. Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, June 27, 2000.

Man cuts open sacks of vegetables to sort through, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, June 27, 2000

After chopping weeds in the fields, men wash up as they transition back to their cell blocks at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000.

Men housed at prison camp C dig a ditch at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, January 31, 2000.

All images © Adam Shemper.

Images may not be reproduced elsewhere on the web or in print without sole permission of the photographer, Adam Shemper.

© Adam Shemper

Photographer: Adam Shemper

Title: ‘In the Wheat Fields, Louisiana State Penitentiary, Angola, Louisiana’

Year: 2000

Print: 9″x9″, B&W on archival paper.

Print PLUS, self-published book, postcard and mixtape – $325 – $BUY NOW

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Another incredibly beautiful and difficult image has been made available for purchase to funders of my Prison Photography on the Road proposed road-trip. This time by photographer and psychotherapist Adam Shemper.

I first discovered Shemper’s work in the Mother Jones feature, Portraits of Invisible Men: A photographer’s year at Angola Prison. Shemper describes how he responded to the frequent question for inmates, “What are you doing here?”

I answered that I’d come to make their largely invisible world visible to the outside. I said I wanted … to reconnect them in a way to a world they had lost. I talked of the prison-industrial complex and the deep-rooted inequalities of the Southern criminal justice system. (Almost 80 percent of the inmates at Angola are African-American and 85 percent of the approximately 5,100 prisoners are serving life sentences.) But as I spoke of injustice, it was obvious I wasn’t telling them anything they didn’t know from their daily lives.

Eventually I stopped trying to explain what I was doing. I simply kept taking pictures.

Chaperoned by a prison official at all times, I visited dormitories, cellblocks, and even the prison hospice. I photographed prisoners laboring in the mattress and broom factories, the license plate plant, the laundry, and in fields of turnips, collard greens and wheat.

BIOGRAPHY

Another day, another Kickstarter incentive to peddle.

Frank McMains‘ B&W digital print on archival paper (8″x12″) is available at the $100 funding level. And I’ll throw in a postcard from the road and the PPOTR mixtape (CD). BUY NOW.

You can read more about Frank and the AABA in Exclusive: Photos of the Angola Amateur Boxing Association, Louisiana State Penitentiary, previously on Prison Photography.

Visit Frank’s website Lemons and Beans to read more about his time photographing the AABA.

In the management of prisons, fighting is an activity prohibited by the authorities (bar some exceptional instances) and a sign that the regime and control measures are failing. However, at Louisiana State Penitentiary (commonly known as Angola), the Angola Amateur Boxing Association provides equipment and space for prisoners to spar and bout. From the Louisianan Dept. of Corrections website:

“The prison’s boxing program sponsors “fight night,” held every few months with boxing teams from other state prisons competing for corrections department championship belts. The Angola Amateur Boxing Association has held more belts in all weight classes through its 25-year history than any other prison boxing club in the state. The organization is a member of the Louisiana Institutional Boxing Association.”

In February of 2010, Baton-Rouge based photographer Frank McMains went to Louisiana State Penitentiary to document the club, the fighters and a bout. I asked him a few questions about the experience. [Underlining added by me]

How did you hear about the boxing club?

I had heard about prison boxing through another photographer who had attended a bout at a different prison in Louisiana. Oddly enough, he went without his camera. There is also a documentary about a volunteer boxing coach at Angola and I happen to know the guy who put that together. In short, among those who are interested in such things, boxing at Angola and intra-prison boxing between different prisons in Louisiana is somewhat widely known.

Did you do the story on assignment or of your own volition?

These shots were taken because of my interest in Angola and my interest in the boxing specifically. I pitched it to a few national magazines and one picked it up, but the folks at Angola were uncomfortable with the magazine that was interested in running the photos and article. They felt it was not a serious enough venue for the subject, so the photos remained un-published.

How did you gain access?

Angola is surprisingly accessible for a maximum security prison. I can’t say I have tried to get access to any others, but my sense is that they welcome outsiders who want to report on what is going on there. Over the course of several articles about different activities at Angola I have built a relationship with some of the wardens and staff. As a result, I didn’t really have to negotiate for access so much as plan around their schedule. Recent funding cutbacks meant that Angola’s boxing team did not fight teams from other prisons as they had in the past. There just wasn’t the money to transport the prisoners. So, the whole program was kind of in flux for a while, but once they confirmed a date, I wasn’t going to miss it. The staff at Angola are very professional and they are clear about what sort of interactions you can have with inmates as well as what sort of things you can bring into the prison. I have had my gear searched before but the prisoners who are allowed to participate in events like the rodeo or boxing matches are ones the prison administration feels are less of a threat. They basically would not let you into an area with prisoners who they didn’t trust and they also wouldn’t let someone into the prison with a bag full of gear with whom they didn’t feel comfortable.

How many individuals were involved?

There were about eight bouts so that means 16 boxers. However, there were about 150 prisoners who were there to watch the event and cheer on their friends. In the room with us there were probably four guards who sort of came and went as well as a few staff members and the warden with whom I was acquainted.

How did the prisoners talk about the AABA? Had it changed their behaviour or outlook?

One of my real regrets about this project is that I didn’t get a chance to talk to the boxers in more depth. As they were warming up for the fights they were focused on the what was ahead of them and I didn’t want to interfere with that. After the fights were over I spoke with several of the fighters and coaches but it was very informal.

It has been my experience that prisoners are much more interested in talking about where their family might see the photos and things that don’t pertain to their life in prison. Most of the conversations I had after shooting these photos were about people’s families, not about their lives behind bars.

I would like to follow up with the guys involved, but it was sort of outside of the scope of this shoot.

Some people might think boxing is not the right activity for prisoners; that it is violent. What would you say to people with these reservations?

Some people will always object to boxing as a brutal activity whether that is in prison or in Las Vegas. I get that objection, although I see it as graceful and pure in a way that many sports are not, but you can’t deny that it is violent. Last I checked that was a component of the human condition.

When it takes places in a prison I think it is understandable that some people would balk at what could be construed as violence piled on top of violence. It has been my experience that anything that the prisoners get to do is a step towards socializing them and giving them some hope in the face of a pretty bleak future. Angola has an unusual approach to punishment; they try to engage the prisoners in as many activities as possible. The prisoners work the land there to feed the prison population, they maintain the facilities and even staff the prison museum and gift shop. There is also a prisoner run newspaper and radio station. So, if you remove the fact that it is boxing from the equation then I think that an approach to incarceration that does something other than let people rot away in a cell is a good thing; boxing is a commitment to rehabilitation.

The other aspect of life at Angola is that most of the prisoners will die there, simply put. Most are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole. I understand the punishment-as-vengence argument that some might have. It is understandable to look at a murderer and say, “Who cares if they have any dignity.” I think the staff at Angola see a path for redemption for the prisoners that runs through many different courses. It might be boxing, it might be prison ministry. They seem to think that engaging the prisoners is preferable for all concerned to treating them as de-humanized creatures who simply have to be warehoused until the end of their days. From that perspective, Angola seems to run pretty well. Less than a quarter of the inmates are housed in cells and they spend their days working to make the prison run. That, to me, speaks for itself.

Did you get any sense of what the boxers wanted from you as a photographer? Did they want to convey any message to the eventual viewers?

Yes, every time I have photographed at Angola it is pretty clear that the prisoners want to be portrayed as retaining some of their human dignity. Beyond that, they long for connections with the outside world, their family in particular. You can’t forget that the prisoners at Angola have committed horrible crimes, but it is hard to not feel some sympathy for the incredible loneliness and isolation they all seem to share. Maybe they deserve that, it isn’t really for me to say what justice should look like.

How was, and how is Angola? What’s the culture like? How is it perceived?

All of my experiences at Angola have been unsettlingly mundane. In my mind, I expected to see prisoners rattling tin cups on metal bars and walking around in leg-irons or something. But, they are mowing the grass, cooking food, painting buildings, essentially participating in their own, highly-unusual little community. When people think about Angola, if they think about it outside of the rodeo, it seems that they imagine a dreary place of routine horror. I am sure that it is rough out there, very rough in many respects. But, it does not have the feeling of an armed camp where gangs are pitted against each other, where races are seething to tear into one another or where the guards are everywhere searching for escape tunnels. It’s culture will confound your expectations. Or, it did mine anyway. I didn’t grow up with any sense of prison life outside of film and television. If Angola is anything, it is unlike those scenes from popular entertainment. That is not to say it is bucolic or some penal Club Med. It is a sad but necessary place where the passage of time and the intrinsic nature of humanity do not conform to the normal rules.

It seems there have been many photographers who’ve shot at Angola (I might go so far to say it is the most media-present prison in America). Would you agree? What would one attribute that to?

In a word, yes. It is a thoroughly media documented prison. I think that is for two reasons. First, it is highly unusual in its approach to incarceration as I have spelled about above. They just do things differently there in terms of engaging prisoners rather than just warehousing them.

Secondly, it seems that the administration at Angola, starting with warden Burl Cain and running all the way down, are genuinely empathetic to the prisoners. They know that some of them have been changed, and perhaps redeemed, by the way Angola does things and they want people to know about it. I think they are also keenly aware of how the lack of hope not only destroys the human spirit but also makes prisoners much more difficult to handle. If the prisoners have a reason to get up in the morning then they see a value in toeing the redemptive line that Angola is pushing.

The staff know it is expensive and pointless to incarcerate grey-haired old men who are no longer a threat to society. It seems that Angola is trying to re-humanize prisoners in the eyes of the general public in an effort to change the way our legal system approaches punishment and justice.

Thanks Frank.

Thanks Pete.

_________________________________________________________

Frank McMains is a jack of many trades. He’s got a lot of Flickr. I thank Frank for his time to share his work and thoughts. You can read more about Frank’s time photographing at Angola at his own website Lemons and Beans.

Angola prison rodeo © Sarah Stolfa

Philadelphia based photographer Sarah Stolfa, best known for The Regulars, a portrait series of punters at the bar she tended, has posted some new work on her website.

Pallbearers struggling with a casket, an elegantly dressed African-American lady with a gun holster, a man with a singed blanket stood in a charred field, a long-limbed man with leather bible, public urination, public housing; this is a visually uneasy but coherent edit and presumably the result of a road trip.

Also included are two photographs from the prison rodeo at Louisiana State Penitentiary (one and two). I am uncovering more and more photo projects from this particular event and I’m still working out what, if anything, this relatively high level of exposure means within the specialist sub-sub-genre of prison photography.

Damon Winter emailed me this week to let me know he’s been tinkering with his website. Since we spoke last [here and here] about his ‘Angola Prison Rodeo’ series, he’s revisited and re-edited.

http://www.damonwinter.com/ > STORIES2 > 5 > ANGOLA PRISON RODEO

The image above is new and one of Damon’s preferred images.

Also since then, Winter covered Haiti. It was his first work in a disaster area. This week, Winter’s Afghanistan i-Phone images hit the front page of the New York Times – Between Firefights, Jokes, Sweat and Tedium (James Dao, November 21, 2010)

On those i-Phone Hipstamatic App shots … three things.

1) David Guttenfelder did the same thing earlier this year with a Polaroid App.

2) The simple i-Phone angle is not a story. Judging by the cursory Lens Blog entry, I think James Estrin and Winter might have known this.

3) I’ll pass on the i-Phone photos. Mainly because these have got a stupid amount of attention; attention that should be going to Winter’s videography and incredible number of stories in his short time in Afghanistan.

Damon, I still love your portraits and I still dig your work!

ELSEWHERES

I’d also like to recommend my interview with Winter (for Too Much Chocolate) about his career trajectory.

ONE BIG SELF

I have told many people in person that Deborah Luster’s One Big Self is the most impressive prison photography endeavour to date. I have been slow to state as such on this forum because the scope, details and inspiration of the project are so overwhelming.

Every portrait deserves an essay, but that obviously is not possible. Rather than delay any further, my aim here is to present many of Luster’s portraits, describe the bare facts, and provide some further resources to understand the work.

THE FACTS

Completed between 1998 and 2003.

Portraits taken in many different prisons – mens and womens facilities; minimum to maximum security throughout Louisiana; and with different levels of supervision.

Tens of thousands of portraits taken.

Luster estimates she gave away 25,000 portraits to prisoners over the course of the project.

Luster worked fast – 10 to 15 portraits per hour. At a point working in sheer volume became the only reasonable way to respond to the size of the prison population with which she was engaged.

BACKSTORY

Luster got involved in this longitudinal study through a chance request. Luster’s emotional standing at the time of beginning was – is – atypical and unexpected.

Luster’s mother was murdered in 1988; “Although I was interested in photography prior to that time, I didn’t study or practice it. I began photographing in response to her murder.”

Luster did not deliberately go in search of the subject. In 1998, she was driving near Lake Providence, Louisiana when she came upon East Carroll State Prison Farm. She literally knocked on the front gate. There and then Warden Dixon gave her sanction to begin the endeavour.

VIDEO & AUDIO

SFMoMA has done us a great service in recording and publishing the following video shorts.

In four videos, Luster describes the ORIGINS of the project, elements of ACCIDENTAL PERFORMANCE, printing on ALUMINIUM PLATES, and comments on INDIVIDUAL WORKS.

Remarkable tales.

RESOURCES

Deborah Luster is represented by Catherine Edelman Gallery, who present the best online selection of her portraits.

Good background information is provided by Doug McCash of the New Orleans Times Picayune; David Winton Bell Gallery at Brown; and Grace Glueck of the New York Times.

In 2000, One Big Self was exhibited at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, providing an overview and gallery of the project.

INTERVIEW

The best in-print interview with Luster is included in recent publication, PRISON/CULTURE (City Lights), which I reviewed two months ago.

THE BOOK: ONE BIG SELF

The book is at a premium now and you’ll struggle to find it for under a $100. It is published by Twin Palm Press.

IMAGE/WORDS

Luster collaborated with writer/poet C.D. Wright. Luster’s images and Wright’s poetry are a great complement to one another. Listen to Wright read her poetry from the project.

A PROJECT ONGOING

Despite the passage of seven years since the projects official closure, Luster’s career continues to be defined by her ground-breaking, genre-defining project. Her lectures are vital in that she describes the many facets of the project – from security arrangements, to gear (she generally worked with digital), to processing (she made use of tintype imitation technique printing onto small metal sheets), to the specifics of exhibition.

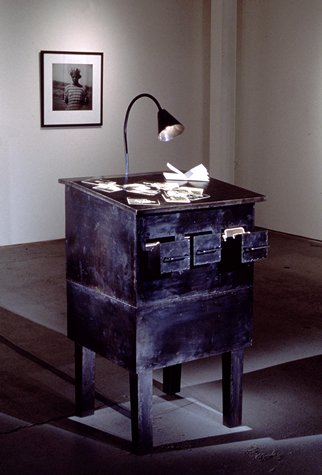

The image below shows a steel cabinet and lamp (containing 288 silver-emulsion aluminum plates) as it was displayed at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and other institutions. Luster wanted to create a tangible viewing experience in which the audience were required to handle the archive of human life in the same way the state of Louisiana organised and disciplined the bodies under its supervision.

In the video (below) Luster talks us through the senses and noises of the exhibit design.

Louisiana has the highest rates of incarceration of minors of any state in the country. Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate per capita of any state in the country.

It has now become the first state to sue its own death row inmates:

via Solitary Watch.

The absurdity of this gesture is fitting for a policy that only ensures time and resources are wasted on arguing the merits for and against killing people for symbolic purposes.

Get beyond the obvious – that is that the state shouldn’t be involved in de-existing people – it seems the main conclusion to be drawn is that hundreds if not thousands of jobs rely on the self-indulged death-industry toying with the fate of death-rowers for decades.

It seems to me that victims, victims’ families and those sentenced become a secondary concern; an infrastructure of legal jousting imposes itself, acquires its own logic and fights it out because that what the cogs demand. The results are laughably tragic deadlocks and bizarre gestures such as that of suing convicted individuals who are virtually powerless anyway.

My solution would not be to limit the legal avenues of appeal following conviction, it would be to abolish the death penalty as a sentencing option.

Just as the state should not be involved in killing people, it should not be involved in the retaliatory-posturing concerning the killing of people.

_________________________________________________

Previously on Prison Photography: There is a lot of inequalities within Louisiana’s criminal [in]justice system, that I have touched upon here, here and here. There’s also chinks of light in an unforgiving system such as radio and football programs at Angola.