You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘CDCR’ tag.

California Institution for Men, Chino, CA. August 2009 riot aftermath. Credit: CDCR

THE OFFICIAL

The California Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation (CDCr) filled the visual hole left by the absence of press photography. I discovered via the CDCr Twitter stream that it had a Flickr profile and more than 72 hours after the event published these images. I use them throughout this post.

THE UNOFFICIAL

I was also contacted by a friend who also happens to have worked in CDCr facilities, is a PP guest blogger and now qualified fact-checker!

He was able to offer some clarification, correction and background on the physical environment at Chino and the CDCR desegregation policy that news sources and I referred to as a factor in the heightened racial tensions. Read on.

Spatial Orientation

The CDCR picture used in the original post shows only the minimum [security] facility at California Institution for Men (CIM). From the picture’s POV, the entire Reception Center infrastructure is behind you. That’s where the riot happened. Nothing happened anywhere in the area pictured.

The large building in the foreground is the administration building for the entire prison. The large building directly behind it is the prison hospital – yes, this is one of the rare prisons that actually has its own hospital. To the right of the hospital is the main walkway toward the back end of the minimum facility and in that upper left corner is a Substance Abuse Program yard with its own dorms and programming facilities. The large baseball field is considered the main yard.

California Institution for Men, Chino, CA. Credit: CDCR

Implementing CDCR Integration Policy

The integration/desegregation issue has not been raised or put into effect in any prison except two – Mule Creek State Prison (MCSP) in Ione and Sierra Conservation Center (SCC) in Jamestown. These were the so called pilot programs for housing integration.

Like all things in CDCR, the reality is not what you think. These two prisons were chosen because they would seem to cause the least possible problems. MCSP is entirely SNY (Sensitive Needs Yard) with only a few hundred general population inmates in a separate minimum facility, and that’s designed for support of the prison itself. Inmates from that population work in administrative areas as clerks, porters, landscapers, etc. Some are sent out to work in local parks, on roads, etc. And some are bussed each day to the training academy for officers in Galt. Almost all of them are within a year or two of release and aren’t interested in getting into any trouble. Anyway, the three SNY yards house about 3600 inmates (1200 on each yard), and they are all in cells and already fully integrated because they are SNY. (Those not in cells are in badly overcrowded gyms and dayrooms.)

Many on the Mule Creek SNY yards, about 1500, are rated EOP mental health inmates (enhanced outpatient program – the most serious level of mental health programming). Virtually all of those are on psychotropic drugs of one sort or another and are essentially in la la land most of the time. Another several hundred are considered CCCMS (correctional clinical case management system) inmates. Some of those are on drugs, and all are doing some sort of mental health programming (support groups, etc.). There is a mental health staff there of about 150 people. Anyway, inmates in this prison are already quite docile and have been de facto integrated for a long time (since it was made SNY three or four years ago). They have had no discord around the housing integration issue that I’m aware of.

California Institution for Men, Chino, CA. August 2009 riot aftermath. Credit: CDCR

California Institution for Men, Chino, CA. August 2009 riot aftermath. Credit: CDCR

Now, Sierra Conservation Camp (SCC) is a different situation. Half of that prison is a [lower security] 3-level SNY facility, and integration in that half is no issue. [But] the general population side of the prison is a different story.

There is a 1-level yard with about 1200 inmates in dorms. An identical 2-level yard is next to it. The mission of these yards is to train inmates to be firefighters and to staff the small fire camps around the state. It’s hard and dangerous work, but the rewards are substantial. The food in the camps is excellent, and there’s as much of it as you want. The pay is very good (by inmate standards) and some have been able to accumulate a parole nest egg of several thousand dollars. Finally, good time credits mean your in-prison time is as little as 35% of your sentence so you can get out a lot earlier. These inmates are typically not the most violent offenders, although some will have violence in their past. Some are affiliated and active gang members. (On SNY yards there are no active gang members, in theory anyway, because you can’t get to an SNY until you renounce your gang.) The housing integration flies in the face of the gang conventions so it has caused some problems at SCC on those two general population yards.

California Institution for Men, Chino, CA. August 2009 riot aftermath. Credit: CDCR

The CDCR started the integration effort last summer, and it quickly backed off when inmates put up resistance. Summer is not a good time in prison; heat makes violence flare more easily. Also, it’s fire season and the camps must be staffed. So they waited until the fall and tried again. Many dorms had mini-riots as gangs instructed incoming inmates not to comply. There were a couple of yard-level disturbances. The inmates tried refusing to come out of their dorms for a couple of days. They believed the officers would bring food to them as they would in a lockdown situation. When they did not, the stomachs settled it temporarily. Eventually, the administration settled on dealing with the situation by depriving any inmate who refused a bunk assignment of privileges. He would be given a disciplinary writeup and not be allowed phone calls, programming, visits, etc. It is currently this kind of a stalemate.

California Institution for Men, Chino, CA. August 2009 riot aftermath. Credit: CDCR

Existing Racial Enmity

One thing that has not been mentioned is the ongoing Black/Hispanic rivalry in the southern half of the state. You may recall in early 2006 there were major riots in the Los Angeles County jails between Blacks and Hispanics. Over 2000 inmates participated, one died and at least 100 were injured. Many men involved in that could be the same people who were at Chino this weekend. Since that part of the Chino prison is a reception center, many inmates were probably local parolees who’d violated. These, and others, would have been through the LA county jail system, probably over the last few years. So this could all be no more than a continuation of the ongoing violence with many of the same people. Who knows!?

I’ve been in those Chino dorms many times and always felt uneasy. Only two officers are assigned, and at any given time one is on the phone or at the door doing an unlock or in the restroom or off on some administrative quest. There is no “gun coverage” as they call it when an armed officer is placed in an elevated position to provide less-than-lethal and lethal force to quell disturbances. As the administrative representative made plain in the interviews, the inmates are really in control. Two officers armed with pepper spray, batons and alarms can be overpowered in seconds. One officer had to be airlifted to medical care from that facility a year or so ago. His partner was doing something and he got hit from behind and they just beat him unconscious. He is extremely lucky he didn’t die; I’m sure the inmates left him for dead. Those dorms are classic World War II era barracks style housing. They would not meet the current standards of prison housing. Actually, they probably would not get any kind of occupancy permit in any municipality in the state.

Conclusion

Finally, a note of purely personal opinion. I believe the CDCR went about integration all wrong. In effect, they asked inmates to integrate. For a year or so prior to the start date, they had meetings with inmates to tell them what it was about and why it was being done. Worst of all, they created a video to sell them on the idea and played it incessantly on the prison TV system. It reminded me of parents who had decided to ask their children to go to school rather than simply telling them to go to school. Inmates are like children, and psychologically, they respond like children. If the administration had simply told them the courts were ordering integration and on a certain date it was happening, I think they would have had less trouble.

California Institution for Men, Chino, CA. August 2009 riot aftermath. Credit: CDCR

Here’s the official CDCr press release update (11th August)

____________________________________________________

Editor’s note: ‘Sensitive Needs Yards’ (SNY) can be understood, essentially, as protective custody areas. They were conceived seven years ago to accommodate the following populations;

1. Guys who had dropped out of gangs. And you have to go through a six-month to one-year deprogramming that includes telling everything you know about the gang and its activities.

2. High notoriety inmates – ex-cops, celebrities, etc. For example, Tex Watson, the Manson family murderer is at MCSP. Phil Spector is on an SNY at Corcoran.

3. Sex offenders.

4. Mental health inmates.

5. Old and infirm people who are still ambulatory.

California Institute for Men at Chino, 2008 (Prior to Riot). Photo Credit: CDCR

Michael Shaw over at the excellent BAGnewsNotes pointed out a rather bizarre anomaly in our image-saturated world. There exist barely any photographs of the prison riot at the California Institute for Men at Chino that occurred this weekend.

Given that Shaw has his hand firmly on the newswire pulse of America I’ll take him at his word … photojournalist coverage of this significant riot was is scant.

I even think that the image Shaw presents is a concession; a still from film footage.

Today, the Los Angeles Times published this image showing the aftermath of the riot.

Photo: A view from outside the fence after weekend rioting at the California Institute for Men at Chino shows a dorm with a hole burned through its roof and a yard littered with mattresses and other debris. Credit: Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times

The BBC was quick to cover the riot. Most news sources framed the riot as a result of racial tension, but in truth those tensions only came to surface due to inexcusable and acknowledged overcrowding. In 2007, Doyle Wayne Scott, a former Texas corrections chief consulting on California prison security reported that overcrowding at the California Institute for Men at Chino created “a serious disturbance waiting to happen.”

Overcrowding is a problem that ignites other problems, and represents a serious issue that has no easy answers. Some prison reform activists would be wiling to see new (temporary) facilities built to ease the tensions, but this is an unlikely scenario as trust between they and the legislature, Governor’s office, CDCr and CCPOA is low. Recent history has taught us that when new prisons are built, they are filled and calls for more prisons follow. The solution is to change the laws that over the past two decades have warehoused increasing numbers of non-violent offenders.

One of the other depressing aspects to this story is that the racial tensions are apparently the result, partly, of enforced desegregation at Chino. Prison populations operate on strict codes and it would seem that top-down-enforcement of an anti-racist policy doesn’t change the attitudes of the men only agitates their existing prejudices, distrust and expected antagonisms toward one another.

My humble suggestion to work against these deep-seated hatreds would be to operate smaller facilities with immediate access to education programs. Sociological models taught as part of a basic curricula are revelatory for many prisoners. Many inmates, given the tools and the logic to explain their oppositions will identify other ways of seeing race.

It is true that some prisoners don’t want to rehabilitate, but they are in the minority. Often it is simply the case that race for this population has never been discussed in complex or nuanced terms.

Here’s some video of the aftermath.

Thanks to Scott Ortner and Stan Banos for the tips on this story.

Joseph Rodriguez‘s work is essential. If I and others can promote his photography humanity then we’ve done some good.

Last week PDN ran a post about the value of the “Digital Curator“. It was a well threaded argument about things we already know: that if an online presence (blogger) does his/her thing for long enough and with a consistent (their own) voice they’ll begin to garner readers, respect and influence.

[WARNING: link blitz, but all justified]

Thankfully, we have (I believe) a healthy photography blogosphere in which plenty of photographers present their own STUFF; megaliths go vernacular; academics question and answer; fine art specialists point us in the direction of good practice & theory; insiders offer editorial, publishing, gallery, collector, buyer or industry viewpoints; universities promote; non-profits take new angles; curmudgeons grumble; old media gets hip; young guns splash out with collective and interview projects & some hover untouchably above.

In September, duckrabbit joined the fray. You may know already, but I am a fan of duck’s blog (by Ben Chesterton). I am not a fan because I agree with everything Ben has to say, but because he says it without frills and then will spend the time necessary to engage the consequent discussions. Such commitment is a priceless commodity.

duckrabbit deals primarily with photojournalism and multimedia and so Ben’s coverage doesn’t always dovetail with the preoccupations of other photographic genres – which is fine, we all have our favourite corners.

To get to the point. I am nodding furiously toward the coverage of Joseph Rodriguez on duckrabbit for three reasons:

1) Because Rodriguez (along with Leon Borensztein) made me realise how vital the relationship between photographer and subject is in creating images. Rodriguez is worth more time than duck or I could ever commit.

2) Because this is the latest in principled stances duckrabbit has taken, AND it happens to highlight the stories of formerly incarcerated.

3) Because I am committed to writing more about Rodriguez in the next month … and need to let you know.

duckrabbit’s first feature of his new series ‘Where It’s At’ (stuff that kicks a duck’s arse) is Rodriguez’s work on Re-entry after prison. Rodriguez worked with Walden House (I remember fondly the stained glass of the San Francisco WH, Buena Vista Park). As duckrabbit puts it, “Rodriguez records lives lived and he never measures the lives of those he shoots against a photographic award, magazine spread or advertising contract. His eye is never on the future, it is always in conversation with the now.”

Go to duck’s post and watch Rodriguez’s 7 minute multimedia piece on re-entry. California is where I cut my teeth in the prison policy and prisoners’ rights fields, so for me, it is especially resonant … and vital.

Also worth noting is Benjamin Jarosch, Rodriguez’s current assistant.

While we are on the topic of different realities in urban America, keep an eye out for this film at your local cinemaplex indie-theatre.

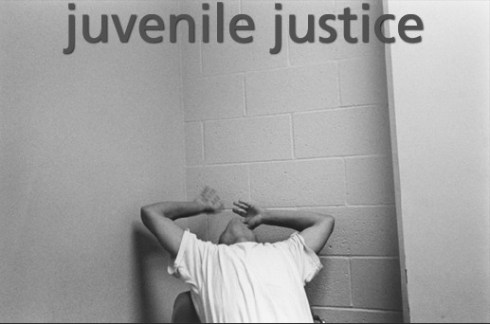

In the next few weeks I’ll be making comment and whirring the brain cogs over Rodriguez’s photographic endeavour Juvenile Justice . Stay tuned.

Rodriguez has won acclaim from all the important people that need to take notice, including Fifty Crows, which incidentally started up a blog recently. Everyone reading this should follow Fifty Crows because they support photographers who get in knee deep … and then some.

Peace.

Yesterday, the internets celebrated Earth Day. The irony in this is that our grandparents’ generation would or could find nothing more incongruous than screen-sucked individuals posting pixels about the earth instead of actually being in its woods, lakes, deserts and mountains. I am not exempt from scorn.

Within the blogophotosphere the general tactic was to post aerial photographies. 100 eyes went to town with a series of Where Am I Now quizettes. NPR went with the easy but stunning option of Geo-Eye’s aerial images. On the aerial theme, i heart photograph posted an unintended but fitting selection of Eva-Fiore Kovacovsky’s photography. The Big Picture did not disappoint with a medley of seriously good environmental issues, opening with a shot of earth from space and Indicommons presented photochroms, albumen & photomechanical prints of nature from earth’s best collecting institutions. And, all of this buttressed by PhotoInduced‘s assertion that digital photography is the green option.

I began to think how aerial photography could tie in with prison photography. Last month, I used some official California Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation (CDCR) images for a post, and in doing so noted the fleeting resemblance of some patterns in the prison-adjacent fields to the salt-pan and tilled earthscapes of David Maisel.

Disclaimer: David, if you are reading, I respect your craft, fine art and politic. In March I camped at Owens Lake and your project formed the basis for much of our camp fire discussion. I hope you don’t think it inappropriate to juxtapose your work with standard state-sanctioned aerial photography.

A CDCR image appears before the text. After the text, images are arranged alternatively beginning with a CDCR image. Any image without a prison is a David Maisel.

___________________________________________________________

David Maisel’s oeuvre is dedicated to altered environmental landscapes. Maisel’s images featured in this article are from The Lake Project which, along with Terminal Mirage, makes up his ongoing ‘Black Maps’ project recording “the impact on the land from industrial efforts such as mining, logging, water reclamation, and military testing.” Maisel’s official bio continues, “Because these sites are often remote and inaccessible, Maisel frequently works from an aerial perspective, thereby permitting images and photographic evidence that would be otherwise unattainable.” Prisons are often remote and inaccessible in California.

In all our justified concern for the environment and its invisible, gradual damages, I also want us to also to consider the invisible, gradual damages done to our social landscape. Men and women are wasted in America’s prisons.

___________________________________________________________

Prison Photography recommends Geoff Manaugh’s extended interview with Maisel at Archinect, audio interview at Lens Culture, Joerg Colberg’s interview at Seesaw Magazine and a full environmentally friendly CV from the Green Museum.

David Maisel was born in New York City in 1961. He received his BA from Princeton University, and his MFA from California College of the Arts, in addition to study at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Maisel was a Scholar in Residence at the Getty Research Institute in 2007 and an Artist in Residence at the Headlands Center for the Arts in 2008. He has been the recipient of an Individual Artist’s Grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and was short-listed for the Prix Pictet in 2008. Maisel lives and works in the San Francisco area, where he has been based since 1993.

It gives me great pleasure to introduce Prison Photography‘s first guest blogger. However, it saddens me as much that he must remain anonymous.

A couple of months ago, I received an email from a California state employee who worked as a prison educator. To paraphrase that initial contact, he stated that “California prisons were places of extreme emotion and stress – due in part to their ‘invisibility’ – and photography within the walls of prisons could go some way in bringing visibility and public understanding to the realities of contemporary prisons.” This was a remarkable statement and the first of its kind that I had heard from someone in employment at a state prison. I asked if he could expand on those thoughts and I am grateful he did.

The great irony of this is that the essay is not illustrated by the images he witnesses daily. He has offered us poignant descriptions of scenes from within prison. The descriptions are a powerful device to get us thinking about what we think we know and what we potentially could know about our penal system.

He suggested I use some of CDCR’s own images. The aerial shots included are the official vision of the California prison system that disciplines and orders the different sized units that comprise the institution; cells, wings, blocks and facilities. The institutional eye of CDCR’s aerial views lies in powerful contrast to the personal narrative recorded here.

Avenal State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

I work in California prisons. Penology has become grown into avocation over the last 10 years. A past career in journalism with some practice in photojournalism informs a strong inclination to report/communicate what I see and experience. So I am daily frustrated by prison policies against recording the visual images I see. Each day I wonder if these policies are justified. If not, are they an impediment to rehabilitation, perhaps even prison reform? Do these policies protect society and the prisoners and staff persons who are a part of society? Or are these policies so much heavy furniture upon the carpeting under which we have swept our societal human detritus?

[IMAGE] There but for the grace of God go I – Close up of a hollow expression on the face of a prisoner as he watches two uniformed guards escort another prisoner across the bare, brown dirt of a prison yard. One guard holds a baton at the ready, the other menacingly waves a carafe-sized container of pepper spray, his finger on the trigger. In the background are multiple 12-foot chain-link faces topped by rounds of glistening razor wire.

North Kern State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

If you ever work with law enforcement on the street, you will hear the mantra “officer safety.” Policies, procedures, even individual officer actions have this mantra as an underlying core within their stated mission to serve public safety. In the prison, that mantra becomes “safety and security of the institution.” Everything is measured against that mantra. Nothing is approved if anyone can show that it may be a threat to institutional safety and/or security. Uncensored and uncontrolled photographic images seem to be considered an inherent threat to institutional safety and security. From a rookie guard to the departmental secretary, few things seem to frighten them quite so much as image impotence in the institutions they so wholly control. From regular staff trainings to informal reminders I have been inculcated (brainwashed?) to accept the imprudence of taking pictures on prison grounds. Simply having a camera on prison property could be cause for termination.

[IMAGE] The burden of laundry – a prisoner wearing only boxer shorts sits on the lowest metal slab of a three-high tier of bunk beds in a prison gymnasium. His hands are deep in a bright yellow, worn mop bucket on the floor in front of him. Inside, white socks and underwear mingle in lukewarm, soapy water.

Prison regulations acknowledge their public nature and the public’s right to know what goes on inside prisons, at least bureaucratically. Title 15 of California Code of Regulations, Section3260 is entitled “Public Access to Facilities and Programs.” It states:

“Correctional facilities and programs are operated at public expense for the protection of society. The public has a right and a duty to know how such facilities and programs are being conducted. It is the policy of the department to make known to the public, through the news media, through contact with public groups and individuals, and by making its public records available for review by interested persons, all relevant information pertaining to operations of the department and facilities. However, due consideration will be given to all factors which might threaten the safety of the facility in any way, or unnecessarily intrude upon the personal privacy of inmates and staff. The public must be given a true and accurate picture of department institutions and parole operations.”

Is absolute control over visual images in and around prison an unreasonable imposition on prisoners, staff, families, general public, media, etc? Does it interfere with the desirable goal of family/community connection with prisoners? Does it contribute anything to either rehabilitation or punishment, the two general goals of incarceration? I’ve catalogued the reasons I’ve been given, or even imagined, over the years and want to see how they stand up to public scrutiny.

Pleasant Valley State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

The first and foremost reason for image control would seem to be the prevention of both escapes and incursions. Photographs of prisons may provide intelligence to anyone planning escapes, contraband smuggling, perhaps even terrorist activities. This seems reasonable enough, at least until you start prowling around the Internet. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Web site has high-resolution aerial photographs of every one of its prisons. Anyone with even rudimentary analysis skills could do serious escape/incursion planning based on these photographs alone. But wait, there’s more. Google maps have more information – local maps, photographs of the prisons, even their “street view” photographs in some instances that clearly show fences, towers, gates, etc. With that level of public information available, I don’t see how you make a credible argument that I can’t take pictures on prison grounds.

5th & Western, Norco, CA. Google Street View.

[IMAGE] The spread – four heavily tattooed prisoners in underwear standing around a dented, dingy gray metal locker. There are bowls on top of the locker and they are sharing food they cooked using hot water, instant soup noodle packets and canned meats, vegetables and seasonings. On the dirty gray concrete wall behind them is stenciled in fading red paint: NO WARNING SHOTS FIRED.

Privacy would seem to be the next strongest argument for prohibiting prison images. Given the open policies in other states, this argument seems flimsy. For prisoners, all conviction information is public. Simply go to the appropriate county court and the information is openly available to the public. Yet it is extremely difficult to get any information about prisoners in the California prisons. For the public there is one telephone number you can call. [916 445-6713] You must know either the prisoner’s CDCR Identification Number or the full name and correct date of birth. The line is perpetually busy and, if answered, the caller can expect to be put on hold for a long, long time (yes, hours). On the other hand, if you go to the Nevada Department of Corrections Web site, you can search for Orenthal Simpson and it will show not only his prison and address but all his convicted offenses, terms and release date. Oklahoma, not generally known for openness, shows the prisoner’s location, convicted offenses, release and parole dates, even pictures. The federal Bureau of Prisons will provide prisoner location and release dates for current and past prisoners. Try a search on their site for Martha Stewart.

Salinas Valley State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

A major defense California prison management will make for the privacy argument is gang violence. They believe if it is easy to find a person in a particular prison, that can make it easier for gangs to use him. The gangs may use the prisoner to do their illegal work or to order him killed if he has fallen from grace, so to speak. CDCR logic is that by keeping prisoners hidden they are keeping them protected. If this is true, the magnitude of the gang problem is nothing short of monumental. Other states apparently do not have this problem. Why not?

[IMAGE] A pile of clothing, denim pants, orange coveralls, boots, etc. on a six-foot folding table. Two uniformed guards on one side of the table. Two naked inmates on the other side of the table, one bent over spreading his rear-end cheeks for officer inspection.

I categorize all other arguments against my taking prison pictures as simple totalitarian need for control. An uncontrolled image is seen as a risk – and why take a risk? The fewer images that exist, the fewer possibilities there are for something to happen that they can’t control. Statistically speaking, very few members of the public or the media ever get to see what happens inside prisons. Media representatives are escorted at all times and only see what prison management wants them to see. They are rarely given unfettered access to prisoners. Visitors are the bulk of the public that see anything of a prison, and that is a very limited view – parking lots, processing rooms and the visiting rooms. Even inmate appearance is tightly controlled in the visiting experience. The prisoner who shows up needing a shave or wearing a wrinkled shirt doesn’t get into the visiting room. And he or she will be strip-searched going in and coming out.

San Quentin. Courtesy CDCR

Prisons, at least in California, are reactive rather than proactive. California’s first permanent prison, San Quentin, opened for business in 1852. Since then, the prison system has been making rules and regulations based on preventing the recurrence of negative events. For example, a prisoner at R.J. Donovan prison at San Diego escaped using a fake staff identification card he had made. He walked out amid a small crowd of other staff leaving at shift change time. As was customary then, he simply held up his photo ID and was waved through with the rest of the ID card wavers. To prevent this from happening again, CDCR policy now requires the gate officer to physically touch and examine the employee ID card before letting the person through the gate. Such policy-creation has been repeated tens of thousands of times over the past 157 years of the California state prison system. It does not lend itself to the openness of unfettered prison images.

[IMAGE] The back of a prisoner’s shaved head as he sits in the audience of a GED graduation ceremony. Visible under his mortarboard are gang tattoos on his head and neck. Blurred in the background an inmate stands at the podium giving his valedictory address.

Until 1980, incarceration in California had rehabilitation as a major goal. The state legislature in that year, bowing to a Reganesque rabble-rousing changed prison law to say the purpose of incarceration is punishment. The concept of rehabilitation disappeared and so did most of the prisoner programming and policies meant to promote rehabilitation. Connection with family is known to be one of the most important factors in rehabilitation. I suggest the control of images in the prison system is one policy that discourages family connections.

Substance Abuse Treatment Facility at Corcoran. Courtesy CDCR

Prison subsumes human beings. Prisoners disappear over time. As soon as a man goes to prison, he begins to fade from his former life. Just as a photographic print will fade over the years, the place of a man in his family fades while he is in prison. Life goes on – without him. His linkages to the fabric of family and community eventually fray and break. Phone calls, letters and visits cannot fully replace the foundations of shared daily interactions, family projects, adventures, challenges and the intimacy of shared emotions. Despite our ability to love, we are creatures of habit, and over time absence can become a habit that seems a normal reality.

The absence of prison images in society supports the concept of shame in incarceration. This shame then supports an estrangement that prison system managers find useful for their purposes. The human toll of that is prisoners who simply hunker down to do their time. Some resist family contact. “I don’t want my children coming to see me in a place like this,” is a common thing I hear from prisoners who could have visits if they wanted them. Would this change if prison images were common in our society? I think so. I think it’s worth a try.

With Emiliano‘s permission I have lifted these images straight from his website. We are working together on an interview for a second post on his work (scheduled for next week). It will include previously unpublished and untouched images from his contact sheets. Please stay tuned for that. Meanwhile enjoy my personal selection of six preferred prints.

ALL IMAGES © 2009 EMILIANO GRANADO

_____________________________________________

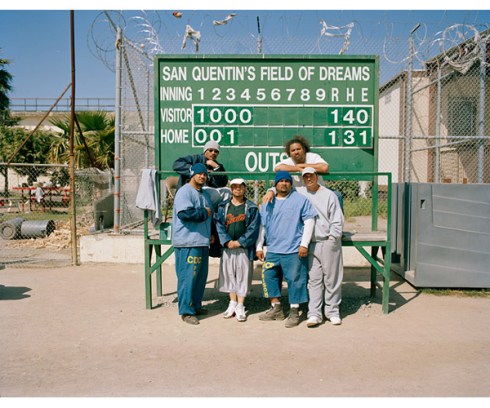

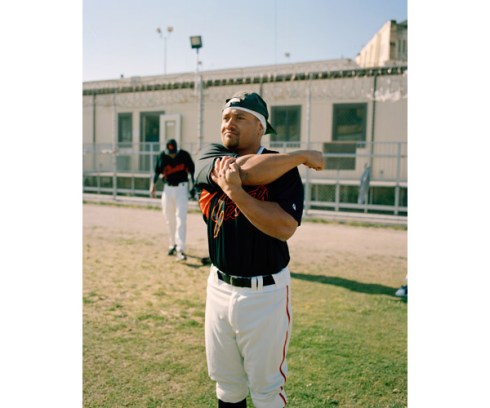

The San Quentin Giants are well known in the San Francisco Bay Area. I have met a couple of guys in the past who’ve played inside the walls during regular season – it is not unusual.

In an ideal world, the to and fro of public in and out of prison would be without restriction, threat or security protocol. This way, society could fear inmates less and inmates would not be institutionalised to the extent they are today.

I realise this is pie-in-the-sky thinking as the minority of seriously dangerous prisoners necessarily dictate the need for stringent controls. Still it doesn’t mean that increasingly trusted and regular contact between inmate and no-inmate populations cannot be our ideal to shoot for. Smaller and purposefully designed institutions would certainly be the first step in this sea change.

The scheduled games for the San Quentin Giants baseball team are the closest approximation to genuine & normalised interaction between inmate and non-inmate populations. When will San Quentin get a basketball team? Or any other teams for that matter?

____________________________________________

Check out these sources for further information on the San Quentin Giants. Press Enterprise – Long Article and Audio, Mother Jones article – Featuring Granado’s photography, California Connected – Video, Christian Science Monitor – Long article and video, NPR Feature – Audio.

And, if you are really engrossed you can always purchase Bad Boys of Summer, a recent documentary from Loren Mendell and Tiller Russell.

If the first post of an anthology is supposed to bear weight then I shall face this expectation head on – in fact I’ll insist upon it. San Quentin was the first American prison I visited. In the summer of 2004, I conducted research at the San Quentin Prison Museum (SQPM), analyzed the exhibits and evaluated its predominant narrative. I found, as with many small museums it suffered from the vagaries of volunteer staffing, poor marketing and unreliable access. Above all, however, the SQPM’s biggest failure was that it employed a historical narrative that ended abruptly in the early 70s and omitted contemporary issues of the California prison system. It was a particularly noticeable failure given the number of problematic issues faced by the CDCR – overcrowding, under-staffing, inadequate health services, dilapidated buildings – and especially noticeable as the named problems were severe-to-acute at San Quentin prison.

The piecemeal SQPM collection was brought together by an appeal and a spirited drive that saw former prison employees alongside local enthusiasts donating artifacts they had acquired in times past. The museum’s narrative ends in approximately 1971 – a year in San Quentin’s history widely considered as its most traumatic. Racial tensions and new variations of Marxism, both inside and outside the walls, were growing and divining credence among disparate groups. It wasn’t so much that the prison, as an apparatus of state, was being called into question; more that the militant Black Panthers, with their cohesive social critique of modern America, led the questioning.

White America didn’t know where to position itself. This was revolution in its most-feared guise and, in so being, paralysed many Americans who were unable to objectively judge the Black Panthers’ arguments.

On the 21st August, an infamous day at San Quentin, George Jackson took over his tier of the adjustment center and attempted an armed escape. The escape failed and he was one of six people who died. The only SQPM artifact to speak of this event was a rifle mounted as centerpiece in a wall-display of weaponry.

This same rifle was discharged by a former prison guard, from the hip, along a tier of cells during the insurrection. It was shot indiscriminately as the guard ran the length of the tier. Of course, the museum label beneath the semi-automatic weapon doesn’t volunteer this information.

The interim president of the San Quentin Prison Museum Association in 2004 was Vernell Crittendon. In mid 2007, Darcy Padilla, a freelance San Francisco based photographer, went to photograph Vernell on his daily duties. The images were to accompany an article by Tad Friend entitled Dean of Death Row in the July issue of The New Yorker. The article does a remarkable job of describing Vernell’s astounding work history, heavy responsibilities, personal amiability and curious (but not fallacious) role-playing. Padilla’s pictures were to accompany Friend’s article, which was and is the most thorough examination of Vernell’s personality, motives and politic. It was a timely piece of journalism as retirement for “Mr San Quentin” approached.

Vernell gave me access to the museum and invited me to tour the prison. He was the only staff member at San Quentin I had any meaningful interaction with, but he played out his multiple roles with aplomb. Vernell was a personal guide and shopkeeper at the museum, historian on the prison-yard, eye witness in the gas chamber, and state department mouthpiece throughout. The first 250 words of my M.A. thesis relied on Vernell as the segue into the issues at, and description of, both the museum and the prison;

Lieutenant Crittendon has thrived as the public relations officer of San Quentin Prison. He is poised, gregarious, proud of office and a great raconteur. His enthusiasm for facts, years and tales of San Quentin blur the man and employee – if a distinction was necessary – and he confesses a long-standing predilection for history.

Vernell is familiar and distant simultaneously. He can always dictate the terms of an exchange but in so doing somehow doesn’t insult his company. Tad Friend, for the New Yorker, expertly summarized how Vernell navigates discussion and parries unwelcome inquiries;

Vernell excels at dispensing just enough information to satisfy reporters, and his sonorous locutions and forbearing gravity discourage further inquiry.

I found myself comforted (never duped) by Vernell’s version of events even when I didn’t believe his words 100%. I always felt that Vernell had said much more by what he excluded and it was my privilege to have witnessed his reticence.

Tad Friend’s economical ten page summary of Lt. Crittendon’s career is, in my opinion, the best reflection of a complex man with shrouded emotions and conflicting duties you are likely to find. What then of Padilla’s task to illustrate the man and the article? She does a fine job. From the evidence of the images on her website (only one of which was used for the article) she had only one window of opportunity on one day to capture her shots. I suspect she shadowed Vernell’s work for a little over an hour for the assignment. Already the odds were stacked against Padilla. We cannot know how well she and Vernell were acquainted beforehand, but prior acquaintance doesn’t necessarily mean an easier time capturing the most faithfully depicting portrait. It is fair to say, however, if Padilla had worked within the walls at San Quentin prison before (which is likely) she certainly knew Vernell. Furthermore, in the interests of another’s professional duties, Vernell was always accommodating.

Judging from the few clues in her principled, varied and continuing series AIDS in Prison, the image below could be from San Quentin. These background hills, however, could as easily be Vacaville or Tracy’s surrounding topography.

Back to San Quentin. Padilla’s San Quentin series captures the solitude of the yard; Vernell is alone in many images. During the days at many prisons the yards are empty. If they are not empty they are more likely being used as necessary routes for groups of traversing prisoners rather than ‘free’ time. When the prisoners are at recreation in the yard (a privilege that differs facility to facility), the staff is at distance unless addressing particular inmate inquiries or directing a group of inmates to their next secure location. Any visitors in the yard at this time (which I have been in San Quentin) are usually following closely the instructions of the guards. Regardless of reasons for being in San Quentin, the slowness of movement from one area to another is characteristic of all people’s experiences. Keys, locks, keys, calls, response, keys, locks, keys.

It is likely Vernell had to hunt out some activity involving inmates to vary the picture content. There is a chronic lack of rehabilitative and counseling programs throughout the stretched CDCR, but in reality, if there is one prison that is trying to counter this trend, it is San Quentin by means of its atypically large pool of Bay Area volunteers, the committed efforts of the Prison University Project (San Quentin is the only state prison that offers a college degree program) and not least the efforts of Vernell himself, “Crittendon helped oversee inmate self-help programs like No More Tears and the Vietnam Veterans Group, and was an adviser to many others. Every other Friday, as the centerpiece of a program called Real Choices, which tries to set wayward urban kids on responsible paths, [Vernell] would escort a group of ten-to-eighteen-year-olds into the prison to meet lifers, who tried to talk some sense into them.”

When Vernell is not photographed alone on the yard (look at the reflection of only him and Padilla in the fish eye mirror) he is taking a back stage to the activities of others. Vernell would not want to interfere in these rare interactions between prisoners and visitors from the outside. Vernell’s approach was typical of a San Quentin staff member; constant observation, constant vigilance and a silent restraint. I rationalized that this was simply a sensible approach – minimize ones own noise and be best positioned to pick up on the small signals/noises around. Words and gesture is used with strict efficiency at San Quentin.

Vernell’s open hand gestures, lumbering gait, deliberate pauses and dramatic referrals to the contents of his satchel are all part of an ensemble he has developed to impose the pace of an interaction and, I believe, to reassure the inmate. He promoted from the ranks of prison guard a long time ago, and so had the benefit of a different type of relationship with the prisoners. He was no longer the enforcer – in truth, he was often the only chance a prisoner had to negotiate a desired variation from system norms. Vernell never did favours per se but he could always see any request, however small, on its own merits. Now he is retired. His formal San Quentin spokesman duties went to his successor Eric Messick. Vernell self-adopted responsibilities were diluted by other staff and may have disappeared altogether. Padilla’s photographs do well to reflect a man carrying out his most unextraordinary job tasks. I think Vernell may be happy that the world has a few images of him to counter those charged press images of him outside the East-gate on the night of an execution.