You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison’ tag.

Saint Valentine was executed on February 14th, 270 A.D. He was a priest in Rome who covertly married couples against Emperor Claudius II’s dictate. Claudius had banned marriage because wedded men were unwilling soldiers and he needed to sustain his warrior-class.

Wikicommons image: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Valentineanddisciples.jpg

The mythology tells us that while in prison Valentine befriended the gaoler’s blind daughter. She brought him meals and they talked at length about imperialism, machismo and state control in the Holy Roman Empire. The night before he was “beaten with sticks and had his head cut off”, Valentine reached through the bars of his cell and touched her eye lids. She could see. It was a miracle. Later that night, Valentine penned a note to his ladyfriend and signed it “From your Valentine”. This was a first.

What next? The civic authorities mopped up the blood and the church went on a propaganda campaign. At that time it was the custom in Rome, a very ancient custom, indeed, to celebrate in the month of February the Lupercalia, feasts in honour of a heathen god. On these occasions, amidst a variety of pagan ceremonies, the names of young women were placed in a box, from which they were drawn by the men as chance directed. The pastors of the early Christian Church in Rome endeavoured to do away with the pagan element in these feasts by replacing the names of maidens with those of saints. And as the Lupercalia began about the middle of February, the pastors appear to have chosen Saint Valentine’s Day for the celebration of this new feast.

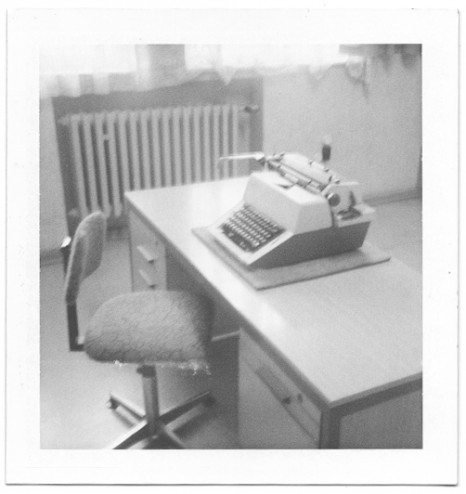

Spurred by the wonderful news over at The Impossible Project that Polaroid Film is getting a second chance, I delved (via its “friends” links) into Polanoid.net. Whereupon, I found this small and particular photo-series by Lars.blumen.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

The Hohenschönhausen Memorial in Berlin is an active community/museum organization that fosters education and understanding with regards political imprisonment. The refreshingly transparent website even concedes crucial gaps in knowledge. “The history of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison site has not yet been researched in sufficient detail. There is, as yet, no general overview detailing the social background of the prisoners, nor the reasons for their imprisonment, nor their length of stay. In fact, we do not even know exactly how many prisoners were kept here over the years.”

I am given the impression a precious sense of purpose & justice drives this shared project. Elsewhere on the site, their call for research is inspiring.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

The reason this set fascinated me so much was that it seemed so immediately incongruous. It is wonderful incongruity. With Polaroid one expects sanctified family portraits (60s, 70s) or blurred disco memories (80s, 90s). Polaroid of the 21st century has been largely an indulgent affair. Lars.blumen has given us a rare treat. He ‘captured’ the most infamous site of Soviet Secret Police interrogation and detention within 10 single polaroid frames.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

Lars.blumen’s project, done without fanfare nor nostalgia, uses the visual vocabulary of the past. Just to make things interesting, the prison (at he time of Polaroid) would never have been observed, nor documented, in this same manner.

The polaroids are remarkable for what they aren’t. They aren’t actual images from the era of the Stasi. And this era is that to which now all energy – as a Memorial – is focussed. The photos are a requiem for the stories and faces of the prisoners never recorded. I think this is why the Hohenschönhausen Memorial has such an emphasis on documenting oral testimony and experiences of prisoners.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

No people, no prisoners, no players in these scenes. The hardware of the site and the illusion of time passed. Understated.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

The texture reminds me of old family portraits in front of the brick of Yorkshire and Merseyside. In front of churches and on door steps.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

Outside are cameras, inside is bureaucracy. Still lured by Polaroid nostalgia, the sinister reality of the images creeps up slowly. The minimalist composition of the Frankfurt school is at use here, but Lars.blumen uses a medium that predates the movement. It’s all very disconcerting.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

Why do I respect these images? Because they are unique and, even to some degree, challenging. I cannot celebrate these images because of their history – they have no history. I cannot celebrate a familiar style – they are recuperations of contemporary German photography. They are idiosyncratic one-offs.

Hohenschönhausen. Credit: lars.blumen

Is it really this intentional? I wonder now if Lars.blumen just had a reel of Polaroid film to burn and that day he happened to be at the Hohenschönhausen Memorial?

If anyone cane help me with Lars.blumen’s identity I’d be grateful!

Official Blurb: The site of the main remand prison for people detained by the former East German Ministry of State Security (MfS), or ‘Stasi’, has been a Memorial since 1994 and, from 2000 on, has been an independent Foundation under public law. The Berlin state government has assigned the Foundation, without charge. The Foundation’s work is supported by an annual contribution from the Federal Government and the Berlin state government.

The Memorial’s charter specifically entrusts it with the task of researching the history of the Hohenschönhausen prison between 1945 and 1989, supplying information via exhibitions, events and publications, and encouraging a critical awareness of the methods and consequences of political persecution and suppression in the communist dictatorship. The former Stasi remand prison is also intended to provide an insight into the workings of the GDR’s political justice system.

Since the vast majority of the buildings, equipment and furniture and fittings have survived intact, the Memorial provides a very authentic picture of prison conditions in the GDR. The Memorial’s location in Germany’s capital city makes it the key site in Germany for victims of communist tyranny.

One last thing. May I recommend you spend time with the lovingly assembled staff portrait gallery at the Impossible Project.

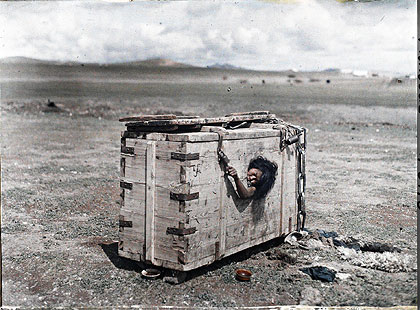

A good friend sent me a link to a Telegraph gallery featuring images from the early 20th century. Almost 2 years ago, BBC4 aired its five-part series Edwardians in Colour. It gave the full treatment to an era distant for most but still within the memory and grasp of older generations.

Stéphane Passet. Mongolian prisoner in a box, July 1913. Image courtesy of BBC. © Musée Albert Kahn

When I see mainstream historicisation as this, I can’t help suspect (just a little) that it is done in order to define the times, facts and lessons of the era. Like all endeavours, it is a play of power (however unintentional). At face, Edwardians in Colour is a noble pedagogical effort and one trusts the BBC to handle the history responsibly. I am no post modernist – I don’t balk at all historical narratives – but I do shrink a little when the writing of history is clearly seen in documentary projects. I wonder if the construction of history in one place means the burying of history somepleace else. Is it the subtlest or the most dogmatic narratives that bed themselves into history? What happens when those with eye-witness testimony pass? Who determines the ‘facts’ of the past?

The Lumiere Brothers marketed the autochrome only a year before French banker and philanthropist, Albert Kahn began his own collection of history colour photography in 1908. Kahn called it the “Archive of the Planet.” The fact that these photographs are brought to us in colour brings us no closer to the times, but I would say they do bring us closer to an appreciation of time. It is a sad appreciation of time, just as the dwindling number of WW1 veterans at war memorials each Armistice Day are a poignant reminder of our dislocation from previous ages. History: How do you take yours? With distant awe or with confident conclusion?

Needless to say, the image above is foreign to us. Without struggle, I would add cultural remoteness to historical remoteness and utterly compound its ‘otherness’.

You can view the original image here, and a youtube video with incongruous funky music here.

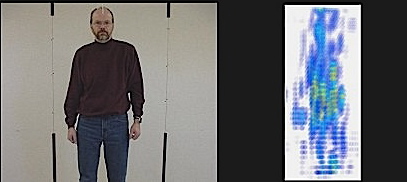

Through the wall surveillance (TWS) is still a technology in it’s infancy, but strategic needs and gushing public awe will perfect this fledgling military toy. It will be driven down marketing channels and into our living rooms. Perhaps TWS, like GPS, will be assimilated into middle class families across America. However, before TWS assumes mass commodity status, I am sure it’s advantages, limitations and in-combat-uses will have been fully tested and exhausted by multiple state and federal enforcement agencies.

Human SAR signatures. Image: Product Information Library, Defense Research & Development Canada

These images are from Defense Research & Development Canada. This model is from the laboratory – probably a scientist. He is not an inmate or prisoner. In 2006, the National Institute for Justice (the research and development agency for the Department of Justice) sought “applications for funding research and development of sensor or surveillance technologies, or novel applications of those technologies, to address specific needs in criminal justice.”

This request included three specific interests: 1) Concealed weapon detection systems; 2) TWS technologies; and 3) “other novel sensor or surveillance technologies, applications, or support functions for specific criminal justice applications.” I guess that third was to keep the DoJ feeling lucky.

Do these images represent a future representation of a prison inmate? Could Prison SERT Teams adopt more surveillance paraphernalia into its existing observational apparatus? Given the opportunity will future media beam TWS images of hostage or seize scenarios, relying on the abstracted “Pixelated Prisoner” to impress the “otherness” – the other worldliness – of America’s incarcerated masses?

California Department of Corrections, SERT Badge

Don’t get me wrong, TWS technologies will be used more widely by agencies other than correctional agencies. One presumes city police departments would want their SWAT teams armed with TWS in hostile neighbourhoods. TWS is of most value in unfamiliar built environments. The prison is ordered and known to the extent that TWS would be needed only in crises such as riots in which prison authorities lose control of buildings or complexes.

Noteworthy of this upturn of interest in – and development of – TWS technologies, is the rabid integration of military strategy into American policing and correctional systems. Should energy and money be spent on equipment that has very limited use? Or could those resources go toward the ‘Research and Development’ of rehabilitation?

Human SAR signatures. Image: Product Information Library, Defense Research & Development Canada

I have found two developers of TWS. The first is the government’s Strategic Technology Office (STO) which is itself a branch of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The second is “your dependable ally” Camero, a private company that has developed the Xaver 400 and Xaver 800. Watch this ludicrous drama presenting the soldier-game applications of the Xaver – try not to be carried away by the macho snare drum and power chords.

My speculations about TWS use in correctional facilities may or may not prove out. I think the need for TWS is so limited in prison environments that it will not be widely adopted. That said, TWS imaging equipment could make future representations of prisoners. I cannot escape the ironic turn this possibility allows. To witness these images is to “see” through the walls – it is a technology that undermines the crude and necessary walls of prison. Appreciating such irony is to understand a power and philosophy that is only interested in making visible the invisible when it is strategically advantageous. Furthermore, this scenario should be interpreted as insidious as it is ironic. In societies of the Supermax, the prisoner is barely evident. The prisoner is not a memory even; possibly a concept. The prisoner is an abstraction, nay, an apparition – a weightless collection of pixels.

Update: Prison Photography collated a Directory of Photographic & Visual Resources for Guantanamo in May 2009.

Guantanamo Prisoner, Political Graffiti. Banksy

Anyone who says the recent media tour of Guantanamo isn’t a public relations exercise by the lame duck has not had their eyes open. Global media were given a tour of camps 4, 5 and 6 at Gitmo and all the footage was screened and vetted before release.

Video: Here is the Guardian’s three minute offering. With any hope Obama will put this illegal operation out of action in 2009.

Artistic legacy of Guantanamo

Guantanamo Protesters outside the US Embassy, London

Meanwhile, we can think of the potency that the orange jump-suit has gained. It’s another icon of the Bush presidency. With regard it’s establishment and its bare-faced operations, Guantanamo was far outside of the public’s imagination. Our culture stomached the guilt and under the Bush administration it was never likely Guantanamo prison would be brought back into line with international law. Activist and non-activist art protested Guantanamo by subverting the camp’s own visual vocabulary.

UHC Collective. "This is Camp X-Ray". Art Installation, Manchester, 2003. Guards with replica guns were on duty 24 hrs and followed a regime copied from media reports.

Back on my home turf in Manchester, UHC, a notoriously bold and inventive art collective, scaled up a version of Camp X-Ray on an unused lot in Withington. It was complete with guard towers, fake guns and orders and activity that replicated the media’s reports of Guantanamo, Cuba. See other UHC Projects here, and read the BBC report here.

Road to Guantanamo (2006). A Michael Winterbottom Film, Spanish Release

And while we are not focusing entirely on photography, slightly off topic with video, I cannot recommend Road to Guantanamo highly enough. The film tells the ridiculous story of three young British-Pakistanis who were in the wrong place at the wrong time (southern Afghanistan, November 2003), and ended up in Guantanamo for 2 years. Your jaw will not leave the floor.

When intellectual withdrawal sets in, I stem the tide and sate the need at a handful of reliable dispensaries. It would seem that two weeks ago, three of my favourite cartophiles (not a word) jumped on the same bandwagon boat. The boldest at-sea-heist of the modern era had just taken place, and it seemed the misfortunes and misadventures on petrochemical distribution routes were top of everyone’s agenda. Spurred by a AP photo in the New York Times (below), the indubitable Brian Finoki focused on the inseparable threads of the pirate clique, theorising that without their vessel, the posse of pirates had only each other to stay afloat in the hard concrete prison yards of Mombasa.

Eight Somali pirates sat at the Kenya Ports Authority Port Police station in Mombasa, where they are being held after being handed over to the Kenyan authorities by the Royal Navy. The eight pirates were arrested, and three others killed, by sailors of HMS Cumberland, as they attempted to hijack a cargo ship off the Horn of Africa. The pirates will be charged in a Mombasa court. Credit: AP

BLDGBLOG was twisting its melon, highlighting improv google map action along with the official sounds coming out of the International Maritime Bureau and its Live Piracy Report. Meanwhile, InfraNet Lab could only conclude that piracy was the opportunist’s career of choice given the current absence of government in Somalia.

I need my own bent on this and so refer you to Jehad Nga‘s phenomenal Pirates Inc. Somalia photo essay depicting pirates under lock and key in Boosaaso Jail & Mandhera Prison, Somalia. Nga is no slouch – he has (largely self-funded) returned to Somalia repeatedly over the past three years. It is incredibly dangerous to work within Somalia. It is more dangerous, in some regards, than in Iraq or Afghanistan where journalists can rely on isolated cordoned-safe-green-military zones and when at large, can work embedded with Western forces. But Nga is no stranger to Iraq either; as foto8 reminds us, “Nga has worked widely in Iraq on assignment for the New York Times. His image of blindfolded Iraqi prisoners arrested by US forces was used as the main publicity shot for the Oscar-winning documentary, Taxi to the Dark Side“.

Pirates imprisoned in Boosaaso's main jail. Photo: Jehad Nga for The New York Times

I would like Nga’s images and words to represent themselves. Words: here’s an indepth interview, from September 2008, with Nga about the situation in Somalia. Images: I have accompanied Nga’s (dare I say it) Carravagioesque prints with his own website commentary about the project:

Nga: Looking over that Somaliland naval map I noticed that the Gulf of Aden (the narrow band of ocean that separates Somalia and Yemen) and the Somali cost line were littered with upward of 100 little skull and cross bone flags. Black flags to denote ships that were successfully taken by pirates and gray for ships that were attacked by pirates but managed to escape. Most of these flags are black.

(Clockwise from Top Left) Mohamed Mahamoud Mohamed; Abdi Rashid Ismael Abdullahi; Farah Ismael Eid; and Abdullahi Mahamoud Mohamed, are each serving 15 years for a piracy conviction. "Believe me, a lot of our money has gone straight into the government's pockets," Farah Ismael Eid said. His pirate team typically divvied up the loot this way: 20 percent for their bosses, 20 percent for future missions, 20 percent for the gunmen on the ship, and 20 percent for government officials. Photo: Jehad Nga for The New York Times

Housed in the Mandhera Prison in Somaliland are 719 inmates 5 of whom are serving 15 yrs sentences handed down to them for their involvement in Somalia’s thriving pirate industry.

Photo: Jehad Nga

The autonomous region of Somaliland is doing their part to combat the growing influx of pirates in the gulf and coastal areas. Utilizing the small fleet of gunboats and navy personnel, they patrol their waters and on occasion escorts’ ships coming in from Yemen. Somalia, in stark contrast to Somaliland, still suffers from the turmoil that has put the country on the map for many people for the last 17 yrs, when the country made a dramatic turn from relative stability to brutal civil war in 1991.

Prisoners. Photo: Jehad Nga

Pensive and quiet the 5 men sat surrounded by prison guards and told their stories of how and why, before one by one they were ushered away and led back to their various cells shared amongst the general population of criminals in the eight block prison set miles out into the arid desert.

In recent months the port town of Boosaaso has also made a name for itself as the kidnap capital of Africa. Previously known best for being the main hub for human smuggling for Somalis eager to flee to nearby Yemen and usually coasting them their lives. With piracy on the rise and stakes getting higher, it is rumored that the money trails lead to some top government officials in the area – due to the large sums of money pirates now demand in return for a seized vessel.

Inside the Prison. Photo: Jehad Nga

Traveling through Boosaaso it is necessary and commonplace to hire a security details consisting upward of 10 local militia to be a deterrent for anyone hoping to cash in on captured a western journalist that, in the past year, has proven to fetch a good price. Maneuvering through Boosaaso we traveled with our rented army toward Boosaaso‘s main jail where currently 100 captured pirates sit out their long sentences or await trial.

In Boosaaso, if the kidnappers don’t find you the extreme heat always finds a way. In an open and shadeless courtyard, two facing jail blocks contain hundreds of prisoners literally caged to bake in the sun. The heat so heavy against your back. It was not only the hope of better pictures that tempted me to enter these filthy concrete boxes, but also escape from the looming mid day sun heavy over head.

"Pirates, pirates, pirates," said Gure Ahmed, a Canadian-Somali inmate of the jail. "This jail is full of pirates. This whole city is pirates." Photo: Jehad Nga for The New York Times

As I approached the iron bars of the blocks movement is heard and then and as came closer murmurs grew into rumbles and further until the deafening sounds of hundreds of inmates came crashing against me like a wave of anger and despair. [They] stretched their arms through the bars inviting us to listen to their stories of how they were dying in this place. Of how each of them was suffering from one disease or another.

Inmates of Boosaaso Jail. Photo: Jehad Nga

Beyond the out reached hands just eyes and parts of their faces could be made out inside the lightless rooms. Figures moving in and out of the small amount of light streaming in from the between the blue painted bars.

A prison guard inside Mandhera Prison. Photo: Jehad Nga for The New York Times

As pirates are proud of their catch so are the guards of these jails. They know that their numbers will remain consistent as long as Pirate season persists in the Somali waters. No slow down is the trend in expected as little international help has been organized, and with numbers of active pirates in these waters continuing to grow even that help seems, in some ways, futile.

View Jehad Nga’s other work at his website

View his New York Times photo essay here

Read an interview with a pirate here

Herman Krieger – stalwart of the Oregon photography community and Eugene resident – is a self-made specialist in the art of captioning. However, more than his quirky words, I appreciate the great lengths he goes to in order to document sites of the prison industrial complex.

View from Boise Gun Club, New Idaho State Prison. Herman Krieger

Krieger described the circumstances of the series, “The idea of making a photo essay on prisons and their settings came after driving from Tucson to Phoenix. The view of the prison in Florence, Arizona struck me as an odd thing in the middle of the landscape. At that time I was only looking at churches for the series, Churches ad hoc“.

With Lifetime Mortgage, Vacaville, California. Herman Krieger

“I then made some photos of prisons in Oregon and California. Others were made during a trip by car from Oregon to New York. I would have made a longer series, but I was too often hassled by prison guards who noticed me pointing a camera at a prison. They claimed that it was illegal to take a photo of the public building from a public road, and threatened to confiscate my film”, explained Krieger.

Room Without a View, Pelican Bay, California. Herman Krieger

Pelican Bay was opened in 1989 and constructed purposefully to hold the most violent offenders, usually gang members. Along with Corcoran State Prison, in the late 1980s, Pelican Bay ushered in a new era of Supermax facilities in California. They are remote (Pelican Bay is just miles from the Oregon border) and they are expansive. Their distant locations prohibit regular visits from inmates’ family members – a detail probably not lost on the CDCR authorities who sought to transfer, contain and stifle the aggressions of Californian urban areas.

Bayside View, San Quentin, California. Herman Krieger

Having lived in San Francisco for three years, the policies, activities, controversies and executions at San Quentin State Prison were always well reported in the Bay Area press. One of the most frustrating repetitions of the San Quentin coverage was the journalist’s compulsion – regardless of the story – to remind readers of the huge land value of San Quentin and the opportunities for real estate on San Quentin Point.

Open for Tourists, Old State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger.

Over the Hill, New State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger

America is a large country. It should be no surprise that prisons are built in isolated areas – it makes economic sense to build on non-agricultural hinterlands and it makes strategic sense to purpose build facilities on flat open ground. More significantly, to locate these “people warehousing units” out of society’s view, allows convenient cultural and political ignorance for the authorities & citizens that sentenced men and women to America’s new breed of prison.

Krieger’s photographs summarise the key intrigues and detachment “we” feel as those excluded from prison operation and experience. Krieger, in some of his other images, gets closer to the prison walls and yet I deliberately featured these six prints precisely because of their disconnect. What terms, other than those of distance and exclusion, can we legitimately use in dialogue about contemporary prisons?