You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Richard Ross’ tag.

Camilo Cruz, Untitled from the Portraits of Purpose series, 56 x 45 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

–

ARE WE HITTING PEAK-PRISON-ART-SHOW?

Of course, I’m being provocative, but the rise and rise of prison criticism and reflection (and commodification) in the cultural sphere bears consideration.

Here is not an exhaustive list but a few examples — Life After Death and Elsewhere, curated by Robin Paris and Tom Williams at apexart; To Shoot A Kite curated by Yaelle Amir at the CUE Foundation; Voices Of Incarceration at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles; Try Youth As Youth curated by Meg Noe at David Weinberg in Chicago; Site Unseen: Incarceration curated by Sheila Pinkel; The Cell and the Sanctuary put on by the William James Association in Santa Cruz, CA; and my own Prison Obscura.

–

This weekend, Inside/Outside: Prison Narratives will end its 10-week run at the Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art at Chaffey College in Southern California. Inside/Outside is a relatively large survey of prisoner art, prison photography and visual activism that brings together the work of Sandow Birk, Camilo Cruz, Amy Elkins, Alyse Emdur, Ashley Hunt, Spencer Lowell, Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD), Jason Metcalf, Sheila Pinkel, Richard Ross, Kristen S. Wilkins, Steve Shoffner, the Counter Narrative Society and students at the California Institute for Women.

It’s a great exhibition.

As many of the names in Inside/Outside: Prison Narratives are familiar, I felt a review by me would be redundant; it’d be dominated by applause to the committed artists I see as asking the right questions … because they’re the questions I’ve ask too.

Instead, I wanted to focus on the recent uptick in fine art exhibitions orbiting the issues of prisons.

Rebecca Trawick, Director of the Wignall Museum and co-curator of Inside/Outside and I were in touch a while before I realised that this should be what we should discuss. And how the cultural production of art around, and about, the prison industrial complex propels, inspires, derails (and much else besides) dialogue about mass incarceration in America.

Kindly, Trawick and her co-curator, Misty Burruel, Associate Professor of Art at Chaffey College accepted my invite to answer some questions. The Q&A is peppered with artworks from Inside/Outside: Prison Narratives.

Scroll down for our discussion.

–

Camilo Cruz, Untitled from the Theater of Souls series, 56 x 45 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Why did you make this exhibition?

Rebecca Trawick (RT): Incarceration was an issue that I kept returning to in my research.

As a curator, I’m specifically interested in shedding light on important but difficult social issues through the lens of contemporary art. I love how artists can take an unwieldly topic and consider it thoughtfully, often personally, and in really compelling ways that allow the viewer a chance at transformation, or expansion of, thought and perspective.

Because we work at an institution of higher education, these exhibitions become a safe space to start difficult discussions about issues such as incarceration, and they become a tool to educate and inform. This kind of exhibition (if done well) can demonstrate the value of art to transform ideas, minds, and communities.

Misty Burruel (MB): Because it was a challenge. On the heels of a number of incarceration exhibitions in southern California that focused on works by incarcerated artists and artists confronting the criminal justice system, it was appropriate to look at it through the lens of education.

We are confronted daily with students that have either been incarcerated or have family who are incarcerated. It was time to have difficult discussions about the role of education in the penal system, our responsibility as citizens to each other, and how parolees reintegrate into yet another system.

Spencer Lowell, La Palma prison, Arizona

PP: Is incarceration a “hot topic” right now? Why?

RT: As Misty and I mention in our remarks in the printed takeaway, we seem to be experiencing a unique convergence of policy discussions in the US as well as popular culture interests, so we feel like the conversation is already happening in certain circles.

We hope our exhibition helps to expand the discussion and dig a little deeper into some of the topics looked at in contemporary documentary (think the recent Vice episode, Fixing the System, in which President Obama – the first sitting US President to do so – visited a federal prison) to the popularity of Orange is the New Black.

MB: Jenji Kohan’s, Orange is the New Black, portrayal of incarcerated women created a splash on Netflix and revealed through mass media the complexities of a system within a system. The women were all too real and relatable. We live in the Inland Empire and have two prisons at our footstep.

PP: California Institute for Men and California Institute for Women.

Jason Metcalf, Cheeseburger, French Fries, Iced Tea (Dwight Adanandus), 2013, archival pigment print, 16 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

PP: Is Inside/Outside about incarceration or is it about the representation of incarceration?

RT: The exhibition is about the many issues surrounding incarceration that we hope our viewers will consider more deeply after viewing the work on view. Issues include the value of rehabilitation behind bars; juveniles in justice; death penalty, segregation, prison labor, and isolation as systems of control, among others.

PP: How did you select the artists?

RT: The Wignall Museum mainly draws from Southern California for practical reasons–funding limits us to local pickups mainly. In some cases (Kristin S. Wilkins, for example) agreed to ship the work to us so we were able to include her. We’re often limited regionally, which explains the SoCal bias. We would have loved to include works outside our region, if possible. (see next question for a list of some we would have included if possible.) The one thing I remind myself is that we’re not trying to be essentialist in what we portray or explore, but rather offer some really amazing work to assist us in digging a little deeper into the state of incarceration today.

MB: We are in a human warehousing gridlock. The works collectively focus on how the system of control does not discriminate (women, men, and youth detention).

Kristen S. Wilkins, Untitled #10. From the series ‘Supplication’ (2009-2014) “Grand Ave. by Shiloh (Cemetery). Left side of water fountain. Has colorful wreath with flowers. It is where my son is @. He is the best thing that happened to me in my life. He was my world.”

PP: Were there any artists or works out there that you’d wanted in the show but couldn’t for whatever reason?

RT: Yes! Many. The list includes Deborah Luster, Dread Scott, Jackie Sumell’s The House That Herman Built, and Julie Green’s Last Supper installation all immediately come to mind. There were many others, but those three stand out for me.

MB: We wanted to have more guest speakers, but funding always seems to be a hurdle. We can certainly look at the issue, but we really wanted to talk about it.

PP: Really? From the outside that you had a phenomenal amount of programming. I applaud you. How important was programing around the exhibition?

RT: Programming is critical. Because we’re limited in many ways in terms of what we can show – due to spatial and fiscal restrictions – programming allows us to bring in experts in the field to further contextualize and expand the themes of the exhibition. It also allows community engagement and for other voices to join in the conversation, often in a public forum. That ability can’t be underestimated, I think.

MB: When the discussing an exhibition about incarceration we were most focused on programming. Rebecca and I are collaborative by nature and we were able to find others who were very interested in asking difficult questions within their own disciplines (Sociology, Philosophy, Correctional Science, Administration of Justice).

© Sheila Pinkel

PP: I’ve been asked a number of times “Who are you (a white, cis-gender, male, college graduate) to speak to these issues?” Every time by a highschooler — God, I love them. Were you ever challenged over your role and/or position while putting Inside/Outside: Prison Narratives together?

RT: As a curator at an institution situated on the campus of a Community College I feel strongly that it is our responsibility to explore a wide array of topics in our exhibitions and to look from a place of diversity – diversity of media, content, viewpoint, race, ethnicity, etc. – and through the lens of contemporary art, but it is critical that we do so in a way that is thoughtful and multifaceted.

Philosophically we try to schedule our exhibitions and programs in a way that expand outside of our own limited perspectives. We also try to use multiple guest voices – guest curators, guest speakers, etc. to expand the discourse around an exhibition. But the long and the short of it is, I try to always be conscious of my privilege and to present diverse voices. That said, my own experience/perspective was never called into question during the exhibition planning or implementation phase.

MB: The college has wholeheartedly embraced the exhibition and its programming.

Amy Elkins. 26/44 (Not the Man I Once Was), 2011. Portrait of a man twenty-six years into his death row sentence where the ratio of years spent in prison to years alive determined the level of image loss.

You’ve said the response so far has been positive. More than other Wignall shows? More among the student body, or beyond? How do you measure response/success?

RT: This exhibition definitely has seemed to link to something that is personal and relatable for many of our students, faculty and community visitors, evident by the verbal responses and reactions we’ve seen in the galleries. We’ve held a number of panel discussions, engagement activities, a film screening, and dozens of tours. Unequivocally, discussions always seem to lead to the personal and comments suggest that the ability to discuss a somewhat taboo topic has been relevant.

MB: This work is incredibly personal and relevant to the Inland Empire.

PP: Can you see the successes and failures of the show already? Or is it too soon for that type of assessment?

RT: Success can be measured in qualitative and quantitative ways … (as of course, can failure). Due to the high level of programming, and the sheer number of student tours we’ve conducted, we can see an increased level of engagement. Our visitor numbers are up, the number of students speaking up during tours has increased a great deal, and the unsolicited feedback from students/faculty/staff we’re getting has been remarkable.

We also ask all students who visit us as part of a tour to fill out a short survey. Results won’t be tabulated until the close of the exhibition, but I feel the results will mirror the anecdotal evidence we’re seeing. As a curator, however, I’m always thinking about what we can improve upon – from the curatorial practice, to layout and installation, to printed collateral and programming…reflection is key.

MB: I think the museum does an amazing job of allowing artists to ask difficult questions and explore relevant social and political issues.

The Wignall Museum hosted workshops and discussion led by Mabel Negrete and the Counter Narratives Society.

PP: Anything you’d like to add?

RT: We hope that Inside/Outside and the many other excellent exhibitions and artists looking at incarceration with a critical perspective will encourage the questioning of the system as it is, and that it might even encourage engagement in our communities in ways that can make real change in the world.

–

Follow the Wignall Museum at Chaffey College on Facebook and Twitter.

If you’re in L.A. this week, get yourselves down to the Billy Wilder Theater at The Hammer Museum, on Wednesday, 29th April for 7:30pm.

Under the ominous title “Human Faces in the American Juvenile Justice Gulag”, Peter Sellars and Richard Ross will be discussing juvenile detention and courts in the United States.

Broadly, they’ll be using Ross’ ongoing project Juvenile In Justice as an entry point to the topic. Ross documents “the placement and treatment of American juveniles sentenced to facilities that punish, treat, confine, assist, and occasionally harm them.”

Tickets are required and available at the Box Office one hour before the program. One ticket per person; first come, first served. Early arrival is recommended. It’s at 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90024. For more information, telephone (310) 443-7000, or email info@hammer.ucla.edu

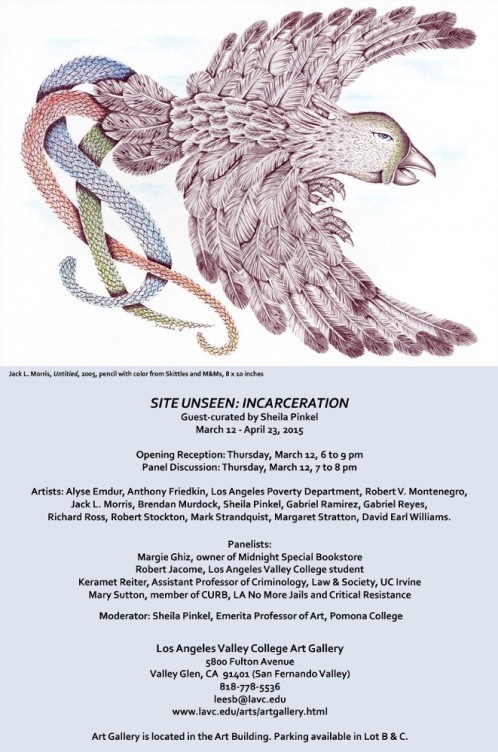

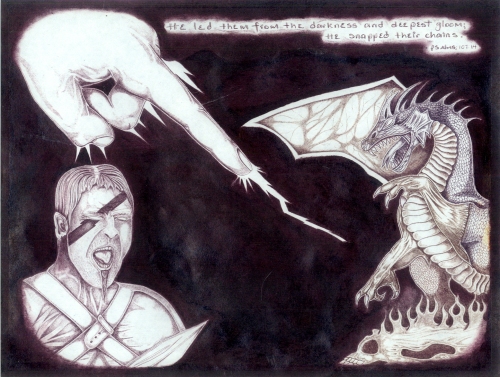

Site Unseen: Incarceration flyer. Featuring the work of Jack L. Morris, a California prisoner who has been in solitary confinement for almost 25 years.

Do artworks made on opposite sides of prison walls work together in a gallery space?

Yesterday, at the Los Angeles Valley College, in Valley Glen, CA the exhibition Site Unseen: Incarceration came down form the walls. It was an exhibition bringing together prisoner-made art with artworks made by outside artists about prisons. (Catalogue in PDF, here)

Some artists I knew — Alyse Emdur, Anthony Friedkin, Los Angeles Poverty Department, Sheila Pinkel, Richard Ross, Mark Strandquist, and Margaret Stratton. Others are new to me — Robert V. Montenegro, Jack L. Morris, Brendan Murdock, Gabriel Ramirez, Gabriel Reyes, Robert Stockton and David Earl Williams.

Shamefully, all those names with which I am unfamiliar I quickly learnt are prisoners. Why shame? Well, it’s all about consistency. I value activism that is built upon close alliance with, and information, from prisoners. There are no better experts on the system than those subject to it. At the very least, I should know and support the leading Prison Artists.

However, when it comes to painting and illustration, I have adopted lazy double standards. Without examination, I have demoted prisoner made art — commonly referred to by the catch all “Prison Art” — to an inferior status. I have prejudged most Prison Art. For my own comfort, I have bracketed Prison Art as naive and limited. I’ve conveniently focused on scarcity of supplies inside prison of prison to cursorily explain the lo-fi aesthetic of Prison Art.

My “logic” blinded me to the invention, resourcefulness and resistance inherent to almost all prison art. Hell, we’ve got prisoners making work out of M&Ms.

Site Unseen: Incarceration, therefore, is a nice kick back in the right direction. If we don’t have prisoners’ own artwork upon which to meditate then we lose site of the issues fast. As much as I have championed the work of Emdur, Ross, Strandquist and the Los Angeles Poverty Department, I want to now celebrate the works of Jack L. Morris, Brendan Murdock, Gabriel Ramirez, Gabriel Reyes and David Earl Williams.

I wish also to applaud Sheila Pinkel for bringing together inside and outside, and for committing the oppressed and their allies to one another upon gallery walls.

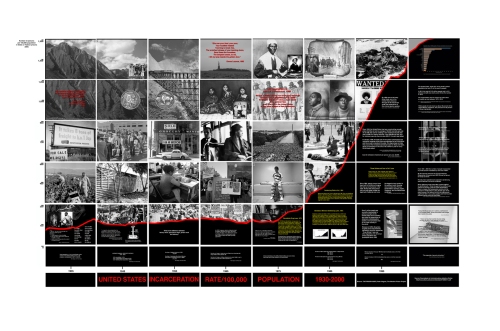

Sheila Pinkel. Site Unseen: U.S. Incarceration (2014). 7’ x 14’ Archival ink jet prints. Pinkel remarks, “Site Unseen: U.S. Incarceration includes the major laws that have resulted in the expansion of the prison system, the Sentencing Reform Act (1984), Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Law (1986) and Three Strikes Law (1994). It is important to note that in the 1960s, during the civil rights era, rate of incarceration was declining as people adopted the ‘rehabilitation not incarceration’ attitude. However, after the Rockefeller Drug Laws took hold, incarceration in the United States began to grow exponentially. Also included is demographic information about the high rate of incarceration of non-white people and women, the great number of people being held in solitary confinement and the massive amounts of money being made by investors in the prison industrial complex. The backdrop for the graph is a set of images from U.S. history taken in the 19th and 20th centuries that reflect the treatment of minorities and prisoners. The poor, non-white and uneducated make up the majority of incarcerated today.

Origins of the Show

In 2004, Pinkel exhibited for the first time her mammoth work Site Unseen: U.S. Incarceration (above). While the shared title between this catalyst work and the exhibition confuses matters a little, it demonstrates the degree to which Pinkel is bound to prison reform. Passion + politics is usually a good recipe for art.

Pinkel’s motivations for mounting the show are many — concerns for Mumia Abu-Jamal’s case; an awareness of slavery (past and present); the doctrines of ownership and manifest destiny; sensitivity to the quiet traditions of aboriginal people; a raised consciousness toward the unparalleled use of torturous solitary confinement; and the profit making industries of the prison industrial complex; and more besides.

The urgent issues within the reform and abolitionist movements are so great that often they can drown each other out, or obscure one another. Perhaps, that is where silent 2D artworks come to play their part. Perhaps, a gallery space in which viewers can mediate their own responses is a hushed but vital contribution to the reform debate?

David Earl Williams. Parrots (1996). 22” x 28” Ball point pen.

It is helpful for me to interrogate the idea that gallery shows and art have an effect upon political realities. I make a conscious effort to justify my workand others’ and to continually ask if analysing images and creative output from prisons changes the daily experience of the United States’ 2.3 million prisoners.

I conclude, often, that conscientious and intellectually honest analysis of images from prisons plays its role in the wider discussion needed to drag us out of this prison crisis.

Prison Sketches in the Absence of Prison Photos

Undoubtedly, in the past few years, solitary confinement has emerged as one of the main, digestible and terrifying issues behind which reformers could win arguments, gain traction and mindshare. The public now know that 80,000 people on any given day are subject to psychological torture within our prisons.

Many of the photographs of Supermax and solitary units — and there are not many — have come about because of court ordered entry to facilities. With the exception of Social Practice make-believe, artists and photographers have, for the most part, failed to image these dark, hidden spaces for the public. I’m apportioning no blame here, just pointing out fact. With that understanding, then, it is significant that the majority of prison artists in Site Unseen are either in solitary or on death row.

Brendan Murdock. Tower (2012). 9” x 12” Linoleum cut print.

One of the artists in Site Unseen is Jack L. Morris, a creative spirit with whom Pinkel has had a lasting personal and professional relationship. In 2011, Pinkel began corresponding with Morris. At that point, he’d been incarcerated for 31 years. In 1978, aged 18, Morris was sentenced to a 15 years to life for being an accomplice to a murder. When the California Department of Corrections (CDCr) opened Pelican Bay Sate Prison (the first state-run Supermax in the nation) in 1989, Morris was transferred. He’s been in solitary confinement since.

“During this time he has not seen sunlight or touched another person,” says Pinkel.

Jack L. Morris. Turtle (2012). Dimensions: 12” x 12” Medium: pen, pencil, peanut butter oil, pastel color.

Pinkel points out that the decision-making power to place someone in solitary is solely in the hands of the correctional officers. Checks and balances against abuse in this ‘Us vs. Them’ equation are largely absent. Pinkel believes that Morris, like many prisoners in the SHU, is subject to a Kafkaesque situation in which solitary is inescapable. While policies are shifting after attention from Sacramento politicians, it remains incredibly difficult to get out of the SHU if CDCr has classed you as a gang member.

“Jack has not been involved in gang activity and has had no ability to be involved in it since he has been in solitary. However, he is repeatedly denied release from solitary and has had his designation increased to active gang affiliation,” says Pinkel. “At the moment, there is no legal way for him to get out and, to my mind, there is no good being served by his continued incarceration, either in solitary or in prison at all.”

Alyse Emdur. Anonymous backdrop painted in New York State Correctional Facility Woodburn (2012). Dimensions:42” x 52” Inkjet print.

Clearly, Pinkel has an affiliation. Put that aside though and consider Morris for his work and you can’t help but be impressed. In order to prevent himself “losing his mind”, Morris created poems, drawing and letters. Pinkel published them in the book The World of Jack L. Morris: From the SHU.

“Together,” says Pinkel, “they form a complex picture of a talented person who believed most of his life that he was not intelligent.”

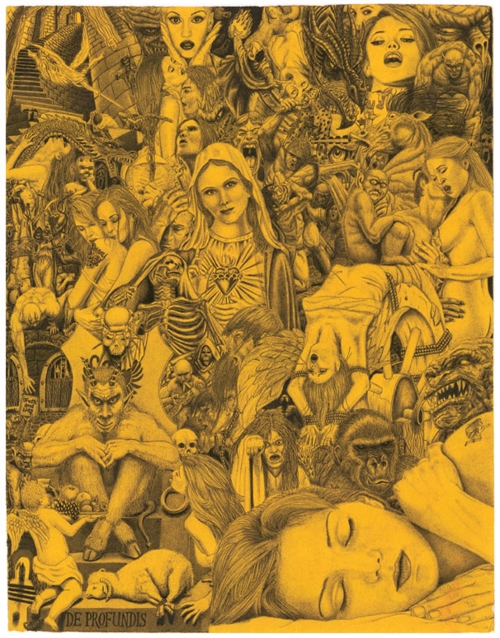

And so we arrive here. At Morris’ and other art from inside. To be mesmerised by the intricacy of the work is understandable, but more-so we should be quietly and slowly scrutinising the work and using it as a gateway to a psychology we must surely hope we, or any of our loved ones, ever come to know.

Prison illustrations work very similarly to photographs in some ways, in that tropes recur and we find ourselves glossing over them. We presume that the system gives rise to them same type of images of flora, fauna, cars, tattoo-inspired designs, versions of women, motorcycles, sad clowns, tears and blood. These things are prevalent, but individual touches exist in the gaps and it is there we may identify the individual artist.

Gabriel Ramirez. De Profundis … Dreams (Before 2007). 11.5” x 15” Medium: Pencil on manilla envelope.

The worst thing prison art and photography, alike, can be is misunderstood as aesthetic cliche and used as excuse to bypass the social conditions from which they arise. Prisoner art from solitary is the most reliable source of imagery on which we can rely to learn about extreme confinement. We just need to give it space to percolate. A gallery can do that.

There’s a perverse clash of time appreciation at work in order for prison art to have an effect. The artist labors for days and weeks on a single piece and goes to great lengths to deliver it outside the institution. On the outside, we’re spoilt for images and it’s almost luck or strange happenstance for us to spend more than a few seconds with an image. But, it is possible and a gallery can do that.

Mark Strandquist. Windows From Prison (2014). Banners 5’ x 11’. Digital prints on vinyl.

Strange Brew

As might evident, I am largely in support of Site Unseen. However, looking over the catalogue, I am a bit skeptical toward the mix of works. Does Mark Strandquist’s work (above) that relies heavily on public education and engagement work when he cannot transform the gallery into a workshop space or collaborate with local reform groups? Are we getting to the point that a prison show cannot exist without the work of Richard Ross!? (I’m friends with Richard and had breakfast with him this morning; he won’t mind the snark). It just seems Ross might be an easy option.

Is Site Unseen a prison art show supported by outside sympathisers, some of whom happen to be artists? Or is it a genuine attempt to level the field and present artists inside and outside as equivalents? The latter is a tough proposition. I have seen it done though. The Cell and the Sanctuary (Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History) managed to knit insider and outsider artists works together, but they managed it effectively because they were all either students or faculty in the William James Association’s Arts In Corrections program at San Quentin. A visual thread ran through The Cell and the Sanctuary that is not as immediately apparent in Site Unseen.

Margaret Stratton. Ship’s Passenger Log, December 1916, Ellis Island, New York City, June 29, 1999, 10:35 a.m. (1999). 16” x 20”. Archival digital print.

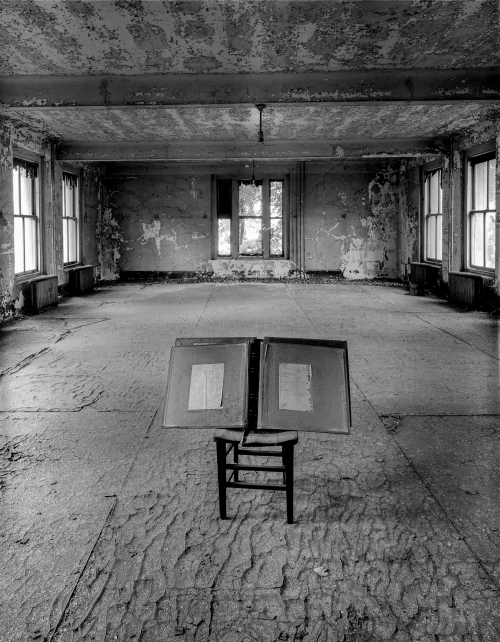

The main culprit, for me, is the work of Margaret Stratton (above). I’ve constantly wondered what use have images of decaying/ abandoned prisons for connecting us to pressing contemporary prison issues. I can find value in most other works in Site Unseen as they’ve a clear umbilical cord to the tumorous, pulsing Prison Industrial Complex. We can sense the toxic bile of the system in the majority of the works. We can wonder at the ability to stay sane and creative from within such a system. I get none of that awe from Stratton’s work.

I understand Stratton’s B&W images employ a different route to the issue and I don’t want to suggest there’s any inherent flaw in the work or its tactics. The fault, if any, lies with the decision to include this type of work that I identify as an outlier within the collected works.

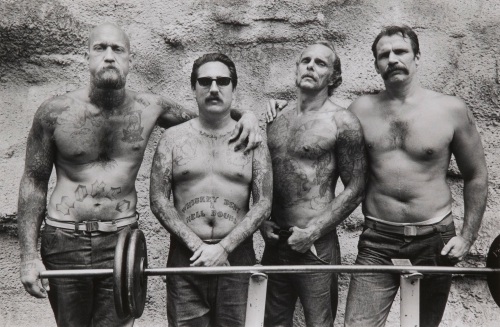

Four Convicts, Folsom Prison, CA (1991). Dimensions: 11” x 14” Black and white gelatin silver print.

Another , but slightly less obvious, outlier is Anthony Friedkin’s photo of four Folsom prisoners in the early 90s. It is a captivating portrait for sure (one that I featured very early on Prison Photography) but it is hardly representative — of either recent photographs from prisons, or the U.S. prison population as a whole. Friedkin is best known for his illuminating access into, and photographs of, gay culture in San Francisco and Los Angeles. His respectful treatment of these derided communities was light years ahead of mainstream political consciousness. Friedkin lived among the LGBQT community and the intimacy and support shows through in his work.

I cannot think that Friedkin had a mere fraction of that sort of access to the prison population. I suspect he made his image above on a single visit to Folsom Prison. I have not seen any other photographs from prison by Friedkin. And so, this image, is neither representative of Friedkin’s work. It is ham, distant and reliant on the tropes of prison cliche. Not only is it out of place, it is out of time.

Gabriel Reyes. Like a Hook (Before 2007). 8.5” x 11”, Ball point pen on paper.

As far as I am concerned, any and all mentions of Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes and the Los Angeles Poverty Department’s performances (below) are absolutely essential and cannot be reiterated enough. Each are powerful statements on the nature of power and the over-reach of state control.

LAPD’s dramatisations are informed by the experiences of people who have been incarcerated and Emdur’s collected portraits and large format photos of prison visiting room backdrops originate from a keen engagements with the visual logic of carceral systems.

Robert Stockton. Fight (Before 2007): 8.5” x 11”. Pen, additional color.

Prisons and criminal justice reform are gaining attention in the news and public consciousness (a good thing), but just because the conversation is being had and the appetite for a show like Site Unseen might be more ready, the challenging logistics of putting together a curated show of this kind remain unchanged. Kudos to Pinkel for bringing togther artists from inside and outside prison invested in the same goal of making the U.S. a less dangerous, punitive and misunderstood place.

At first glance, the mix of ‘prison art’ on one hand and ‘art made about prisons’ on the other might appear incongruous, but that attitude is exposed as flawed very quickly. As the majority of works in Site Unseen emerge as responses to this country’s brutal, class-dividing prison system, I must conclude that they can do nothing but work together. And so must we if we’re to scale back on decades of fear, bad law and failed policy. If you need resolve and fire-in-your-belly for the task then merely look to the work of those who are subject to confinement. You’ll find it, quietly roaring, there.

Of all the prison photographers in all of the U.S., Richard Ross is the probably the best at getting his work in front of eyeballs. I think that’s because he asks a lot and often.And because his images are compelling.

This past week, Ross showcased works form his latest book Girls In Justice on PBS News Hour.

By virtue of the sheer breadth of his survey of juvenile prisons, here’s a case of a photographer actually showing us things we wouldn’t otherwise see. The photographic medium is often hailed as being (almost magically) revelatory, but how often is that actually the case. It’s harder and harder to show people something they’ve NEVER seen before. That’s why closed prisons such as systems provide such an interesting locus for inquiry and why I continue my research.

I digress.

Go check out Ross’ work at PBS, and at the Juvenile In Justice website.

“I’m not a sociologist, I’m just the schmuck on the floor trying to make sense of all this,” says Ross.

–

Also, check out my essay What Are We Doing Here? (cross-posted to Medium) for the current Try Youth As Youth (TYAY) exhibition as David Weinberg Photography in Chicago. Ross is one of four artists in TYAY, a gallery show that is forcing the debate forward, and endorsing the ACLU in Illinois’ latest campaign against trying children as adults.

–

10, 11, 12, 13 & 14. © Steve Davis.

TRY YOUTH AS YOUTH

Currently on show at David Weinberg Photography in Chicago is Try Youth As Youth (Feb 13th — May 9th), an exhibition of photographs and video that bear witness to children locked in American prisons. As the title would suggest, the exhibition has a stated political position — that no person under the aged of 18 should be tried as an adult in a U.S. court of law.

In the summer of 2014, selling works ceased to be David Weinberg Photography’s primary function. The gallery formally changed its mission and committed to shedding light on social justice.

Try Youth As Youth, curated by Meg Noe, was conceived of and put together in partnership with the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. Here’s art in a gallery not only reflecting society back at itself, but trying to shift its debate.

The issue is urgent. In the catalogue essay Using Science and Art to Reclaim Childhood in the Justice System, Diane Geraghty Professor of Law at Loyola University, Chicago notes:

Every state continues to permit youth under the age of 18 to be transferred to adult court for trial and sentencing. As a result, approximately 200,000 children annually are legally stripped of their childhood and assumed to be fully functional adults in the criminal justice system.

This has not always been the case in the U.S. It is only changes to law in the past few decades that have resulted in children facing abnormally long custodial sentences, Life Without Parole sentences and even (in some states) the death penalty. In the face of such dark forces, what else is art doing if it is not speaking truth to power and challenging systems that undermine democracy and our social contract?

Noe invited me to write some words for the Try Youth As Youth catalogue. Given Weinberg’s enlightened modus operandi, I was eager to contribute. Here, republished in full is that essay. It’s populated with installation shots, photographs by Steve Davis, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, and video-stills by Tirtza Even.

–

Scroll down for essay.

–

Image: Steve Liss. A young boy held and handcuffed in a juvenile detention facility, Laredo, Texas.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Image: Steve Liss. Paperwork for one boy awaiting a court appearance. How many of our young “criminals” are really children in distress? Three-quarters of children detained in the United States are being held for nonviolent offenses. And for many young people today, family relationships that once nurtured a smooth process of socialization are frequently tenuous and sometimes non-existent.

–

Try Youth As Youth Catalogue Essay

–

WHAT AM I DOING HERE?

–

Isolated in a cell, a child might wonder, “What am I doing here?” It is an immediate, obvious and crucial question and, yet, satisfactory answers are hard to come by. The causes of America’s perverse addiction to incarceration are complex. Let’s just say, for now, that the inequities, poverty, fears and class divisions that give rise to America’s thirst for imprisonment have existed in society longer than any child has. And, let’s just say, for now, that the complex web of factors contributing to a child’s imprisonment are larger than most children could be expected to understand on a first go around.

As understandable as it might be children in crisis to ask “What am I doing here?” it should not be expected. Instead, it is we, as adults, who should be expected to face the question. We should rephrase it and ask it of ourselves, and of society. What are WE doing here? What are we doing as voters in a society that locks up an estimated 65,000 children on any given night? In the face of decades of gross criminal justice policy and practice, what are we doing here, within these gallery walls, looking at pictures?

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility, Albany, Oregon, by Richard Ross. “I’m from Portland. I’ve only been here 17 days. I’m in isolation. I’ve been in ICU for four days. I get out in one more day. During the day you’re not allowed to lay down. If they see you laying down, they take away your mattress. I’m in isolation ‘cause I got in a fight. I hit the staff while they were trying to break it up. They think I’m intimidating. I can’t go out into the day room; I have to stay in the cell. They release me for a shower. I’ve been here three times. I have a daughter, so I’m stressed. She’s six months old. At 12 I was caught stealing at Wal-Mart with my brother and sister. My sister ran away from home with a white dude. She was smoking weed, alcohol. When my sister left I was sort of alone…then my mother left with a new boyfriend, so my aunt had custody. She’s 34. My aunt smoked weed, snorts powder, does pills, lots of prescription stuff. I got sexual with a five-year-older boy, so I started running away. So I was basically grown when I was about 14. But I wasn’t doing meth. Then I stopped going to school and dropped out after 8th grade. Then I was in a parenting program for young mothers…then I left that, so they said I was endangering my baby. The people in the program were scared of me. I don’t know what to think. I was selling meth, crack, and powder when I was 15. I was Measure 11. I was with some other girls — they blamed the crime on me, and I took the charges because I was the youngest. They beat up this girl and stole from her, but I didn’t do it. But they charged me with assault and robbery too. This was my first heavy charge.” — K.Y., age 19.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

I have spent a good portion of the past six-and-a-half years trying to figure out just what it is that images of prisons and prisoners actually do. Who is their audience and what are their effects? If I thought answers were always to be couched in the language of social justice I was soon put right by Steve Davis during an interview in the autumn of 2008.

“People respond to these portraits for their own reasons,” said Davis. “A lot of the reasons have nothing to do with prisons or justice. Some people like pictures of handsome young boys — they like to see beautiful people, or vulnerable people, whatever. That started to blow my mind after a while.”

My interview with Davis was the first ever for the ongoing Prison Photography project. It blew my mind too, but in many ways it also prepared me for the contested visual territory within which sites of incarceration exist and into which I had embarked. Davis’ honesty prepared me to face uncomfortable truths and perversions of truth. It readied me for the skeevy power imbalances I’d observe time and time again in our criminal justice system.

The children in Try Youth As Youth may be, for the most part, invisible to society but they are not far away. “I was just acknowledging that this juvenile prison is 20 miles from my home,” says Davis of his earliest motivations. If you reside in an urban area, it is likely you live as near to a juvenile prison, too. Or closer.

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Prisoners, and surely child prisoners, make up one of society’s most vulnerable groups. Isn’t it strange then that rarely are they presented as such? Often depictions of prisoners serve to condemn them, but not here, in Try Youth As Youth.

As we celebrate the committed works of Steve Davis, Tirtza Even, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, we should bear in mind that other types of prison imagery are less sympathetic and that other viewers’ motives are not wed to the politics of social justice. A picture might be worth a thousand words, but it’s a different thousand for everyone. We must be willing to fight and press the issue and advocate for child prisoners. Our mainstream media dominated by cliche, our news-cycles dominated by mugshots and the politics of fear, and our gallery-systems with a mandate to make profits will not always serve us. They may even do damage.

Image: Steve Davis. A girl incarcerated in Remann Hall, near Tacoma, Washington State.

Given that the works of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross circulate in a free-world that most of their subjects do not, it is all our responsibility to handle, contextualize and talk about these photographs and films in a way that serves the child subjects most. It is our responsibility to talk about economic inequality and about the have and have-nots.

“No child asks to be born into a neighborhood where you can get a gun as easily as a popsicle at the convenience store or giving up drugs means losing every one of your friends,” said Steve Liss “They were there [in jail] because there was no love, there was no nourishing, there was anger in startling doses, and there was poverty. Tremendous poverty.”

Image: Steve Liss. Alone and lonely, ten-year-old Christian, accused of ‘family violence’ as a result of a fight with an abusive older brother, sits in his cell.Every day the inmates get smaller, and more confused about what brought them here. Psychiatrists say children do not react to punishment in the same way as adults. They learn more about becoming criminals than they do about becoming citizens. And one night of loneliness can be enough to prove their suspicion that nobody cares.

Davis, Even, Liss and Ross understand the burden is upon us as a society to explain our widespread use of sophisticated and brutal prisons more than it is for any individual child to explain him or herself. The image of an incarcerated child is an image not of their failings, but of ours. We must do better — by providing quality pre and post-natal care for mothers and babies, nutritious food, livable wages for parents, and support and safety in the home and on the streets. Most often, it is a series of failures in the provision of these most basic needs that leads a child to prison.

“Poverty would be solved in two generations. It would require an enormous change in our priorities. Look at how we elevate the role of a stockbroker and denigrate the role of a school teacher or a parent, those who are responsible for raising the next generation of Americans,” says Liss.

(Top to Bottom) Installation shot; video still; and drawings from Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez’s Natural Life, 2014.

Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez. Natural Life, 2014. Cast concrete (segment of installation). A cast of five sets of the standard issue bedding (a pillow, a bedroll) given to prisoners upon their arrival to the facility, are arranged on raw-steel pedestals in the area leading to the video projection. The sets, scaled down to kid size and made of a stack of crumbling and thin sheets of material resembling deposits of rock, are cast in concrete. Individually marked with the date of birth and the date of arrest of each of the five prisoners featured in the documentary, they thus delineate the brief time the inmates spent in the free world.

Each of the artists in Try Youth As Youth have seen incredible deprivations inside facilities that do not — cannot — serve the needs of all the children they house. Ross speaks of a child who has never had a bedtime. A social worker once told Davis of one child in the system who had never seen or held a printed photograph.

Documenting these sites is not easy and brings with it huge responsibility. Tirtza Even has grappled with the weight of her work “and how much is expected from them is a little heavy.” In some cases, these artists are the outside voice for children. Liss acknowledges that expectations more often than not outweigh the actual effects their work can have.

“People ask how do you get close to kids in a facility like that. That isn’t the problem. The problem is how do you set up enough artificial barriers so you don’t get too close. So you’re not just one more adult walking out on them in the final analysis,” he says. “I, at least, convinced myself into thinking it was therapeutic for the kids. At least someone was listening to them.”

So far, the efforts of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross have been recognized by those in power. Liss’ work has been used to lobby for psych care and an adolescent treatment unit in Laredo, Texas. Ross’ work was used in a Senate subcommittee meeting that legislated at the federal level against detained pre-adjudicated juveniles with youth convicted of committed hard crimes.

“That’s a great thing for me to know that my work is being used for advocacy rather than the masturbatory art world that I grew up in,” says Ross.

Sedgwick County Juvenile Detention Facility, Wichita, Kansas, by Richard Ross. “Nobody comes to visit me here. Nobody. I have been here for eight months. My mom is being charged with aggravated prostitution. She had me have sex for money and give her the money. The money was for drugs and men. I was always trying to prove something to her…prove that I was worth something. Mom left me when I was four weeks old — abandoned me. There are no charges against me. I’m here because I am a material witness and I ran away a lot. There is a case against my pimp. He was my care worker when I was in a group home. They are scared I am going to run away and they need me for court. I love my mom more than anybody in the world. I was raised to believe you don’t walk away from a person so I try to fix her. When I was 12 my mom was charged with child endangerment. I’ve been in and out of foster homes. They put me in there when they went to my house and found no running water, no electricity. I ran away so much that they moved me from temporary to permanent JJA custody. I’m refusing all my visits because I am tired of being lied to.” — B.B., age 17.

Richard Ross’ works in the Try Youth As Youth exhibition at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

The walls of David Weinberg are not the end point of these works’ journey. An exhibition is not a triumph it is a call to action. The work begins now.

Programming during the exhibition — phone-ins to prison, discussions with ACLU lawyers and experts in the field, conversations with formerly incarcerated youth — will all direct us the right way. The gallery space works best when it sutures artists’ creative processes into a larger process that we can shape as socially informed citizens. Our process of building healthy society.

“Kids need us,” says Liss. “They need our time, they need our involvement, and they need our investment. If you own an automotive shop, open it up to kids and the community. It does take a community.”

There are a host of wonderful arts communities doing work, here in Chicago, around criminal justice reform and social equity — Project NIA, 96 Acres, AREA, Prison + Neighborhood Art Project, Lucky Pierre and Temporary Services to name a few.

The arts can trail-blaze the conversation we need to be having. Photography and film are the ammunition with which we arm our reform arguments. First we see, then we do. If art is not speaking truth to power, then really, what are we doing here?

–

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

–

David Weinberg Photography is at 300 W. Superior Street, Suite 203, Chicago, IL 60654. Open Mon-Sat 10am-5pm. Telephone: 312 529 5090.

Try Youth As Youth is on show until May 9th, 2015.

–

Text © Pete Brook / David Weinberg Photography.

Images: Courtesy of artists / David Weinberg Photography.

© Richard Ross

I never thought I’d see a trans prison guard. I didn’t think transgender persons worked in the corrections industry and — given the culture of prisons — I did not expect that a trans person would ever want to.

However, she exists and her name is Mandi Camille Hauwert.

The Marshall Project continues to uncover surprising and new angles on this nation’s prisons. Their profile of Hauwert Call Me Mandi: The Life of a Transgender Corrections Officer is no exception. It is a story with which Richard Ross, a well-traveled photographer of prisons, approached them. Alongside the photographs are Ross’ own words.

Hauwert began work at San Quentin as a male, but transitioned in the job and has been taking hormones for 3 years. She faces hostility from fellow staff.

It’s worth noting how dangerous prison systems are to transgender folk. A few weeks back, I attended Bringing To Light a conference in San Francisco, at which I learnt the routine brutalisation of LGBQIT persons at the hands of the prison system — threats of rape, the use of solitary “for protection” and all its associated deprivations, the denial of prescribed hormones, and many other daily humiliations.

Janetta Johnson spoke about surviving a 3-year federal sentence in a men’s prison. She and her colleagues at the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP) now help trans folk deal with trauma and reentry following release.

Unwittingly and without buy-in, transgender prisoners swiftly expose the oppressive logic and total inflexibility of the prison industrial complex. Follow TGIJP‘s work and that of the other organisations that presented at Bringing To Light. Their work often goes unrecognised in the larger fight for reforms and abolition, but it precisely the prisons’ adherence to patriarchy and outdated constructs of gender that establishes the tension and abuses.

Ross’ Call Me Mandi: The Life of a Transgender Corrections Officer is a brief but illuminating feature. Read it.

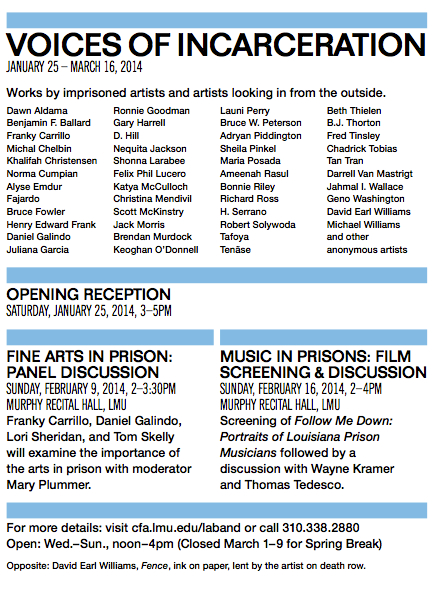

I’m not the only one putting up a show (Prison Obscura) of imagery made in and about prisons. The Laband Gallery at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles opens its Voices Of Incarceration exhibition on Saturday 25th January.

It’s an interesting line up of artists that includes artists who are imprisoned and individuals on the outside who are making art about prisons. Laband says:

“Both groups bring to light the emotional costs and injustices of the Prison Industrial Complex. Voices of Incarceration also explores the rehabilitative arts programs in California prisons and the expression of the imprisoned artists’ strength and individuality through the creative process.”

KPCC, the Los Angeles NPR-affiliate has done a couple of programs recently about the small but important attempts to reintroudce arts education into California prisons:

Efforts Emerging to Bring Arts Back to California Prisons

If you’re in L.A., go check it out. It’s open until the 16th March. One last note — it’s great to see in the mix Prison Photography favourites Alyse Emdur, Richard Ross, Michal Chelbin and Sheila Pinkel.

Photo: “Me & Myself” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

ONO ŠTO SE VIDI A NE ČUJE

If you happen to be in Belgrade, Serbia over the next couple of weeks, I encourage you to head to the Kulturni Centar Beograda (KCB) and see Seen But Not Heard, an exhibition I’ve curated of photographs from American juvenile detention facilities. The show features photographs made by incarcerated youth in photography workshops coordinated by Steve Davis in Washington State and by As220 Youth in Rhode Island, as well as well known photographers Steve Liss, Ara Oshagan, Joseph Rodriguez and Richard Ross.

The invite to put together Seen But Not Heard — which is my first international solo curating gig — was kindly extended by Belgrade Raw, an impressive photo-collective who have operated as guest exhibition coordinators at the KCB’s Artget Gallery throughout 2013. Belgrade Raw called it’s year long program Raw Season. and it was 10 exhibitions strong, including Blake Andrews, Donald Weber and others. Here’s Belgrade Raw’s announcement for Seen But Not Heard.

I’ll update the blog next week with installation shots and a loooong list of acknowledgements (the hospitality, skills and hard work of everyone here has been so overwhelming.)

Beneath, is a long essay I wrote for Seen But Not Heard . Beneath that is a selection from the 200+ works in the exhibition. Beneath the works are the details of the photographer and/or program who made them.

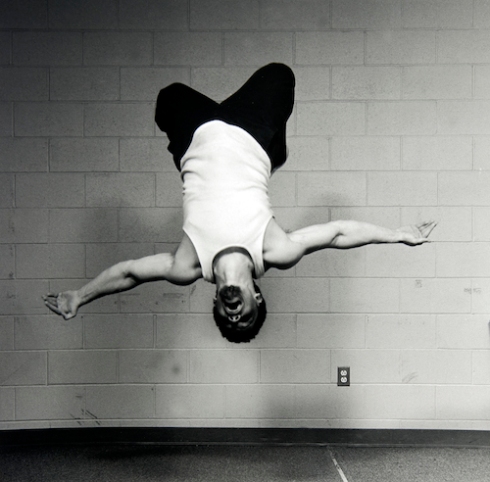

Photo: “Flip” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

ESSAY

USING PHOTOGRAPHY TO COMMUNICATE NOT CONTROL

“Ten thousand pulpits and ten thousand presses are saying the good word for me all the time … Then that trivial little Kodak, that a child can carry in his pocket, gets up, uttering never a word, and knocks them dumb.”

– Mark Twain, writing satirically in the voice of King Leopold in condemnation of the Belgian’s brutal rule over the Congo Free State. King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1905).

The United States of America is addicted to incarceration. In the course of a year, 13.5 million Americans cycle through the country’s 5,000+ prisons and jails. On any given day, 2.2 million American’s are locked up — 60,500 of whom are children in juvenile correctional facilities or residential programs. The United States imprisons children at more than six times the rate of any other developed nation. With an average cost of $80,000/year to lock up a child under the age of 18, the United States spends more than $5 billion annually on youth detention.

What do we know of these spaces behind locked doors? What do we see of juvenile prisons? The short answer is, not a lot. However, photographs can provide some information — provided we approach them with caution and an informed eye.

Seen But Not Heard features the work of five well-known American photographers who have taken their cameras inside. Crucially, the exhibition also includes photographs made by incarcerated children on cameras delivered to them by arts educators and by staff of social justice organizations. Many of the children’s photographs are being exhibited for the first time.

Cameras are used by prison administrations to maintain security and enforce order, so when a camera is operated by a visiting photographer — and especially by a prisoner — a shift in the power relations occurs. All the images in Seen But Not Heard prompt urgent questions about what it means to be able document and what it means to be prohibited from documenting. What difference is there between being the maker of an image compared to being the subject of an image? What happens if you put kids behind the camera instead of in front of it? What stories do children tell that adults cannot? Can a camera can be a tool for artistic expression instead of an apparatus of control?

EXPRESSION

“Light Paintings” made by students of the Rhode Island Training School (RITS) prove a camera is essential to the artist’s toolkit. The anonymous RITS students’ images conjure angelic limbs and alter-egos from the dark. The images contain the frustration of incarceration; the longing of a (new) time; the aspirations of youth; the childishness of comic drawing. The photography outreach program taught by AS220, a community arts group of long-standing in Rhode Island, is an extension of workshops taught to teens in the free-world. In fact, children have graduated out of RITS and into the many studio arts programs offered by AS220 Youth in the town and neighborhoods of Providence, RI. An adult would or could never make these images; it is a privilege for us to share in them.

The workshops that Steve Davis coordinated in four youth detention centers in Washington State provide us a window into the incarcerated children’s lives. For legal reasons, at Remann Hall, no images could identify the girls and so Davis made use of pinhole cameras with long exposures. The girls treated the opportunity as one for performance enacting torment, official restraint procedures and bored isolation. The blurry images are eerie and evocative; as if the girls are capturing the moments in which they are disappearing from society’s view.

By contrast, the boys’ photographs are very much embedded in reality; they carried cameras outside of structured class time with instructions to make general images and construct photographs along a weekly theme. The boys had one another as immediate audience. We see unfiltered views of their activities, cells, day rooms, programs and priorities; we see costume, computer games, machismo posturing, childlike play and even boring moments. Accidentally they collectively constructed a visual narrative in which motifs such as t-shirts, playing cards and institutional furniture recur. The photographs would be monotonous were it not for the splashed of life the children provide — perfectly communicating why and how humans kept in boxes is not the natural order, nor the ideal circumstance.

MOTIVATIONS

The photographers in Seen But Not Heard all had different motivations for going inside. After the experience, they all had the same attitudes.

Without exception, the photographers’ experiences had them wide-eyed, sometimes angry, usually frustrated and certainly more conscious of the politics of incarceration. Consequently, they feel a responsibility to share their images and to describe youth prisons to many audiences.

Steve Liss had watched the children of a Texas juvenile prisons perform a choreographed marching routine for then Texas Governor G.W. Bush. After the ridiculous spectacle, the ridiculous Bush gave a ridiculous moral instruction to stay out of trouble. Liss was furious at the patronizing tone of the event and particularly Bush. As a press photographer, Liss had parachuted in and out of that prison as quick as his subject Bush did. He vowed that if Bush ever made it to be President, he’d return to Texas to photograph the children’s lives. Bush would never see those children, but perhaps the world should. It is alarming how often we see very young and tiny children subject to shackles and apparatus designed for dangerous 200+ lb. men. It’s as if the system is blind to the physicality of its young prisoners. That being the case, how can we presume they understand or provide for the more complex psychology of these children?

Joseph Rodriguez was locked up as a young man. He also experienced homelessness, for a time, and was addicted to drugs. He was sent to the infamous Riker’s Island prison in New York twice — first, for a minor charge related to his anti-war protest activity; second, for burglary. His mother could not afford the $500. He spent 3 months locked up awaiting his court date. Post-release, Rodriguez found photography and it gave him a means to process and describe the world. Having seen the inside, Rodriguez empathizes with children who are going through any prison system. More than 20 years after his incarceration, Rodriguez felt it a duty to use his storytelling skills to tell the stories of incarcerated children. In 1999, he photographed inside the San Francisco and Santa Clara Counties juvenile detention centers and followed children through the cells, courtrooms and counseling of the criminal justice system.

Ara Oshagan’s opportunity to photograph at the Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall (the largest juvenile prison in America) was pure happenstance. He met with Leslie Neale a documentary filmmaker for lunch on a Monday. Neale was filming inside the juvenile hall and needed a photographer to shoot b-roll. Oshagan was inside on the Tuesday. He was so moved by the experience that he applied for clearance to return on his own. He followed six youngsters as they progressed through their cases and, in some cases, into California’s adult prison system. Oshagan never felt like his photographs were enough to describe the emotions of the children and so he asked each of them to write poems and presents text and image as diptych. Random circumstance, fine slices of luck, peer pressure and other people’s decisions factor far more heavily in children’s lives than in adults’ lives. Throughout, Oshagan was constantly reminded how his subjects were very much like his own children.

Late in his career and having financial security through a Guggenheim fellowship and teaching sabbatical, Richard Ross turned his lens upon juvenile detention. Ross wanted to give advocates, legislators, educators the visual evidence on which to base discussion and policy. He provides his images for free to individuals and organizations doing work for the betterment of children’s lives.

Repeatedly, Ross met children who were themselves victims; frighteningly often he heard stories of psychological, physical and sexual abuse, homelessness, suicide attempts, addiction and illiteracy. Many kids locked up are from poor communities and a disproportionate number of youths detained are boys and girls of color. Ross observed some really positive interventions made by institutions (regular meals, counseling, positive male role models to name a few) but he saw the use of incarceration not as last resort but as routine.

WHY SHOULD WE CARE?

Unsurprisingly, many have lost faith in the juvenile prison system. Recent scandals have exposed systematic abuses.

In Pennsylvania, two judges accepted millions of dollars in kickbacks from a private prison company to sentence children to custody; in Texas, an inquiry uncovered over 1,000 cases of sexual assault by staff in the state’s juvenile justice system; in New York, on Riker’s Island it has been alleged that young gangs (referred to as “teams”) organized within the jail itself, and controlled and enforced the juvenile wings while the authorities turned a blind eye. The rivalries resulted in fights, stabbings and in one case death. The New York City Department of Corrections denies the allegations, but interestingly it was NYDOC employees that exposed the violence by leaking internal photographs to the Village Voice newspaper.

Nationally, the private company Youth Services International (YSI) inexplicably continues to operate despite being cited for ‘offenses ranging from condoning abuse of inmates to plying politicians with undisclosed gifts while seeking to secure state contracts’ by the Department of Justice and also New York, Florida, Maryland, Nevada and Texas.

Not only is being locked up ineffective as a deterrent in youths who have not reached full cognitive development and don’t understand the consequences of their actions, it can actually make a criminal out of a potentially law-abiding kid. Dr. Barry Krisberg, director of research at the Berkeley School of Law’s Institute on Law & Social Policy, says, “Young people [when detained] often get mixed in with those incarcerated on more serious offenses. Violence and victimization is common in juvenile facilities and it is known that exposure to such an environment accelerates a young person toward criminal behaviors.”

THE FUTURE

Given the lessons from the failed practices of incarcerating more and more children, States are adopting more progressive policies. Certainly, authorities are turning away from punishing acts such as truancy and delinquency with detention; acts that are not criminal for an adult but have in the past siphoned youths into the court system. But more than that, incarceration for youth is widely considered a last resort.

States that reduced juvenile confinement rates the most between 1997 and 2007 had the greatest declines in juvenile arrested for violent crimes. It’s proof that incarceration doesn’t solve crime. And, it might suggest incarceration damages communities. Following repeated abuse scandals in the California Youth Authority (CYA) facilities in the 90s, California carried forth the largest program of decarceration in U.S. history. Reducing its total number of youth prisons from 11 to 3 and slashing the CYA population by nearly 90%, California simultaneously witnessed a precipitous drop in violent crime committed by under-18s.

The U.S. still has a long way to go if it is to reverse decades of over-reliance on incarceration, but as the recent Supreme Court ruling banning Life Without Parole sentences for children suggests, it seems Americans hold less punitive attitudes when it comes to youth’s transgressions, as compared to the apathetic attitudes to adult prisoners.

We need to expect and applaud photography that depicts imprisoned children as they are — as citizens-in-the-making, as humans with as complex emotional needs as any of us, as not lost causes, as victims as much as they may have been victimizers, as our future, as individuals society must look to help and reintegrate and not discard. Photography can help us appreciate the complexity of the issues at hand. Used responsibly, it can bring us closer.

Photo: “Cash Rules Everything Around Me” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

Photo: “Icarus” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

AS220

AS220 Youth is a free arts education program for young people ages 14-21, with a special focus on those in the care and custody of the state. AS220 Youth provides free studio-based classes in virtually all media including photography. Staff including photography coordinator Scott Lapham and photography instructor Miguel Rosario (who I met when I visited in 2011) help students build a portfolio with help from a staff advisor. AS220 Youth maintains long-term, supportive relationships with youth transitioning out of RITS and the Department of Children, Youth and Their Families (DCYF) care, and offers mentoring, transitional jobs, and financial support. AS220 Youth works to connect youth with professional opportunities in the arts — through exhibitions at the AS220 Gallery and others; through publication in the AS220 quarterly literary magazine called ‘The Hidden Truth’; and through securing photo-assistant jobs on commercial photo shoots for students.

Photo: Steve Liss. Prisoners, ages 10-16, wait in line to march back to their cells in the exercise yard at the Webb County Juvenile Detention facility.

Photo: Steve Liss. 10-year-old Alejandro has his mug shot taken at Webb County Juvenile Detention following his arrest for marijuana possession. Every day the inmates get smaller, and more confused about what brought them here. Psychiatrists say children do not react to punishment in the same way as adults. They learn more about becoming criminals than they do about becoming citizens. And one night of loneliness can be enough to prove their suspicion that nobody cares.

STEVE LISS

Steve Liss photographed in Texas 2001-2004. His book No Place For Children: Voices from Juvenile Detention (University of Texas Press, 2005) won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award in 2006.

Steve Liss worked as a Time Magazine photographer for 25 years, assigned to stories of social significance involving ordinary people. Forty-three of his photographs appeared on the cover of Time Magazine. For his work on juvenile justice, Liss was awarded a Soros Justice Media Fellowship (2004) for my work on domestic poverty he was awarded an Alicia Patterson Fellowship (2005). Recently, Liss received the Pictures of the Year International (PoYI) ‘World Understanding Award.’ Liss has taught graduate photojournalism at Columbia College, Chicago and Northwestern University.

Photo: Ara Oshagan, from the series ‘A Poor Imitation Of Death’

Photo: Ara Oshagan, from the series ‘A Poor Imitation Of Death’

ARA OSHAGAN

Ara Oshagan photographed inside the Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall and the California prison system. Oshagan’s book of this work A Poor Imitation of Death is to be published next year (Umbrage Books, 2014). Oshagan is twice a recipient of a California Council on the Humanities Major Grant for his documentary work on diaspora groups in Los Angeles.

Interested in the themes of identity, community and bearing witness, much of Ara Oshagan’s work focuses on the oral histories of survivors of the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Since 1995, Oshagan has been creating work for iwitness in collaboration with Levon Parian and the Genocide Project. Father Land, a book project made with his father, well-known author, Vahe Oshagan was published in 2010 by powerHouse books.

Photo: Steve Davis. ‘Tiny, Green Hill, 2000’

Photo: Anonymous student at Green Hill School. Photograph made in response to the prompt “Vulnerability” as part of photography workshop led by Steve Davis.

Photo: Anonymous student at Green Hill School. Discussing photographs made during workshop led by Steve Davis.

STEVE DAVIS

Steve Davis coordinated photography workshops in four facilities in Washington State (Maple Lane, Green Hill, Remann Hall and Oakridge) between 1997 and 2005. Simultaneously, Davis made portraits and photographs for his own series Captured Youth.

Davis is a documentary portrait and landscape photographer based in the Pacific Northwest. His work has appeared in Harper’s, the New York Times Magazine, Russian Esquire, and is in many collections, including the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, the Seattle Art Museum, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and the George Eastman House. He is a former 1st place recipient of the Santa Fe CENTER Project Competition, and two time winner of Washington Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowships. Davis is the Coordinator of Photography, Media Curator and adjunct faculty member of The Evergreen State College, Olympia, WA. Davis is represented by the James Harris Gallery, Seattle.

Photo: Joseph Rodriguez, from the series ‘Juvenile’

Photo: Joseph Rodriguez, from the series ‘Juvenile’

JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ

Joseph Rodriguez photographed in the San Francisco County Jails 2001-2004. The work is collected in his book Juvenile (PowerHouse Books, 2004)

Joseph Rodriguez is a documentary photographer from Brooklyn, New York. He studied photography in the School of Visual Arts and in the Photojournalism and Documentary Photography Program at the International Center of Photography in New York City. Rodriguez’s work had been exhibited at Galleri Kontrast, Stockholm, Sweden; The African American Museum, Philadelphia, PA; The Fototeca, Havana, Cuba; Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, Birmingham, Alabama, Open Society Institute’s Moving Walls, New York; Frieda and Roy Furman Gallery at the Walter Reade Theater at the Lincoln Center; and the Kari Kenneti Gallery Helsinki, Finland. In 2001 the Juvenile Justice website, featuring Joseph Rodriguez’s photographs, launched in partnership with the Human Rights Watch International Film Festival High School Pilot Program. He teaches at New York University, the International Center of Photography, New York. Rodriguez is the past recipient if Alicia Patterson Journalism Fellowship in 1993 photographing communities in East Los Angeles.

Photo: Photo: Richard Ross. Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall. Downey, California.

RICHARD ROSS

Richard Ross is a photographer and professor of art at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Juvenile-In-Justice (2006-ongoing) “turns a lens on the placement and treatment of American juveniles housed by law in facilities that treat, confine, punish, assist and, occasionally, harm them,” says Ross.

A book Juvenile in Justice (self-published, 2012) and traveling exhibition continue to circulate the work. Ross collaborates with juvenile justice stakeholders and uses the images as catalysts for change. For Juvenile-In-Justice, Richard Ross photographed in over 40 U.S. states in 350 facilities, met and interviewed approximately 1,000 children. Juvenile-In-Justice published on CBS News, WIRED, NPR, PBS Newshour, ProPublica, and Harper’s Magazine, for which it was awarded the 2012 ASME Award for Best News and Documentary Photography.