You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Steve Davis’ tag.

Ryan Richardson of Evergreen State College put together this lil’ promo video of Prison Obscura.

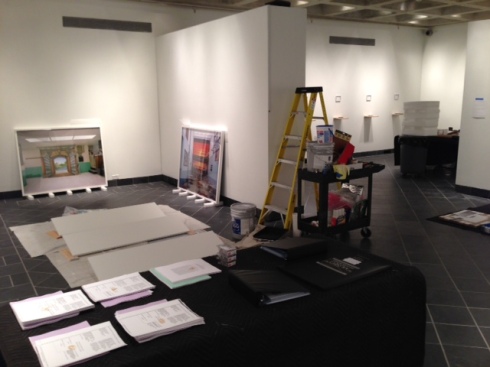

Install shots here. The larger Kept Out/Kept In program at Evergreen.

EVERGREEN OPENING NIGHT, THURS 14TH JANUARY

Prison Obscura opened at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington last Thursday. It is on show until March 2nd.

Ryan Richardson, manager of the PhotoLab at the college, made these images. They were originally shared in this post by Evergreen.

The Evergreen print shop did a stellar job with the decal for the front window of the Evergreen Gallery.

(From left to back) Kristen S. Wilkins, Steve Davis, Mark Strandquist, Robert Gumpert and photos from the landmark classaction lawsuit Brown v Plata.

One fo the opening reception attendees. Thanks to all those who came out.

Robert Gumpert‘s Take A Picture, Tell A Story in the back of the gallery.

Paul Rucker‘s Proliferation shown at a size we’ve never dared before with Prison Obscura. It was right next to the gallery entrance and visible through the windows to the world outside.

Evergreen President George Bridges (above, right) is a sociologist by training and has written extensively about crime, control and race in America. As an undergrad he interviewed prisoners in Monroe Correctional Complex, just outside Seattle. Bridges felt the strong impact of Robert Gumpert‘s portraits and interviews, he told me.

Gallery goers view the audio-slideshow of Gumpert’s interviews surrounded by 30 of his portraits from the San Francisco County jail system.

Evergreen Gallery director Ann Friedman and I. Ann and her student staff were phenomenal in their design, PR, audio/visual set-up and all other things. I’d like to thank Ruby, Cambria, Carson, Kelvin and the handful of others whose names escape me but they know who they are. Huge thank you.

UPDATED PRISON OBSCURA WEBSITE

The Prison Obscura website, maintained by the commissioners of the show Haverford College has been updated with installation shots from all venues thus far.

“If a book can have a trailer, I guess this is sort of that,” wrote Steve Davis in his email this morning.

Me Steve have a long history* but that in no way discredits what I am about to say. Whether I am biased or not (I am) this video absolute nails it. Why? The process of image-making is often messy. It get messier the more people are involved. Making photographs inside a prison — for Steve and his students — involves local authorities, management and staff. Everyone thinks they have a say or a role. If everyone is a photographer, then everyone is a photo-critic, or worse, everyone is the Photo Police.

Steve saw nice things and he saw absolutely devastating things. He met kids raised to be racists and they were very personable. He encountered kids stuck in the system and devolving to the oppressed and hardened personalities required for survival. He met staff who were moving heaven and hell to give these troubled kids the best shot at the rest of their lives, and he met adults who had already written them off and goaded the kids.

As Steve says, layers of contradictions and complex challenges exist in juvenile detention facilities. These images will not give you any easy answers; they will probably throw up more questions.

This is the best, quickest and truest introduction to Steve’s series Captured Youth that currently exists. If you like what he says an dyou like the images then pre-order the book of this work Unfinished at Minor Matters Books.

*Steve Davis was my first ever interview on Prison Photography. That happened because he was geographically the closest when I started the site. He didn’t have to say yes to the interview but he did. I must have done something right because a year later he invited me to his class to give a lecture. Steve Davis’ student were the first college students I ever presented material to. Years ago, when I was going through a really hard break-up and needed to get out of town, I headed down I5 and crashed on Steve’s couch for a couple of nights. Photographs made by incarcerated boys and girls who were students in his workshops feature in Prison Obscura. Next year, Prison Obscura will be shown at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. Steve is the coordinator of the photography program at Evergreen and introduced the show to the gallery’s curator. Steve is a friend.

10, 11, 12, 13 & 14. © Steve Davis.

TRY YOUTH AS YOUTH

Currently on show at David Weinberg Photography in Chicago is Try Youth As Youth (Feb 13th — May 9th), an exhibition of photographs and video that bear witness to children locked in American prisons. As the title would suggest, the exhibition has a stated political position — that no person under the aged of 18 should be tried as an adult in a U.S. court of law.

In the summer of 2014, selling works ceased to be David Weinberg Photography’s primary function. The gallery formally changed its mission and committed to shedding light on social justice.

Try Youth As Youth, curated by Meg Noe, was conceived of and put together in partnership with the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. Here’s art in a gallery not only reflecting society back at itself, but trying to shift its debate.

The issue is urgent. In the catalogue essay Using Science and Art to Reclaim Childhood in the Justice System, Diane Geraghty Professor of Law at Loyola University, Chicago notes:

Every state continues to permit youth under the age of 18 to be transferred to adult court for trial and sentencing. As a result, approximately 200,000 children annually are legally stripped of their childhood and assumed to be fully functional adults in the criminal justice system.

This has not always been the case in the U.S. It is only changes to law in the past few decades that have resulted in children facing abnormally long custodial sentences, Life Without Parole sentences and even (in some states) the death penalty. In the face of such dark forces, what else is art doing if it is not speaking truth to power and challenging systems that undermine democracy and our social contract?

Noe invited me to write some words for the Try Youth As Youth catalogue. Given Weinberg’s enlightened modus operandi, I was eager to contribute. Here, republished in full is that essay. It’s populated with installation shots, photographs by Steve Davis, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, and video-stills by Tirtza Even.

–

Scroll down for essay.

–

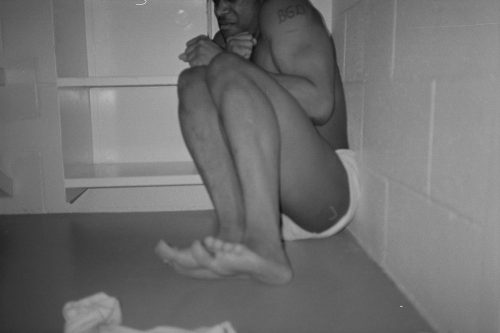

Image: Steve Liss. A young boy held and handcuffed in a juvenile detention facility, Laredo, Texas.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Image: Steve Liss. Paperwork for one boy awaiting a court appearance. How many of our young “criminals” are really children in distress? Three-quarters of children detained in the United States are being held for nonviolent offenses. And for many young people today, family relationships that once nurtured a smooth process of socialization are frequently tenuous and sometimes non-existent.

–

Try Youth As Youth Catalogue Essay

–

WHAT AM I DOING HERE?

–

Isolated in a cell, a child might wonder, “What am I doing here?” It is an immediate, obvious and crucial question and, yet, satisfactory answers are hard to come by. The causes of America’s perverse addiction to incarceration are complex. Let’s just say, for now, that the inequities, poverty, fears and class divisions that give rise to America’s thirst for imprisonment have existed in society longer than any child has. And, let’s just say, for now, that the complex web of factors contributing to a child’s imprisonment are larger than most children could be expected to understand on a first go around.

As understandable as it might be children in crisis to ask “What am I doing here?” it should not be expected. Instead, it is we, as adults, who should be expected to face the question. We should rephrase it and ask it of ourselves, and of society. What are WE doing here? What are we doing as voters in a society that locks up an estimated 65,000 children on any given night? In the face of decades of gross criminal justice policy and practice, what are we doing here, within these gallery walls, looking at pictures?

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility, Albany, Oregon, by Richard Ross. “I’m from Portland. I’ve only been here 17 days. I’m in isolation. I’ve been in ICU for four days. I get out in one more day. During the day you’re not allowed to lay down. If they see you laying down, they take away your mattress. I’m in isolation ‘cause I got in a fight. I hit the staff while they were trying to break it up. They think I’m intimidating. I can’t go out into the day room; I have to stay in the cell. They release me for a shower. I’ve been here three times. I have a daughter, so I’m stressed. She’s six months old. At 12 I was caught stealing at Wal-Mart with my brother and sister. My sister ran away from home with a white dude. She was smoking weed, alcohol. When my sister left I was sort of alone…then my mother left with a new boyfriend, so my aunt had custody. She’s 34. My aunt smoked weed, snorts powder, does pills, lots of prescription stuff. I got sexual with a five-year-older boy, so I started running away. So I was basically grown when I was about 14. But I wasn’t doing meth. Then I stopped going to school and dropped out after 8th grade. Then I was in a parenting program for young mothers…then I left that, so they said I was endangering my baby. The people in the program were scared of me. I don’t know what to think. I was selling meth, crack, and powder when I was 15. I was Measure 11. I was with some other girls — they blamed the crime on me, and I took the charges because I was the youngest. They beat up this girl and stole from her, but I didn’t do it. But they charged me with assault and robbery too. This was my first heavy charge.” — K.Y., age 19.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

I have spent a good portion of the past six-and-a-half years trying to figure out just what it is that images of prisons and prisoners actually do. Who is their audience and what are their effects? If I thought answers were always to be couched in the language of social justice I was soon put right by Steve Davis during an interview in the autumn of 2008.

“People respond to these portraits for their own reasons,” said Davis. “A lot of the reasons have nothing to do with prisons or justice. Some people like pictures of handsome young boys — they like to see beautiful people, or vulnerable people, whatever. That started to blow my mind after a while.”

My interview with Davis was the first ever for the ongoing Prison Photography project. It blew my mind too, but in many ways it also prepared me for the contested visual territory within which sites of incarceration exist and into which I had embarked. Davis’ honesty prepared me to face uncomfortable truths and perversions of truth. It readied me for the skeevy power imbalances I’d observe time and time again in our criminal justice system.

The children in Try Youth As Youth may be, for the most part, invisible to society but they are not far away. “I was just acknowledging that this juvenile prison is 20 miles from my home,” says Davis of his earliest motivations. If you reside in an urban area, it is likely you live as near to a juvenile prison, too. Or closer.

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Prisoners, and surely child prisoners, make up one of society’s most vulnerable groups. Isn’t it strange then that rarely are they presented as such? Often depictions of prisoners serve to condemn them, but not here, in Try Youth As Youth.

As we celebrate the committed works of Steve Davis, Tirtza Even, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, we should bear in mind that other types of prison imagery are less sympathetic and that other viewers’ motives are not wed to the politics of social justice. A picture might be worth a thousand words, but it’s a different thousand for everyone. We must be willing to fight and press the issue and advocate for child prisoners. Our mainstream media dominated by cliche, our news-cycles dominated by mugshots and the politics of fear, and our gallery-systems with a mandate to make profits will not always serve us. They may even do damage.

Image: Steve Davis. A girl incarcerated in Remann Hall, near Tacoma, Washington State.

Given that the works of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross circulate in a free-world that most of their subjects do not, it is all our responsibility to handle, contextualize and talk about these photographs and films in a way that serves the child subjects most. It is our responsibility to talk about economic inequality and about the have and have-nots.

“No child asks to be born into a neighborhood where you can get a gun as easily as a popsicle at the convenience store or giving up drugs means losing every one of your friends,” said Steve Liss “They were there [in jail] because there was no love, there was no nourishing, there was anger in startling doses, and there was poverty. Tremendous poverty.”

Image: Steve Liss. Alone and lonely, ten-year-old Christian, accused of ‘family violence’ as a result of a fight with an abusive older brother, sits in his cell.Every day the inmates get smaller, and more confused about what brought them here. Psychiatrists say children do not react to punishment in the same way as adults. They learn more about becoming criminals than they do about becoming citizens. And one night of loneliness can be enough to prove their suspicion that nobody cares.

Davis, Even, Liss and Ross understand the burden is upon us as a society to explain our widespread use of sophisticated and brutal prisons more than it is for any individual child to explain him or herself. The image of an incarcerated child is an image not of their failings, but of ours. We must do better — by providing quality pre and post-natal care for mothers and babies, nutritious food, livable wages for parents, and support and safety in the home and on the streets. Most often, it is a series of failures in the provision of these most basic needs that leads a child to prison.

“Poverty would be solved in two generations. It would require an enormous change in our priorities. Look at how we elevate the role of a stockbroker and denigrate the role of a school teacher or a parent, those who are responsible for raising the next generation of Americans,” says Liss.

(Top to Bottom) Installation shot; video still; and drawings from Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez’s Natural Life, 2014.

Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez. Natural Life, 2014. Cast concrete (segment of installation). A cast of five sets of the standard issue bedding (a pillow, a bedroll) given to prisoners upon their arrival to the facility, are arranged on raw-steel pedestals in the area leading to the video projection. The sets, scaled down to kid size and made of a stack of crumbling and thin sheets of material resembling deposits of rock, are cast in concrete. Individually marked with the date of birth and the date of arrest of each of the five prisoners featured in the documentary, they thus delineate the brief time the inmates spent in the free world.

Each of the artists in Try Youth As Youth have seen incredible deprivations inside facilities that do not — cannot — serve the needs of all the children they house. Ross speaks of a child who has never had a bedtime. A social worker once told Davis of one child in the system who had never seen or held a printed photograph.

Documenting these sites is not easy and brings with it huge responsibility. Tirtza Even has grappled with the weight of her work “and how much is expected from them is a little heavy.” In some cases, these artists are the outside voice for children. Liss acknowledges that expectations more often than not outweigh the actual effects their work can have.

“People ask how do you get close to kids in a facility like that. That isn’t the problem. The problem is how do you set up enough artificial barriers so you don’t get too close. So you’re not just one more adult walking out on them in the final analysis,” he says. “I, at least, convinced myself into thinking it was therapeutic for the kids. At least someone was listening to them.”

So far, the efforts of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross have been recognized by those in power. Liss’ work has been used to lobby for psych care and an adolescent treatment unit in Laredo, Texas. Ross’ work was used in a Senate subcommittee meeting that legislated at the federal level against detained pre-adjudicated juveniles with youth convicted of committed hard crimes.

“That’s a great thing for me to know that my work is being used for advocacy rather than the masturbatory art world that I grew up in,” says Ross.

Sedgwick County Juvenile Detention Facility, Wichita, Kansas, by Richard Ross. “Nobody comes to visit me here. Nobody. I have been here for eight months. My mom is being charged with aggravated prostitution. She had me have sex for money and give her the money. The money was for drugs and men. I was always trying to prove something to her…prove that I was worth something. Mom left me when I was four weeks old — abandoned me. There are no charges against me. I’m here because I am a material witness and I ran away a lot. There is a case against my pimp. He was my care worker when I was in a group home. They are scared I am going to run away and they need me for court. I love my mom more than anybody in the world. I was raised to believe you don’t walk away from a person so I try to fix her. When I was 12 my mom was charged with child endangerment. I’ve been in and out of foster homes. They put me in there when they went to my house and found no running water, no electricity. I ran away so much that they moved me from temporary to permanent JJA custody. I’m refusing all my visits because I am tired of being lied to.” — B.B., age 17.

Richard Ross’ works in the Try Youth As Youth exhibition at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

The walls of David Weinberg are not the end point of these works’ journey. An exhibition is not a triumph it is a call to action. The work begins now.

Programming during the exhibition — phone-ins to prison, discussions with ACLU lawyers and experts in the field, conversations with formerly incarcerated youth — will all direct us the right way. The gallery space works best when it sutures artists’ creative processes into a larger process that we can shape as socially informed citizens. Our process of building healthy society.

“Kids need us,” says Liss. “They need our time, they need our involvement, and they need our investment. If you own an automotive shop, open it up to kids and the community. It does take a community.”

There are a host of wonderful arts communities doing work, here in Chicago, around criminal justice reform and social equity — Project NIA, 96 Acres, AREA, Prison + Neighborhood Art Project, Lucky Pierre and Temporary Services to name a few.

The arts can trail-blaze the conversation we need to be having. Photography and film are the ammunition with which we arm our reform arguments. First we see, then we do. If art is not speaking truth to power, then really, what are we doing here?

–

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

–

David Weinberg Photography is at 300 W. Superior Street, Suite 203, Chicago, IL 60654. Open Mon-Sat 10am-5pm. Telephone: 312 529 5090.

Try Youth As Youth is on show until May 9th, 2015.

–

Text © Pete Brook / David Weinberg Photography.

Images: Courtesy of artists / David Weinberg Photography.

IS THE INTERNET BECOMING LESS SNARKY?

Portraits of incarcerated youth made by Steve Davis were published on BuzzFeed yesterday. That they are featured does not surprise me; no, it is the reasonable comments that follow that surprise me.

They internet, a space known to often bring out the worst in people has had a special place for trolls as far as images of American prison and prisoners are concerned. Often photographs themselves are bypassed in discussion in order for commenters to shortcut straight to their long held positions — by they left or right, sympathetic or not, nuanced or short-sighted, familiar or prejudiced. Prisons are a divisive issue and often people miss the point of prison photographers who, in the first instance at least, are merely trying to hold a mirror to a system. In this case, Davis holds a mirror to a nation that locks up 65,000 youth on any given night at a cost of $5billion per year.

In my own prejudice, I would’ve expected THE INTERNET + BUZZFEED + KIDS IDENTIFIED AS CRIMINALS would be an equation for vitriol. Not so.

Why would I be so pessimistic? Well, despite BuzzFeed founder Jonah Peretti’s insistence that serious, longform news can exist beside listicles — and despite recent pieces — on last meals of the executed, a trans-activist transforming a prison from within, reflections on wrongful conviction, and the shacking of women prisoners in labor — BuzzFeed content still leasn heavily on shock, innumerable pet vids, “27 things you only know if…” nonsense, and flashes of celeb flesh. The lowest denominators remain our and BuzzFeed’s bread and butter.

All that said, let’s just be thankful for this comment thread:

Some of these faces are so hard. Some are bewildered. And some are just heartbreaking. So beautiful and tragic.

Each one of these faces should never have ended up there. Their incarceration marks the failure of society to raise contributing citizens.

That would imply that society failed every person who has made bad choices. That’s simply not a generalization that pans out entirely. I don’t disagree that we have failed many of these faces as a society, just the generalization.

Look to the parents. Well, perhaps they are/were also incarcerated. Sad all around.

There needs to be a better solution to helping these kids achieve more in life. Yes punish them for their crimes but surely there is better way! Locking them up like this gives them no hope of something better! Nobody but them know the full story so why jump to saying they “deserve” it? some of these kids have been failed by family, peers, society which has resulted in this! Tragic!

I think we should look to the systems used in Scandinavian countries — humane prisons, lots of community service, a focus on rehabilitation, not punishment. …Or we could just stop monetizing the prison system, that would help.

The system makes money off of these children, and I guarantee you there is not one child in there whose parents have a little bit of money! Our prisons are filled with poor people! Justice is definitely not blind!

I can see where you’re coming from, but in my personal experience (two relatives that have been incarcerated both as youth and as adults), there are individuals who will, regardless of the number of chances given, continue to make the wrong choices. You can not force, coerce, or convince someone to act and live as you see fit. They will make choices of their own. These are individuals that do, in fact, deserve the punishments they receive. Like you said only they know the whole story, but regardless of that fact, there are some choices that incarcerated individuals have made that have impacted the lives of innocent people. Do those choices, then, not merit the fullest punishment?

I DO, however, believe there are also individuals who can be guided into a better life because they’ve only known one way. These are the individuals that CHOOSE to make themselves better, both in their own eyes and in societies eyes. They make the choice, and seek out those that can help guide them.

One summer in college, I had an internship in WA for an office of juvenile probation. I went to one of these places with one of the counselors because one of the kids was going to be getting out soon and heading home. This kid was probably 14 or 15 and I remember him sitting there crying because he didn’t want to leave. He had been in out of the system for years and I remember him telling us that no matter how bad it was there, he knew he was going to get fed and have a place to sleep. He told us that he was going to do something as soon as he got out that would send him back. It was tragic on so many levels. Everyone had just given up on this kid and he had pretty much given up on himself.

Locking up a young person in prison is always a shocking and sad thing, but what concerns me is people’s knee jerk reaction that all youth incarceration reflects society’s ultimate failure. Remember, most of you are also the same people who regularly rage against the violent and intolerable stories we read about rape and murder that we regularly see on this site. There are thousands of teenagers (perhaps some of the faces you are seeing here) who are guilty of these crimes. Are you saying that we needn’t incarcerate minors who commit violent crime? Should these individuals only be counseled then allowed to return into society? Despite the fact that several here have unilaterally declared that each of these incarnations are the wholesale fault of society’s failure?

But our prisons out not filled to the brim with people who have committed the kinda of crimes you speak of, and THAT is the failure.

I work in the teen department of my library system, and every librarian takes turns to go visit our JDC to talk to the kids there and find books for them in the collection we maintain at the facilities for them. It’s hard seeing them…especially when they’re super young (I swear a couple I’ve seen couldn’t be older than 11), or especially when you’ve helped them in your branch before. It sucks, and I just always hope that they can come around and learn from the experience and never become a repeat offender.

I have a serious problem with photographers leaving their [captioning on] photos blank when it comes to picturing at risk groups. Each has their own valuable story to tell and name. They are not just “black kids: or troubled youths or street punks etc…the categories that pop up due to the viewers own prejudices. We live in a fucked up world. Such photography should be there to give names to the victims and not participate in their being reduced to a number in the “incarceration game.”

Perhaps the Facebook-linked comment board has sophistication to remove idiot comments and promote those exhibiting most human thought?

Internet, you have my faith again.

Even the commenter that wonders about an anonymous portrait showing a youth with painted nails and foolishly labels the child as possibly “a fabulous homosexual” goes on to demonstrate a knowledge of the system that is unable to adequately care for LGBQIT youth; “In adult prisons obviously gay or transgendered individuals are usually put in solitary confinement for their own protection.” We know that is an unacceptable situation. LGBQIT prisoners are denied access to programming because prisons cannot guarantee their safety in general population.

Unfinished: Incarcerated Youth

Steve Davis is currently taking pre-orders for a book of his photographs from Washington State juvenile prisons, titled, Unfinished: Incarcerated Youth.

You can preorder with Minor Matters Books.

After stints at Haverford College, PA; Scripps, CA; and Rutgers, NJ, my first solo-curated effort Prison Obscura is all grown up and headed to New York.

It’ll be showing at Parsons The New School of Design February 5th – April 17th:

Specifically, it’s at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, located at 2 West 13th Street, New York, NY 10011.

On Thursday, February 5th at 5:45 p.m, I’ll be doing a curator’s talk. The opening reception follows 6:30–8:30 p.m. It’d be great to see you there.

Here’s the Parsons blurb:

The works in Prison Obscura vary from aerial views of prison complexes to intimate portraits of incarcerated individuals. Artist Josh Begley and musician Paul Rucker use imaging technology to depict the sheer size of the prison industrial complex, which houses 2.3 million Americans in more than 6000 prisons, jails and detention facilities at a cost of $70 billion per year; Steve Davis led workshops for incarcerated juvenile in Washington State to reveal their daily lives; Kristen S. Wilkins collaborates with female prisoners on portraits with the aim to compete against the mugshots used for both news and entertainment in mainstream media; Robert Gumpert presents a nine-year project pairing portraits and audio recordings of prisoners from San Francisco jails; Mark Strandquist uses imagery to provide a window into the histories, realities and desires of some incarcerated Americans; and Alyse Emdur illuminates moments of self-representations with collected portraits of prisoners and their families taken in prison visiting rooms as well as her own photographs of murals in situ on visiting room walls, and a mural by members of the Restorative Justice and Mural Arts Programs at the State Correctional Institution in Graterford, PA. Also, included are images presented as evidence during the landmark Brown v. Plata case, a class action lawsuit that which went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States, where it was ruled that every prisoner in the California State prison system was suffering cruel and unusual punishment due to overcrowded facilities and the failure by the state to provide adequate physical and mental healthcare.

Parsons has scheduled a grip of programming while the show is on the walls:

Mid-day discussion with curator Pete Brook and Tim Raphael, Director, The Center for Migration and the Global City, Rutgers University-Newark.

Wednesday, February 4, 12:00–1:30 p.m.

Co-hosted with the Humanities Action Lab.

These Images Won’t Tell You What You Want: Collaborative Photography and Social Justice.

Friday, February 27, 6:00 p.m.

A talk by Mark Strandquist.

Windows from Prison

Saturday, February 28

A workshop led by Mark Strandquist. More information about participation will be available on the website.

Visualizing Carceral Space

Thursday, March 12, 6:00 p.m.

A talk by Josh Begley.

Please spread the word. Here’s a bunch of images for your use.

PARTNERS

At The New School, Prison Obscura connects to Humanities Action Lab (HAL) Global Dialogues on Incarceration, an interdisciplinary hub that brings together a range of university-wide, national, and global partnerships to foster public engagement on America’s prison system.

Prison Obscura is a traveling exhibition made possible with the support of the John B. Hurford ‘60 Center for the Arts and Humanities and Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

Just a quick post to say …

It happened. Prison Obscura opened. With a fantastic turnout. Gallery was crammed for the curator’s talk and people said many nice things. I pulled my usual trick, clocking silly hours until the early hours most of last week during install. Matthew Seamus Callinan, the Associate Director of Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery and Campus Exhibitions at Haverford College did the same. I cannot thank Matthew enough for his support throughout the creation of the show. Legend. More thanks to so many people.

I haven’t any pictures of the opening because my head was spinning. There’s some on Facebook. I’m sure others have some too (send ‘em over!) but I wanted to do a quick post with some installation shots. Taken at different points during the week during install and may not reflect exactly the final layout. (Buckets and hardware not part of the show).

Prison Obscura is up until March 7th at the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College, just outside Philadelphia, PA. All you need to know about the exhibit is here.

It is with giddy, air-punching pride and mammoth-sized gratitude for those that helped me along the way that I announce the imminent opening of Prison Obscura.

This exhibition is my first solo-curating gig and reflects my thinking right now about images of and from American prisons. Prison Obscura includes works, approaches and genres that — after 5-years of looking at prison photographs — I consider most informative, responsible, challenging and useful.

Prison Obscura is on show at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery from January 24 through March 7. The CantorFitz built a remarkable Prison Obscura website to accompany the exhibition, at which you can find a lengthy 5,000-word essay as to why I have shied away from traditional documentary work and focused instead on surveillance, code, vernacular snaps, prisoner-made photographs and rarely-seen evidentiary images.

I posit that certain images can more accurately speak to political realities in America’s prison industrial complex. I also celebrate photographs that were made through processes of collaboration with prisoners and with intention to socially engage the subjects and educate audiences. I want you to wonder why you — a tax-paying, prison-funding citizen — rarely gets the chance to see inside prisons, and I want us to think about what roles existing pictures serve for those who live and work within the system.

Scroll down to learn more about the Prison Obscura artists.

Photographer Unknown. Clinical contact holding cage, Administrative Segregation Unit (ASU), C-Yard, Building 12, Mule Creek State Prison, California. August 1st, 2008. Used by law firms representing imprisoned plaintiffs in class action lawsuit against the State of California in the Plata/Coleman vs. Brown cases.

Photographer Unknown. Group holding cages, C-Yard, Building 13, Administrative Segregation Unit, Mule Creek State Prison, August 1st, 2008. Used by law firms representing imprisoned plaintiffs in class action lawsuit against the State of California in the Plata/Coleman vs. Brown cases.

Suicide watch cell, Building 6A, Facility D, Wasco State Prison, California (August 1st, 2008). This photograph document was submitted as evidence in the Brown vs. Plata class action lawsuit (Supreme Court of the United States, May 2011). Photo: Anonymous, courtesy of Rosen Bien Galvan & Grunfeld LLP.

Photographer Unknown. Reception Center Visiting / Clinician Office Space, North Kern State Prison, July, 2008. Used by law firms representing imprisoned plaintiffs in class action lawsuit against the State of California in the Plata/Coleman vs. Brown cases.

PRISON OBSCURA ARTISTS

Alyse Emdur’s collected letters and prison visiting room portraits as well as Robert Gumpert’s recorded audio stories from within the San Francisco jail system provide an opportunity to see, read, and listen to subjects in the contexts of their incarceration.

Juvenile and adult prisoners in different workshops led by Steve Davis, Mark Strandquist, and Kristen S. Wilkins perform for the camera, reflect on their past, describe their memories, and self-represent through photographs.

Prison Obscura will also feature work made in partnership with the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program. Men from Graterford Prison who are affiliated with both its own Restorative Justice Program and Mural Arts’ Restorative Justice Group are collaborating to create a mural for the exhibition.

The exhibit moves between these intimate portrayals of life within the prison system to more expansive views of legal and spatial surveillance in works like Josh Begley’s manipulated Google Maps’ API code and Paul Rucker’s animated videos, which offer a “celestial” view of the growth of the prison system.

Prison Obscura builds the case that Americans must come face to face with these images to grasp the proliferation of the U.S. prison system and to connect with those it confines.

Scroll down for media, details and events.

Mark Strandquist. Pocahontas State Park, Picture of the Dam. One Hundred and Thirty Days (top); text describing the scene written by a Virginia prisoner (bottom). From the series Some Other Places We’ve Missed.

Josh Begley Facility 237. From the series Prison Map.

50 of the 5,393 facilities imaged by Prison Map, a data art project which automatically “photographs” every locked facility in the U.S. by gleaning files from Google Maps with use of code modified from the Google API code by artist Josh Begley.

Josh Begley Facility 492 From the series Prison Map.

Photographer unknown. Incarcerated girls at Remann Hall, Tacoma, Washington, reenact restraint techniques in a pinhole camera workshop, 2002. Photo: Courtesy of Steve Davis.

Photographer unknown: Untitled, Green Hill School, Chehalis, WA. Photo: Courtesy of Steve Davis.

Photographer unknown: Steve Davis Untitled, Green Hill School, Chehalis, WA. Photo: Courtesy of Steve Davis.

David Wells, Thumb Correctional Facility, Lapeer, Michigan. From the series ‘Prison Landscapes (2005-2011).’ Photo: Courtesy of Alyse Emdur.

Alyse Emdur. Anonymous Backdrop Painted in Woodbourne Correctional Facility, New York. From the series ‘Prison Landcapes’ (2005- 2011)

Robert Gumpert. Tameika Smith, 9 July 2012, San Francisco, CA. From the series ‘Take A Picture, Tell A Story.’

Robert Gumpert. Michael Johnson, 15 August, 2009, San Francisco County Jail 5, San Bruno, CA. From the series ‘Take A Picture, Tell A Story.’

Kristen S. Wilkins. Supplication #17 (diptych). “It might be hard to find, but it’s called Trapper Peak near the Bitterroot Valley.” From the series ‘Supplication.’

Kristen S. Wilkins. Supplication #17 (diptych). “It might be hard to find, but it’s called Trapper Peak near the Bitterroot Valley.” From the series ‘Supplication.’

EVENTS

I’ll be giving a curator’s talk in the gallery on Friday, January 24, 2014, 4:30-5:30pm, followed by the opening reception 5:30–7:30pm.

Additionally, poet C.D. Wright will be on campus for a Tri-College Mellon Creative Residency in conjunction with the exhibit, and on January 31, at 12 noon in the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Wright and I will host a dialogue about Prison Obscura.

DETAILS

Prison Obscura is presented by Haverford College’s John B. Hurford ’60 Center for the Arts and Humanities with support from the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program.

Part of the John B. Hurford ’60 Center for the Arts and Humanities and located in Whitehead Campus Center, the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery is open Monday through Friday 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturdays and Sundays 12 p.m. to 5 p.m., and Wednesdays until 8 p.m.

Haverford College is located at 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA, 19041.

SPREADING THE WORD

View and download press images here. For interviews or variant images contact me. Here’s a big postcard.

For more information, please contact myself or Matthew Callinan, associate director of the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery and campus exhibitions, at (610) 896-1287 or mcallina@haverford.edu

Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery on Facebook (including installation) and Twitter.

Haverford College on Twitter.

Hurford Center for the Arts on Twitter.