You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Los Angeles’ tag.

Dale Hammock at the Amity Foundation in Los Angeles. Credit Damon Casarez for The New York Times. From the story ‘You Just Got Out Of Prison. Now What?

True to form in traditional media another impressive feature piece about the criminal justice system You Just Got Out of Prison. Now What? was released by the New York Times last week. The story is summed up perfectly in the sub-header: “Carlos and Roby are two ex-convicts with a simple mission: picking up inmates on the day they’re released from prison and guiding them through a changed world.”

Carlos and Robery help people like Dale Hammock (above) who was imprisoned for 21 years to readjust to the outside world.

It wasn’t until the mid-2000s that this looming ‘‘prisoner re-entry crisis’’ became a fixation of sociologists and policy makers, generating a torrent of research, government programs, task forces, nonprofit initiatives and conferences now known as the ‘‘re-entry movement.’’ The movement tends to focus on solving structural problems, like providing housing, job training or drug treatment, but easily loses sight of the profound disorientation of the actual people being released. Often, the psychological turbulence of those first days or weeks is so debilitating that recently incarcerated people can’t even navigate public transportation; they’re too frightened of crowds, too intimidated or mystified by the transit cards that have replaced cash and tokens.

The quality of the photography met the quality of the writing. The two pictures accompanying the piece were made by Damon Casarez.

An unfamiliar name. I looked him up. This was great assigning by NYT. Throughout Casarez’s other bodies of work is something of the uncanny. From an early project depicting the “Utopia” of the suburb he grew up in (Clearly effected, he mentions “suburb” in his bio) to a series of actors playing out cliche types who live in his neighbourhood, it seems Casarez is obsessed with the weird around him.

Or more precisely he teases the weird out.

From the unnatural order of Boomerang Kids (children that return to parents’ home after college graduation) to a series titled Dioramas of recreations of peculiar vignettes in everyday life around him, Casarez channels Jennifer Karady, Holly Andres, early Gregory Crewdson, the vulgar Jill Greenberg, and David Lynch, (and, yeah, I guess, even Hopper).

Everyone has been talking about Google’s neural network DeepDream recently saying that it might be the closest thing to what Androids dream of when they sleep or what pure (LSD-inflected) visuals look like. The world is a freaking bizarre place and it only because of inbuilt systems to filter most of it that our brains don’t get overrun.

Casarez’s work is so appealing to me because it bucks that tendency. He searches out the ill-fitting and garish surface tensions we put on, prop up and rely on daily.

It makes sense why the worlds of (predominantly) Southern California would weird him out. One day he’s photographing victims’ families of street violence, and the next the aspiring and upper classes basking in the arts-industrial complex.

As odd places, prisons do nothing if not produce odd behaviours and characters. Carlos and Roby have been out years but still fantasize about prison food. They are the sanest folks engaging with the prison issue because they see reentry from a personal and informed perspective .. and yet they sit for hours in their car under the words “Now what?” waiting for a man who’ll probably arrive. He does and their work begins.

Roby So (left) and Carlos Cervantes in Pomona, California. Damon Casarez for The New York Times. From the story ‘You Just Got Out Of Prison. Now What?

For all the quantitative research, NGO white papers, expert testimony, politicians’ best intentions, it is still the one-one-one, face-to-face, simple and small things that make the biggest difference in getting people out and keeping people out. That might sound crazy but it is not; it’s true. For example, the Prisoner Reentry Network does something as simple as send directions to prisoners pre-release so that they know how to get from the prison gate to the their hometown. Having not navigated the free world for years or decades that’s key information the rest of us take for granted.

No one has experimented so perversely with prisons as California. The unexpected details, the frank reporting and the NYT’s choice of photographer all worked well together here and described an unnatural situation and set of problems to which committed folks are trying to find solutions.

–

The city of Los Angeles has the highest population of incarcerated youth of any city on the planet. A new non-profit on the block, named New Earth, that offers programs for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated youth in the City of Angels is working with media, music, gardens and outward-bound programs to offer children skills, alternatives to gang life.

New Earth claims that their efforts have reduced rates recidivism from 80% to 5% among those in their program. Quite a statistic!

You can see the work of students here and below is New Earth’s latest press release.

From New Earth:

A Step to Ending the Youth-to-Prison Pipeline – New Earth’s Programs Reduce the LA County Youth Recidivism Rate From 80% to 5%

It is time to shed light on an unacceptable unspoken fact that lies in the belly beneath the surface of awareness in Los Angeles. As of July 2014, there are roughly 30,000 young people on probation or locked up in L.A. County, more than any other metropolitan area in the world. 95% of these youth face incarceration for nonviolent offenses. Once a young person meets such a fate, there is an 80% recidivism rate, which means 80% will end up incarcerated again. This system is broken and its rehabilitation depends upon the deployment of acute and revolutionary tactics.

New Earth, a non-profit started in 2004, is making significant strides in reducing the recidivism rate in Los Angeles. They provide mentor-based arts, educational and vocational programs to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated youth ages 13-22. These programs aim to reduce the recidivism rate by empowering these youth’s lives, and enable them to reach full potential as contributing members of our community.

It’s working.

New Earth’s programs have an incredible success rate. Once a youth starts a New Earth program while incarcerated and continues on with New Earth programs and services post release, his chance of getting re-incarcerated drops down from 80% to less than 5%. It costs taxpayers $125,000 per year to lock up one youth, however it takes a mere $3,500 to put one young person through the New Earth programs for an entire year. Youth remain free from gangs, crime and jail – they’re kept inspired, productive and ALIVE. Today, New Earth serves 2,500 young people per year in 9 out of the 18 juvenile probation camps in Los Angeles County. They work with more incarcerated youth in L.A. than any other non–governmental organization.

“Our goal is to reduce the recidivism rate in Los Angeles and keep these kids from coming back to the camps, going to prison or worse yet, becoming a statistic” explains Harry Grammer, Founder and CEO of New Earth.

The results are inspiring. One of New Earth’s foundational programs is F.L.O.W, an acronym for Fluent Love of Words, which is a writing, poetry and music program based on the California Common Core Standards of Education. Through the discovery of their unique voice, youth begin to realize their potential as artists, creators and instruments of positive societal change. These programs have the ability to prevent violence, increase social consciousness, and expand vocabularies and reading comprehension by creating safe places for creative expression. This leads to broadening of their sense of freedom and self-esteem, and recrafting of their attitudes towards authority, their peers, and their self-perception.

“New Earth has changed my life in many ways,” says Alex Pham (21) a program alumni who now works at the New Earth offices as a camera operator. “It has changed how I view the simplest things in life. The love, care, and appreciation the viewers have for the job I do is incredibly outstanding. It made me realize that we should appreciate more and be grateful for every little thing in life.”

The road to change within the historically harsh and unjust industrial prison system is one with deep rooted complexities, but New Earth’s programs are a firm step in the direction of repair and life-changing retribution.

SOCIAL

Every other month, New Earth hosts awareness mixers to share information about the problems of youth prison systems and its own contributions to combat them.

The next mixer is on Wednesday July 30th, 5:30pm-7:30pm at the Center for Arts and Educational Justice, 3131 Olympic Blvd. 2nd Floor, Santa Monica, CA 90404.

You can contact Melissa Wynne-Jones on 415-637-2965 and melissa@theconfluencegroup.com, or visit www.newearthlife.org for more info or call 310-455-2847. RSVP for the mixer at info@newearthlife.org

Coinciding with San Francisco’s annual Pride events and the 45th anniversary of the Stonewall riots in New York City, Anthony Friedkin’s seminal body of work The Gay Essay goes on show this month at the De Young Museum, in San Francisco.

The Gay Essay chronicles the gay communities of Los Angeles and San Francisco between 1969 a 1973 — an era of great strides for political activism in the gay communities in California and nationwide.

Friedkin (b.1949) has always been committed to documenting cultures in his home state of California. The Gay Essay was one of his earliest efforts; he embarked on it as a 19-year-old. Self-assigned, Friedkin went poolside, to the city streets, and into motels, bars and discos in an attempt to create the first extensive record of gay life in the Golden State.

“Friedkin found his place in an approach that retained the outward-looking spirit of reportage combined with individual discovery. As an extrovert with an avid curiosity, he developed close relationships with his subjects that enabled him to create portraits that are devoid of judgment,” says the de Young press release. “He did not aim to document gay life in Los Angeles and San Francisco slavishly, but rather to show men and women who were trying to live openly, expressing their individualities and sexualities on their own terms, and improvising ways to challenge the dominant culture.”

In 1973, the San Francisco Art Week wrote, “The Gay Essay is comparable in magnitude to Robert Frank’s The Americans. The exhibit in its entirety is amazingly strong. And for the most part the photographs are singularly beautiful in execution.”

And yet, The Gay Essay has remained known, since, primarily only to photo-boffins. Consequently, I am personally eager to see this work. It’s “footprint” is not as large as its social significance warrants. Indeed, at the time of writing, a search “Anthony Friedkin” on Google has as the first result a speculative piece I posted on Prison Photography nearly five years ago. (Who knows, perhaps Google’s search metrics might shift a little once Friedkin and The Gay Essay enjoy new press interest for this big De Young show?)

The paucity of images and information on the internet is indicative of a wider photo culture that just hasn’t had Friedkin on the radar. This dearth has been reflected in the real world too. While selections from The Gay Essay have been on public display in museums and galleries in the past, the entire scope of the series — 75 vintage prints — has never been exhibited before in one venue.

“The Gay Essay accords with our goal of bringing to light important, and sometimes neglected or overlooked, bodies of work that enrich the history and study of photography, a medium that is central to art and society today,” said Colin B. Bailey, director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

If you’re in the Bay Area at any point in the next six months, I recommend catching this exhibition.

EXHIBITION DETAILS

The Gay Essay runs June 14, 2014 – January 11, 2015, at the DeYoung Museum, Golden Gate Park, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118.

Accompanying the original full-frame black-and-white prints will be contact prints, documents and other materials from the photographer’s archive and loans from the San Francisco Public Library and the San Francisco Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society that provide valuable historical context and insight into the conception and execution of the work.

Exhibition catalogue: 144 pages, Yale University Press. Hardcover $45.

Read more at Los Angeles Times, and at DRKRM Gallery.

All images: © Anthony Friedkin

BIOGRAPHY

Anthony Friedkin started out as a photojournalist working as a stringer for Magnum photos in Los Angeles. Friedkin’s photographs are included in major Museum collections including the Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, San Francisco MoMA and The J. Paul Getty Museum. His work has been published internationally including in Rolling Stone, Newsweek and others. He lives in Santa Monica, California.

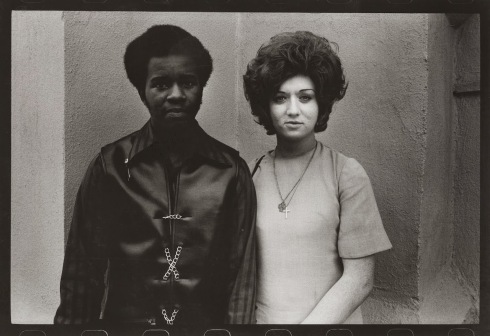

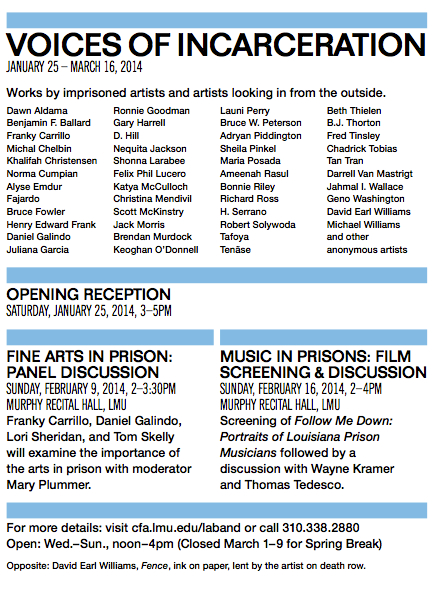

I’m not the only one putting up a show (Prison Obscura) of imagery made in and about prisons. The Laband Gallery at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles opens its Voices Of Incarceration exhibition on Saturday 25th January.

It’s an interesting line up of artists that includes artists who are imprisoned and individuals on the outside who are making art about prisons. Laband says:

“Both groups bring to light the emotional costs and injustices of the Prison Industrial Complex. Voices of Incarceration also explores the rehabilitative arts programs in California prisons and the expression of the imprisoned artists’ strength and individuality through the creative process.”

KPCC, the Los Angeles NPR-affiliate has done a couple of programs recently about the small but important attempts to reintroudce arts education into California prisons:

Efforts Emerging to Bring Arts Back to California Prisons

If you’re in L.A., go check it out. It’s open until the 16th March. One last note — it’s great to see in the mix Prison Photography favourites Alyse Emdur, Richard Ross, Michal Chelbin and Sheila Pinkel.

–

UPDATE, 05/14/2013: Harpers Books confirmed that the collection was bought by an individual at Paris Photo LA.

–

At Paris Photo: Los Angeles, this week, a collection of California prison polaroids were on display and up for sale. The asking price? $45,000.

The price-tag is remarkable, but so too is the collection’s journey from street fair obscurity to the prestigious international art fair. It is a journey that took only two years.

The seller at Paris Photo LA, Harper’s Books named the anonymous and previously unheard-of collection The Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive. Harper’s has since removed the item from its website, but you can view a cached version here. The removal of the item leads me too presume that it has sold. Whether that is the case or not, my intent here is not to speculate on the current price but on the trail of sales that landed the vernacular prison photos in a glass case for the eyes and consideration of the photo art world.

The Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive on display at Paris Photo LA in April, 2013.

FROM OBSCURITY TO COVETED FINE ART COMMODITY

In Spring 2012, I walked into Ampersand Gallery and Fine Books in NE Portland and introduced myself to owner Myles Haselhorst. Soon after hearing my interest in prison photographs, he mentioned a collection of prison polaroids from California he had recently acquired.

You guessed it. The same collection. Where did Myles acquire it and how did it get to Paris Photo LA?

“I bought the collection from a postcard dealer at the Portland Postcard Show, which at the time was in a gymnasium at the Oregon Army National Guard on NE 33rd,” says Haselhorst of the purchase in February, 2011.

As the postcard dealer trades at shows up and down the west coast, Haselhorst presumes that dealer had picked up the collection in Southern California.

Haselhorst paid a low four figure sum for the collection – which includes two photo albums and numerous loose snapshots totaling over 400 images.

“I thought the collection was both culturally and monetarily valuable,” says Haselhorst. “At the time, individual photos like these were selling on eBay for as much as $30 each, often times more. I bought them with the intention of possibly publishing a book or making an exhibition of some kind.”

Indeed, Haselhorst and I discussed sitting down with the polaroids, leafing through them, and beginning research. As I have noted before, prison polaroids are emerging online. I suspect this reflects a fraction of a fledgling market for contemporary prison snapshots. Not all dealers bother – or need to bother – scanning their sale items.

Haselhorst and I were busy with other ventures and never made the appointment to look over the material.

“In the end, I didn’t really know what I could add to the story,” says Haselhorst. “And, I didn’t want to exploit the images by publishing them.”

Another typical and lucrative way to exploit the images would have been to break up the collection and sell them as single lots through eBay or at fairs, but Haselhorst always thought more of the collection then the valuation he had estimated.

In January 2013, Haselhorst sold the collection in one lot to another Portland dealer, oddly enough, at the Printed Matter LA Art Book Fair.

“Ultimately, after sitting on them for more than two years, I decided they would be a perfect fit for the fair, not only because it was in LA, but also because the fair offers an unmatched cross section of visual printed matter. It was hard putting a price on the collection, but I sold them for a number well below the $45,000 mark,” he says.

Haselhorst made double the amount that he’d paid for them.

The second dealer, who purchased them from Haselhorst, quickly flipped the collection and sold it at the San Francisco Antiquarian Book Fair for an undisclosed number. The third buyer, also a dealer, had them priced at $25,000 at the recent New York Antiquarian Book Fair.

From these figures, we should estimate that Harper’s likely paid around $20,000 for the collection.

Harper’s Books’ brief description (and interpretation) of the collection reads:

Taken between 1977 and 1993. By far the largest vernacular archive of its kind we’ve seen, valuable for the insight it provides into Los Angeles gang, prison, and rap cultures. The first photo album contains 96 Polaroid photographs, many of which have been tagged (some in ink, others with the tag etched directly into the emulsion) by a wide swath of Los Angeles gang members. Most of the photos are of prisoners, with the majority of subjects flashing gang signs.

[…]

The second album has 44 photos and images from car magazines appropriated to make endpapers; the “frontispiece” image is of a late 30s-early 40s African-American woman, apparently the album-creator’s mother, captioned “Moms No. 1. With a Bullet for All Seasons.”

[…]

In addition, 170 loose color snapshots and 100 loose color Polaroids dating from 1977 through the early 1990s.

In my opinion, the little distinction Harper’s makes between gang culture and rap music culture is offensive. The two are not synonymous. This is an important and larger discussion, but not one to follow here in this article.

HOW SIGNIFICANT A COLLECTION IS THIS?

Harper’s is right on one thing. The newly named ‘Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive’ is a unique collection. Never before have I seen a collection this large. Visually, the text etched directly into the emulsion is a captivating feature of many of the polaroids.

We have seen plenty of vernacular prison photographs from the 19th and early to mid 20th century hit the market. Recently, a collection of 710 mugshots from the San Francisco Police Department made in the 1920’s sold twice within short-shrift. First for $2,150 in Portland, OR and then for $31,000 in New York just four months later! At the time of the sale, AntiqueTrader.com suggested it “may [have] set new record for album of vernacular photography.”

As a quick aside, and for the purposes of thinking out loud, might it be that polaroids that reference Southern California African American prison culture are – in the eyes of collectors and cultural-speculators – as exotic, distant and mysterious as sepia mugshots of last century? How does thirty years differ to one hundred when it comes to mythologising marginalised peoples? Does the elevation of gang ephemera from the gutter to traded high art mean anything? I argue, the market has found a ripe and right time to romanticise the mid-eighties and in particular real-life figures from the era that resemble the stereotypes of popular culture. It is in some ways a distasteful exploitation of people after-the-fact. Perhaps?

WHERE DOES THE $45,000 PRICE-TAG COME FROM?

Just because the so-called ‘Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive’ is rare, doesn’t mean similar collections do not exist, it may just mean they have not hit the market. This is, I argue, because no market exists … until now.

If the price tag seems crazy, it’s because it is. But consider this: one of the main guiding factors for valuations of art is previous sales of similar items. However, in the case of prison polaroids, there is no real discernible market. Harper’s is making the market, so they can name their price.

“All in all, it’s pretty crazy,” says Haselhorst, “especially when you think about how I bought it here in Portland over on 33rd, just a few miles from our gallery.”

All these details probably make up only the second chapter of this object’s biography. The first chapter was their making and ownership by the people in the photographs. Later chapters will be many. Time will tell whether later chapters will be attached to astronomical figures.

Harper’s suggests that rich “narrative arcs might be uncovered by careful research.” I agree. And these are importatn chapters to be written too.

I hope that more of these types of images with their narratives will emerge. If these types of vernacular prison images are to command larger and larger figures in the future, I hope that those who made them and are depiction therein make the sales and make the cash.

As it stands the speculation and rapid price increases, can be interpreted as easily as crass appropriation as it can connoisseurship. If these images deserve a $45,000 price tag, they deserve a vast amount of research to uncover the stories behind them. Who knows if the (presumed) new owner has the intent or access to the research resources required?

Along that same vein, here we identify a difference between the art market and the preservationists; between free trade capitalism and the efforts of museums, historians and academics; between those that trade rare items and those that are best equipped to do the research on rare items.

Whether speculative or accurate, the $45,000 price is way beyond the reach of museums. Photography and art dealers who are limber by comparison to large, immobile museums are working the front lines of preservation.

“Some might say that selling [images such as these] is exploitation, but a dealer’s willingness to monotize something like this is one form of cultural preservation,” argues Haselhorst. “If I had not been in a position to both see the collection’s significance and commodify it, albeit well below the final $45,000 mark, these photographs could have easily ended up in the trash.”

Loose Polaroids from the Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive as displayed by Harper’s Books at Paris Photo LA, Los Angeles, April, 2013.

A cover to one of the two albums that make up the Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive.

Dana Ullman, a Brooklyn-based photographer, has in recent years traveled back-and-forth to California; to Los Angeles’ Skid Row, to San Francisco’s Tenderloin, and to the San Joaquin Valley. The series’ title Another Kind Of Prison references the fact that many hardships of prison continue post-release and, furthermore, new challenges emerge. Ullman followed several women as they left prison and readjusted to life on the outside. For Ullman, the choice to go to California was logical.

“California is home to the world’s two largest women prisons and has an annual corrections budget of 10 billion dollars, the highest in the country, yet has limited reentry programs,” she says. “In California, there are about 12,000 women on parole. Unprepared once on parole, without money, housing or resources, institutionalized and isolated, these women find it difficult to regain hold of their lives.”

Over the past 15 years, the number of incarcerated women in prison increased by 203%, as compared to 77% for men. With such a rapid increase in prison populations, services within prisons have inevitably suffered. Ullman reports a lack of training, preparation and rehabilitation for the women she photographed.

Ullman is also keen to emphasize the common factors particular to female prisoners.

“62% of women in prison have children under 18. Many suffer from mental illness and have histories of sexual and physical abuse – 73% of women in prison have symptoms or are diagnosed with a mental illness compared to 55% of men in prison. 65% of women in state prisons are incarcerated for nonviolent drug, property, or public order offenses. Nearly one in three reported committing their offense to support a drug addiction. Many are battered women serving time for crimes related to their abuse,” Ullman writes.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Ullman wants to communicate the strength of the women who – at a particularly difficult junctures in life – have kindly let her into their lives.

“While some women have had difficult transitions, others have become inspirational community leaders – I want to show both sides in an effort to break stigma associated with incarceration.”

Dana Ullman and I share a belief that prisons are increasingly defining our society and economy.

“Another Kind Of Prison is more important then ever in exploring new strategies to better address the complex needs of present and former women prisoners who are often left out of the conversation,” says Ullman. “These stories, the needs and dreams of each woman in their own voice, illuminate the ‘revolving door’ created by poor public policies and lives fragmented by ignorance, poverty and by years, even lifetimes, of abuse. They will also help the public understand who these women are.”

Scroll down for a brief Q&A and a dozen more images. All images and captions by Dana Ullman.

Top image: LaKeisha Burton, 38, a poet and reentry advocate, was convicted as an adult at the age of 15. Ms. Burton served 17 and a half years in prison for shooting a gun into a crowd at the age of 15. She was convicted as an adult for attempted murder and received life plus 9 years. No one was killed or injured. The victim (with whom LaKeisha reconciled while both were serving time in prison), who killed someone, was released from CIW after 9 years. LaKeisha’s story represents the beginning of the disturbing increase in juveniles being tried as adults when many are completely capable of rehabilitation.

Above: On any given day women are paroled in California with a box of personal items, $200 or less in “gate money” and a bus ticket to Skid Row. Unprepared once out on parole, with no income, housing or resources, institutionalized and isolated, many women find it difficult to regain hold of their lives independently.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Clearly the success of a former-prisoner reentering society has a lot to do with their experience while locked up, but I feel in the past – for most people – dialogue about prison reform issues have been lumped in with dialogues about re-entry issues. That is to the detriment of both. It does seem though that, recently, re-entry has been recognised as its own vital step with its own set of issues to be explored. I’m thinking here of Convictions, Gabriela Bulisova’s excellent work in Washington D.C. and the forthcoming VII Photo’s documentary project and partnership with Think Outside The Cell.

Dana Ullman (DU): I am aware, too, of the increased focus on reentry [in photography] that really wasn’t there a few years ago. It is a difficult, complex and fragile issue to document because there are so many factors that lead to former prisoners’ success and failure, especially depending on where they live.

I am really happy to see Another Kind Of Prison getting some light because reentry is where one sees the emergence of all the issues that were not addressed while serving time, the societal factors that underline much of the mass incarceration today – sheer poverty, histories of abuse, racism and mental health. Once men and women are locked up and out of society, they are simplistically labeled “criminals” and the stigmas attached to poverty, abuse, race, mental health and crime are once again enforced.

PP: What are your hopes for the work?

DU: I envision, with some support, that Another Kind Of Prison will travel as an exhibition in community spaces such as libraries or ideally in county jails/state prisons where so many of these women (with very little support) are planning their release. There is one woman I interviewed who had no plan for even a place to sleep the night she got out. It was a random TV show featuring a transitional house that she saw one night, not her parole officer or a reentry prep class, that connected her to where she is now living. Women outside can really speak to those inside about their experiences. I have been making audio recordings of each woman’s story. I want the project to create a forum for discussion, rather than merely point out the problem.

PP: What’s next?

DU: I am not done with the project by any stretch. Documentary photography is tricky (and I am not a master of it by any means). I am following several, very fragile lives over time and waiting patiently for that “visual” moment that doesn’t always come. There is also so so much more I could do with some kind of funding, but that has been difficult, so I have to work with what I can. So for now, I hope to increase awareness of this experience shared by thousands of women in the USA with the general public and keeping plugging away at it making the work stronger.

In San Francisco, I was working very closely with the California Coalition of Women Prisoners who have used my work to support their own causes. I was very happy about that because the CCWP do a lot of direct services and support for these women. In New York, I am expanding the project to look a young 28-year-old upstate woman’s reentry process after being incarcerated at the age of 14 to try and get a younger person’s perspective.

I am going to Uganda this Fall where I will be working with the organization African Prisons Project documenting women in prison. I’ll also be collecting stories of people incarcerated and indefinitely-detained for homosexuality (for which the highest penalty is death). My work is quite capable of being a cross-cultural look at women and prison.

Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, California is one of two of the largest women’s prisons in the world; the second, Valley State Prison, is directly across the street.

Mary Shields embraces a long-time friend and advocate one week after being released from Central California Women’s Facility. Mary served 19 years for a crime related to domestic violence.

Mary Shields a week after her release from Central California Women’s Facility laughs with a friend after she had trouble understanding how to use a cell phone, which were not widely used twenty years ago.

LaKeisha Burton performs a spoken word piece at Chuco’s Justice Center, which serves as a youth and community space in Inglewood, California. Today, LaKeisha shares her story through spoken word performances and is dedicated to working with at-risk youth susceptible to gangs and the same injustices as she once experienced.

LaKeisha watches a youth group perform at Chuco’s Justice Center in Los Angeles, California. With her infectious optimism and self-determination, LaKeisha Burton displays almost nothing of her past; she lives, works and dates, as any women like her. Yet, these things are exceptional for someone who had lost, some might say had stolen, nearly two decades of the most developmental period in one’s life and with very little preparation thrust out into society. Ms. Burton says when she was released it was as if she were still 15 going on 16.

In the United States over 1.5 million children have a parent who is incarcerated.* 75% of women in prison are mothers and over half have children under the age of 18. Many children suffer lasting emotional effects of a parent’s incarceration, which can affect all areas as they develop into adults.

After cycling in and out of jail for crimes related to substance abuse, Jean Waldroup, 39, has found “home” at A New Way of Life, a transitional home for formerly incarcerated women that emphasizes keeping mothers and children together. For the last six months, Jean has maintained both her sobriety and role as mother to her son and daughter. Jean is the primary parent and she maintains a relationship with the children’s father.

A New Way of Life purchases homes in residential neighborhoods, giving a quieter, less institutional environment for families to rebuild relationships that may show signs of wear and tear after experiencing incarceration. Community-based organizations like A New Way of Life operate mostly under the radar with few resources and little public recognition despite their critical role in offering rehabilitation, family reunification and successful reentry.

Following her release, and to give her life structure, Molly volunteers to make lunch for clients at the behavioral health clinic she attends in San Francisco. Molly stills battles with drug addiction.

Molly on the bus. To avoid the caustic environment bubbling outside her building, Molly will ride Muni lines between Bayview-Hunter’s Point and Downtown San Francisco for hours. She tends to hide from nouns, that is people, places, and things. Molly’s mental health and substance abuse maintain instability and isolation in her life, some days are good, others hard.

A friend embraces Molly at a local community center.

Molly’s room at the Empress Hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. The first stable living she has had since the cycle of incarceration began in her life.

– – – –

*The advocacy group Children of Promise estimates the number of U.S. children with incarcerated parents at 2.7 million.

– – – –

DANA ULLMAN

Dana Ullman grew up in Portland, Oregon. She studied photojournalism at the Danish School of Journalism and holds a B.A. in Journalism from San Francisco State University. Dana currently lives in New York City photographing assignments and personal projects.

A New Way of Life Reentry Project is a non-profit organization in South Central Los Angeles with a core mission to help women and girls break the cycle of entrapment in the criminal justice system and lead healthy and satisfying lives.

California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP) is a grassroots social justice organization, with members inside and outside prison, that challenges the institutional violence imposed on women, transgender people, and communities of color by the prison industrial complex. CCWP prioritizes the leadership of the people, families, and communities most impacted in building this movement.

The African Prisons Project (APP) is a group of people passionately committed to improving access to healthcare, education, justice and community reintegration for male, female and juvenile prisoners in Africa.

I wanted to trace the physical and psychic contours of the world of these young people to see what they might reveal. Juvies is not only a document, but also a query about perception. Do we know who these young people are and what we are doing to them?

Ara Oshagan

The Open Society Documentary Photography Project launches Moving Walls 17 exhibit today. Ara Oshagan, one of the seven award recipients, alerted me to the New York launch and his inclusion, Juvies: A Collaborative Portrait of Juvenile Offenders.

Juvies is collaborative because often his images are accompanied by the handwritten texts of incarcerated young people. Frequently the writings focus on emotional ties, problems with self esteem, the powerlessness against a system. It makes sense then that many of Oshagan’s photographs are visually-fractured, detached.

Compositions of door-frames, window reflections, outside corridors and gestures to action the other side of barriers describe very literally the immediate limitations these young people face daily. Oshagan’s work is not to politicise, but to describe (as best that is possible in the manipulating medium of photography.)

Oshagan explains, “I did not meet any angry or tattoo-ridden kids decked out in the clothes and accessories that could mark them as members of the city’s gang culture. Rather, I found a group of ordinary young men and women who had signed up for a video production class. When I spoke to them, they were deferential. For them, candy was the “contraband” article they had brought to class. Some of the kids were interested in photography and told me about how they strove to learn white balance. I listened to one of the kids play Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” on [a keyboard]. And somehow I had come full circle: I had played that exact same piece to my own son the night before. Suddenly, the distance between the inside and the outside seemed to vanish into thin air, a vast gulf turned into an imperceptible chimera.”

PHOTOGRAPHING INSIDE

Before accompanying filmmaker friend, Leslie Neale* into Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall, Oshagan wasn’t an activist or particularly interested in prison reform. Oshagan admits the exposure to the system and young lives within was disorienting. From Oshagan’s artist statement:

“I was in a privileged place that allowed the perceptions that existed in my head to be confronted by the realities I was witnessing in the closed and misunderstood world of incarceration. What I was seeing was also raising issues that would not give me peace.”

“I can understand why Mayra might get life in prison for shooting her girlfriend from point blank range. But how could a combination of relatively minor charges result in the same life sentence for Duc, an 18-year-old who, despite having no prior convictions, was convicted in a shooting crime that resulted in no injuries and in which he did not pull the trigger? And why did Peter – a 17-year-old piano prodigy and poet – get 12 years in adult prison for a first time assault and breaking and entering offense? Why is the justice system so harsh on kids who clearly have potential?”

PHOTOGRAPHING OUTSIDE

In addition to the walls, the guards, the other incarcerated people, the yards, the bunk beds, Oshagan also photographed families and communities left behind as well as the courts and victims. Sadly, I cannot present these images here but consider them essential in Oshagan’s “layered photographic narrative”.

These young people cannot be ignored. Our actions, just as theirs have ramifications both sides of the walls.

Two weeks ago the Supreme Court of the United States of America changed law, ruling life imprisonment without parole (LWOP) for a non-capital offense by a juvenile was to be removed from the books. Get past the fact that such harsh punishment was illogic and cruel and one soon arrives at the maddening circumstances of some of Oshagan’s subjects, Duc.

High school student Duc was arrested for driving a car from which a gun was shot. Although no one was injured, Duc was not a member of a gang, had no priors and was 16 years old, he received a sentence of 35 years to life

Again, to quote Oshagan, “Do we know who these young people are and what we are doing to them?”

* Oshagan did the B-Roll for Neale’s documentary film Juvies, whose own words about the juvenile detention system are worth taking in.

BIOGRAPHY

Born into a family of writers, Ara Oshagan studied literature and physics, but found his true passion in photography. A self-taught photographer, his work revolves around the intertwining themes of identity, community, and aftermath.

Aftermath is the main impetus for his first project, iwitness, which combines portraits of survivors of the Armenian genocide of 1915 with their oral histories. Issues of aftermath and identity also took Oshagan to the Nagorno-Karabakh region in the South Caucasus, where he documented and explored the post-war state of limbo experienced by Armenians in that mountainous and unrecognized region. This journey resulted in a project that won an award from the Santa Fe Project Competition in 2001, and will be published by powerHouse Books in 2010 as Father Land, a book featuring Oshagan’s photographs and an essay by his father.

Oshagan has also explored his identity as member of the Armenian diaspora community in Los Angeles. This project, Traces of Identity, was supported by the California Council for the Humanities and exhibited at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in 2004 and the Downey Museum of Art in 2005. Oshagan’s work is in the permanent collections of the Southeast Museum of Photography, the Downey Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art in Armenia.

MOVING WALLS 17

Also supported by the Open Society Documentary Photography Project are Jan Banning, Mari Bastashevski, Christian Holst, Lori Waselchuk & Saiful Huq Omi and The Chacipe Youth Photography Project.