You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Pelican Bay’ tag.

8 June 2012: Crescent City, CA. California State Prison: Pelican Bay Prison. Examples of kites (messages) written by prisoners. These were discovered before they were smuggled out.

Too often since writing this post, I have lamented the dearth of images of solitary confinement. We have suffered as a society from not seeing. A few years back a change began. Solitary confinement became an anchor issue to the prison reform and abolition movements. Thanks largely to activist and journalist inquiry we’ve seen more and more images of solitary confinement emerge. However, news outlets still relying on video animation to tell stories, which would indicate images remain scarce and at a premium.

Robert Gumpert has just updated his website with photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison. Some are from the Secure Housing Unit (SHU) that has been the center of years of controversy and the locus of 3 hunger strikes since the summer of 2011. Other photographs are from the general population areas of the supermaximum security facility.

Click the “i” icon at the top right of Gumpert’s gallery to see caption info, so that you can be sure which wing of this brutal facility is in each photograph.

Despite seeing Gumpert regularly, I am still not aware of exactly how these images came about. I think Gumpert was on assignment but the publication didn’t, in the end, pull the trigger. Their loss is our gain. Gumpert provides 33 images. It’s a strange mix. I’d go as far to say stifled. Everything is eerily still under dank light. We encounter, at distance, a cuffed prisoner brought out for the camera. Gumpert’s captions indicate interviews took place, but there are no prisoners’ quotes. In a deprived environment it makes sense that Gumpert focuses on signs — they point toward the operations and attitudes more than a portrait of officer or prisoner does, I think.

The gallery opens with images from the SHU and then moves into the ‘Transition Housing Unit’ which is where prisoners who have signed up for the Step-Down Program are making their transition from assigned gang-status to return to the general population. Critics of the Step-Down Program say it is coercive and serves the prisons’ need more than the prisoners.

Note: It doesn’t matter how the prisoner identifies — if the prison authority has classed a prisoner as a gang member it is very difficult to shake the label. The Kafkaesque irreversibility of many CDCR assertions was what led to a growth in use of solitary in the California prisons.

8 June 2012: Crescent City, CA. California State Prison: Pelican Bay Prison. A SHU cell occupied by two prisoners. Cell is about 8×10 with no windows. Bunks are concrete with mattress roles. When rolled up the bunk serves at a seat and table.. Cones on the wall are home made speakers using ear-phones for the TV or radio. Speakers are not allowed.

I’ve picked out three images from Gumpert’s 33 that I think are instructive in different ways. While we may be amazed by the teeny writing of a prisoner in his kites (top) we should also be aware that these were shown to Gumpert to re-enforce the point that prisoners in solitary are incorrigible. The suggestion is that these words are a threat and we should be fearful. But we cannot know if we cannot read them fully. How good is your eyesight? Click the image to see it larger.

As for the “speakers” made of earphones and cardboards cylinders! Can those really amplify sound in any meaning full way?

And finally, to the image below. I thought the quotation marks in the church banner (below) were yet another case of poor prison signage grammar, but reading the caption and learning that the chapel caters for 47 faiths, makes “LORD’S” entirely applicable. Not a single lord but the widest, most ill-defined, catch-all version of a lord (higher presence/Yahweh/Gaia/Sheba/fog-spirit/Allah/fill-in-the-blank) in a prison that is all but god-forsaken.

See the full gallery.

8 June 2012: Crescent City, CA. California State Prison: Pelican Bay Prison. The religion room serving 47 different faiths and beliefs.

The NYCLU created a mock prison cell to show what life is like in solitary confinement. Kathleen Horan/WNYC

Today resumed a hunger strike by the prisoners of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison SHU (Secure Housing Unit). In solidarity, prisoners across the nation have also joined.

The main issue at hand is solitary confinement. Namely, its longterm use. UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Mendez, stated that any time over 15 days in solitary confinement constitutes torture. Yet California prisoners have been caged in solitary for 10 to 20 years or more. In addition, the prisoners kept under solitary confinement ask for nutritious food and the same educational programming accessible to prisoners in the general populations of state prisons.

Solitary confinement is an invisible cancer to those outside the system and a terror to those within it.

The prisoners — who refer to themselves at The Short Corridor Collective — are returning to protest that began two years ago. Neither Phase One (July/August 2011) and Phase Two (Sept/Oct 2011) secured the policy changes desired, despite promises from the California Department of Corrections to address the specific issues and reasonable demands made. In 2011, over 6,000 California prisoners went on hunger and work strike making it one of the largest peaceful protests in U.S. prison history.

The Pelican Bay State Prison SHU Short Corridor Collective state:

Our decision does not come lightly. For the past 2 years we’ve patiently kept an open dialogue with state officials, attempting to hold them to their promise to implement meaningful reforms, responsive to our demands. For the past seven months we have repeatedly pointed out CDCR’s failure to honor their word—and we have explained in detail the ways in which they’ve acted in bad faith and what they need to do to avoid the resumption of our protest action.

Five core demands

1. Eliminate group punishments. Instead, practice individual accountability. When an individual prisoner breaks a rule, the prison often punishes a whole group of prisoners of the same race. This policy has been applied to keep prisoners in the SHU indefinitely and to make conditions increasingly harsh.

2. Abolish the debriefing policy and modify active/inactive gang status criteria. Prisoners are accused of being active or inactive participants of prison gangs using false or highly dubious evidence, and are then sent to longterm isolation (SHU). They can escape these tortuous conditions only if they “debrief,” that is, provide information on gang activity. Debriefing produces false information (wrongly landing other prisoners in SHU, in an endless cycle) and can endanger the lives of debriefing prisoners and their families.

3. Comply with the recommendations of the US Commission on Safety and Abuse in Prisons (2006) regarding an end to longterm solitary confinement. This bipartisan commission specifically recommended to “make segregation a last resort” and “end conditions of isolation.” Yet as of May 18, 2011, California kept 3,259 prisoners in SHUs and hundreds more in Administrative Segregation waiting for a SHU cell to open up. Some prisoners have been kept in isolation for more than thirty years.

4. Provide adequate food. Prisoners report unsanitary conditions and small quantities of food that do not conform to prison regulations. There is no accountability or independent quality control of meals.

5. Expand and provide constructive programs and privileges for indefinite SHU inmates. The hunger strikers are pressing for opportunities “to engage in self-help treatment, education, religious and other productive activities…” Currently these opportunities are routinely denied, even if the prisoners want to pay for correspondence courses themselves. Examples of privileges the prisoners want are: one phone call per week, and permission to have sweatsuits and watch caps. (Often warm clothing is denied, though the cells and exercise cage can be bitterly cold.) All of the privileges mentioned in the demands are already allowed at other SuperMax prisons (in the federal prison system and other states).

You can download full text document of the demands here.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Sign the petition.

Involvement in the July 13th Mass Mobilization!

Plan a solidarity action!

Follow! On Twitter and on Facebook

Use your imagination and your skills; talk to your family and friends about it, and maybe provide them with a handful of shocking facts about the psychological torture that is solitary ? (See below)

Don’t get despondent, get angry.

WHAT IS SOLITARY CONFINEMENT?

In California, nearly 12,000 imprisoned people spend 23 hours-a-day living in a concrete cell smaller than a large bathroom. Across the United states it is conservatively estimated that 20,000 people are in solitary every day. It could be as high as 70,000; it depends on definitions related to time and contact.

In California solitary cells have no windows, no access to fresh air or sunlight. People in solitary confinement exercise an hour a day in a cage the size of a dog run. They are not allowed to make any phone calls to their loved ones. They cannot touch family members who often travel days for a 90 minute visit. They are not allowed to talk to other imprisoned people. They are denied all educational programs, and their reading materials are censored.

UNFATHOMABLE SCALE AND WIDESPREAD USE

“The [psychological and cognitive effects of long term isolation] is not something that’s easy to study, and not something that prison systems are eager to have people look at,” says Craig Haney, psychology professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz, who notes that the widespread use of solitary is a very modern phenomena.

We have an overwhelmingly crowded prison system in which the mandate to rehabilitate and provide activities for prisoners was suspended at the same time as the prison system became overcrowded. Not surprisingly, prison systems faced with this influx of prisoners, and lacking the rewards they once had to manage and control prisoner behavior, turned to the use of punishment. And one big punishment is the threat of long-term solitary confinement. They’ve used it without a lot of forethought to its consequences. That policy needs to be rethought.

Writing for the New Yorker (Hellhole) in 2009, physician Atul Gawande quoted extensively from Haney’s research and added:

After months or years of complete isolation, many prisoners “begin to lose the ability to initiate behavior of any kind—to organize their own lives around activity and purpose. Chronic apathy, lethargy, depression, and despair often result. . . . In extreme cases, prisoners may literally stop behaving” (Haney). [They] become essentially catatonic.

Keep yourself informed; keep progressing; keep honest; follow news on the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity website.

In solidarity, Pete.

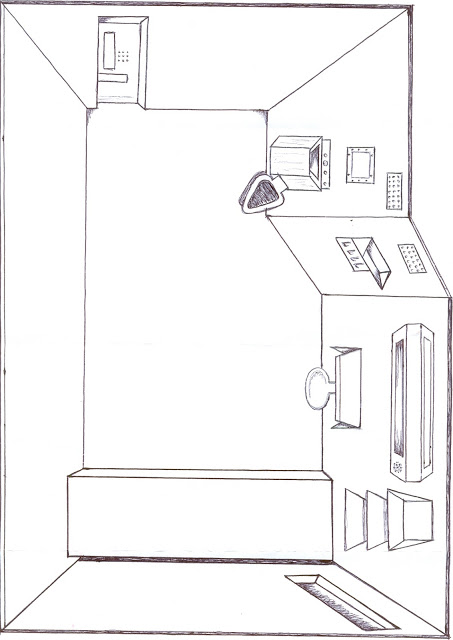

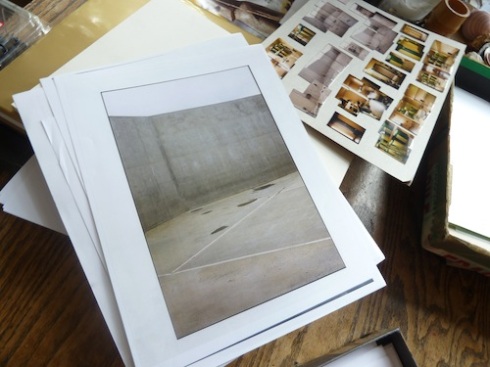

The image above was drawn by Katherine Fontaine, a San Francisco based architect, prison-questioner, friend to all, and book-art-space-collective co-runner.

“There are very few pictures of SHUs. The last drawing that was found at the Freedom Archives in San Francisco was from when Reagan was the Governor of California,” says Fontaine.

With solitary confinement, such a hot news topic, Fontaine was compelled to sketch when she realised there were very few images of solitary cells in circulation.

“I was given the few photos that exist from other similar prisons and a diagram that was used in a previous court case drawn by a prisoner while in an SHU at Pelican Bay. The drawing is what I came up with from the materials I was given,” explains Fontaine who hopes her drawing of a Pelican Bay State Prison Secure Housing Unit (SHU) will be used — in media materials and campaigns — by any organizations protesting solitary confinement.

Fontaine’s commitment to make reliable sketches of prison spaces and apparatus was spurred by a chance encounter with some fellow professionals in an unlikely place. She was among a crowd outside the Central California Women’s Facility protesting overcrowding inside the prison.

Fontaine noticed a person within the crowd with a sign that read ‘Architects Against Overcrowding In Prisons.’ On the back of the sign was www.ADPSR.org. The acronym stands for Architects, Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility. Despite her day job as an architect, ADPSR was not a group with whom she was familiar. Upon reading the statement for the Prison Alternatives Initiative, one of ADPSR’s projects, Fontaine was all-in.

ADPSR state:

“Our prison system is both a devastating moral blight on our society and an overwhelming economic burden on our tax dollars, taking away much needed resources from schools, health care and affordable housing. The prison system is corrupting our society and making us more threatened, rather than protecting us as its proponents claim. It is a system built on fear, racism, and the exploitation of poverty. Our current prison system has no place in a society that aspires to liberty, justice, and equality for all. As architects, we are responsible for one of the most expensive parts of the prison system, the construction of new prison buildings. Almost all of us would rather be using our professional skills to design positive social institutions such as universities or playgrounds, but these institutions lack funding because of spending on prisons. If we would rather design schools and community centers, we must stop building prisons.”

Fontaine’s sketches will regularly appear in Actually People Quarterly, partly to inform as partly as a means to focus her thoughts.

“People need to see them,” she says. “Also it was such a powerful thing for me to draw that SHU cell. I wonder if anyone else can have a similar feeling just by looking at it or if I just feel so changed by it because I drew it. Maybe it is because I’ve spent years of my life drawing, studying, measuring and designing spaces that in actually creating that image I imagined that actual space so much more clearly than I had before? To imagine being an architect and *designing* that space is incomprehensible to me.”

Incidentally, ADPSR was recently featured on the excellent podcast 99% Invisible in an episode called An Architect’s Code, following mainly the activities of Raphael Sperry, ADPSR’s founder.

Below is Fontaine’s sketch of cage used routinely within the California prison system. The cages are sometimes to hold prisoners during transfer between units but, increasingly, used for group *therapy* — an oxymoron if there ever was one.

I’d also like to take this opportunity to share the work of some other determined prison sketchers, some of whom are prisoners.

From the website, Solitary Watch:

One of the most prolific and talented artists in solitary is 60-year-old Thomas Silverstein, who has been in extreme isolation in the federal prison system under a “no human contact” order for going on 30 years. (He describes the experience here.) His artwork appears on this site. It includes meticulously detailed drawings of some of the cells he has occupied, including one pictured below, which is designed (with built-in shower and remote-controlled door to an exercise yard) so that he never has to leave it or encounter anyone at all.

Next is this cell in Ohio, drawn by prisoner Greg Curry.

And finally, Ojore Lutalo has made some of the most politically charged prison art I’ve ever seen. Below, an isolation cell, and very below, Control Units, 1992.

When depicting prisons and their abuses there is no hierarchy of medium; sketches, photos, videos and oral testimony conspire to deliver a fuller picture. I will say though that these narrative rich drawings are more powerful than many photographs I come across.

Isolation exercise yard, Security Housing Unit, Pelican Bay, Crescent City, California, a supermax-type control, high security facility said to house California’s most dangerous prisoners. © Richard Ross

Solitary confinement is in the news … for lots of reasons – a lawsuit brought by prisoners against the Federal Bureau of Prisons; a lawsuit brought by 10 prisoners in solitary against the state of California; a June Senate hearing on the psychological and human rights implications of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons (which included the fabrication of a replica sized AdSeg cell in the courtroom); an ACLU report pegging solitary as human rights abuse; a NYCLU report showing arbitrary use of solitary, a NYT Op-Ed by Lisa Guenther; the rising use of solitary at immigration detention centres; and the United Nations’ announcement that solitary is torture.

Recently, journalists from across America have contacted me looking for photographs of solitary confinement to accompany their article. I could only think of three photographers – one of whom wishes to remain anonymous; another, Stefan Ruiz is not releasing his images yet; which leaves Richard Ross‘ work which is well known.

Stefan Ruiz’ photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison, CA made in 1995 for use as court evidence. (See full Prison Photography interview with Ruiz here.)

With a seeming paucity, I went in search of other images. I found an image of a “therapy session” by Lucy Nicholson from her Reuters photo essay Inside San Quentin. A scene that has been taken to task by psychologist and political image blogger Michael Shaw.

Shane Bauer took a camera inside Pelican Bay for his recent Mother Jones report on solitary confinement.

Rich Pedroncelli for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Pelican Bay has been hosting media tours and welcoming journalists in the past year – partly due to public pressure and partly through a strategic shift by the CDCR to appear to be responding to public outcry. Maybe the courts have had a say, too?

© Lucy Nicholson / Reuters. Prisoners of San Quentin’s AdSeg unit in group therapy. (Source)

© Shane Bauer. Pelican Bay SHU cell. (Source)

© Shane Bauer. CA CDCR employees show investigative journalist Shane Bauer the Pelcian Bay SHU “Dog run.” (Source)

Correctional Officer Lt. Christopher Acosta is seen in the exercise area in the Secure Housing Unit at the Pelican Bay State Prison near Crescent City, Calif., Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2011. State prison officials allowed the media to tour Pelican’ Bay’s secure housing unit, known as the SHU, where inmates are isolated for 22 1/2 hours a day in windowless, soundproofed cells to counter allegations of mistreatment made during an inmate hunger strike last month. Photo: Rich Pedroncelli, AP/SF (Source)

The amount of visual evidence still seems limited. It’s not that reporting on solitary confinement is lax or missing. To the contrary, I’ve listed at the foot of this piece some excellent recent journalism on the issue form the past year. We lack images.

Look Inside A Supermax a piece done with text and not images is typical of the invisibility of these sites. National Geographic tried a couple of years to bring solitary confinement to a screen near you. ABC News journalist Dan Harris spent the “two worst days of his life” in solitary to report the issue.

Why do we need to see these super-locked facilities? Well, depending on your sources there are between 15,000 and 80,000 people held in isolation daily (definitions of isolation differ). My conservative estimate is that 20,000 men, women and children are held in single occupancy cells 23 hours a day.

Gabriel Reyes, prisoner at Pelican Bay SHU writes about his experience for the San Francisco Chronicle:

“For the past 16 years, I have spent at least 22 1/2 hours of every day completely isolated within a tiny, windowless cell. […] The circumstances of my case are not unique; in fact, about a third of Pelican Bay’s 3,400 prisoners are in solitary confinement; more than 500 have been there for 10 years, including 78 who have been here for more than 20 years.”

Solitary confinement is a “living death”; an isolating “gray box” and “life in a black hole.” Imagine locking yourself in a space the size of your bathroom for 23 hours a day. As James Ridgeway, currently the most prolific and reliable reporter on American solitary confinement, writes:

“A growing body of academic research suggests that solitary confinement can cause severe psychological damage, and may in fact increase both violent behavior and suicide rates among prisoners. In recent years, criminal justice reformers and human rights and civil liberties advocates have increasingly questioned the widespread and routine use of solitary confinement in America’s prisons and jails, and states from Maine to Mississippi have taken steps to reduce the number of inmates they hold in isolation.”

The over zealous and under regulated use of solitary confinement to control risk and populations within U.S. prisons is a cancer within already broken corrections systems. I’m posting a few more image that Google images afforded me – but I urge caution – these are just a glimpse and may not be indicative of solitary/SHU conditions. Windows are a rarity in solitary despite three images below showing them.

The main reason I’m posting here is to ask for your help in sourcing all the photography of U.S. solitary confinement we can. Please post links in the comments section and I’ll add them to the article as time goes on.

SELECT IMAGES

© Alice Lynd. Front view of cell D1-119. Todd Ashker has been in a Security Housing Unit (SHU) for more than 25 years, since August 1986, and in the Pelican Bay SHU nearly 22 years, since May 2, 1990. “The locked tray slot is where I get my food trays, mail.” (Source)

A typical special housing unit (SHU) cell for two prisoners, in use at Upstate Correctional Facility and SHU 20.0.s in New York. Photo: Unknown. (Source)

Bunk in Secure Housing Unit cell, Pelican Bay, California © Rina Palta/KALW. (Source)

Solitary Confinement at the Carter Youth Facility. Since the arrival of the girls’ program at Carter, the administration has created a new seclusion cell. This cell contains no pillow, sheet, pillow case or blanket. In fact, there is nothing in the cell other than a mattress, which was added after numerous requests from the monitor. Girls are routinely placed in this room for “time out.” Photo: Maryland Juvenile Justice Monitoring Unit. (Source)

© Rina Palta, KALW. “More than 3,000 prisoners in California endure inhuman conditions in solitary confinement.” This photo, taken in August 2011 of a corridor inside the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at Pelican Bay State Prison, illustrated Amnesty’s report. (Source)

© National Geographic. In Colorado State Penitentiary 756 inmates are held in “administrative segregation” alone in their cells for 23 hours a day. 5 times a week they are allowed into the rec room where they can exercise and breath fresh air through a grated window. (Source)

FURTHER READING

Eddie Griffin, prisoner in s Supermax prison in Marion, IL writes about “Breaking Men’s Minds” [PDF.]

Boxed In NYCLU campaign and report with resources and video against use of solitary confinement. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

The Gray Box, an investigative journalism series and film about solitary across the U.S., by Susan Greene. (Dart Society) HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

ACLU – Stop Solitary Confinement – Resources – HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

ACLU _ State specific reports on solitary confinement

Andrew Cohen’s three part series on “The American Gulag” (Atlantic)

Atul Gawande’s take on the psychological impacts of solitary confinement (New Yorker)

Sharon Shalev, author of Supermax: Controlling Risk Through Solitary Confinement, here writes about conditions. (New Humanist)

The shocking abuse of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons (Amnesty)

SOLITARY ELSEWHERE ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

Interview with Isaac Ontiveros, Director of Communications with Critical Resistance, about Pelican Bay solitary and community activism.

The invention of solitary confinement.

RIGO 23, Michelle Vignes, the Black Panthers and Leonard Peltier

Chilean Miners, Russian Cosmonauts and 20,000 American Prisoners

Robert King, of the Angola 3, writes for the Guardian

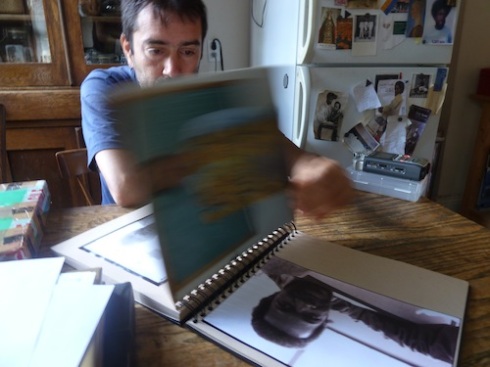

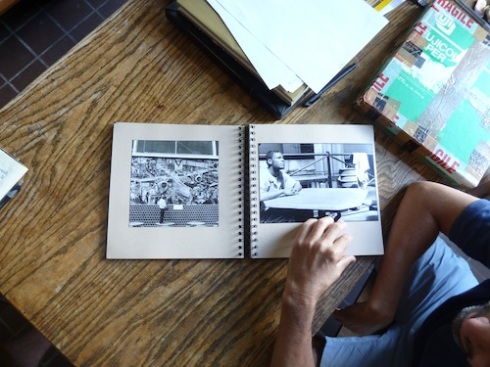

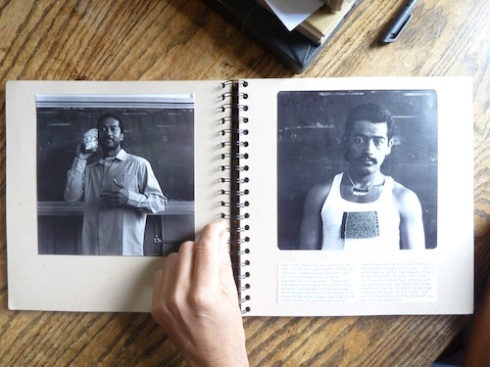

In the kitchen of his Brooklyn home, Ruiz flicks through his “portfolio” of prison images.

Stefan Ruiz has made photographs inside San Quentin State Prison, Soledad Prison and the notorious maximum-security Pelican Bay State Prison. His photography from within California’s prisons was not accomplished by conventional methods; at no time was Ruiz on press assignment; making documentary work or running a photography workshop.

Ruiz worked for seven years as an art instructor at San Quentin, during which time he regularly made photographic records of individual artworks. He took some portraits of his students on the side. He got inside Pelican Bay as a court-appointed photographer making photographs for use as trial evidence.

It’s a bit of a family affair. Ruiz’s mother, a professor at UC Santa Cruz, was teaching art at Soledad. Ruiz had studied Islamic art in West Africa and went to deliver a talk to Muslim prisoners at Soledad. He delivered the same lecture later at San Quentin, at which time he was introduced to the art program coordinated by the William James Association.

Ruiz’s father is a criminal defense attorney, who in the mid nineties represented a prisoner at Pelican Bay. Ruiz was the case-for-defense’s chosen photographer, documenting conditions the of client’s confinement.

In addition to his photography, Ruiz made sketches, collected his students’ artwork, and acquired objects typical of prison culture. When he showed me a photograph of a DIY prison tattoo gun, I asked, “Is that something an inmate showed you or is it something that had been confiscated?”

“It’s something I have,” Ruiz replied.

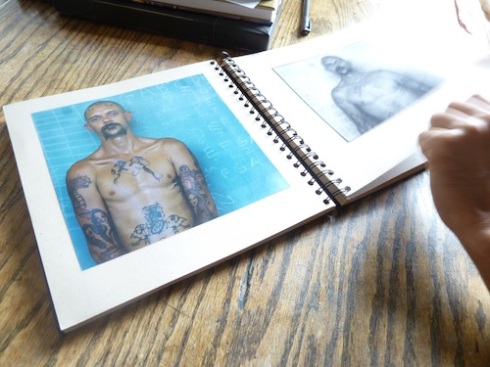

The first photos Ruiz made inside were portraits of Soledad prison-artists holding their work. He took six rolls of film. At the age of 23, Ruiz began teaching art at San Quentin. One of his students had been a student of his mother’s at Soledad years prior. Prison-art hangs in Ruiz’ house and he has collected mug-shots for years.

In the mid-nineties, Ruiz cobbled together a photo “notebook” of his pictures of people and vernacular art. He keeps it in an old Fujifilm box bound with packing tape. “I used to take this with me everywhere; it was my portfolio.”

From humble and organic beginnings, Ruiz is now one of the most respected portrait and editorial photographers in America. Until recently he had never spoken about his experiences in California’s prisons. We sat down in his kitchen to unpack his memories and his homebrew portfolio.

Q&A

PP: Your mother introduced you to prison-life?

SR: My mother organized exhibitions of the prisoners’ artwork. I helped out by taking photos of the artwork and making slides of their work. Some of that would go to William James Association to help them appeal for funding or for entry into competitions. That’s how I got cameras into the prison at first. Whenever I took a camera into a prison it was legal, and it was generally to photograph some type of art object.

PP: Of your prison work, it is your portraits that are known, however minimally, in the public sphere. I wasn’t aware of them until you were featured on VICE TV’s Picture Perfect.

SR: There are more photographs than just portraits. I taught at San Quentin for so long, and my boss had such a good relationship with the officials that gave access, that we were allowed to do quite a few things.

The first portraits I did were of the guys in my mother’s art class at Soledad who were to be involved in an exhibition. The way we were allowed to make portraits was to say, since they couldn’t make it to their show, their portrait would.

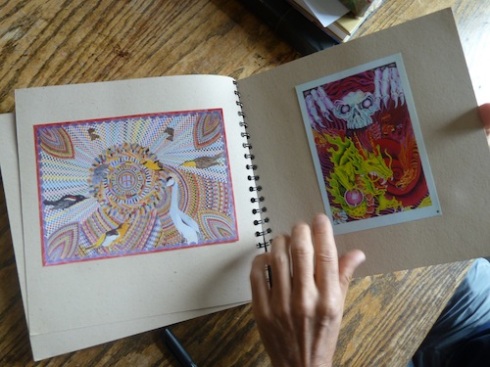

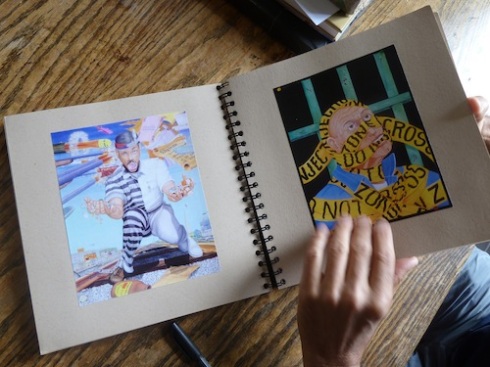

Prisoner art

Prisoner art

PP: Describe the art program.

SR: My boss played bass and the main emphasis of the art class was music but there were two visual artists who taught and I was one. The other was Patrick Maloney, who I guess is still teaching there. Patrick would also teach on Death Row. Sometimes, I would fill for him or accompany him on Death Row.

PP: How did you find working on death row?

SR: You move along the tiers and talk [through bars] to students individually, whereas on the mainline they come out their cells and they come to you.

There are two different sections of death row. In the first, there are a couple of tiers of just death row inmates. You’d need the key to get on the tier, and then you’d go from cell to cell, depending on who was part of the program. There might be three or four guys on a single tier. They had to buy their own supplies but through William James we also gave them supplies. Mostly you’d spend time talking to them. Each day, they might get half an hour outside their cell.

In the other section, the prisoners could leave their cells and go to a common space with some tables. There you could have two or three people in the class. That seemed like a better place to be on death row. The tiers are quite dark. Five tiers. And the other side is just open. One of our students was executed. He had killed a shopkeeper and his wife robbing a store in Los Angeles. He was a good student.

PP: Your mother was a professor at Santa Cruz, teaching art classes at Soledad. Those two institutions have a long and significant relationship going back to the protests and counter culture of the late sixties, Black Pantherism, and the book Soledad Prison: University of the Poor (1975) which was a collaboration between UCSC students and prisoners at Soledad.

PP: You gave a talk to Muslim students at Soledad, then to Muslim students at San Quentin and then you began in the art program. That trajectory explains your path but not your motivations. Why did you decide that leading arts education with prisoners was something you wanted to commit to multiple times a week, and eventually over seven years.

SR: Because it is interesting. I have to say; I think I learnt more from them than they learnt from me.

My father is a lawyer in criminal defense and labor law. His family is Mexican and he’s pretty liberal, so I grew up with that element too. Teaching art in prison was an activity that brought together both sides of my family.

PP: A context in which prison teaching is not a radical act?

SR: My mother was more or less a hippie. My father couldn’t really be one, he was just trying to assimilate, but he was definitely liberal. Growing up in Northern California at that time it was more of a norm than not to be on the left. To do things such as teaching in prison was not considered wild. There was no whole movement about victims’ rights as there is now.

Fair enough. There’s a lot of bad people in prison and some people who deserve to be there but …

When I was a kid, my parents were involved in a free school. We grew up in the country growing organic food. That was way before the trends of today. We composted everything; we weren’t allowed to have plastic bags for lunch. We had wax paper and baked our own bread.

The thing is the prison was interesting to me. At San Quentin they allowed me to take keys. The room where I taught art used to be a laundry room. There was a bunch of people that got murdered there, I guess in the seventies or eighties so they closed it down and eventually opened it up as an art room.

There was never a guard in our room. It was two levels but we would teach on the lower level. The closest guard was in what we would call the max-shack – a checkpoint, probably about 30 yards outside the door. I was really young when I was teaching there and a lot of the guys were way bigger than me. It was interesting to learn how to navigate that. There were anywhere from 5 to 15 people in my class. 15 would be a little bit hectic. Often we’d just get someone from the yard and have him come and sit. Students who wanted could draw him, and if not, they could work on other projects.

PP: Were any of them reluctant to paint or draw other prisoners? My experience teaching art in prison was that collectively they decided it was “suspect”, for want of a better term, to spend the time and energy painting another prisoner. Most of them made portraits of wives, girlfriends or children in a devotional way so to paint another prisoner made no sense to them and was in fact considered strange. They felt other prisoners would misconstrue it as a gesture of adoration or romantic attraction to the subject and that is something most guys wanted to avoid.

SR: No, most of them were into it. They didn’t have to do it but one thing is that since cameras aren’t allowed in prison you can make money if you can draw well, by drawing portraits, usually by copying photographs of prisoners’ family members. If you’re good you can make money. It’s like a throwback to an era before the camera; I can draw fairly realistically and that kind of saved me when I was in there because …

PP: … there’s a lot of respect attached to that ability.

SR: Yes. They’d give me a lot of shit and then we’d start drawing and it’d be fine. I generally had quite a few lifers in the class, because they are the ones who are more serious – eventually they decide to try and use their time. Young guys, who were only in for a little while, might joke around. The older guys kept the class in order.

PP: At what other times did you use your camera?

SR: There’s some really famous murals in San Quentin. I photographed them all.

PP: Was that the San Quentin administration that asked you to do that, or was it William James or was it self-initiated?

SR: My boss, Aida de Arteaga and I, decided it was a good thing to do. There are four dining halls. It used to be one huge one but it was divided because they were worried about riots. Three walls. Six sides on which the murals were painted. A Mexican-American inmate who had been busted, I think, for selling heroin painted the murals in the fifties. When I was still there, he came back to San Quentin, for the first time since his incarceration.

Photos from the San Quentin Prison dining halls. One of Ruiz’ students stands in front of the famous murals.

PP: In Photographs Not Taken you close with a bittersweet statement in which you said while you managed to take photos you still thought about the ones you weren’t allowed to take in such a “visually rich environment.” Did the staff or inmates think of their environment as visually rich?

SR: Obviously, most of the prisoners wanted to be out of there. I’m sure quite a few of the guards would like to have taken photos. Some did. Various guards had cameras for different reasons.

PP: What reasons?

SR: To photograph events. I photographed some of those too. We had concerts in the main yard, which is pretty impressive at San Quentin when you are down there with all the inmates. One time we had Ice Cube come in. On that billing, they had a white performer, a Hispanic performer and Ice Cube was the black performer. The administration has to play it like that.

Ice Cube performed in one of the dining halls and that was pretty crazy. You could see the guards were quite nervous. Some of the inmates were getting fired up. I don’t think they had another concert like that.

The prison liked the art program quite a lot and there were some guards who were supportive of our classes. Guards will either make things easy or hard for you. Basically, I think we were lucky for a lot of the time; we had people who were kind, trusted us, let us do more.

The thing about being there for so long is that you got know people fairly well. Especially being in a classroom when you’re with students for three or four hours at a time just drawing and talking. The thing that struck me was that I had a few guys who were lifers and had been in for 20 to 25 years; that’s a pretty crazy concept, especially now given all the changes that have happened, specifically with technology. I am sure – unless they were using them with their jobs within the prison – none of them had used a computer.

PP: Did you ever think there was an opportunity for you to do a photography workshop?

SR: The administration didn’t want us to do that at all. Even toward the end, they started to question me taking drawings out of the prison because many of them were realistic to the point that you could identify people in the drawings!

PP: What did the administration think of the portraits you did manage to take?

SR: They didn’t see most of them. They had signed-off on me doing photography, but they didn’t necessarily see the photographs. We got releases form the guys too. Guards might follow me round for a while, but I can take photos for days and bore the shit out of anyone. [Laughs].

I’ve probably got one of the best [records of the murals]. They were done on 4×5. I even did some on 8×10. I got in there at different times. Once, I’d used a Linhof 617 lens and camera on a commercial job, then I got access and so I used it in the prison.

PP: Did I hear that the Smithsonian has come to some sort of agreement, where by if and when San Quentin is demolished, they’ll remove and preserve the murals?

SR: They’ve been saying that for years, but I don’t know. The murals depict the history of California. The prisoners love the cable-car because the perspective is right so as you walk around it works.

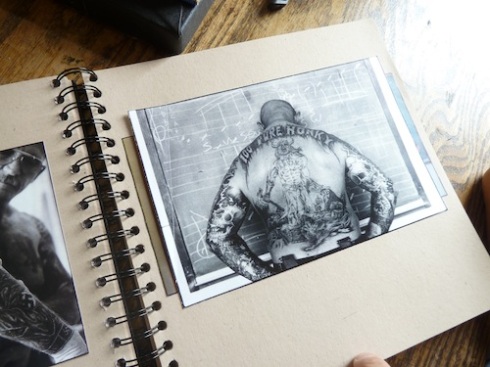

“This guy before he took his shirt off warned me that his tattoos were considered some of the most racist in the prison. There’s the SS helmet skeletons.” Tattoos read ‘100% Honky’ and ‘Aryan’.

Ruiz used a chalkboard as a backdrop, “I liked the color and I liked the reference to education.” Some prisoners shaved their heads ready for the shoot. “They knew I was bringing in the camera so they prepared,” says Ruiz.

PP: It seems like the prison administration’s policy toward camera use was ad hoc?

SR: I photographed in Pelican Bay and Tehachapi, but I actually did that through a court order. My father was representing a prisoner who the CDC said was one of the heads of the Northern Mexican mafia and that he was ordering murders from his cell in Pelican Bay.

In Pelican Bay I had to use the prison’s cameras; they wouldn’t let me take in any of my own equipment, except film. This was 1995. They held on to the film, processed it, and then gave everything to me, negatives and all. The images are a bit … the lenses were a bit crazy. It’s not what I would’ve used but it was fine.

In Tehachapi, I got to use one camera and one lens. Both were mine.

PP: What was your brief for the court order?

SR: I had to photograph the cells and so the reason these photos are joined together is that they only allowed me the one lens.

Ruiz photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison, CA made in 1995 for use as court evidence.

4/4/95, Pelican Bay – “The defendant was in one of these cells.”

“Pelican Bay is obviously freaky.”

“This is the yard at Tehachapi. This is a common area, these are the cells.”

PP: It’s because of the connection through your father that you got the court ordered gig?

SR: As a defense attorney, he was allowed to bring in his own photographer. As an art teacher, I’d actually spent more time inside of prisons than my father had. Normally, he would only go to a visiting room where he would talk to his client. Whereas, I used to go on tiers, I went in cells. There were times at San Quentin when I was totally unsupervised and there were times it felt a little freaky.

PP: Were any limits placed or pre-agreements made by the courts on your photographs to limit their circulation, or are they just yours?

SR: They’re just mine.

PP: Is there a reason why you’ve not shared them widely yet?

SR: There are some that I considered might be a bit sensitive and I didn’t want to get my boss into trouble in any way. The photographs from Pelican Bay and Tehachapi are fine. The ones from San Quentin; she’d help me get the camera in. We had an understanding. I wasn’t going to screw her over.

It’s more important for me to be cool with her than it is to profit from the photos. I’ve done fine with photography without having ever shown these. I probably could’ve done a book with these and with some of the writing and artwork I have a long time ago, but I’ve never been about just promoting myself at all costs without taking others into consideration.

By now, enough time has passed. I’m going through everything. I think I have enough for a book. I have boxes of stuff that just accumulated.

PP: How did all of this work and exposure across three Californian prisons inform the rest of your career?

SR: I always knew I was going to do art. I didn’t know I was going to do photography. I always thought I’d be a painter. The thing that I learned? I learnt that if I couldn’t take any photos, I would collect things!

I took my portfolio everywhere. I got jobs off of the stuff but I never let it out of my hands. You’re the first person to have photographed it, with the exception of the VICE crew who put it in their video. I’m okay with that now. I always guarded it.

I met the guys who were doing COLORS magazine in the late nineties and it definitely influenced them. It influenced their ‘Prison’ issue (June, 2002). I was actually supposed to go to Gaza for COLORS, but the Israelis had bombed the prison right before I was due to leave, so the trip was cancelled. So, I’ve definitely used this stuff to my advantage.

PP: Did you ever give prints to the prisoners?

SR: I’d give them stuff but we kept it low key because I didn’t want any trouble for the program.

PP: Did the guys you taught appreciate that San Quentin had more programs than most prisons?

SR: They liked San Quentin. It’s an old prison. It has a lot of nooks and crannies. There are weird things that go on there that you wouldn’t get in a modern prison.

There was the old hospital built in the 19th century and out of brick. It was structurally unsound after the earthquake and left empty. They’d let certain prisoners go in there at their own risk. The deputy warden or someone in authority allowed one of my students to set up an art studio in there. And he had it for a couple of years! You wouldn’t get that at a lot of other places.

PP: Your photographs form a weird mix.

SR: I’ve always thought it was valid because it was about what I could get and how I could get it.

Soledad prisoners.

PP: Do you think prison systems in the U.S. are racist?

SR: If 11% of California’s population is Black but then at least 36% of the prison population is Black something’s not proportional. That says something about this society. Obviously the system can be racist, but it is also classist. You have a hell of a lot more poor people in prison than you do wealthy people and that’s because wealthy people can afford lawyers.

There weren’t many well educated guys in my classes. They’re obviously smart guys who could do all sorts but they weren’t well educated. I had a blonde white guy who I asked him to read something one time, not even thinking that he didn’t know how to read. It was a horrible thing for him and, of course, for me. I didn’t expect it at all. After that he started taking some of the high school classes and learnt to read.

Prisons are a control thing. [Upon release] if you have people who can’t travel, can’t get housing and can’t vote you can keep a whole population controlled. You can keep a whole population one little step away from being thrown straight back into prison.

PP: So the prison system is failing?

SR: I definitely think some people should be in prison.

There was a child molester who was quite collectible. People like to collect his art. He creeped me out. He made drawings of the kids he had killed from newspaper clippings. I took photographs of them, but I didn’t know that’s what they were until he explained them to me later. He had a scrapbook and the first 20 pages were pictures of Hillary Clinton smiling and then after that it was all these pictures of kids. Innocent pictures – many of them from National Geographic, but when you know what he was about, it’s pretty disturbing.

There’s some fucked up people in the world.

But I also saw, all the time, guys in prison for stupid drugs convictions and I think that is just a waste. The three strikes law was foolish. Keeping someone in prison, which at the time cost something like $30,000 – I’m sure it’s more now – is just a waste of money. You can give people education with that money to help them get better jobs.

I used to go to the visitor center a lot. You’d see the damage being done when families would come up from Los Angeles for the day. Wives would go in and the kids would stay in the guesthouse for the day. The separation of families when they have to travel so far [to where loved ones are imprisoned] is harsh.

Obviously, I believe in education over other things. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have done what I did.

Stefan Ruiz

Ruiz was born in San Francisco, and studied painting and sculpture at the University of California (Santa Cruz) and the Accademia di Belle Arti (Venice, Italy). He took up photography while in West Africa, documenting Islam’s influence on traditional West African art. He taught art at San Quentin State Prison from 1992-1998, and began to work professionally as a photographer in 1994. He has worked editorially for magazines including Colors (for whom he was Creative Director, 2003-04), The New York Times Magazine, L’uomo Vogue, Wallpaper*, The Guardian Weekend, Telegraph Magazine and Rolling Stone. His award winning advertising campaigns include Caterpillar, Camper, Diesel, Air France and Costume National.

© Richard Ross

Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City, California is one of the most oppressive regimes of the U.S. prison system. It was designed to control and isolate the growing gang affiliations within California prisons following the CDCR’s massive expansion throughout the 1980s. It opened in 1989 and established THE model for maximum security prisons in states across the U.S.

Pelican Bay Prison specialises in solitary confinement. When photographer Richard Ross documented prisons as part of his Architecture of Authority project he went to Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay and Pelican Bay.

The most segregated inmates spend 22 and half hours in a cell barely larger then your bedrooms or bathrooms. For the other 1 and a half hours they occupy a concrete pen for “exercise.”

Pelican Bay is notorious for it’s history of violence and despair. It is also, according to Christian Parenti, a boon for small town economics.

It is a god-forsaken hole.

The most isolated prisoners have put together a strike plan. Yes, they have demands, but more than that they want to make a point about the inhumane and invisible conditions they inhabit. Yes, many of them have committed heinous crimes but cooping them up like dogs serves only to increase tension, anger and danger.

BACKGROUND AND DEMANDS

Prisoners in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at Pelican Bay State Prison have called for an indefinite hunger strike as of July 1, 2011 to protest the cruel and inhumane conditions of their imprisonment. The hunger strike was organized by prisoners in an unusual show of racial unity. The prisoners developed five core demands.

California Prison Focus supports these prisoners and their very reasonable demands, and calls on Governor Jerry Brown, CDCR Secretary Matthew Cate, and Pelican Bay State Prison Warden Greg Lewis to implement these changes. California Prison Focus has also joined “Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity,” a coalition of grassroots human rights activist groups in the Bay Area supporting the demands of the prisoners participating in the hunger strike.

Briefly the five core demands of the prisoners are:

1. Eliminate group punishments. Instead, practice individual accountability. When an individual prisoner breaks a rule, the prison often punishes a whole group of prisoners of the same race. This policy has been applied to keep prisoners in the SHU indefinitely and to make conditions increasingly harsh.

2. Abolish the debriefing policy and modify active/inactive gang status criteria. Prisoners are accused of being active or inactive participants of prison gangs using false or highly dubious evidence, and are then sent to longterm isolation (SHU). They can escape these tortuous conditions only if they “debrief,” that is, provide information on gang activity. Debriefing produces false information (wrongly landing other prisoners in SHU, in an endless cycle) and can endanger the lives of debriefing prisoners and their families.

3. Comply with the recommendations of the US Commission on Safety and Abuse in Prisons (2006) regarding an end to longterm solitary confinement. This bipartisan commission specifically recommended to “make segregation a last resort” and “end conditions of isolation.” Yet as of May 18, 2011, California kept 3,259 prisoners in SHUs and hundreds more in Administrative Segregation waiting for a SHU cell to open up. Some prisoners have been kept in isolation for more than thirty years.

4. Provide adequate food. Prisoners report unsanitary conditions and small quantities of food that do not conform to prison regulations. There is no accountability or independent quality control of meals.

5. Expand and provide constructive programs and privileges for indefinite SHU inmates. The hunger strikers are pressing for opportunities “to engage in self-help treatment, education, religious and other productive activities…” Currently these opportunities are routinely denied, even if the prisoners want to pay for correspondence courses themselves. Examples of privileges the prisoners want are: one phone call per week, and permission to have sweatsuits and watch caps. (Often warm clothing is denied, though the cells and exercise cage can be bitterly cold.) All of the privileges mentioned in the demands are already allowed at other SuperMax prisons (in the federal prison system and other states).

The Pelican Bay hunger strikers have support form the other SuperMax in California Corcoran Bay Prison.

Herman Krieger – stalwart of the Oregon photography community and Eugene resident – is a self-made specialist in the art of captioning. However, more than his quirky words, I appreciate the great lengths he goes to in order to document sites of the prison industrial complex.

View from Boise Gun Club, New Idaho State Prison. Herman Krieger

Krieger described the circumstances of the series, “The idea of making a photo essay on prisons and their settings came after driving from Tucson to Phoenix. The view of the prison in Florence, Arizona struck me as an odd thing in the middle of the landscape. At that time I was only looking at churches for the series, Churches ad hoc“.

With Lifetime Mortgage, Vacaville, California. Herman Krieger

“I then made some photos of prisons in Oregon and California. Others were made during a trip by car from Oregon to New York. I would have made a longer series, but I was too often hassled by prison guards who noticed me pointing a camera at a prison. They claimed that it was illegal to take a photo of the public building from a public road, and threatened to confiscate my film”, explained Krieger.

Room Without a View, Pelican Bay, California. Herman Krieger

Pelican Bay was opened in 1989 and constructed purposefully to hold the most violent offenders, usually gang members. Along with Corcoran State Prison, in the late 1980s, Pelican Bay ushered in a new era of Supermax facilities in California. They are remote (Pelican Bay is just miles from the Oregon border) and they are expansive. Their distant locations prohibit regular visits from inmates’ family members – a detail probably not lost on the CDCR authorities who sought to transfer, contain and stifle the aggressions of Californian urban areas.

Bayside View, San Quentin, California. Herman Krieger

Having lived in San Francisco for three years, the policies, activities, controversies and executions at San Quentin State Prison were always well reported in the Bay Area press. One of the most frustrating repetitions of the San Quentin coverage was the journalist’s compulsion – regardless of the story – to remind readers of the huge land value of San Quentin and the opportunities for real estate on San Quentin Point.

Open for Tourists, Old State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger.

Over the Hill, New State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger

America is a large country. It should be no surprise that prisons are built in isolated areas – it makes economic sense to build on non-agricultural hinterlands and it makes strategic sense to purpose build facilities on flat open ground. More significantly, to locate these “people warehousing units” out of society’s view, allows convenient cultural and political ignorance for the authorities & citizens that sentenced men and women to America’s new breed of prison.

Krieger’s photographs summarise the key intrigues and detachment “we” feel as those excluded from prison operation and experience. Krieger, in some of his other images, gets closer to the prison walls and yet I deliberately featured these six prints precisely because of their disconnect. What terms, other than those of distance and exclusion, can we legitimately use in dialogue about contemporary prisons?