You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Stefan Ruiz’ tag.

Isolation exercise yard, Security Housing Unit, Pelican Bay, Crescent City, California, a supermax-type control, high security facility said to house California’s most dangerous prisoners. © Richard Ross

Solitary confinement is in the news … for lots of reasons – a lawsuit brought by prisoners against the Federal Bureau of Prisons; a lawsuit brought by 10 prisoners in solitary against the state of California; a June Senate hearing on the psychological and human rights implications of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons (which included the fabrication of a replica sized AdSeg cell in the courtroom); an ACLU report pegging solitary as human rights abuse; a NYCLU report showing arbitrary use of solitary, a NYT Op-Ed by Lisa Guenther; the rising use of solitary at immigration detention centres; and the United Nations’ announcement that solitary is torture.

Recently, journalists from across America have contacted me looking for photographs of solitary confinement to accompany their article. I could only think of three photographers – one of whom wishes to remain anonymous; another, Stefan Ruiz is not releasing his images yet; which leaves Richard Ross‘ work which is well known.

Stefan Ruiz’ photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison, CA made in 1995 for use as court evidence. (See full Prison Photography interview with Ruiz here.)

With a seeming paucity, I went in search of other images. I found an image of a “therapy session” by Lucy Nicholson from her Reuters photo essay Inside San Quentin. A scene that has been taken to task by psychologist and political image blogger Michael Shaw.

Shane Bauer took a camera inside Pelican Bay for his recent Mother Jones report on solitary confinement.

Rich Pedroncelli for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Pelican Bay has been hosting media tours and welcoming journalists in the past year – partly due to public pressure and partly through a strategic shift by the CDCR to appear to be responding to public outcry. Maybe the courts have had a say, too?

© Lucy Nicholson / Reuters. Prisoners of San Quentin’s AdSeg unit in group therapy. (Source)

© Shane Bauer. Pelican Bay SHU cell. (Source)

© Shane Bauer. CA CDCR employees show investigative journalist Shane Bauer the Pelcian Bay SHU “Dog run.” (Source)

Correctional Officer Lt. Christopher Acosta is seen in the exercise area in the Secure Housing Unit at the Pelican Bay State Prison near Crescent City, Calif., Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2011. State prison officials allowed the media to tour Pelican’ Bay’s secure housing unit, known as the SHU, where inmates are isolated for 22 1/2 hours a day in windowless, soundproofed cells to counter allegations of mistreatment made during an inmate hunger strike last month. Photo: Rich Pedroncelli, AP/SF (Source)

The amount of visual evidence still seems limited. It’s not that reporting on solitary confinement is lax or missing. To the contrary, I’ve listed at the foot of this piece some excellent recent journalism on the issue form the past year. We lack images.

Look Inside A Supermax a piece done with text and not images is typical of the invisibility of these sites. National Geographic tried a couple of years to bring solitary confinement to a screen near you. ABC News journalist Dan Harris spent the “two worst days of his life” in solitary to report the issue.

Why do we need to see these super-locked facilities? Well, depending on your sources there are between 15,000 and 80,000 people held in isolation daily (definitions of isolation differ). My conservative estimate is that 20,000 men, women and children are held in single occupancy cells 23 hours a day.

Gabriel Reyes, prisoner at Pelican Bay SHU writes about his experience for the San Francisco Chronicle:

“For the past 16 years, I have spent at least 22 1/2 hours of every day completely isolated within a tiny, windowless cell. […] The circumstances of my case are not unique; in fact, about a third of Pelican Bay’s 3,400 prisoners are in solitary confinement; more than 500 have been there for 10 years, including 78 who have been here for more than 20 years.”

Solitary confinement is a “living death”; an isolating “gray box” and “life in a black hole.” Imagine locking yourself in a space the size of your bathroom for 23 hours a day. As James Ridgeway, currently the most prolific and reliable reporter on American solitary confinement, writes:

“A growing body of academic research suggests that solitary confinement can cause severe psychological damage, and may in fact increase both violent behavior and suicide rates among prisoners. In recent years, criminal justice reformers and human rights and civil liberties advocates have increasingly questioned the widespread and routine use of solitary confinement in America’s prisons and jails, and states from Maine to Mississippi have taken steps to reduce the number of inmates they hold in isolation.”

The over zealous and under regulated use of solitary confinement to control risk and populations within U.S. prisons is a cancer within already broken corrections systems. I’m posting a few more image that Google images afforded me – but I urge caution – these are just a glimpse and may not be indicative of solitary/SHU conditions. Windows are a rarity in solitary despite three images below showing them.

The main reason I’m posting here is to ask for your help in sourcing all the photography of U.S. solitary confinement we can. Please post links in the comments section and I’ll add them to the article as time goes on.

SELECT IMAGES

© Alice Lynd. Front view of cell D1-119. Todd Ashker has been in a Security Housing Unit (SHU) for more than 25 years, since August 1986, and in the Pelican Bay SHU nearly 22 years, since May 2, 1990. “The locked tray slot is where I get my food trays, mail.” (Source)

A typical special housing unit (SHU) cell for two prisoners, in use at Upstate Correctional Facility and SHU 20.0.s in New York. Photo: Unknown. (Source)

Bunk in Secure Housing Unit cell, Pelican Bay, California © Rina Palta/KALW. (Source)

Solitary Confinement at the Carter Youth Facility. Since the arrival of the girls’ program at Carter, the administration has created a new seclusion cell. This cell contains no pillow, sheet, pillow case or blanket. In fact, there is nothing in the cell other than a mattress, which was added after numerous requests from the monitor. Girls are routinely placed in this room for “time out.” Photo: Maryland Juvenile Justice Monitoring Unit. (Source)

© Rina Palta, KALW. “More than 3,000 prisoners in California endure inhuman conditions in solitary confinement.” This photo, taken in August 2011 of a corridor inside the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at Pelican Bay State Prison, illustrated Amnesty’s report. (Source)

© National Geographic. In Colorado State Penitentiary 756 inmates are held in “administrative segregation” alone in their cells for 23 hours a day. 5 times a week they are allowed into the rec room where they can exercise and breath fresh air through a grated window. (Source)

FURTHER READING

Eddie Griffin, prisoner in s Supermax prison in Marion, IL writes about “Breaking Men’s Minds” [PDF.]

Boxed In NYCLU campaign and report with resources and video against use of solitary confinement. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

The Gray Box, an investigative journalism series and film about solitary across the U.S., by Susan Greene. (Dart Society) HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

ACLU – Stop Solitary Confinement – Resources – HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

ACLU _ State specific reports on solitary confinement

Andrew Cohen’s three part series on “The American Gulag” (Atlantic)

Atul Gawande’s take on the psychological impacts of solitary confinement (New Yorker)

Sharon Shalev, author of Supermax: Controlling Risk Through Solitary Confinement, here writes about conditions. (New Humanist)

The shocking abuse of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons (Amnesty)

SOLITARY ELSEWHERE ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

Interview with Isaac Ontiveros, Director of Communications with Critical Resistance, about Pelican Bay solitary and community activism.

The invention of solitary confinement.

RIGO 23, Michelle Vignes, the Black Panthers and Leonard Peltier

Chilean Miners, Russian Cosmonauts and 20,000 American Prisoners

Robert King, of the Angola 3, writes for the Guardian

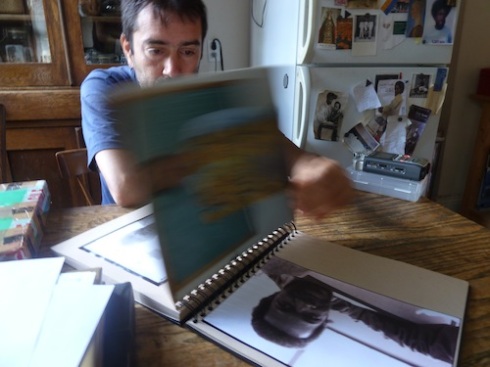

In the kitchen of his Brooklyn home, Ruiz flicks through his “portfolio” of prison images.

Stefan Ruiz has made photographs inside San Quentin State Prison, Soledad Prison and the notorious maximum-security Pelican Bay State Prison. His photography from within California’s prisons was not accomplished by conventional methods; at no time was Ruiz on press assignment; making documentary work or running a photography workshop.

Ruiz worked for seven years as an art instructor at San Quentin, during which time he regularly made photographic records of individual artworks. He took some portraits of his students on the side. He got inside Pelican Bay as a court-appointed photographer making photographs for use as trial evidence.

It’s a bit of a family affair. Ruiz’s mother, a professor at UC Santa Cruz, was teaching art at Soledad. Ruiz had studied Islamic art in West Africa and went to deliver a talk to Muslim prisoners at Soledad. He delivered the same lecture later at San Quentin, at which time he was introduced to the art program coordinated by the William James Association.

Ruiz’s father is a criminal defense attorney, who in the mid nineties represented a prisoner at Pelican Bay. Ruiz was the case-for-defense’s chosen photographer, documenting conditions the of client’s confinement.

In addition to his photography, Ruiz made sketches, collected his students’ artwork, and acquired objects typical of prison culture. When he showed me a photograph of a DIY prison tattoo gun, I asked, “Is that something an inmate showed you or is it something that had been confiscated?”

“It’s something I have,” Ruiz replied.

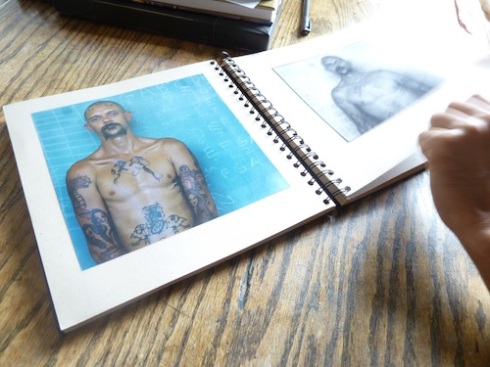

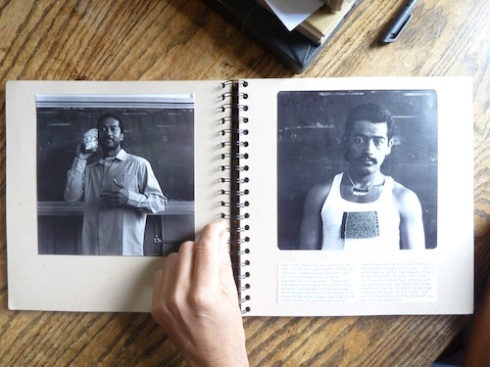

The first photos Ruiz made inside were portraits of Soledad prison-artists holding their work. He took six rolls of film. At the age of 23, Ruiz began teaching art at San Quentin. One of his students had been a student of his mother’s at Soledad years prior. Prison-art hangs in Ruiz’ house and he has collected mug-shots for years.

In the mid-nineties, Ruiz cobbled together a photo “notebook” of his pictures of people and vernacular art. He keeps it in an old Fujifilm box bound with packing tape. “I used to take this with me everywhere; it was my portfolio.”

From humble and organic beginnings, Ruiz is now one of the most respected portrait and editorial photographers in America. Until recently he had never spoken about his experiences in California’s prisons. We sat down in his kitchen to unpack his memories and his homebrew portfolio.

Q&A

PP: Your mother introduced you to prison-life?

SR: My mother organized exhibitions of the prisoners’ artwork. I helped out by taking photos of the artwork and making slides of their work. Some of that would go to William James Association to help them appeal for funding or for entry into competitions. That’s how I got cameras into the prison at first. Whenever I took a camera into a prison it was legal, and it was generally to photograph some type of art object.

PP: Of your prison work, it is your portraits that are known, however minimally, in the public sphere. I wasn’t aware of them until you were featured on VICE TV’s Picture Perfect.

SR: There are more photographs than just portraits. I taught at San Quentin for so long, and my boss had such a good relationship with the officials that gave access, that we were allowed to do quite a few things.

The first portraits I did were of the guys in my mother’s art class at Soledad who were to be involved in an exhibition. The way we were allowed to make portraits was to say, since they couldn’t make it to their show, their portrait would.

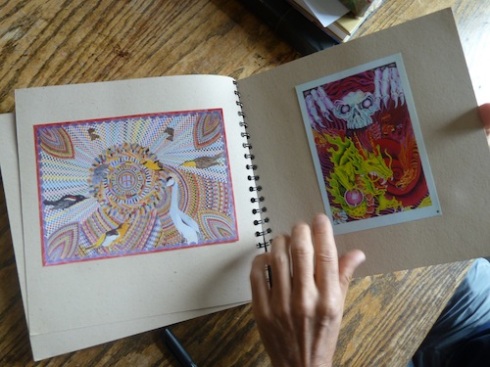

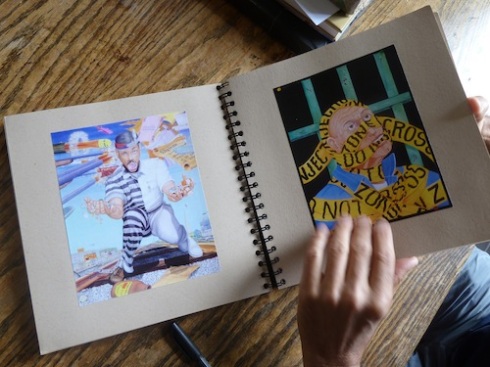

Prisoner art

Prisoner art

PP: Describe the art program.

SR: My boss played bass and the main emphasis of the art class was music but there were two visual artists who taught and I was one. The other was Patrick Maloney, who I guess is still teaching there. Patrick would also teach on Death Row. Sometimes, I would fill for him or accompany him on Death Row.

PP: How did you find working on death row?

SR: You move along the tiers and talk [through bars] to students individually, whereas on the mainline they come out their cells and they come to you.

There are two different sections of death row. In the first, there are a couple of tiers of just death row inmates. You’d need the key to get on the tier, and then you’d go from cell to cell, depending on who was part of the program. There might be three or four guys on a single tier. They had to buy their own supplies but through William James we also gave them supplies. Mostly you’d spend time talking to them. Each day, they might get half an hour outside their cell.

In the other section, the prisoners could leave their cells and go to a common space with some tables. There you could have two or three people in the class. That seemed like a better place to be on death row. The tiers are quite dark. Five tiers. And the other side is just open. One of our students was executed. He had killed a shopkeeper and his wife robbing a store in Los Angeles. He was a good student.

PP: Your mother was a professor at Santa Cruz, teaching art classes at Soledad. Those two institutions have a long and significant relationship going back to the protests and counter culture of the late sixties, Black Pantherism, and the book Soledad Prison: University of the Poor (1975) which was a collaboration between UCSC students and prisoners at Soledad.

PP: You gave a talk to Muslim students at Soledad, then to Muslim students at San Quentin and then you began in the art program. That trajectory explains your path but not your motivations. Why did you decide that leading arts education with prisoners was something you wanted to commit to multiple times a week, and eventually over seven years.

SR: Because it is interesting. I have to say; I think I learnt more from them than they learnt from me.

My father is a lawyer in criminal defense and labor law. His family is Mexican and he’s pretty liberal, so I grew up with that element too. Teaching art in prison was an activity that brought together both sides of my family.

PP: A context in which prison teaching is not a radical act?

SR: My mother was more or less a hippie. My father couldn’t really be one, he was just trying to assimilate, but he was definitely liberal. Growing up in Northern California at that time it was more of a norm than not to be on the left. To do things such as teaching in prison was not considered wild. There was no whole movement about victims’ rights as there is now.

Fair enough. There’s a lot of bad people in prison and some people who deserve to be there but …

When I was a kid, my parents were involved in a free school. We grew up in the country growing organic food. That was way before the trends of today. We composted everything; we weren’t allowed to have plastic bags for lunch. We had wax paper and baked our own bread.

The thing is the prison was interesting to me. At San Quentin they allowed me to take keys. The room where I taught art used to be a laundry room. There was a bunch of people that got murdered there, I guess in the seventies or eighties so they closed it down and eventually opened it up as an art room.

There was never a guard in our room. It was two levels but we would teach on the lower level. The closest guard was in what we would call the max-shack – a checkpoint, probably about 30 yards outside the door. I was really young when I was teaching there and a lot of the guys were way bigger than me. It was interesting to learn how to navigate that. There were anywhere from 5 to 15 people in my class. 15 would be a little bit hectic. Often we’d just get someone from the yard and have him come and sit. Students who wanted could draw him, and if not, they could work on other projects.

PP: Were any of them reluctant to paint or draw other prisoners? My experience teaching art in prison was that collectively they decided it was “suspect”, for want of a better term, to spend the time and energy painting another prisoner. Most of them made portraits of wives, girlfriends or children in a devotional way so to paint another prisoner made no sense to them and was in fact considered strange. They felt other prisoners would misconstrue it as a gesture of adoration or romantic attraction to the subject and that is something most guys wanted to avoid.

SR: No, most of them were into it. They didn’t have to do it but one thing is that since cameras aren’t allowed in prison you can make money if you can draw well, by drawing portraits, usually by copying photographs of prisoners’ family members. If you’re good you can make money. It’s like a throwback to an era before the camera; I can draw fairly realistically and that kind of saved me when I was in there because …

PP: … there’s a lot of respect attached to that ability.

SR: Yes. They’d give me a lot of shit and then we’d start drawing and it’d be fine. I generally had quite a few lifers in the class, because they are the ones who are more serious – eventually they decide to try and use their time. Young guys, who were only in for a little while, might joke around. The older guys kept the class in order.

PP: At what other times did you use your camera?

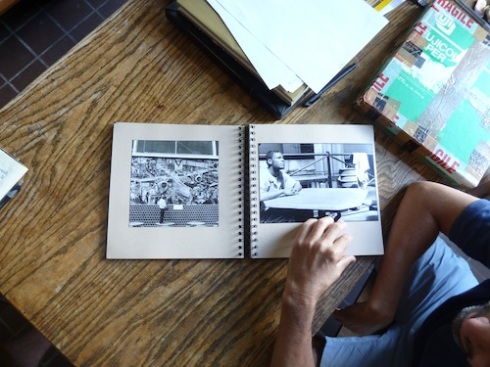

SR: There’s some really famous murals in San Quentin. I photographed them all.

PP: Was that the San Quentin administration that asked you to do that, or was it William James or was it self-initiated?

SR: My boss, Aida de Arteaga and I, decided it was a good thing to do. There are four dining halls. It used to be one huge one but it was divided because they were worried about riots. Three walls. Six sides on which the murals were painted. A Mexican-American inmate who had been busted, I think, for selling heroin painted the murals in the fifties. When I was still there, he came back to San Quentin, for the first time since his incarceration.

Photos from the San Quentin Prison dining halls. One of Ruiz’ students stands in front of the famous murals.

PP: In Photographs Not Taken you close with a bittersweet statement in which you said while you managed to take photos you still thought about the ones you weren’t allowed to take in such a “visually rich environment.” Did the staff or inmates think of their environment as visually rich?

SR: Obviously, most of the prisoners wanted to be out of there. I’m sure quite a few of the guards would like to have taken photos. Some did. Various guards had cameras for different reasons.

PP: What reasons?

SR: To photograph events. I photographed some of those too. We had concerts in the main yard, which is pretty impressive at San Quentin when you are down there with all the inmates. One time we had Ice Cube come in. On that billing, they had a white performer, a Hispanic performer and Ice Cube was the black performer. The administration has to play it like that.

Ice Cube performed in one of the dining halls and that was pretty crazy. You could see the guards were quite nervous. Some of the inmates were getting fired up. I don’t think they had another concert like that.

The prison liked the art program quite a lot and there were some guards who were supportive of our classes. Guards will either make things easy or hard for you. Basically, I think we were lucky for a lot of the time; we had people who were kind, trusted us, let us do more.

The thing about being there for so long is that you got know people fairly well. Especially being in a classroom when you’re with students for three or four hours at a time just drawing and talking. The thing that struck me was that I had a few guys who were lifers and had been in for 20 to 25 years; that’s a pretty crazy concept, especially now given all the changes that have happened, specifically with technology. I am sure – unless they were using them with their jobs within the prison – none of them had used a computer.

PP: Did you ever think there was an opportunity for you to do a photography workshop?

SR: The administration didn’t want us to do that at all. Even toward the end, they started to question me taking drawings out of the prison because many of them were realistic to the point that you could identify people in the drawings!

PP: What did the administration think of the portraits you did manage to take?

SR: They didn’t see most of them. They had signed-off on me doing photography, but they didn’t necessarily see the photographs. We got releases form the guys too. Guards might follow me round for a while, but I can take photos for days and bore the shit out of anyone. [Laughs].

I’ve probably got one of the best [records of the murals]. They were done on 4×5. I even did some on 8×10. I got in there at different times. Once, I’d used a Linhof 617 lens and camera on a commercial job, then I got access and so I used it in the prison.

PP: Did I hear that the Smithsonian has come to some sort of agreement, where by if and when San Quentin is demolished, they’ll remove and preserve the murals?

SR: They’ve been saying that for years, but I don’t know. The murals depict the history of California. The prisoners love the cable-car because the perspective is right so as you walk around it works.

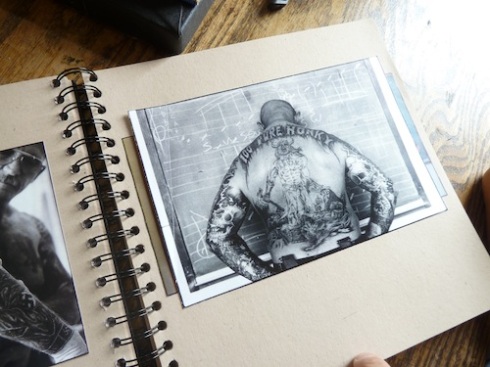

“This guy before he took his shirt off warned me that his tattoos were considered some of the most racist in the prison. There’s the SS helmet skeletons.” Tattoos read ‘100% Honky’ and ‘Aryan’.

Ruiz used a chalkboard as a backdrop, “I liked the color and I liked the reference to education.” Some prisoners shaved their heads ready for the shoot. “They knew I was bringing in the camera so they prepared,” says Ruiz.

PP: It seems like the prison administration’s policy toward camera use was ad hoc?

SR: I photographed in Pelican Bay and Tehachapi, but I actually did that through a court order. My father was representing a prisoner who the CDC said was one of the heads of the Northern Mexican mafia and that he was ordering murders from his cell in Pelican Bay.

In Pelican Bay I had to use the prison’s cameras; they wouldn’t let me take in any of my own equipment, except film. This was 1995. They held on to the film, processed it, and then gave everything to me, negatives and all. The images are a bit … the lenses were a bit crazy. It’s not what I would’ve used but it was fine.

In Tehachapi, I got to use one camera and one lens. Both were mine.

PP: What was your brief for the court order?

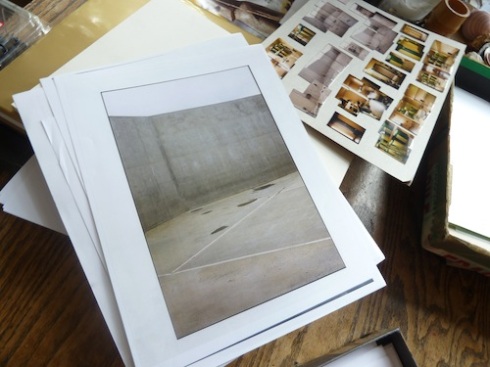

SR: I had to photograph the cells and so the reason these photos are joined together is that they only allowed me the one lens.

Ruiz photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison, CA made in 1995 for use as court evidence.

4/4/95, Pelican Bay – “The defendant was in one of these cells.”

“Pelican Bay is obviously freaky.”

“This is the yard at Tehachapi. This is a common area, these are the cells.”

PP: It’s because of the connection through your father that you got the court ordered gig?

SR: As a defense attorney, he was allowed to bring in his own photographer. As an art teacher, I’d actually spent more time inside of prisons than my father had. Normally, he would only go to a visiting room where he would talk to his client. Whereas, I used to go on tiers, I went in cells. There were times at San Quentin when I was totally unsupervised and there were times it felt a little freaky.

PP: Were any limits placed or pre-agreements made by the courts on your photographs to limit their circulation, or are they just yours?

SR: They’re just mine.

PP: Is there a reason why you’ve not shared them widely yet?

SR: There are some that I considered might be a bit sensitive and I didn’t want to get my boss into trouble in any way. The photographs from Pelican Bay and Tehachapi are fine. The ones from San Quentin; she’d help me get the camera in. We had an understanding. I wasn’t going to screw her over.

It’s more important for me to be cool with her than it is to profit from the photos. I’ve done fine with photography without having ever shown these. I probably could’ve done a book with these and with some of the writing and artwork I have a long time ago, but I’ve never been about just promoting myself at all costs without taking others into consideration.

By now, enough time has passed. I’m going through everything. I think I have enough for a book. I have boxes of stuff that just accumulated.

PP: How did all of this work and exposure across three Californian prisons inform the rest of your career?

SR: I always knew I was going to do art. I didn’t know I was going to do photography. I always thought I’d be a painter. The thing that I learned? I learnt that if I couldn’t take any photos, I would collect things!

I took my portfolio everywhere. I got jobs off of the stuff but I never let it out of my hands. You’re the first person to have photographed it, with the exception of the VICE crew who put it in their video. I’m okay with that now. I always guarded it.

I met the guys who were doing COLORS magazine in the late nineties and it definitely influenced them. It influenced their ‘Prison’ issue (June, 2002). I was actually supposed to go to Gaza for COLORS, but the Israelis had bombed the prison right before I was due to leave, so the trip was cancelled. So, I’ve definitely used this stuff to my advantage.

PP: Did you ever give prints to the prisoners?

SR: I’d give them stuff but we kept it low key because I didn’t want any trouble for the program.

PP: Did the guys you taught appreciate that San Quentin had more programs than most prisons?

SR: They liked San Quentin. It’s an old prison. It has a lot of nooks and crannies. There are weird things that go on there that you wouldn’t get in a modern prison.

There was the old hospital built in the 19th century and out of brick. It was structurally unsound after the earthquake and left empty. They’d let certain prisoners go in there at their own risk. The deputy warden or someone in authority allowed one of my students to set up an art studio in there. And he had it for a couple of years! You wouldn’t get that at a lot of other places.

PP: Your photographs form a weird mix.

SR: I’ve always thought it was valid because it was about what I could get and how I could get it.

Soledad prisoners.

PP: Do you think prison systems in the U.S. are racist?

SR: If 11% of California’s population is Black but then at least 36% of the prison population is Black something’s not proportional. That says something about this society. Obviously the system can be racist, but it is also classist. You have a hell of a lot more poor people in prison than you do wealthy people and that’s because wealthy people can afford lawyers.

There weren’t many well educated guys in my classes. They’re obviously smart guys who could do all sorts but they weren’t well educated. I had a blonde white guy who I asked him to read something one time, not even thinking that he didn’t know how to read. It was a horrible thing for him and, of course, for me. I didn’t expect it at all. After that he started taking some of the high school classes and learnt to read.

Prisons are a control thing. [Upon release] if you have people who can’t travel, can’t get housing and can’t vote you can keep a whole population controlled. You can keep a whole population one little step away from being thrown straight back into prison.

PP: So the prison system is failing?

SR: I definitely think some people should be in prison.

There was a child molester who was quite collectible. People like to collect his art. He creeped me out. He made drawings of the kids he had killed from newspaper clippings. I took photographs of them, but I didn’t know that’s what they were until he explained them to me later. He had a scrapbook and the first 20 pages were pictures of Hillary Clinton smiling and then after that it was all these pictures of kids. Innocent pictures – many of them from National Geographic, but when you know what he was about, it’s pretty disturbing.

There’s some fucked up people in the world.

But I also saw, all the time, guys in prison for stupid drugs convictions and I think that is just a waste. The three strikes law was foolish. Keeping someone in prison, which at the time cost something like $30,000 – I’m sure it’s more now – is just a waste of money. You can give people education with that money to help them get better jobs.

I used to go to the visitor center a lot. You’d see the damage being done when families would come up from Los Angeles for the day. Wives would go in and the kids would stay in the guesthouse for the day. The separation of families when they have to travel so far [to where loved ones are imprisoned] is harsh.

Obviously, I believe in education over other things. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have done what I did.

Stefan Ruiz

Ruiz was born in San Francisco, and studied painting and sculpture at the University of California (Santa Cruz) and the Accademia di Belle Arti (Venice, Italy). He took up photography while in West Africa, documenting Islam’s influence on traditional West African art. He taught art at San Quentin State Prison from 1992-1998, and began to work professionally as a photographer in 1994. He has worked editorially for magazines including Colors (for whom he was Creative Director, 2003-04), The New York Times Magazine, L’uomo Vogue, Wallpaper*, The Guardian Weekend, Telegraph Magazine and Rolling Stone. His award winning advertising campaigns include Caterpillar, Camper, Diesel, Air France and Costume National.

© Amy Elkins 269 self-portraits, part of Beyond This Place: 269 Intervals

Last week, I reviewed Photographs Not Taken (ed. Will Steacy, published by Daylight) for Wired.com. It is a book I have enjoyed thoroughly, which may seem a bit perverse as the majority of the tales seem to be about literal death and sullen loss. The other essays are all essentially about metaphorical death – death of an idea; the abandonment of an ideal; fractured and sudden awareness of mortality; or a shattering of photographer-bravado.

Bryan Formhals, many months ago, hollered for more writing by photographers. PNT would be the most recent, stand-out collection of essays to support that call.

PNT features two essays about prison.

Stefan Ruiz talks about his frustration with the limitations on camera during a seven-year stint teaching art at San Quentin State Prison.

“Most of the time […] I was a photographer in a visually amazing place with all these great subjects, and I couldn’t take a picture,” writes Ruiz.

Amy Elkins recounts a visit she and her brother made to see her dad in federal prison in 2005. She ends up describing a thousand or more photographs she didn’t take.

Call it compulsion, call it therapy, her response during the final 9 months of her dad’s imprisonment was to turn the camera on herself. Amy began making self-portraits began in 2006. Her self-portrait series, Beyond This Place: 269 Intervals became a mini internet sensation in 2007, by which time her dad was out but Amy was not out of the habit. Her self-portraits continue in Half Way There and Everybody Knows This is Nowhere.

“All three projects overlap with my father’s story,” says Amy “Half Way There continues as he lived in a re-entry house for 365 days under strict supervision. Everybody Knows This is Nowhere becomes more about re-entering the world and starting over. All in all I’ve shot over 6 years of these portraits.” Amy still photographs herself daily.

You can view the legacy blog posts here and Amy speaks about the relationship between her self-portraiture and family-life briefly toward the end of this conversation with Joerg.

AMY ELKINS’ PHOTOGRAPHS NOT TAKEN

We had been talking here and there. Once a week. Fourteen and a half minutes before hurried goodbyes were exchanged with uncertainty. It was our allotted time to share what we were experiencing. My new chapter in New York. His, in a federal prison, three thousand miles away. My father’s stories were endless. His seventy bunk-mates. Spanish ricocheting off of the concrete walls until it became static, white noise, a flock of birds. The mess hall. The books that had their covers torn off. The Hawaiian friend he made who sang like an angel. The night he woke to flashlights banging along the metal bunks, looking for inmates with blood on their clothes.

The teams that were formed. The chess matches and basketball games. Prison Break on the television in the rec room. The pauses in his voice. We had shared just under fifteen minutes a week for months from across the country. I mostly listened, the imagery leaping to mind, as his words came through the line. These were the things I wanted to make photographs of. By the time I actually had my one and only visit with him while he was in prison, my imagination had grown wild and I was so emotionally charged that I had to place my hands together in order to keep them from shaking, and to hide the amount of cold sweat pooling in them. There were metal detectors, x-ray machines, electronic drug tests, and questionnaires before my brother and I were led into locked waiting rooms, before we were led into a barbed wire walkway, before we were led to the visitors’ area. No cameras, cell phones, keys, wallets, jewelry, hats, purses, food, or gifts were allowed. Just myself, my brother, my father, and a small square yard of short brown grass containing picnic tables, a walkway, and vending machines, wrapped in barbed wire fences, two rows deep. My father, looking aged by stress, wore a tan uniform that seemed to fall all around him like robes. His hair had grown somewhat wild and was whiter than I remembered it. His eyes were youthful and tired.

The photograph was in my head. The moment of panic, of not knowing what to talk about or how to catch up in reality, while families reeled all around us with children and their mothers or grandparents. The vending machine coffees and board games. I longed for this moment to stay preserved, as if it would become more real if I could hold it captive on film.

Or that my story would be more intriguing if I could prove what it looked like. The photograph not taken, a portrait of what we had become, the fear that my family had failed me, the confrontation of unconditional love, a portrait of uncertainty. Instead, I sat with my hands tucked against the worn-out wood of the picnic tables, watching and listening to the sounds of what we were able to be for a moment.

THE SELF

The story runs deep. But how about the images? There’s a touch of naivety in Amy’s self portraits, but no more than any other young artists sussing his or her emotions. The portraits are paired with quotes by her father delivered in those weekly 15 minute calls, a text/image play that adds some depth.

Whatever life these photos have had or will have, I’d like to think they’re ultimately for future generations of her family; mementos of the quirky granny who grew up in the first quarter of the 21st century; the favourite aunt with certainty of narrative but evidence of younger faltering.

After all, we might be miffed if we missed that shot of those things over there, time and time again, but we have no excuse for not recording ourselves. We might hit old age and regret not having the photos to match our memories.

Short-sighted folk may criticise 269 Intervals for its seeming indulgence or vague manipulation; it is strange that images to represent a family temporarily smashed apart by the efficiency of the law are of a pretty las (occasionally in a state of undress) but take a long sighted view and admit you are intrigued by photo-a-day projects. Who hasn’t thought about doing one themselves? … If only you I had the discipline. Between Kessels, Karl Baden, Hugh Crawford, Noah Kalina and Homer Simpson, Amy is in good company.

Amy Elkins was born in Venice Beach, CA, and received her BFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna, Austria; the Carnegie Art Museum in California; and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in Minnesota. Elkins is represented by Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York, where she recently had her second solo exhibition.

I was interested to discover that photographs of San Quentin inmates played a formative role in Stefan Ruiz‘s career. At 4:45mins, Ruiz talks about his position as an art teacher at San Quentin and his compulsion to make portraits.

From a battered Fujifilm box held together with gaffer tape, Ruiz pulls out a wire bound album of prison portraits:

“I really wanted to take pictures of them so I started taking all these photos. I put this whole little notebook together … and I would carry this box [everywhere]. This was before laptops. I used to bring this to Europe all the time and I’d show this. This was what got me jobs.“

Ruiz goes on to explain that he was employed by Caterpillar to imitate the look of those San Quentin portraits. Ruiz’s contact at Caterpillar then moved to Camper and the relationship continued. After Camper Ruiz went to COLORS Magazine as Creative Director (Issues 55 – 60, April 2003 – April 2004). All the while, Ruiz was perfecting his “well-lit” and “polished” style.

Some observers are turned off by the fusion of art/documentary/fashion employed by Ruiz. Common criticism of this multi-genre work is that it can depict poverty as glamorous, violence as eye-candy, and people as consumable props in a visual world obsessed with surface.

The flaw to these dismissive crits is that cinema has been forging this type of imagery for decades; yet, we expect slick augmented reality in the moving image. Ruiz’s use of lights instead of B&W film and the blur of a Leica is hardly an attack on documentary and certainly not on realism (since when has photography ever plausibly claimed a monopoly on realism, anyway?).

Ruiz’s portraits have a solid footing in reality; they are devoid of photojournalist cliche and require participation from the subject. And as far as commercialism is concerned – at least in the case of COLORS – the relationship of money to Ruiz’s aesthetic experiments is acknowledged.

Ruiz likes to “work with the person.” From telenovela actors to hospital patients and clinicians and from rodeo queens to refugees, Ruiz has connected with his subjects through a transparent discussion about what they can achieve together with a device that records and stores their likeness.

The VBS profile of Stefan Ruiz* is a great introduction to his past, present and future trajectory. Highly recommended.

* I apologise for the crude use of screengrabs in this post.

Cast of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest posing for their photograph on location at the Oregon State Hospital, Salem, Oregon, 1974. © MaryEllen Mark.

MARY ELLEN MARK

Mary Ellen Mark first went to Oregon State Hospital (OSH), Salem, OR in 1974 to photograph the cast and set of Milos Forman‘s 1975 adaptation of Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. (Mark often shot on film sets).

During the filming, Mark met the women of Ward 81. She promised to return and after over a year of negotiations with the hospital authorities and families of residents she was allowed to live on Ward 81 with writer Karen Folger for 36 days. American Suburb X has republished Folger’s essay for Mark’s book giving a familiar and surprising account of the routines and dreams of the women on Ward 81.

Mark’s book was a breakthrough. Granted, photographs of Oregon State Hospital existed previously, but Mark’s work was a pioneer intimate portrait of an American group outside of the dream, outside of the reality. LIFE magazine had covered an OSH camping trip before. Oregon Historic Photograph Collections have 14 images of OSH.

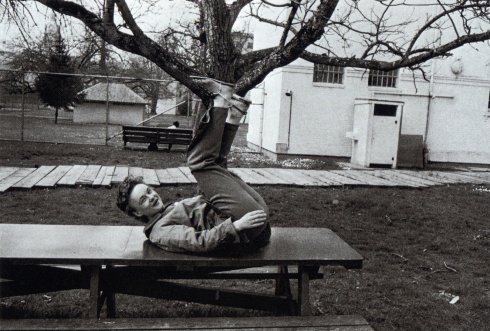

Horsing around. © Marl Ellen Mark, 1974

© Marl Ellen Mark, 1974

Mary Frances Peeking from Tub, 1976. © Mary Ellen Mark.

Mark’s Ward 81 was a personal call to action; she cared deeply about the residents and wanted to use photography to describe their lives. Mark contends in all interviews I have read that the treatment of patients was good and fair.

Prison Photography has touched upon institutions developing an “art” persona overtime through the work of several art photographer, specifically Stateville Prison, Joliet, Illinois. The architectural form of Stateville can be pinned as the common fascination that drew art photographers Gursky, Dubois, Goldberg and Leventi.

Alternatively, the preoccupations at Oregon State Hospital are varied. In some cases, the emergence of a new story to be told and in others an homage to past photographic action at the institution.

DAVID MAISEL

David Maisel‘s Library of Dust is a meditation on the cremains of former OSH patients. Until 2004, the urns were locked in a basement and not public knowledge. The patients died at the hospital between 1883 (the year the facility opened, when it was called the Oregon State Insane Asylum) and the 1970’s; their bodies have remained unclaimed by their families.

Over a period of twenty years the basement in which the urns were locked flooded repeatedly. Studio360 describes well the chemical reactions ongoing between the copper, elements within the ashes and substances afixed by flood water. Maisel’s studies are a “yearbook of the socially dispossessed.”

The Oregonian newspaper won the 2006 Pulitzer for Editorial Writing in its coverage of the forgotten remains and the sad scandal of silence. The story caught the attention of the nation and Maisel’s work toured the country to wide acclaim. Maisel talks about his work here and BLDGBLOG has the best text as entry point to the multiple layers in Library of Dust.

© David Maisel

© David Maisel

The Mental Health Association of Oregon summarises Maisel’s work well:

The tale behind the canisters is indeed deeply disturbing. They hold the remains of 5,121 people who languished in the psychiatric hospital in — many of them for their entire adult lives — for reasons that nowadays might require nothing more than a Zoloft prescription and some couch time. The patients’ conditions listed in hospital records include “worries about sex” and “worries about money” — “things everyone walks around with today,” Maisel says. When these patients died, their relatives either had no money for a burial or no interest in claiming the bodies.

Maisel positions the work within the taboos of “craziness”, “death” but also links Library of Dust to his earlier mineralogical studies. Interestingly, Maisel’s title was first uttered by a custodian of another state institution. Maisel explains:

On my first visit to the hospital, I am escorted to a decaying outbuilding, where a dusty room lined with simple pine shelves is lined three-deep with thousands of copper canisters.

Prisoners from the local penitentiary are brought in to clean the adjacent hallway, crematorium, and autopsy room. A young male prisoner in a blue uniform, with his feet planted firmly outside the doorway, leans his upper body into the room, scans the cremated remains, and whispers in a low tone, “The library of dust.” The title and thematic structure of the project result from this encounter.

While on site, Maisel also made some interior studies of the decaying fabric of the building. The series is Asylum. OSH was shuttered in 2005 and demolition began in 2008. A new facility is slated for completion in 2012.

Asylum 2. Doctor’s Office, Ward 66, Abandoned portion of J Building. © David Maisel.

Asylum 3. © David Maisel

Asylum 7. Tubs, Ward 7, Abandoned portion of J Building. © David Maisel

Maisel’s studies of the interior are less complex or politicised as the poetics of Library of Dust. Nevertheless, bare these images in mind as you read on.

CHRISTOPHER PAYNE

Between 2002 and 2008, Chrsitopher Payne took on the largest photographic survey to date of America’s decaying psychiatric hospitals. For Asylum, Payne visited scores of old facilities and OSH was among them.

Interestingly Payne, photographed the storage room of cremains but didn’t extrapolate the stories into a memorial of politics as Maisel expertly did. And once, again the steep sided tiled bath tubs make a reappearance.

Oliver Sacks wrote the essay for Payne’s book. It is a ranging historical narrative of palatial institutions that could provide the best and the worst of care, but in most cases rarely prepared the patient for release back into society, “most residents were long-term.” The essay is accompanied by some wonderful historic postcards and generally Sacks tries to push us away from a narrative of “snake pits” and “hells of chaos” when thinking of psychiatric hospitals.

On Payne’s work, Sacks’ description is exactly how it appears, “[Payne’s photographs] pay tribute to a sort of public architecture that no longer exists. They focus both on the monumental and the mundane, the grand facades and the peeling paint.”

© Christopher Payne

© Christopher Payne

Peeling paint and broken down fixtures is a preoccupation of many a photographer. Architectural enthusiasts, disaster journalists and fine art photogs have all conspired to bring us the genre of “ruin porn” which continues to baffle and frustrate as much as it engages (but that discussion is for another time).

BILL DIODATO

This inquiry began when Bill Diodato contacted me with news of his book release. c/o Ward 81 is a conscious revisit to OSH; a closing of the circle of photographic practice put into motion by Mary Ellen Mark 30 years previous. Indeed, Mark provides the foreword:

‘It’s painful for me to look at these pictures. They evoke feelings of life and death. I can hear the sounds of women running through hallways and someone shouting, “Meds, meds, come and get your meds.” I can hear the crying of a woman being locked down in restraints. I can hear the music of the jukebox at the once-a-week dance with the women of Ward 81 and the men of Wards 82 and 83. Bill’s book brings me back to the haunted cell in which I slept in a deserted ward right next to Ward 81. I swear I heard people walking above me all night. This was so puzzling because the floor was not occupied. Bill’s images confirm the feeling that I always had—that Ward 81 was and still is inhabited by many ghosts. ‘ (Source)

Diodato states that this book is about the “demise of institutional services’ and it’s effect on women.” When Diodato visited both he and Warden Marvin Fickle knew he would be the last person to document the infamous closed-off Ward 81.

c/o Ward 81 is more focused than Payne’s one stop of many on his tour US psychiatric hospitals and it is more intentional than Maisel’s context-giving shots that rightly or wrongly have formed the backdrop to Library of Dust. Diodato is paying homage to the cultural impact of golden-age documentary photography as much as the site itself.

“The physical crumbling and decaying cells, represent the end of old, corrupt, poorly-run asylums and bring about a sense of closure for the women of Ward 81,” explained Diodato by email. But I can’t help think that’s a superimposition of idea upon the images. Mark’s refuted allegations poor treatment of patients in some interviews, yet talks of “hauntings” in the book intro quoted above. OSH did become known for substandard mental health care provision, but was it a constant of the institution, over all its years?

In addition to being a requiem to the occupants, residents and survivors of OSH, Diodato’s images are a requiem to public awareness.

The silenced and invisible lives of the population within OSH and similar facilities is a shameful past. Diodato’s images represent for me a breakdown in social responsibility for one another. How else can we explain OSH’s unclaimed remains for over 5,000 individuals? Families wrote their relatives out of family history just as the old asylums of the 19th and 20th century allowed the public to erase patients from the social fabric.

© Bill Diodato

© Bill Diodato

© Bill Diodato

Oregon State Hospital was demolished in 2008. A new era and a new regime of treatment and control is to be established upon completion of the new proposed complex (below). What – if any – will be the photographer’s interaction with the new $458 million complex and its residents?

FURTHER READING

“Mary Ellen Mark – 25 Years” (1990) Pt. I and “Mary Ellen Mark – 25 Years” (1990) Pt. II

Interview: Mary Ellen Mark on Photography (Oregonian)

Interview: The Unfiltered Lens of Mary Ellen Mark