You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Soledad’ tag.

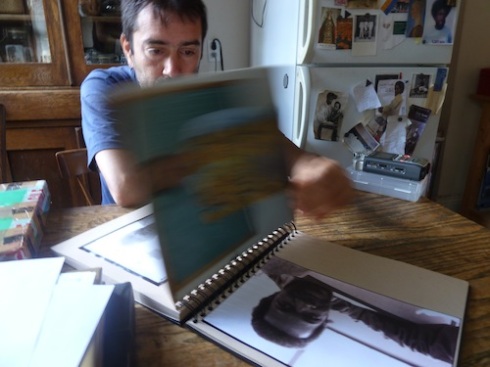

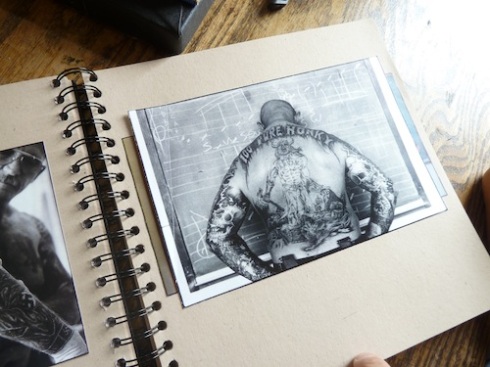

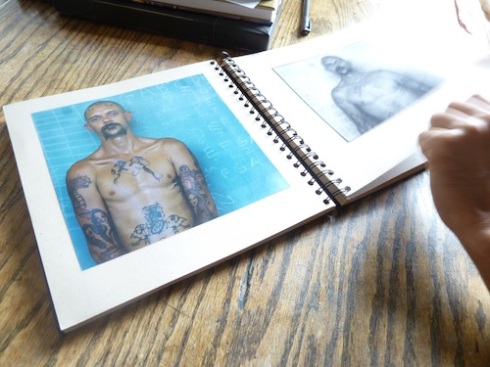

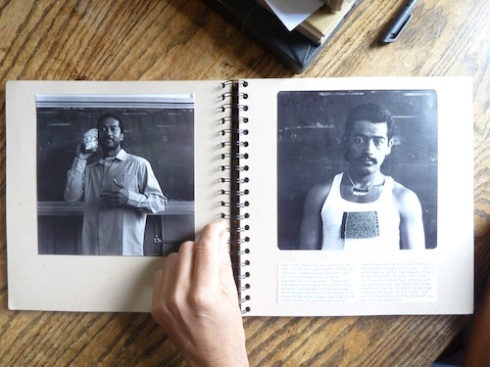

In the kitchen of his Brooklyn home, Ruiz flicks through his “portfolio” of prison images.

Stefan Ruiz has made photographs inside San Quentin State Prison, Soledad Prison and the notorious maximum-security Pelican Bay State Prison. His photography from within California’s prisons was not accomplished by conventional methods; at no time was Ruiz on press assignment; making documentary work or running a photography workshop.

Ruiz worked for seven years as an art instructor at San Quentin, during which time he regularly made photographic records of individual artworks. He took some portraits of his students on the side. He got inside Pelican Bay as a court-appointed photographer making photographs for use as trial evidence.

It’s a bit of a family affair. Ruiz’s mother, a professor at UC Santa Cruz, was teaching art at Soledad. Ruiz had studied Islamic art in West Africa and went to deliver a talk to Muslim prisoners at Soledad. He delivered the same lecture later at San Quentin, at which time he was introduced to the art program coordinated by the William James Association.

Ruiz’s father is a criminal defense attorney, who in the mid nineties represented a prisoner at Pelican Bay. Ruiz was the case-for-defense’s chosen photographer, documenting conditions the of client’s confinement.

In addition to his photography, Ruiz made sketches, collected his students’ artwork, and acquired objects typical of prison culture. When he showed me a photograph of a DIY prison tattoo gun, I asked, “Is that something an inmate showed you or is it something that had been confiscated?”

“It’s something I have,” Ruiz replied.

The first photos Ruiz made inside were portraits of Soledad prison-artists holding their work. He took six rolls of film. At the age of 23, Ruiz began teaching art at San Quentin. One of his students had been a student of his mother’s at Soledad years prior. Prison-art hangs in Ruiz’ house and he has collected mug-shots for years.

In the mid-nineties, Ruiz cobbled together a photo “notebook” of his pictures of people and vernacular art. He keeps it in an old Fujifilm box bound with packing tape. “I used to take this with me everywhere; it was my portfolio.”

From humble and organic beginnings, Ruiz is now one of the most respected portrait and editorial photographers in America. Until recently he had never spoken about his experiences in California’s prisons. We sat down in his kitchen to unpack his memories and his homebrew portfolio.

Q&A

PP: Your mother introduced you to prison-life?

SR: My mother organized exhibitions of the prisoners’ artwork. I helped out by taking photos of the artwork and making slides of their work. Some of that would go to William James Association to help them appeal for funding or for entry into competitions. That’s how I got cameras into the prison at first. Whenever I took a camera into a prison it was legal, and it was generally to photograph some type of art object.

PP: Of your prison work, it is your portraits that are known, however minimally, in the public sphere. I wasn’t aware of them until you were featured on VICE TV’s Picture Perfect.

SR: There are more photographs than just portraits. I taught at San Quentin for so long, and my boss had such a good relationship with the officials that gave access, that we were allowed to do quite a few things.

The first portraits I did were of the guys in my mother’s art class at Soledad who were to be involved in an exhibition. The way we were allowed to make portraits was to say, since they couldn’t make it to their show, their portrait would.

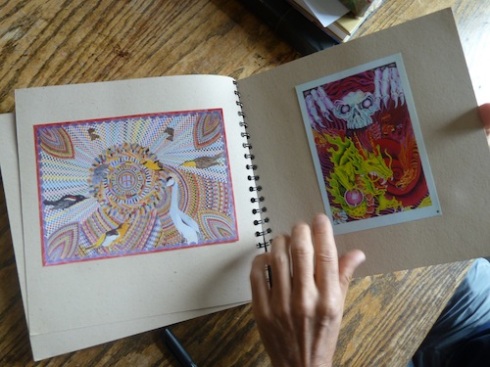

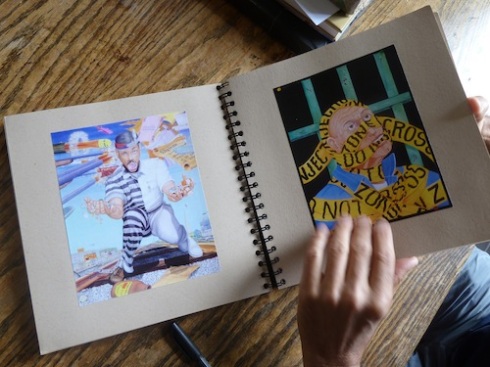

Prisoner art

Prisoner art

PP: Describe the art program.

SR: My boss played bass and the main emphasis of the art class was music but there were two visual artists who taught and I was one. The other was Patrick Maloney, who I guess is still teaching there. Patrick would also teach on Death Row. Sometimes, I would fill for him or accompany him on Death Row.

PP: How did you find working on death row?

SR: You move along the tiers and talk [through bars] to students individually, whereas on the mainline they come out their cells and they come to you.

There are two different sections of death row. In the first, there are a couple of tiers of just death row inmates. You’d need the key to get on the tier, and then you’d go from cell to cell, depending on who was part of the program. There might be three or four guys on a single tier. They had to buy their own supplies but through William James we also gave them supplies. Mostly you’d spend time talking to them. Each day, they might get half an hour outside their cell.

In the other section, the prisoners could leave their cells and go to a common space with some tables. There you could have two or three people in the class. That seemed like a better place to be on death row. The tiers are quite dark. Five tiers. And the other side is just open. One of our students was executed. He had killed a shopkeeper and his wife robbing a store in Los Angeles. He was a good student.

PP: Your mother was a professor at Santa Cruz, teaching art classes at Soledad. Those two institutions have a long and significant relationship going back to the protests and counter culture of the late sixties, Black Pantherism, and the book Soledad Prison: University of the Poor (1975) which was a collaboration between UCSC students and prisoners at Soledad.

PP: You gave a talk to Muslim students at Soledad, then to Muslim students at San Quentin and then you began in the art program. That trajectory explains your path but not your motivations. Why did you decide that leading arts education with prisoners was something you wanted to commit to multiple times a week, and eventually over seven years.

SR: Because it is interesting. I have to say; I think I learnt more from them than they learnt from me.

My father is a lawyer in criminal defense and labor law. His family is Mexican and he’s pretty liberal, so I grew up with that element too. Teaching art in prison was an activity that brought together both sides of my family.

PP: A context in which prison teaching is not a radical act?

SR: My mother was more or less a hippie. My father couldn’t really be one, he was just trying to assimilate, but he was definitely liberal. Growing up in Northern California at that time it was more of a norm than not to be on the left. To do things such as teaching in prison was not considered wild. There was no whole movement about victims’ rights as there is now.

Fair enough. There’s a lot of bad people in prison and some people who deserve to be there but …

When I was a kid, my parents were involved in a free school. We grew up in the country growing organic food. That was way before the trends of today. We composted everything; we weren’t allowed to have plastic bags for lunch. We had wax paper and baked our own bread.

The thing is the prison was interesting to me. At San Quentin they allowed me to take keys. The room where I taught art used to be a laundry room. There was a bunch of people that got murdered there, I guess in the seventies or eighties so they closed it down and eventually opened it up as an art room.

There was never a guard in our room. It was two levels but we would teach on the lower level. The closest guard was in what we would call the max-shack – a checkpoint, probably about 30 yards outside the door. I was really young when I was teaching there and a lot of the guys were way bigger than me. It was interesting to learn how to navigate that. There were anywhere from 5 to 15 people in my class. 15 would be a little bit hectic. Often we’d just get someone from the yard and have him come and sit. Students who wanted could draw him, and if not, they could work on other projects.

PP: Were any of them reluctant to paint or draw other prisoners? My experience teaching art in prison was that collectively they decided it was “suspect”, for want of a better term, to spend the time and energy painting another prisoner. Most of them made portraits of wives, girlfriends or children in a devotional way so to paint another prisoner made no sense to them and was in fact considered strange. They felt other prisoners would misconstrue it as a gesture of adoration or romantic attraction to the subject and that is something most guys wanted to avoid.

SR: No, most of them were into it. They didn’t have to do it but one thing is that since cameras aren’t allowed in prison you can make money if you can draw well, by drawing portraits, usually by copying photographs of prisoners’ family members. If you’re good you can make money. It’s like a throwback to an era before the camera; I can draw fairly realistically and that kind of saved me when I was in there because …

PP: … there’s a lot of respect attached to that ability.

SR: Yes. They’d give me a lot of shit and then we’d start drawing and it’d be fine. I generally had quite a few lifers in the class, because they are the ones who are more serious – eventually they decide to try and use their time. Young guys, who were only in for a little while, might joke around. The older guys kept the class in order.

PP: At what other times did you use your camera?

SR: There’s some really famous murals in San Quentin. I photographed them all.

PP: Was that the San Quentin administration that asked you to do that, or was it William James or was it self-initiated?

SR: My boss, Aida de Arteaga and I, decided it was a good thing to do. There are four dining halls. It used to be one huge one but it was divided because they were worried about riots. Three walls. Six sides on which the murals were painted. A Mexican-American inmate who had been busted, I think, for selling heroin painted the murals in the fifties. When I was still there, he came back to San Quentin, for the first time since his incarceration.

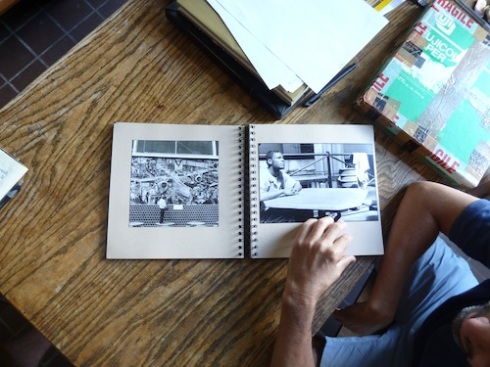

Photos from the San Quentin Prison dining halls. One of Ruiz’ students stands in front of the famous murals.

PP: In Photographs Not Taken you close with a bittersweet statement in which you said while you managed to take photos you still thought about the ones you weren’t allowed to take in such a “visually rich environment.” Did the staff or inmates think of their environment as visually rich?

SR: Obviously, most of the prisoners wanted to be out of there. I’m sure quite a few of the guards would like to have taken photos. Some did. Various guards had cameras for different reasons.

PP: What reasons?

SR: To photograph events. I photographed some of those too. We had concerts in the main yard, which is pretty impressive at San Quentin when you are down there with all the inmates. One time we had Ice Cube come in. On that billing, they had a white performer, a Hispanic performer and Ice Cube was the black performer. The administration has to play it like that.

Ice Cube performed in one of the dining halls and that was pretty crazy. You could see the guards were quite nervous. Some of the inmates were getting fired up. I don’t think they had another concert like that.

The prison liked the art program quite a lot and there were some guards who were supportive of our classes. Guards will either make things easy or hard for you. Basically, I think we were lucky for a lot of the time; we had people who were kind, trusted us, let us do more.

The thing about being there for so long is that you got know people fairly well. Especially being in a classroom when you’re with students for three or four hours at a time just drawing and talking. The thing that struck me was that I had a few guys who were lifers and had been in for 20 to 25 years; that’s a pretty crazy concept, especially now given all the changes that have happened, specifically with technology. I am sure – unless they were using them with their jobs within the prison – none of them had used a computer.

PP: Did you ever think there was an opportunity for you to do a photography workshop?

SR: The administration didn’t want us to do that at all. Even toward the end, they started to question me taking drawings out of the prison because many of them were realistic to the point that you could identify people in the drawings!

PP: What did the administration think of the portraits you did manage to take?

SR: They didn’t see most of them. They had signed-off on me doing photography, but they didn’t necessarily see the photographs. We got releases form the guys too. Guards might follow me round for a while, but I can take photos for days and bore the shit out of anyone. [Laughs].

I’ve probably got one of the best [records of the murals]. They were done on 4×5. I even did some on 8×10. I got in there at different times. Once, I’d used a Linhof 617 lens and camera on a commercial job, then I got access and so I used it in the prison.

PP: Did I hear that the Smithsonian has come to some sort of agreement, where by if and when San Quentin is demolished, they’ll remove and preserve the murals?

SR: They’ve been saying that for years, but I don’t know. The murals depict the history of California. The prisoners love the cable-car because the perspective is right so as you walk around it works.

“This guy before he took his shirt off warned me that his tattoos were considered some of the most racist in the prison. There’s the SS helmet skeletons.” Tattoos read ‘100% Honky’ and ‘Aryan’.

Ruiz used a chalkboard as a backdrop, “I liked the color and I liked the reference to education.” Some prisoners shaved their heads ready for the shoot. “They knew I was bringing in the camera so they prepared,” says Ruiz.

PP: It seems like the prison administration’s policy toward camera use was ad hoc?

SR: I photographed in Pelican Bay and Tehachapi, but I actually did that through a court order. My father was representing a prisoner who the CDC said was one of the heads of the Northern Mexican mafia and that he was ordering murders from his cell in Pelican Bay.

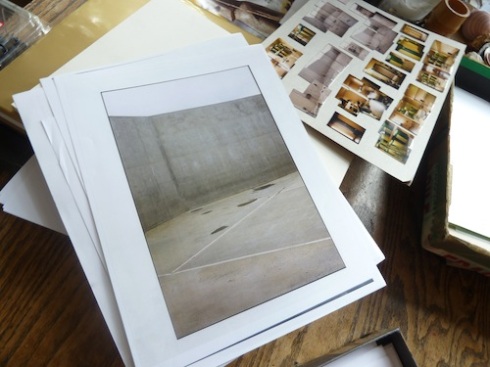

In Pelican Bay I had to use the prison’s cameras; they wouldn’t let me take in any of my own equipment, except film. This was 1995. They held on to the film, processed it, and then gave everything to me, negatives and all. The images are a bit … the lenses were a bit crazy. It’s not what I would’ve used but it was fine.

In Tehachapi, I got to use one camera and one lens. Both were mine.

PP: What was your brief for the court order?

SR: I had to photograph the cells and so the reason these photos are joined together is that they only allowed me the one lens.

Ruiz photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison, CA made in 1995 for use as court evidence.

4/4/95, Pelican Bay – “The defendant was in one of these cells.”

“Pelican Bay is obviously freaky.”

“This is the yard at Tehachapi. This is a common area, these are the cells.”

PP: It’s because of the connection through your father that you got the court ordered gig?

SR: As a defense attorney, he was allowed to bring in his own photographer. As an art teacher, I’d actually spent more time inside of prisons than my father had. Normally, he would only go to a visiting room where he would talk to his client. Whereas, I used to go on tiers, I went in cells. There were times at San Quentin when I was totally unsupervised and there were times it felt a little freaky.

PP: Were any limits placed or pre-agreements made by the courts on your photographs to limit their circulation, or are they just yours?

SR: They’re just mine.

PP: Is there a reason why you’ve not shared them widely yet?

SR: There are some that I considered might be a bit sensitive and I didn’t want to get my boss into trouble in any way. The photographs from Pelican Bay and Tehachapi are fine. The ones from San Quentin; she’d help me get the camera in. We had an understanding. I wasn’t going to screw her over.

It’s more important for me to be cool with her than it is to profit from the photos. I’ve done fine with photography without having ever shown these. I probably could’ve done a book with these and with some of the writing and artwork I have a long time ago, but I’ve never been about just promoting myself at all costs without taking others into consideration.

By now, enough time has passed. I’m going through everything. I think I have enough for a book. I have boxes of stuff that just accumulated.

PP: How did all of this work and exposure across three Californian prisons inform the rest of your career?

SR: I always knew I was going to do art. I didn’t know I was going to do photography. I always thought I’d be a painter. The thing that I learned? I learnt that if I couldn’t take any photos, I would collect things!

I took my portfolio everywhere. I got jobs off of the stuff but I never let it out of my hands. You’re the first person to have photographed it, with the exception of the VICE crew who put it in their video. I’m okay with that now. I always guarded it.

I met the guys who were doing COLORS magazine in the late nineties and it definitely influenced them. It influenced their ‘Prison’ issue (June, 2002). I was actually supposed to go to Gaza for COLORS, but the Israelis had bombed the prison right before I was due to leave, so the trip was cancelled. So, I’ve definitely used this stuff to my advantage.

PP: Did you ever give prints to the prisoners?

SR: I’d give them stuff but we kept it low key because I didn’t want any trouble for the program.

PP: Did the guys you taught appreciate that San Quentin had more programs than most prisons?

SR: They liked San Quentin. It’s an old prison. It has a lot of nooks and crannies. There are weird things that go on there that you wouldn’t get in a modern prison.

There was the old hospital built in the 19th century and out of brick. It was structurally unsound after the earthquake and left empty. They’d let certain prisoners go in there at their own risk. The deputy warden or someone in authority allowed one of my students to set up an art studio in there. And he had it for a couple of years! You wouldn’t get that at a lot of other places.

PP: Your photographs form a weird mix.

SR: I’ve always thought it was valid because it was about what I could get and how I could get it.

Soledad prisoners.

PP: Do you think prison systems in the U.S. are racist?

SR: If 11% of California’s population is Black but then at least 36% of the prison population is Black something’s not proportional. That says something about this society. Obviously the system can be racist, but it is also classist. You have a hell of a lot more poor people in prison than you do wealthy people and that’s because wealthy people can afford lawyers.

There weren’t many well educated guys in my classes. They’re obviously smart guys who could do all sorts but they weren’t well educated. I had a blonde white guy who I asked him to read something one time, not even thinking that he didn’t know how to read. It was a horrible thing for him and, of course, for me. I didn’t expect it at all. After that he started taking some of the high school classes and learnt to read.

Prisons are a control thing. [Upon release] if you have people who can’t travel, can’t get housing and can’t vote you can keep a whole population controlled. You can keep a whole population one little step away from being thrown straight back into prison.

PP: So the prison system is failing?

SR: I definitely think some people should be in prison.

There was a child molester who was quite collectible. People like to collect his art. He creeped me out. He made drawings of the kids he had killed from newspaper clippings. I took photographs of them, but I didn’t know that’s what they were until he explained them to me later. He had a scrapbook and the first 20 pages were pictures of Hillary Clinton smiling and then after that it was all these pictures of kids. Innocent pictures – many of them from National Geographic, but when you know what he was about, it’s pretty disturbing.

There’s some fucked up people in the world.

But I also saw, all the time, guys in prison for stupid drugs convictions and I think that is just a waste. The three strikes law was foolish. Keeping someone in prison, which at the time cost something like $30,000 – I’m sure it’s more now – is just a waste of money. You can give people education with that money to help them get better jobs.

I used to go to the visitor center a lot. You’d see the damage being done when families would come up from Los Angeles for the day. Wives would go in and the kids would stay in the guesthouse for the day. The separation of families when they have to travel so far [to where loved ones are imprisoned] is harsh.

Obviously, I believe in education over other things. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have done what I did.

Stefan Ruiz

Ruiz was born in San Francisco, and studied painting and sculpture at the University of California (Santa Cruz) and the Accademia di Belle Arti (Venice, Italy). He took up photography while in West Africa, documenting Islam’s influence on traditional West African art. He taught art at San Quentin State Prison from 1992-1998, and began to work professionally as a photographer in 1994. He has worked editorially for magazines including Colors (for whom he was Creative Director, 2003-04), The New York Times Magazine, L’uomo Vogue, Wallpaper*, The Guardian Weekend, Telegraph Magazine and Rolling Stone. His award winning advertising campaigns include Caterpillar, Camper, Diesel, Air France and Costume National.