You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prisons’ tag.

“There is beauty and there is truth and most truth in this present world is ugly.”

Momena Jalil

“In the central jail of the capital Dhaka, it is unbearable to live there. It is impossible to document it, cameras are not allowed inside.”

Momena Jalil

The prisoners sit on the floor of the common cell; this special newly opened women prison has much space. But in the central jail in the capital Dhaka this same amount of space is packed with women and their children.

I received an email yesterday from Diederik Meijer, editor of The Black Snapper, an online magazine that presents each day the work of a new photographer. The works are selected by guest curators and grouped under a weekly (geographical) theme.

I was happy Meijer contacted me.

This week, The Black Snapper is focusing on photographers from Bangladesh. Following Andrew Biraj, they’ve featured Momena Jalil a photographer whose work I’ve pointed out before. Prison Photography and The Black Snapper share admiration for the Bangladesh photographic community and its numerous talents putting work out internationally.

Momena Jalil’s project is obscured however; her photographs are only half the story of sorry conditions in Bangladesh’s prisons.

These are the images she was allowed to take … and this is a newly operating jail. She was not granted access to the older sites of incarceration. The scenario is quite bizarre. Jalil speculates that, in 2007, this prison was hastily finished so as to house two prominent female political leaders. Not all the buildings, such as the male or juvenile blocks, in the compound were completed or in use at the time of Jalil’s visit. The prison was opened amidst a choreographed national media campaign.

Jalil refers to the women in their prison provided white shari with blue stripes as “angels without wings”. Jalil suggests that the crimes accused and evidence gathered are neither properly articulated or adequately qualified. Who are we to judge these women when the system that cages them exposes itself to grave question?

Take the time to read Jalil‘s involved and emotive response to the womens prison and be sure to follow the high standard of work presented by The Black Snapper.

The eyes of Salma tell more than we can read or understand, perhaps there is complaint, plea, anguish, misplaced trust or betrayal? It is fact a she hides her lips but she kept her eyes open. It is sad we are illiterate to the language of eyes.

Photo & Captions: Momena Jalil

Cornell Capa, to some extent, lived in the shadow of his older brother Robert. I guess, it is easy for complacent men to adore the still and fallen martyr than to keep apace with a passionate and piqued practitioner. Cornell’s and Robert’s legends are one; Cornell ceaselessly fought his brother’s corner authenticity debate surrounding The Falling Soldier.

Cornell’s indebtedness to his brother was fateful and self-imposed:

Disappointingly, it is only in extended surveys of Cornell Capa’s career that mention of his fifties photojournalism in Central and Southern America arises. Otherwise, Cornell is celebrated for his political journalism and particularly his campaign coverage of Adlai E. Stevenson, Jack and Bobby Kennedy. Cornell’s photographs from Latin America are often neglected, even demoted.

The Kennedys were the foci of American progressive attitudes, and so, in the sixties, Cornell documented the concerned politician. Cornell was (not in a negative way) passive and the sixties were not formative. It was in the fifties that he actively worked to define the persona, the ideal: ‘The Concerned Photographer’.

Cornell’s work in Latin America:

In 1956, Cornell was in Nicaragua reporting on the assassination of President Anastasio Somoza García. Somoza was shot by a young Nicaraguan poet; the murder only disrupting slightly the Somoza dynasty that lasted until the revolution of 1979 (that’s where Susan Meiselas picks up).

In the aftermath of the assassination over 1,000 “dissidents” were rounded up. The murder was used as an excuse and means to suppress many, despite the act being that of one man.

I have no knowledge of what happened to these men after Cornell photographed them and I am sure you haven’t the patience for speculative-art-historio-speak.

I do wonder … if having witnessed revolution, early democracies, military juntas, coups, communism, social movements, grand narratives and oppression in various forms, if Cornell picked his subjects with discernment back in the United States.

As early as 1954 Cornell was working on a story for Life about the education of developmentally disabled children and young adults. Up and to that point in time, the subject had been regarded by most American magazines as taboo. The feature was a breakthrough.

In 1966, in memorial to his brother, Robert, and out of his “professed growing anxiety about the diminishing relevance of photojournalism in light of the increasing presence of film footage on television news” Cornell founded the Fund for Concerned Photography. In 1974, this ideal found a bricks and mortar home on 5th Ave & 94th Street in New York: The International Center for Photography.

This institutional limbo that eventually gave rise to one of the world’s most important photography organisations was not a quiet period for Cornell. In 1972, he was commissioned to Attica, NY, to document visually the conditions of the prison. Capa presented his evidence to the McKay report (PDF, Part 1, pages 8-14) the body investigating the cause of the unrest. Cornell narrates his personal observations while showing his photographs to the commission.

At a time when, the photojournalist community seems to have crises of confidence and purpose at an alarming rate, it would be wise to embrace his spirit in full recognition his slow accumulation of remarkable accomplishments.

Rest In Peace, Cornell.

PHOTO CREDITS.

Robert F. Kennedy campaigning in Elmira, New York, September 1964. Accession#: CI.9685

New York City. 1960. Senator John F. KENNEDY and his wife, Jackie, campaigning for the presidency. NYC19480 (CAC1960014 W00020/XX). Copyright Cornell Capa C/Magnum Photos

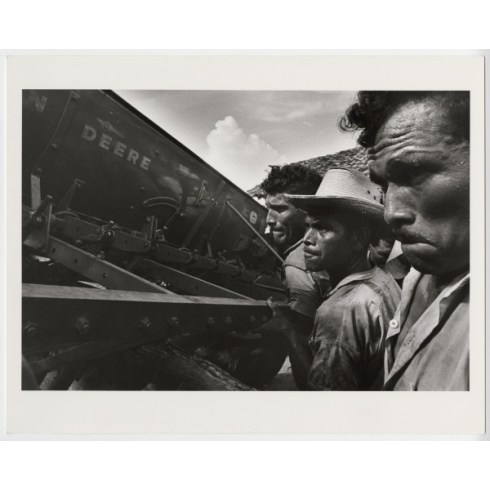

Three men pushing John Deere machine, Honduras, 1970-73. Accession#: CI.3746

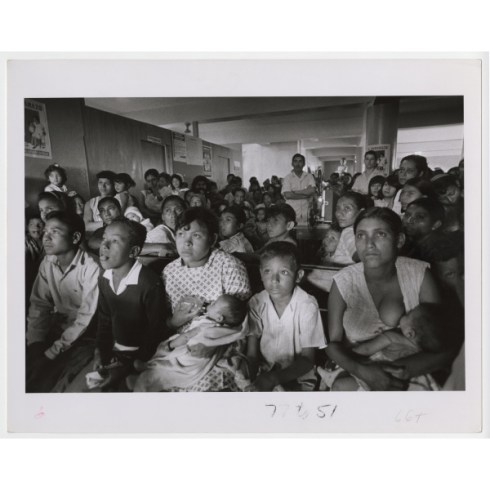

Watching family planning instructional film at Las Crucitas clinic, Tegucigalpa, Honduras], 1970-73. Accession#: CI.8544

Political dissidents arrested after the assassination of Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Somoza, Managua, Nicaragua, September 1956. The LIFE Magazine Collection. Accession#: 2009.20.13

NICARAGUA. Managua. 1956. Some of the one thousand political dissidents who were arrested after the assassination of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza. NYC19539 (CAC1956012 W00004/09). Copyright Cornell Capa/Magnum Photos

Prisoners escorted from one area to another, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, March 1972 (printed 2008). Accession#: CI.9693

Two men walking around prison courtyard, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, March 1972. Accession#: CI.9689

Inmates playing chess from prison cells, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, March 1972. Accession#: CI.9688

Man on scooter carrying coffin, northeastern Brazil, 1962. Accession#: CI.8921

All photos courtesy of The Robert Capa and Cornell Capa Archive, Promised Gift of Cornell Capa, International Center of Photography. (Except for ‘The Concerned Photographer’ book cover; the Jack Kennedy photograph; & the second Nicaragua prison photograph.)

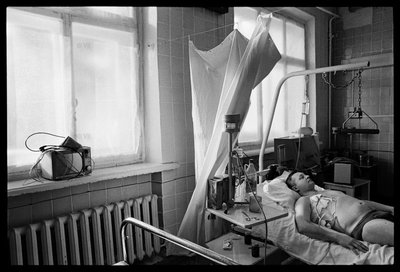

A TB patient at Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #3. Photograph and caption © James Nachtwey/VII.

“Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty and stress“.

Merrill Goozner, The Center for Science in the Public Interest.

“Sixty percent of all new cases of tuberculosis have resulted from the rapid growth of the post-Communist prison archipelago”.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Aug. 26th, 2008

Tuberculosis (TB) was under relative control in the former USSR. Soviets had lifestyles, nourishment and conditions of living that kept disease at bay. When communism fell, so did a civil order in many areas. The phalanx of activity that filled the vacuum involved new systems, new relationships, new businesses and new criminal opportunities.

The prisons filled in a society that needed to organize itself before it could organize it’s transgressors. The prison population swelled to 1.1 million (it is now down to little over 700,000). Post-communist prisons held malnourished, crowded populations with weak immune systems; they have been described as ‘Tuberculosis incubators‘.

Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. TB patient/prisoner gets a chest x-ray. Treatment is supervised by Partners in Health in partnership with the government TB program. James Nachtwey/VII

TB is best treated with various labour intensive methods known under the umbrella-term Directly Observed Therapys (DOTs). Due to TB’s many different strains – each with different drug resistancies – case by case treatments differ according to patient reactions to drugs. At the least, a patient must be observed and his/her drug regime modified over a 6 month period. For Multi-Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) the treatment can take as long as two years. And, MDR-TB & XDR-TB are increasingly common among prison and civilian populations of Tomsk and other Siberian urban centers. Unfortunately, closely monitored drug regimes are improbable in over-stretched and poorly funded state systems.

It wasn’t always so dire. The former Soviet provided a regular supply of drugs to abate disease amongst its prison population, but those supplies were interrupted in the fall of Communism – sporadic and incomplete treatments gave rise to multiple resistant strains of tuberculosis. To compound this the side effects of drugs were enough to discourage patients, and rarely, if ever, did courses of treatment go with a prisoner into his community following release.

TB patients smoke cigarettes in the smoking room of Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #1. James Nachtwey/VII

James Nachtwey‘s mega-promoted TED prize crusade addresses the spread of Extremely Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB), its mutant forms and human tolls. This excellent Guardian article notes Nachtwey has photographed the epidemic worldwide, from Siberian prisons to Cambodian clinics.

A prisoner who was convicted of murder was moved from prison to the TB ward of Battambang Provincial Hospital, Battambang, Cambodia when he was diagnosed with TB. He is coinfected with AIDS. James Nachtwey

Nachtwey stands with Sebastião Salgado in the “super-photographer” stakes. They both make the ugly beautiful.

Both Nachtwey and Salgado have inspired others to action and both believe firmly in the power of photography to change existences … even in a time when such sentiment is derided as old-fashioned, false idealism.

But, despite the odds, Nachtwey has succeeded in forcing his work into the conscience of millions. For some his work is an inspiration for social justice; but for others his work is a sub-conscious default to guilt, despondency and powerlessness to help others less fortunate.

James Nachtwey puts human faces to global suffering. And we are outraged. Or we feel we should be outraged.

I think Nachtwey wants us to believe in ourselves as agents of change. Nachtwey deliberately chose Tuberculosis – because while the situation is critical, it is not terminal and TB is theoretically entirely curable. Beating TB on a global scale is dependent on the behaviours of individuals and their communities.

Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. A prisoner proves to a nurse that he has swallowed his daily oral TB medication. The prisoners receive treatment through metal bars in order to give security to the nurses. Treatment is supervised by Partners in Health in partnership with the government TB program. © James Nachtwey/VII.

Nachtwey’s work extended beyond the prison walls in Tomsk and went into the public clinics (some images included here show those facilities); TB is no respecter of human walls or demarcations. Regional, economic poverty will spike rates of TB.

A TB patient has excess fluid drained from his chest a Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #1. James Nachtwey/VII

The worst thing we could do here would be to think that TB is a disease of other nations and other peoples. In Pathologies of Power (2004), Paul Farmer wrote about the New York prison system’s huge Tuberculosis epidemic of the mid-nineties, “By some estimate, it cost $1 billion to bring under control”. The strains that arose in the NYDoC have been directly related to the resistant strains of the former Soviet Union. Tuberculosis is latent within one third of the world’s population. Tuberculosis needs only the conditions for its growth.

Paul Farmer, of Mountains Beyond Mountains fame has taken the lead on combating TB, as well as other infectious diseases, amongst the world’s poorest populations. He worked with Partners in Health partly funded by a Soros Grant to “develop demonstration tuberculosis control projects which could become a model for replication throughout Russia.”

A nurse prepares a daily injection for TB patients at Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #3. James Nachtwey/VII

Prison Photography blog has focused twice previously on photographers’ responses to the USSR and its aftermath – the Gulag and the new prisons that arose. While Anna Shteynshleyger and Yana Payusova are working with very different issues, regions and populations they – along with Nachtwey’s work – remind us of the severe problems facing parts of modern Russian society. Unfortunately, and certainly in the case of Tuberculosis, these problems exist in other nations also. Nachtwey focused on TB because it was not – despite being a global problem – on the radar of most people. That sounds like something I’d say about prisons and prisoners’ rights.

Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. A patient/prisoner receives a daily medical injection. The prisoners receive treatment through metal bars in order to give security to the nurses. Treatment is supervised by Partners in Health in partnership with the government TB program. James Nachtwey/VII

For more information on XDR-TB read the Action – Advocacy to Stop TB Internationally website, and the Center for Disease Control & Prevention website. For the most accessible and recent article, read Merrill Goozner’s 2008 Scientific American article about Russian Tuberculosis strains which also includes a audio segment with a clear explanation of the situation.

A TB patient/prisoner receives his daily oral medication at Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. © James Nachtwey/VII.

James Nachtwey built his reputation as a combat photographer.

He was always reluctant to be the focus of media attention but after 5 Capa Gold Medals for War Photography he couldn’t escape the curiosity of Christian Frei who made the extraordinary film War Photographer. Nachtwey comes across as an articulate, self-isolated journalist-force devoted to his craft and courteously distant to others; here is a clip.

Nachtwey has done interviews here, here and here. Read an interview about his 9/11 pictures, and associated videos on Digital Journalist. The images were published in TIME.

He worked in Rwanda for his book Inferno.

View his TED Prize acceptance speech and the consequent October 2008 launch of his XDR-TB project and Flickr pool.

Obama Stencil. By Christopher V. Smith. Source http://www.flickr.com/photos/christophervsmith/3382123801/in/pool-obamastreetart

Obama’s decision to quash the release of Iraqi prison torture photographs has welled across the journo networks today. It began as a rumour and then confirmed by the Huffington Post, New York Times and other major news outlets.

Last month, I blogged about ACLUs legal victory and announcement of images release on May 28th. I told you to keep the date in mind as the images were sure to be a thwack on the retina – of course, not half as bad as some of the thwacks of twisted acts meted out by American rank and file under America military order.

I even went as far to say that Obama – with seeming little control – would possibly suffer at the fate of an early leak. Well, Obama’s done his u-turn and it looks like he might stop their release. He gets some support from Tomasky at the Guardian, but I can’t buy this argument. Obviously, Obama’s worried about the safety of his troops but the rest of us are worried about Cheney et al. getting off scott-free. The official line is that the Abu Ghraib abuses have been investigated fully, but in truth 25 low ranking officers were hung out to dry. There was no accountability further up the chain.

We should bear in mind that these are new images to the public and media, but not to politicians and internal investigators, and this is not the first time images have been suppressed and challenged.

The military’s mood was one of relative calm last month, with army investigators going on record that “these images are not as near as bad as Abu Ghraib”, but some are recalling long forgotten testimonies from 2004, namely by Seymour Hersh, here, here and here.

Hersh alleged that the children of female prisoners were sodomized in front of their mothers. These assertions were made on two occasions in 2004 – during a speech at the University of Chicago and at an ACLU conference.

There were audio files of these speeches online, but they do not seem to be operating. ACLU will have this on file nonetheless. And, in any case, Information Clearing House has a transcript of Hersh’s statements, from which I quote below:

Some of the worst things that happened that you don’t know about. OK? Videos. There are women there. Some of you may have read that they were passing letters out, communications out to their men. This is at [Abu Ghraib], which is about 30 miles from Baghdad — 30 kilometers, maybe, just 20 miles, I’m not sure whether it’s — anyway. The women were passing messages out saying please come and kill me because of what’s happened. And basically what happened is that those women who were arrested with young boys, children, in cases that have been recorded, the boys were sodomized, with the cameras rolling, and the worst above all of them is the soundtrack of the boys shrieking. That your government has, and they’re in total terror it’s going to come out. It’s impossible to say to yourself, how did we get there, who are we, who are these people that sent us there.

When I did My Lai, I was very troubled, like anybody in his right mind would be about what happened, and I ended up in something I wrote saying, in the end, I said, the people that did the killing were as much victims as the people they killed, because of the scars they had.

I can tell you some of the personal stories of some of the people who were in these units who witnessed this. I can also tell you written complaints were made to the highest officers. And so we’re dealing with an enormous, massive amount of criminal wrong-doing that was covered up at the highest command out there and higher. And we have to get to it, and we will. And we will, I mean, you know, there’s enough out there, they can’t.

And finally, if you thought you’d experienced the depravity of Abu Ghraib via the pictures – and if you thought you understood the extent to the crimes – you’d be wrong. This Guardian article, quoting Washington Post relays the testimony of a detainee witness to juvenile rape.

Detainee, Kasim Hilas, describes the rape of an Iraqi boy by a man in uniform, whose name has been blacked out of the statement, but who appears to be a translator working for the army.

“I saw [name blacked out] fucking a kid, his age would be about 15-18 years. The kid was hurting very bad and they covered all the doors with sheets. Then when I heard the screaming I climbed the door because on top it wasn’t covered and I saw [blacked out], who was wearing the military uniform putting his dick in the little kid’s ass,” Mr Hilas told military investigators. “I couldn’t see the face of the kid because his face wasn’t in front of the door. And the female soldier was taking pictures.”

It is not clear from the testimony whether the rapist described by Mr Hilas was working for a private contractor or was a US soldier. A private contractor was arrested after the Taguba investigation was completed, but was freed when it was discovered the army had no jurisdiction over him under military or Iraqi law.

IF THE IMAGES PEGGED FOR RELEASE ON THE 28TH ARE TO STIR UP FRESH INQUIRY INTO SEXUAL ABUSE OF JUVENILES THEN OBAMA HAS A SERIOUS PROBLEM.

Detainee on Box Stencil. By Steve Reed. Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/sreed99342/2077223377/

Author’s Note: I am taking my lead from Michael Tomasky for this blog post tying Obama’s call for a block on the release of images to the worst case scenario (sexual torture). Bear in mind that the buzz has been over 44 images – why, I don’t know – but over 2,000 were/are set to be released on May 28th. Also bear in mind that the images are said to be predominantly from facilities other than Abu Ghraib. There are a lot of unknowns in this matter. Nevertheless, I am sure of two things: 1) there is more visual evidence of abuse in existence and 2) Obama is obstructing the release of the latest evidence. Time will tell how these two variables cross or diverge.

First image by photographer Christopher V. Smith whose work can be found on his Flickr profile.

Second image by Steve Reed, whose work is on his Flickr profile and blog Shadows & Light.

In Germany, as in most European nations, prisons often lie within towns and cities; European prisons & jails are older than the housing estates and urban developments that, ultimately, came to surround them.

In Britain, castle-like Victorian-era prisons were the dominant type until the seventies when they were replaced by draft-proof, medium-sized institutions in rural locations. Bricks and mortar made way for concrete & razor wire. That said, a few town-centre “citadels” such as Preston Prison and Lancaster Castle still operate within Her Majesty’s Prison Service, the latter dating back to the 14th century!

In the American penal landscape, a high proportion of prisons (and all new builds) are outside of conurbations – sometimes isolated in the mountains or desert, sometimes just within grasp of a rural town to prop or establish a local economy.

Christiane Feser‘s photographs could not be mistaken as American, just as the New Topographics couldn’t be mistaken for anything but American. I don’t want to say Feser’s series Prisons is typically German, because I don’t know what that means. Instead, I will say it is typically Northern European. Feser’s photographs embody the spirit of pedantic spatial ordering which I have observed not only in Britain and Germany, but also Austria and the Netherlands.

We don’t know the specific locations of these prisons so we can not know the construction dates. Given the carceral/residential interplay we can say that if Feser’s images aren’t about the zoning of space, they are about a time before zoning dominated civic-planning.

“When I photographed the prisons I was interested in how these prison walls are embedded in the neighbourhoods,” said Ms. Feser via email. “How the neighbours live with the walls. There are different strategies. Its a little bit complicated for me to write about it in English …” Feser’s images do the talking.

Feser’s world is one of silence, order and manicured nature. Her images evince a harmony between the prison, its neighbours and vice-versa. We witness no trauma here.

Feser has obviously decided to omit humans from her compositions. The neighbourhoods are well tended and so presumably inhabited. One presumes the neighbourhoods are occupied daily, and yet we see no cars in driveways nor bikes on the street. Feser almost suspends belief. Are these actual places? Is this a toy-town?

Why does Feser rely on manicured topiary and brick pointing of the absent inhabitants to illustrate the “different strategies”? Is Feser suggesting a common psychology between prisoners and residents?

Have the neighbours adopted psychologies of seclusion and discipline as exist in the prison next door? Can penal strategies of control transfer by osmosis through prison walls and throughout a community? Or are certain personalities attracted to these new build estates? Are a portion of these homes reserved for prison staff? Or has Feser’s clever framing and omissions just led the viewer along these lines of inquiry?

Many would think in this peculiar carceral/residential inter-relationship the prison dominates, overbears. I doubt it. I contend those who live in such locales influence the institution also. The two agents in this relationship aren’t separate; they are drawn to one another and they overlap.

Feser uses visual devices to point toward this overlap. Angles of the oblique walls, dead ends, tended verges and brown-toned brickwork repeat through the series; sometimes these elements are part of prison fabric, sometimes part of a house.

There exists no hierarchical coda in Feser’s images as all the surfaces are equal. One has to pay attention to figure out which architecture is carceral, and which is not. Even the barbed wire doesn’t confirm it totally as (in England at least) one commonly sees barbed wire and glass shards lining the walls of merchant-yards and back alleys.

Feser’s photographs cradle a palette of grey concrete & skies; dense greens and the browns of brick & mortar. This is Germany, but it could as easily be Lancashire housing estates, Merseyside new towns or the reclaimed industrial sites of Scottish cities.

So how about it America? You are the land of the suburb and subdivision. You may not be familiar with a socio-spatial history that favours the awkward in-fill of urban and semi-urban space over the encroachment on to undeveloped land. It’s alright. Prisons needn’t be invisible and we needn’t be afraid. Locks and keys work as well on your street as they do in up-state, high-pain, back-water seclusion!

The location of prisons matters because when prisoners are sent to facilities on the other side of the state, families are likely to visit less. The commitment of time and money required to make such a lengthy trip usually precludes the poorest families from the essential and simple act of visiting a loved one. Research has shown the largest single factor in a prisoner successfully reentering society and not re-offending is the maintenance of family ties and the continued support it provides.

All images © Christiane Feser. Used with permission.

Two weeks ago, I was lolling in bed with the local NPR station airing in the background. It was one of those times when the free sway between sleep and wake buoyed the iterations feeding the subconscious. The words from the waves were deep and clear and the meanings my own to navigate without the filters of plain-sailing reality. The whole reverie was quite comforting. Rick Steves was at the mic and his words about ‘otherness’ charted the same course my thoughts had – many times previous.

Rick Steves is a travel journalist who is keen to see (American) tourists embrace an less-disneyfied, more-connected type of travel. He was answering a listener’s question about border towns, but instead of responding with specific tales from specific towns Steves was much more interested in excavating the structure of thought that defines the appreciation of border towns. What parameters of thought do we rely on when thinking about borders? Why do border towns gain notoriety? Why do border towns evoke fear, love, misery and hope? Why do borders bring people escape, opportunity, exploitation, largess and threat?

Before I quote Steves’ answer, I want to put his response into the context of my somnolent appreciation. Borders delineate two forms of existence; the difference sometimes extreme, and sometimes barely recognizable. Nevertheless, borders are defined by the imposition of different rules on either side. Borders have many manifestations and, unfortunately, walls have become a recent embodiment of bi-national relations.

Prisons also have central to their function the imposition of one set of rules on one side of the wall in order to maintain the prevailing rules on the other. A border delineates the exterior reaches of a territory, whereas the prison exists within the interior. The prison, historically, is less porous than a border and is more heavily policed – although in the case of the US border the distinctions are becoming less evident.

In short, I believe prisons (and other sites of incarceration) should be thought as systems of state/corporate authority, based on the lowest common economic denominators, based on the concealment of activity and the creation of an excluded class whose definitions are open to manipulation. In the most tragic interpretation of Edward Said’s theory, I contend that on the other side of prison walls, just as on the other side of border walls, “The Other” exists.

And so, Rick Steves:

I am standing on top of the rock of Gibraltar. I read that this is the only place on the planet where you can see two continents and see two seas come together. There are tiderips. It is a confused sea, but there is food there. And all the seagulls go to the tiderips and the salmon are underneath, and the swarms of little herring, and so on … and it is a fascinating thing when two bodies of water come together. It makes danger for your boat, but there is food there and that is where the fish come and that is where people go for sustenance and that where the action is. And I am standing on the rock overlooking the tiderips. And there’s the ocean going freighters and the local people worried about the maritime environment. There are the stresses between Christianity and Islam which is just over [the water] in Africa, and that morning I was stood in a church, which was built on the ruins of a mosque, which was built on the ruins of a church, which itself was built on the ruins of a pre-Christian holy site! And if you can go to the places where cultures come together that’s where you have tension and you can have opportunity.

Translation – expect, witness and embrace difference in novel ways. Choose between tension and opportunity.

We have tension now [in America]. If we have unsophisticated political leadership, and dumbed down media and an electorate that doesn’t expect its neighbors to be nuanced and complex and more thoughtful in how they approach these challenges right now then the places where these cultures come together will be a big, expensive headache. And if we have smarter leadership and we engage the world, then the places where the cultures come together will be a plus. When we have cultures coming together in a constructive way it becomes a blessing instead of a curse. If it’s “my way or the highway” and if it’s just shock and awe then it’s not going to work.

Steves wasn’t talking about methods of incarceration, but his structuralist description that clearly defined ecological, socio-cultural, tectonic and psychological tensions of borders reflected society’s same unconscious antagonism that I have observed in popular thought. At best the American public is apathetic; at worst, it breeds searing hatred of those on the other side of the walls.

In the case of prisons, the American public has been duped by dumbed down media – Cops, News bulletins disproportionately reporting crime, movies that exploit false stereotypes of prisons and prisoners. In the case of prisons, the American public has been scared by the shock and awe tactics of politicians – “Tough on Crime” rhetoric. In the case of prisons, the American public has been fooled by an unsophisticated civic leadership that panders to the public’s desire to not think any further than “throwing criminals” in prison – massive prison expansion, state budgets dominated by corrections spending. Prisons have become a big expensive headache.

We need to stop ignoring the harsh facts about prisons and we need to bring them closer to our society, in which they sit. We need to reevaluate the failed prison expansion experiment of the past 30 years and we need to look upon the problem as an opportunity for sensible decision-making. We need to stop our fear and anger from dictating our reason and we need to analyse the system and not judge those subject to it.

The prison is a focus of hard emotions for those who reside, work and visit. It is a tumultuous place with fierce tensions. Those of us on the side of the wall with more resources and opportunity should think about how we can affect existence on the other side. We shouldn’t be fooled by the physical barrier dividing us because history has only ever shown that walls are temporary and humanity lasting. We should not allow the concrete walls to harden a psychological barrier to the communities on the other side. We should not find excuses – we should find opportunities.

And with this said, it is apparent why photography as a medium appeals so personally to me. Of all media, photography seems one of the most responsible. Photography has a history of social responsibility. Photography, some would argue, takes a bit more effort than TV. If photography is to be allied to the moving image, I prefer it allied to cinema and film. I hope to support this theory over many more posts.

Image notes:

Eros Hoagland has recently done some excellent work in newly constructed prisons of Southern California that I shall return to soon.

Jon Lowenstein is extending his portfolio rapidly. He rightly won plaudits for his documentary work in South Chicago schools back in 2005. He continues his commitment to Chicago.

Glyph Hunter, by his own admission, got lucky and caught a great exposure.

Jacob Holdt’s America: Hitch-hiking, Poverty, Racism, Prisons, Death and Love

May 19, 2009 in Activist Art, Documentary, Historical | Tags: America, Anti-Racism, Comment, Death, Drugs Addiction, Inequality, Jacob Holdt, Love, Murder, Philosophy, Poverty, Prison, Prisons, Problems, Social, Violence | by petebrook | Leave a comment

Jacob Holdt presenting at the New York Photo Festival, 2009. Screen shot from WTJ? Video.

In 2008 it was Ballen. In 2009 it was Jacob Holdt; The highlight of the New York Photo Festival.

I have been a fan of Holdt’s work for a couple of years now. Longer than some and not a fraction as long as others. Holdt has lived across the globe as an activist against racism and a harbinger of love for nearly four decades.

In 2008, Jacob Holdt was nominated for the Deutsche Borse Prize eventually losing out to Esko Männikkö. It was a shrewd shortlisting by a notoriously urbane committee at Deutsche. Holdt’s life and productive trajectory is his own, and much like Ballen does not conform to any norms of expected photographic career paths.

Any nomination – any praise – is purely a recognition of Holdt’s philosophy, his “vagabond days”, his trust in fellow humans and his rejection of stereotypes, fear and pride. Holdt does not revere photography as others may, “Photography never interested me. Photography was for me only a tool for social change.”

© Jacob Holdt

I watched Holdt’s presentation without expectation. I was, in truth, very surprised by the number of times he referred to his subjects – his friends – spending time in prison. It seemed only death trumped incarceration in terms of frequency amongst his circle of friends.

Prison Meal on Toilet © Jacob Holdt. Through a “mysterious mistake” I got locked up in this California prison with my camera and had plenty of time to follow the daily life of my co-inmates. Food was served in their cells where the only table was their toilet.

Slide after slide: “I can’t remember the number of times I have helped him get out of prison” and, “He’s in prison, now” or “He’s doing well now. He was in prison, but now he is out, has a family, and is doing well.”

Holdt described his method of finding community. Upon arrival in a new place, he would visit the police station and ask where the highest homicide rate was. He’d go to the answer.

Violence was tied up with poverty, was tied up with drugs, was tied up with deprivation, was tied up with hurt, was tied up with punishment and was tied up with prison – usually long sentencing.

Holdt’s series straddles the massive prison expansion experiment of America that began in the 1980s. Also enveloped are the crack epidemics, the racial fragmentation of urban populations and the relocation of middle classes to the suburbs. Holdt’s photographs are the mirror to racial economic inequalities.

Dad in Prison © Jacob Holdt. Alphonso has often entertained my college students about how he and the other criminals in Baltimore planned to mug me when they first saw me in their ghetto. However, we became good friends, but some time later he got a 6 year prison term. Here are the daughters Alfrida and Joann seen when they told me about it at my return. Today Alphonso has found God with the help of these two daughters who are now both ministers.

Holdt doesn’t play the blame game. Just as institutions and corporations walked all over many African Americans in Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, and states across the South, so too did people step on each other, “This is a photo of a man the night after he shot his own brother in the head.” The next night, he was out stealing again and soon after was convicted for another crime and served 16 years in prison.

Holdt only makes excuses for the failings of his friends insomuch as their mistakes are more likely – almost inevitable – set in the context of their life experience. He doesn’t jump in, drive-by, photo some ghetto-shots nor cadge some poverty-porn. Holdt involves himself directly and tries to open other avenues.

He and his team has lectured across the globe running anti-racism workshops. Holdt had ex-cons sell his anti-racism book on the streets when they were released from prisons without opportunity. He offered pushers the chance to sell his books instead of dope. Sometimes he saw the money and sometimes not, “But, it was never about the money” Holdt adds.

Prisoner cleaning up on Palm Beach. © Jacob Holdt

One of the most sobering facts of the talk was a double mention of Lowell Correctional Institution in Florida. It was the only facility referred to by name and twice Holdt named friends who’d spent time inside. Lowell is a women’s facility. The female prison population of America has quadrupled in the past 25 years. It is still expanding at a far faster rate than the male prison population. Women’s super-prisons are singularly an American phenomenon. Holdt dropped as an aside, “I have three friends with grandmothers in prisons.”

If he could help, he would. Holdt described a struggling young lady who he desperately wanted to get on staff of American Pictures, but in 1986 she was too strung out on crack. In 1994 he visited her in prison. In 2004 she was released. In 2007 she was still out and Holdt photographed her with her son.

He photographed mothers, lovers, father and sons behind bars. In one case, when the father was convicted the son turned to crime to keep enough money coming in to support the family. He soon joined his dad in prison.

Prison Kiss © Jacob Holdt. I was visiting the friend of this inmate when his wife suddenly came on a visit.

But when it would be expected that Holdt may be too deep inside the experience of the poor Black experience, he took the chance to live amid the poor White experience.

Poor whites at a Klan gathering in Alabama. © Jacob Holdt

In 2002, Holdt had the opportunity to live with the Ku Klux Klan. He became pals with the Grand Dragon and his family.

“I have spent my life photographing hurt people.” The KKK members were no different. The leader had been abused as a child, subject to incest and beatings. Holdt presumed this but it was confirmed around the time the leader was sent to prison for 130 years for murder.

Holdt moved in with Pamela, the leaders wife, to support her in her husbands absence. Also in his absence he brought the unlikeliest of people together.

Pamela with white friend (Jacob Holdt). © Jacob Holdt

Pamela with black friend. © Jacob Holdt

During this time and only through informal discussion did Holdt learn that the man was innocent – he had voluntarily gone to prison to spare his son, the real culprit, from conviction for a hate crime.

Holdt petitioned and won his release. The former Grand Dragon was unemployed upon release and went on to sell Holdt’s anti-racism book on the streets … just as the dope-dealers of Philly had 15 years earlier.

Holdt’s presentation confirmed to me that the prison is inextricably linked with the social history of America. But this should not be surprising in a society so violent. Holdt paints a portrait of America from the 70s through to today in which the poorest people (both Black and White) held the monopoly on violence, disease, depression, addiction and struggle.

When Holdt was in Africa he showed people there his images of African-Americans suffering. Africans thought the Black communities of America would fare better in Africa, “Why don’t they come back here?”

Two unemployed Vietnam veterans at wall on 3rd St. © Jacob Holdt

Given the situations he walked into, some may think Holdt is fortunate to still be alive but having armed himself with love he made his own luck … and friends.

Check out more on Jacob Holdt here and here. Here is an article in support of his hitch-hiking activity.

Holdt’s incredible 20,000 image archive American Pictures.

WTJ? 70 minute video of his NYPF presentation.