You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Texas’ tag.

‘Duck and I’ © Pete Brook

Last month I went to Big Bend National Park, on the border with Texas and Mexico. The Chihuahuan desert is very hot during the day, even in spring. We took an 18-mile day hike, walking before and immediately following sunrise and later in the three hours before sundown.

On the trek out I was surprised to see (and super-amused by) the artistry of some ducks (called cairns in the UK); even in the inhospitable desert, some folks had taken the time and care to build these things. It occurred to me that I’d seen typologies of most things but not these essential, non-owned, geo-marking, petra-sculptures. On the way back, I photographed them.

As I have said before, I am not a photographer and I rarely want to share my images but I’ll share this bit of fun.

‘ROBODUCK’ © Pete Brook

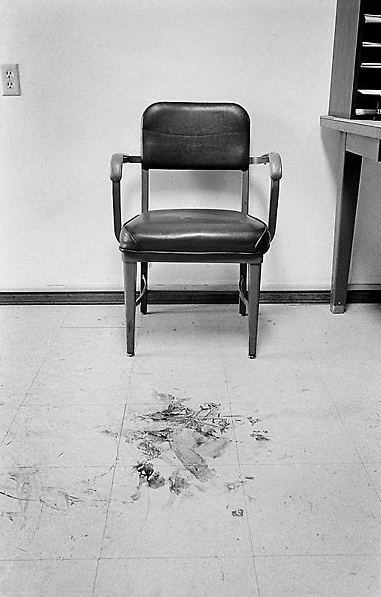

Susan Wright. © Matthew Rainwaters

Matthew Rainwaters‘ Offender, an assignment for Esquire and Texas Monthly, depicts “two very different inmates inside the Texas Department of Corrections.”

The first is some bloke with a history of fraud and a penchant for escape.

I am more interested in juxtaposing Rainwaters’ portraits of a husband-killer and the prosecution attorney.

LADIES

Susan Wright was convicted of murder after stabbing her husband 193 times. She was recently granted an appeal and may be released after re-sentencing.

Prosecuting attorney Kelly Preistner doesn’t buy the battered woman’s syndrome defense. During closing arguments she reenacted stabbing her assistant 193 times for the jury.

Kelly Priestner. © Matthew Rainwaters

COMMERCIAL PHOTOGRAPHY

Generally, I don’t know what to make of commercial work and portraiture done inside prisons. I think I’ve only featured it once before on Prison Photography with a nod to Andrew Hetherington’s work for Wired on a story about cell phones and security breaches.

Evidently, Rainwaters’ is motivated to go beyond the requirements of assignment; he’s got the prison photography bug!

In an interview over at electronic beats he describes the fortune of the two stories coming at once, but that they catalysed a body of work upon which he wants to expand:

Rainwaters goes onto explain he hopes to photograph at Guantanamo. This leap is remarkable. I would not expect a commercial or editorial photographer to make such a transition. For me it stands to reason that one discusses Guantanamo and illegal US prisons in the same context as homeland penitentiaries, but I don’t expect others to always hold the same opinion. That a photographer is pressing this line is intriguing.

I’ll be eager to show Rainwaters’ Guantanamo work when it surfaces.

– – –

You can also see the selection of Rainwaters’ work at Behance.

Thanks to Scott for the tip.

Ken Light is a career photojournalist and a professor of photojournalism at Berkeley. If anyone is going to push back against the abuse of photographers rights, it’d be him right?

Well, he did. He won a small but symbolic $558

Last year, Light licensed his image of Cameron Todd Willingham to several media outlets coinciding with The New Yorker‘s exposé of dodgy arson forensics and the probable innocence of Willingham.

Current TV was not one of those he dealt with, yet they displayed Light’s image for a couple of months.

Light avoided federal court because it is costly and long-winded and filed a small-claims suit in San Francisco. PDN explains:

What is interesting here, is Light wonders avoiding the impractical, less-reflexive, federal route could be a better option for photographers:

“Yes, I got much less than I thought I deserved. [But] Maybe if we attacked in small claims courts and won, some of these companies might be more careful,”

I think Light has a good point and proven a repeatable tactic.

___________________________________________

Postscript: In the summer, I did multiple interviews and one of those was with Light about photographing on Texas’ death row. Everyday, I look at that untranscribed audio file and beat myself up that I haven’t published yet. It’s coming … I promise.

Alabama Death House Prison, Grady, AL, 2004. Silver print photograph. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Stephen Tourlentes photographs prisons only at night for it is then they change the horizon. Social division and ignorance contributed to America’s rapid prison growth. Tourlentes’ lurking architectures are embodiments of our shared fears. In the world Tourlentes proposes, light haunts; it is metaphor for our psycho-social fears and denial. Prisons are our bogeyman.

These prisons encroach upon our otherwise “safe” environments. Buzzing with the constant feedback of our carceral system, these photographs are the glower of a collective and captive menace. Hard to ignore, do we hide from the beacon-like reminders of our social failures, or can we use Tourlentes’ images as guiding light to better conscience?

Designed as closed systems, prisons illuminate the night and the world that built them purposefully outside of its boundaries. “It’s a bit like sonic feedback … maybe it’s the feedback of exile,” says Tourlentes.

Stephen Tourlentes has been photographing prisons since 1996. His many series – and portfolio as a whole – has received plaudits and secured funding from organisations including the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Massachusetts Cultural Council and Artadia.

Stephen was kind enough to take the time to answer Prison Photography‘s questions submitted via email.

Penn State Death House Prison, Bellefonte, PA, 2003. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Carson City, Nevada, Death House, 2002. Gelatin silver print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Blythe Prison, California. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Pete Brook. You have traveled to many states? How many prisons have you photographed in total?

Stephen Tourlentes. I’ve photographed in 46 states. Quite the trip considering many of the places I photograph are located on dead-end roads. My best guess is I’ve photographed close to 100 prisons so far.

PB. How do you choose the prisons to photograph?

ST. Well I sort of visually stumbled onto photographing prisons when they built one in the town I grew up in Illinois. It took me awhile to recognize this as a path to explore. I noticed that the new prison visually changed the horizon at night. I began to notice them more and more when I traveled and my curiosity got the best of me.

There is lots of planning that goes into it but I rely on my instinct ultimately. The Internet has been extremely helpful. There are three main paths to follow 1. State departments of corrections 2. The Federal Bureau of Prisons and 3. Private prisons. Usually I look for the density of institutions from these sources and search for the cheapest plane ticket that would land me near them.

Structurally the newer prisons are very similar so it’s the landscape they inhabit that becomes important in differentiating them from each other. Photographing them at night has made illumination important. Usually medium and maximum-security prisons have the most perimeter lighting. An interesting sidebar to that is male institutions often tend to have more lighting than female institutions even if the security level is the same.

Holliday Unit, Huntsville, Texas, 2001. Gelatin silver print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Springtown State Prison, Oklahoma, 2003. Archival pigment print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Death House Prison, Rawlins, Wyoming, 2000. Archival pigment print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Arkansas Death House, Prison, Grady, AK, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. Are there any notorious prisons that you want to photograph or avoid precisely because of their name?

ST. No I’m equally curious and surprised by each one I visit. There are certain ones that I would like to re-visit to try another angle or see during a different time of year. I usually go to each place with some sort of expectation that is completely wrong and requires me to really be able to shift gears on the fly.

PB. You have described the Prison as an “Important icon” and as a “General failure of our society”. Can you expand on those ideas?

ST. Well the sheer number of prisons built in this country over the last 25 years has put us in a league of our own regarding the number of people incarcerated. We have chosen to lock up people at the expense of providing services to children and schools that might have helped to prevent such a spike in prison population.

The failure is being a reactive rather than a proactive society. I feel that the prison system has become a social engineering plan that in part deals with our lack of interest in developing more humanistic support systems for society.

PB. It seems that America’s prison industrial complex is an elephant in the room. Do you agree with this point of view? Are the American public (and, dare I say it, taxpayers) in a state of denial?

ST. I don’t know if it’s denial or fear. It seems that it is easier to build a prison in most states than it is a new elementary school. Horrific crimes garner headlines and seem to monopolize attention away from other types of social services and infrastructure that might help to reduce the size of the criminal justice system. This appetite for punishment as justice often serves a political purpose rather than finding a preventative or rehabilitative response to societies ills.

State Prison, Dannemora, NY, 2004. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Prison, Castaic, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Federal Prison, Atwater, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Utah State Death House Complex, Draper, UT, 2002. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. How do you think artistic ventures such as yours compare with political will and legal policy as means to bring the importance of an issue, such as prison expansion, into the public sphere?

ST. I think artists have always participated in bringing issues to the surface through their work. It’s a way of bearing witness to something that collectively is difficult to follow. Sometimes an artist’s interpretation touches a different nerve and if lucky the work reverberates longer than the typical news cycle.

PB. In your attempt with this work to “connect the outside world with these institutions”, what parameters define that attempt a success?

ST. I’m not sure it ever is… I guess that’s part of what drives me to respond to these places. These prisons are meant to be closed systems; so my visual intrigue comes when the landscape is illuminated back by a system (a prison) that was built by the world outside its boundaries. It’s a bit like sonic feedback… maybe it’s the feedback of exile.

PB. Are you familiar with Sandow Birk’s paintings and series, Prisonation? In terms of obscuring the subject and luring the viewer in, do you think you operate similar devices in different media?

ST. Yes I think they are related. I like his paintings quite a lot. The first time I saw them I imagined that we could have been out there at the same time and crossed paths.

PB. Many of your prints are have the moniker “Death House” in them, Explain this.

ST. I find it difficult to comprehend that in a modern civilized society that state sanctioned executions are still used by the criminal justice system. The Death House series became a subset of the overall project as I learned more about the American prison system. There are 38 states that have capital punishment laws on the books. Usually each of these 38 states has one prison where these sentences are carried out. I became interested in the idea that the law of the land differed depending on a set of geographical boundaries.

Federal Prison, Victorville, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Prison Complex, Florence, AZ, 2004. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Lancaster State Prison, Lancaster, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. Have you identified different reactions from different prison authorities, in different states, to your work?

ST. The guards tend not to appreciate when I am making the images unannounced. Sometimes I’m on prison property but often I’m on adjacent land that makes for interesting interactions with the people that live around these institutions. I’ve had my share of difficult moments and it makes sense why. The warden at Angola prison in Louisiana was by far the most hospitable which surprised me since I arrived unannounced.

PB. What percentage of prisons do you seek permission from before setting up your equipment?

ST. I usually only do it as a last resort. I’ve found that the administrative side of navigating the various prison and state officials was too time consuming and difficult. They like to have lots of information and exact schedules that usually don’t sync with the inherent difficulty of making an interesting photograph. I make my life harder by photographing in the middle of the night. The third shift tends to be a little less PR friendly.

PB. What would you expect the reaction to be to your work in the ‘prison-towns’ of Northern California, West Texan plains or Mississippi delta? Town’s that have come to rely on the prison for their local economy?

ST. You know it’s interesting because a community that is willing to support a prison is not looking for style points, they want jobs. Often I’m struck by how people accept this institution as neighbors.

I stumbled upon a private prison while traveling in Mississippi in 2007. I was in Tutweiler, MS and I asked a local if that was the Parchman prison on the horizon. He said no that it was the “Hawaiian” prison. All the inmates had been contracted out of the Hawaiian prison system into this private prison recently built in Mississippi. The town and region are very poor so the private prison is an economic lifeline for jobs.

The growth of the prison economy reflects the difficult economic policies in this country that have hit small rural communities particularly hard. These same economic conditions contribute to populating these prisons and creating the demand for new prisons. Unfortunately, many of these communities stake their economic survival on these places.

Kentucky State Death House, Prison, Eddyville, KY, 2003. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. You said earlier this year (Big, Red & Shiny) that you are nearly finished with Of Lengths and Measures. Is this an aesthetic/artistic or a practical decision?

ST. I’m not sure if I will really ever be done with it. From a practical side I would like to spend some time getting the entire body of work into a book form. I think by saying that it helps me to think that I am getting near the end. I do have other things I’m interested in, but the prison photographs feel like my best way to contribute to the conversation to change the way we do things.

________________________________________

Author’s note: Sincerest thanks to Stephen Tourlentes for his assistance and time with this article.

________________________________________

Stephen Tourlentes received his BFA from Knox College and an MFA (1988) from the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, where he is currently a professor of photography. His work is included in the collection at Princeton University, and has been exhibited at the Revolution Gallery, Michigan; Cranbook Art Museum, Michigan; and S.F. Camerawork, among others. Tourlentes has received a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, a Polaroid Corporation Grant, and a MacDowell Colony Fellowship.

________________________________________

This interview was designed in order to compliment the information already provided in another excellent online interview with Stephen Tourlentes by Jess T. Dugan at Big, Red & Shiny. (Highly recommended!)