You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

Carlos Javier Ortiz has been documenting the effects of gun violence on young people in Chicago for over seven years on a project called Too Young To Die. He is currently crowdfunding support to bookend, literally, the work.

We All We Got will be a photography book that brings seven years of Ortiz’ images together with interviews from parents and students from across Chicago and texts by Alex Kotlowitz (producer of the The Interrupters), Luke Anderson (teacher, North Lawndale College Prep) and Miles Harvey (assistant professor, DePaul University) among others.

Ortiz isn’t a flashy guy; he just gets the job done. He’s not only photographed for an extended period in the community but he’s also got involved directly with local organisations. It’s something he’s done for a long time. He’s thinking about solutions to gun violence among youth, which is one of the toughest issues in America.

The project deserves support. I think it’ll get the funds. I hope it does. Spread the word through Facebook, Twitter, Instah.

We All We Got has already had deserved coverage on NPR; New York Times Lens; CBS Evening News; Chicago Ideas Week; Museum of Contemporary Photography; Leica Blog; Pulitzer Center On Crisis Reporting; CNN blog; and CBC radio

Photo: “Me & Myself” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

ONO ŠTO SE VIDI A NE ČUJE

If you happen to be in Belgrade, Serbia over the next couple of weeks, I encourage you to head to the Kulturni Centar Beograda (KCB) and see Seen But Not Heard, an exhibition I’ve curated of photographs from American juvenile detention facilities. The show features photographs made by incarcerated youth in photography workshops coordinated by Steve Davis in Washington State and by As220 Youth in Rhode Island, as well as well known photographers Steve Liss, Ara Oshagan, Joseph Rodriguez and Richard Ross.

The invite to put together Seen But Not Heard — which is my first international solo curating gig — was kindly extended by Belgrade Raw, an impressive photo-collective who have operated as guest exhibition coordinators at the KCB’s Artget Gallery throughout 2013. Belgrade Raw called it’s year long program Raw Season. and it was 10 exhibitions strong, including Blake Andrews, Donald Weber and others. Here’s Belgrade Raw’s announcement for Seen But Not Heard.

I’ll update the blog next week with installation shots and a loooong list of acknowledgements (the hospitality, skills and hard work of everyone here has been so overwhelming.)

Beneath, is a long essay I wrote for Seen But Not Heard . Beneath that is a selection from the 200+ works in the exhibition. Beneath the works are the details of the photographer and/or program who made them.

Photo: “Flip” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

ESSAY

USING PHOTOGRAPHY TO COMMUNICATE NOT CONTROL

“Ten thousand pulpits and ten thousand presses are saying the good word for me all the time … Then that trivial little Kodak, that a child can carry in his pocket, gets up, uttering never a word, and knocks them dumb.”

– Mark Twain, writing satirically in the voice of King Leopold in condemnation of the Belgian’s brutal rule over the Congo Free State. King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1905).

The United States of America is addicted to incarceration. In the course of a year, 13.5 million Americans cycle through the country’s 5,000+ prisons and jails. On any given day, 2.2 million American’s are locked up — 60,500 of whom are children in juvenile correctional facilities or residential programs. The United States imprisons children at more than six times the rate of any other developed nation. With an average cost of $80,000/year to lock up a child under the age of 18, the United States spends more than $5 billion annually on youth detention.

What do we know of these spaces behind locked doors? What do we see of juvenile prisons? The short answer is, not a lot. However, photographs can provide some information — provided we approach them with caution and an informed eye.

Seen But Not Heard features the work of five well-known American photographers who have taken their cameras inside. Crucially, the exhibition also includes photographs made by incarcerated children on cameras delivered to them by arts educators and by staff of social justice organizations. Many of the children’s photographs are being exhibited for the first time.

Cameras are used by prison administrations to maintain security and enforce order, so when a camera is operated by a visiting photographer — and especially by a prisoner — a shift in the power relations occurs. All the images in Seen But Not Heard prompt urgent questions about what it means to be able document and what it means to be prohibited from documenting. What difference is there between being the maker of an image compared to being the subject of an image? What happens if you put kids behind the camera instead of in front of it? What stories do children tell that adults cannot? Can a camera can be a tool for artistic expression instead of an apparatus of control?

EXPRESSION

“Light Paintings” made by students of the Rhode Island Training School (RITS) prove a camera is essential to the artist’s toolkit. The anonymous RITS students’ images conjure angelic limbs and alter-egos from the dark. The images contain the frustration of incarceration; the longing of a (new) time; the aspirations of youth; the childishness of comic drawing. The photography outreach program taught by AS220, a community arts group of long-standing in Rhode Island, is an extension of workshops taught to teens in the free-world. In fact, children have graduated out of RITS and into the many studio arts programs offered by AS220 Youth in the town and neighborhoods of Providence, RI. An adult would or could never make these images; it is a privilege for us to share in them.

The workshops that Steve Davis coordinated in four youth detention centers in Washington State provide us a window into the incarcerated children’s lives. For legal reasons, at Remann Hall, no images could identify the girls and so Davis made use of pinhole cameras with long exposures. The girls treated the opportunity as one for performance enacting torment, official restraint procedures and bored isolation. The blurry images are eerie and evocative; as if the girls are capturing the moments in which they are disappearing from society’s view.

By contrast, the boys’ photographs are very much embedded in reality; they carried cameras outside of structured class time with instructions to make general images and construct photographs along a weekly theme. The boys had one another as immediate audience. We see unfiltered views of their activities, cells, day rooms, programs and priorities; we see costume, computer games, machismo posturing, childlike play and even boring moments. Accidentally they collectively constructed a visual narrative in which motifs such as t-shirts, playing cards and institutional furniture recur. The photographs would be monotonous were it not for the splashed of life the children provide — perfectly communicating why and how humans kept in boxes is not the natural order, nor the ideal circumstance.

MOTIVATIONS

The photographers in Seen But Not Heard all had different motivations for going inside. After the experience, they all had the same attitudes.

Without exception, the photographers’ experiences had them wide-eyed, sometimes angry, usually frustrated and certainly more conscious of the politics of incarceration. Consequently, they feel a responsibility to share their images and to describe youth prisons to many audiences.

Steve Liss had watched the children of a Texas juvenile prisons perform a choreographed marching routine for then Texas Governor G.W. Bush. After the ridiculous spectacle, the ridiculous Bush gave a ridiculous moral instruction to stay out of trouble. Liss was furious at the patronizing tone of the event and particularly Bush. As a press photographer, Liss had parachuted in and out of that prison as quick as his subject Bush did. He vowed that if Bush ever made it to be President, he’d return to Texas to photograph the children’s lives. Bush would never see those children, but perhaps the world should. It is alarming how often we see very young and tiny children subject to shackles and apparatus designed for dangerous 200+ lb. men. It’s as if the system is blind to the physicality of its young prisoners. That being the case, how can we presume they understand or provide for the more complex psychology of these children?

Joseph Rodriguez was locked up as a young man. He also experienced homelessness, for a time, and was addicted to drugs. He was sent to the infamous Riker’s Island prison in New York twice — first, for a minor charge related to his anti-war protest activity; second, for burglary. His mother could not afford the $500. He spent 3 months locked up awaiting his court date. Post-release, Rodriguez found photography and it gave him a means to process and describe the world. Having seen the inside, Rodriguez empathizes with children who are going through any prison system. More than 20 years after his incarceration, Rodriguez felt it a duty to use his storytelling skills to tell the stories of incarcerated children. In 1999, he photographed inside the San Francisco and Santa Clara Counties juvenile detention centers and followed children through the cells, courtrooms and counseling of the criminal justice system.

Ara Oshagan’s opportunity to photograph at the Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall (the largest juvenile prison in America) was pure happenstance. He met with Leslie Neale a documentary filmmaker for lunch on a Monday. Neale was filming inside the juvenile hall and needed a photographer to shoot b-roll. Oshagan was inside on the Tuesday. He was so moved by the experience that he applied for clearance to return on his own. He followed six youngsters as they progressed through their cases and, in some cases, into California’s adult prison system. Oshagan never felt like his photographs were enough to describe the emotions of the children and so he asked each of them to write poems and presents text and image as diptych. Random circumstance, fine slices of luck, peer pressure and other people’s decisions factor far more heavily in children’s lives than in adults’ lives. Throughout, Oshagan was constantly reminded how his subjects were very much like his own children.

Late in his career and having financial security through a Guggenheim fellowship and teaching sabbatical, Richard Ross turned his lens upon juvenile detention. Ross wanted to give advocates, legislators, educators the visual evidence on which to base discussion and policy. He provides his images for free to individuals and organizations doing work for the betterment of children’s lives.

Repeatedly, Ross met children who were themselves victims; frighteningly often he heard stories of psychological, physical and sexual abuse, homelessness, suicide attempts, addiction and illiteracy. Many kids locked up are from poor communities and a disproportionate number of youths detained are boys and girls of color. Ross observed some really positive interventions made by institutions (regular meals, counseling, positive male role models to name a few) but he saw the use of incarceration not as last resort but as routine.

WHY SHOULD WE CARE?

Unsurprisingly, many have lost faith in the juvenile prison system. Recent scandals have exposed systematic abuses.

In Pennsylvania, two judges accepted millions of dollars in kickbacks from a private prison company to sentence children to custody; in Texas, an inquiry uncovered over 1,000 cases of sexual assault by staff in the state’s juvenile justice system; in New York, on Riker’s Island it has been alleged that young gangs (referred to as “teams”) organized within the jail itself, and controlled and enforced the juvenile wings while the authorities turned a blind eye. The rivalries resulted in fights, stabbings and in one case death. The New York City Department of Corrections denies the allegations, but interestingly it was NYDOC employees that exposed the violence by leaking internal photographs to the Village Voice newspaper.

Nationally, the private company Youth Services International (YSI) inexplicably continues to operate despite being cited for ‘offenses ranging from condoning abuse of inmates to plying politicians with undisclosed gifts while seeking to secure state contracts’ by the Department of Justice and also New York, Florida, Maryland, Nevada and Texas.

Not only is being locked up ineffective as a deterrent in youths who have not reached full cognitive development and don’t understand the consequences of their actions, it can actually make a criminal out of a potentially law-abiding kid. Dr. Barry Krisberg, director of research at the Berkeley School of Law’s Institute on Law & Social Policy, says, “Young people [when detained] often get mixed in with those incarcerated on more serious offenses. Violence and victimization is common in juvenile facilities and it is known that exposure to such an environment accelerates a young person toward criminal behaviors.”

THE FUTURE

Given the lessons from the failed practices of incarcerating more and more children, States are adopting more progressive policies. Certainly, authorities are turning away from punishing acts such as truancy and delinquency with detention; acts that are not criminal for an adult but have in the past siphoned youths into the court system. But more than that, incarceration for youth is widely considered a last resort.

States that reduced juvenile confinement rates the most between 1997 and 2007 had the greatest declines in juvenile arrested for violent crimes. It’s proof that incarceration doesn’t solve crime. And, it might suggest incarceration damages communities. Following repeated abuse scandals in the California Youth Authority (CYA) facilities in the 90s, California carried forth the largest program of decarceration in U.S. history. Reducing its total number of youth prisons from 11 to 3 and slashing the CYA population by nearly 90%, California simultaneously witnessed a precipitous drop in violent crime committed by under-18s.

The U.S. still has a long way to go if it is to reverse decades of over-reliance on incarceration, but as the recent Supreme Court ruling banning Life Without Parole sentences for children suggests, it seems Americans hold less punitive attitudes when it comes to youth’s transgressions, as compared to the apathetic attitudes to adult prisoners.

We need to expect and applaud photography that depicts imprisoned children as they are — as citizens-in-the-making, as humans with as complex emotional needs as any of us, as not lost causes, as victims as much as they may have been victimizers, as our future, as individuals society must look to help and reintegrate and not discard. Photography can help us appreciate the complexity of the issues at hand. Used responsibly, it can bring us closer.

Photo: “Cash Rules Everything Around Me” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

Photo: “Icarus” by an anonymous student of photography workshop at the Rhode Island Training School, coordinated by AS220 Youth.

AS220

AS220 Youth is a free arts education program for young people ages 14-21, with a special focus on those in the care and custody of the state. AS220 Youth provides free studio-based classes in virtually all media including photography. Staff including photography coordinator Scott Lapham and photography instructor Miguel Rosario (who I met when I visited in 2011) help students build a portfolio with help from a staff advisor. AS220 Youth maintains long-term, supportive relationships with youth transitioning out of RITS and the Department of Children, Youth and Their Families (DCYF) care, and offers mentoring, transitional jobs, and financial support. AS220 Youth works to connect youth with professional opportunities in the arts — through exhibitions at the AS220 Gallery and others; through publication in the AS220 quarterly literary magazine called ‘The Hidden Truth’; and through securing photo-assistant jobs on commercial photo shoots for students.

Photo: Steve Liss. Prisoners, ages 10-16, wait in line to march back to their cells in the exercise yard at the Webb County Juvenile Detention facility.

Photo: Steve Liss. 10-year-old Alejandro has his mug shot taken at Webb County Juvenile Detention following his arrest for marijuana possession. Every day the inmates get smaller, and more confused about what brought them here. Psychiatrists say children do not react to punishment in the same way as adults. They learn more about becoming criminals than they do about becoming citizens. And one night of loneliness can be enough to prove their suspicion that nobody cares.

STEVE LISS

Steve Liss photographed in Texas 2001-2004. His book No Place For Children: Voices from Juvenile Detention (University of Texas Press, 2005) won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award in 2006.

Steve Liss worked as a Time Magazine photographer for 25 years, assigned to stories of social significance involving ordinary people. Forty-three of his photographs appeared on the cover of Time Magazine. For his work on juvenile justice, Liss was awarded a Soros Justice Media Fellowship (2004) for my work on domestic poverty he was awarded an Alicia Patterson Fellowship (2005). Recently, Liss received the Pictures of the Year International (PoYI) ‘World Understanding Award.’ Liss has taught graduate photojournalism at Columbia College, Chicago and Northwestern University.

Photo: Ara Oshagan, from the series ‘A Poor Imitation Of Death’

Photo: Ara Oshagan, from the series ‘A Poor Imitation Of Death’

ARA OSHAGAN

Ara Oshagan photographed inside the Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall and the California prison system. Oshagan’s book of this work A Poor Imitation of Death is to be published next year (Umbrage Books, 2014). Oshagan is twice a recipient of a California Council on the Humanities Major Grant for his documentary work on diaspora groups in Los Angeles.

Interested in the themes of identity, community and bearing witness, much of Ara Oshagan’s work focuses on the oral histories of survivors of the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Since 1995, Oshagan has been creating work for iwitness in collaboration with Levon Parian and the Genocide Project. Father Land, a book project made with his father, well-known author, Vahe Oshagan was published in 2010 by powerHouse books.

Photo: Steve Davis. ‘Tiny, Green Hill, 2000’

Photo: Anonymous student at Green Hill School. Photograph made in response to the prompt “Vulnerability” as part of photography workshop led by Steve Davis.

Photo: Anonymous student at Green Hill School. Discussing photographs made during workshop led by Steve Davis.

STEVE DAVIS

Steve Davis coordinated photography workshops in four facilities in Washington State (Maple Lane, Green Hill, Remann Hall and Oakridge) between 1997 and 2005. Simultaneously, Davis made portraits and photographs for his own series Captured Youth.

Davis is a documentary portrait and landscape photographer based in the Pacific Northwest. His work has appeared in Harper’s, the New York Times Magazine, Russian Esquire, and is in many collections, including the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, the Seattle Art Museum, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and the George Eastman House. He is a former 1st place recipient of the Santa Fe CENTER Project Competition, and two time winner of Washington Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowships. Davis is the Coordinator of Photography, Media Curator and adjunct faculty member of The Evergreen State College, Olympia, WA. Davis is represented by the James Harris Gallery, Seattle.

Photo: Joseph Rodriguez, from the series ‘Juvenile’

Photo: Joseph Rodriguez, from the series ‘Juvenile’

JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ

Joseph Rodriguez photographed in the San Francisco County Jails 2001-2004. The work is collected in his book Juvenile (PowerHouse Books, 2004)

Joseph Rodriguez is a documentary photographer from Brooklyn, New York. He studied photography in the School of Visual Arts and in the Photojournalism and Documentary Photography Program at the International Center of Photography in New York City. Rodriguez’s work had been exhibited at Galleri Kontrast, Stockholm, Sweden; The African American Museum, Philadelphia, PA; The Fototeca, Havana, Cuba; Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, Birmingham, Alabama, Open Society Institute’s Moving Walls, New York; Frieda and Roy Furman Gallery at the Walter Reade Theater at the Lincoln Center; and the Kari Kenneti Gallery Helsinki, Finland. In 2001 the Juvenile Justice website, featuring Joseph Rodriguez’s photographs, launched in partnership with the Human Rights Watch International Film Festival High School Pilot Program. He teaches at New York University, the International Center of Photography, New York. Rodriguez is the past recipient if Alicia Patterson Journalism Fellowship in 1993 photographing communities in East Los Angeles.

Photo: Photo: Richard Ross. Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall. Downey, California.

RICHARD ROSS

Richard Ross is a photographer and professor of art at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Juvenile-In-Justice (2006-ongoing) “turns a lens on the placement and treatment of American juveniles housed by law in facilities that treat, confine, punish, assist and, occasionally, harm them,” says Ross.

A book Juvenile in Justice (self-published, 2012) and traveling exhibition continue to circulate the work. Ross collaborates with juvenile justice stakeholders and uses the images as catalysts for change. For Juvenile-In-Justice, Richard Ross photographed in over 40 U.S. states in 350 facilities, met and interviewed approximately 1,000 children. Juvenile-In-Justice published on CBS News, WIRED, NPR, PBS Newshour, ProPublica, and Harper’s Magazine, for which it was awarded the 2012 ASME Award for Best News and Documentary Photography.

We remember the TV images of Nelson Mandela in a grey suit, in bright sunlight, walking free from prison in 1990. We might not know that he could have walked free five years earlier. The reason he did not is because the offer made to him by then State President of South Africa, P. W. Botha was conditional. The conditions basically required Mandela to retire in silence, abandon everything he had stood up for, and went against his responsibilities toward his political supporters.

Mandela once said, “In prison, you come face to face with time. There is nothing more terrifying.” To learn that he refused release after 22 years of incarceration, despite the terror of it, is more proof of Mandela’s unwavering pursuit of justice.

In 1962, Mandela was arrested, convicted of sabotage and conspiracy to overthrow the government, and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Rivonia Trial. He was imprisoned for nearly 20 years on Robben Island until a 1982 transfer to Pollsmoor Prison. Perhaps (?) another lesser known fact is that Mandela was a keen boxer. He boxed to maintain health and discipline, so I’ve included a couple of images of Mandela training — one from 1950 before his imprisonment (below) and one from a prison yard (bottom).

To keep fit, Nelson Mandela, solicitor, was at Jerry Moloi’s boxing gym at Orlando every evening. He’s shadow-sparring with Moloi (right) a professional featherweight. As the biggest case in South Africa’s history lumbered to the end of its first stage this August 1957, the 156 accused men and women wondered how many of them would be back in court again. The 156 national leaders had first appeared at a preparatory examination into treason at the end of 1956, in the specially constructd court at the Drill Hall, Johannesburg; they had spent their lives in and out of court for most of 1957; and they could now see the possibility of the same prospect for the third calendar year, 1958, if they were committed for trial in the Supreme Court. (Photograph by Drum photographer © Baileys Archive)

It’s difficult to know what to say upon the death of any man, but particularly a man who shaped history. Therefore, it was a treat, an inspiration (and a writer’s let-off) to find Mandela’s inspiring rejection of Botha’s offer on the UCSC Library website:

On 31 January 1985, Botha, speaking in parliament, offered Mandela his freedom on condition that he ‘unconditionally rejected violence as a political weapon’. This was the sixth such offer, earlier ones stipulating that he accept exile in the Transkei. His daughter Zinzi read Mandela’s reply to this offer to a mass meeting in Jabulani Stadium, Soweto, on 10 February, 1985. This was the text of his response as read publicly by Zinzi:

I am a member of the African National Congress. I have always been a member of the African National Congress and I will remain a member of the African National Congress until the day I die. Oliver Tambo is much more than a brother to me. He is my greatest friend and comrade for nearly fifty years. If there is any one amongst you who cherishes my freedom, Oliver Tambo cherishes it more, and I know that he would give his life to see me free. There is no difference between his views and mine.

I am surprised at the conditions that the government wants to impose on me. I am not a violent man. My colleagues and I wrote in 1952 to [Daniel François] Malan asking for a round table conference to find a solution to the problems of our country, but that was ignored. When [Johannes Gerhardus] Strijdom was in power, we made the same offer. Again it was ignored. When [Hendrik] Verwoerdwas in power we asked for a national convention for all the people in South Africa to decide on their future. This, too, was in vain.

It was only then, when all other forms of resistance were no longer open to us, that we turned to armed struggle. Let Botha show that he is different to Malan, Strijdom and Verwoerd. Let him renounce violence. Let him say that he will dismantle apartheid. Let him unban the people’s organisation, the African National Congress. Let him free all who have been imprisoned, banished or exiled for their opposition to apartheid. Let him guarantee free political activity so that people may decide who will govern them.

I cherish my own freedom dearly, but I care even more for your freedom. Too many have died since I went to prison. Too many have suffered for the love of freedom. I owe it to their widows, to their orphans, to their mothers and to their fathers who have grieved and wept for them. Not only I have suffered during these long, lonely, wasted years. I am not less life-loving than you are. But I cannot sell my birthright, nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free. I am in prison as the representative of the people and of your organisation, the African National Congress, which was banned.

What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? What freedom am I being offered when I may be arrested on a pass offence? What freedom am I being offered to live my life as a family with my dear wife who remains in banishment in Brandfort? What freedom am I being offered when I must ask for permission to live in an urban area? What freedom am I being offered when I need a stamp in my pass to seek work? What freedom am I being offered when my very South African citizenship is not respected?

Only free men can negotiate. Prisoners cannot enter into contracts. Herman Toivo ja Toivo, when freed, never gave any undertaking, nor was he called upon to do so. I cannot and will not give any undertaking at a time when I and you, the people, are not free.Your freedom and mine cannot be separated. I will return.

When F. W. de Klerk signed off on Mandela’s release in 1990, he was careful to make certain that Mandela’s freedom would be unconditional.

From ‘Assisted Self-Portraits’ (2002-2005) by Anthony Luvera.

PHOTOGRAPHY’S NOT JUST DEPICTION!

There’s a fascinating discussion to be had at Aperture Gallery this Saturday December 7th. Collaboration – Revisiting the History of Photography curated by Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, and Susan Meiselas is an effort to draft the first ever timeline of collaborative photographic projects. Items on the timeline have been submitted either by members of the public or uncovered during research by Azoulay, Ewald, Meiselas and grad students from Brown University and RISD.

“The timeline includes close to 100 projects assembled in different clusters,” says the press release. “Each of these projects address a different aspect of collaboration: 1. the intimate “face to face” encounter between photographer and photographed person; 2. collaborations recognized over time; 3. collaboration as the production of alternative and common histories; 4. as a means of creating new potentialities in given political regimes of violence; 5. as a framework for collecting, preserving and studying existing images as a basis for establishing civil archives for unrecognized, endangered or oppressed communities; 6. as a vantage point to reflect on relations of co-laboring that are hidden, denied, compelled, imagined or fake.

Within the gallery space, Ewald and co. will discuss the projects and move images, quotes and archival documents belonging to the projects about the wall “as a large modular desktop.”

The day will create the first iteration of the timeline which will continue to be added to.

“In this project we seek to reconstruct the material, practical and political conditions of collaboration through photography — and of photography — through collaboration,” continues the press release. “We seek ways to foreground – and create – the tension between the collaborative process and the photographic product by reconstructing the participation of others, usually the more *silent* participants. We try to do this through the presentation of a large repertoire of types of collaborations, those which take place at the moment when a photograph is taken, or others that are understood as collaboration only later, when a photograph is reproduced and disseminated, juxtaposed to another, read by others, investigated, explored, preserved, and accumulated in an archive to create a new database.”

I applaud this revisioning of photo-practice; I only wish I was in NYC to join the discussion.

As you know, I celebrate photographers and activists who involve prisoners in the design and production of work. And I’m generally interested in photographers who have long-form discussions with their subjects … to the extent that they are no longer subjects but collaborators instead.

Photographic artists Mark Menjivar, Eliza Gregory, Gemma-Rose Turnbull and Mark Strandquist are just a few socially engaged practitioners/artists who are keen on making connections with people through image-making. They’ve also included me in their recent discussions about community engagement across the medium. I feel there’s a lot of thought currently going into finding practical responses to the old (and boring) dismissals of detached documentary photography, and into finding new methodologies for creating images.

At this point, this post is not much more than a “watch-this-space-post” so just to say, over the coming weeks, it will be interesting to see the first results from the lab. If you’re free Saturday, and in New York, this is a schedule you should pay attention to:

1:00-2:00 – Visit the open-lab + short presentations by Azoulay, Ewald and Meiselas.

2:00-2:45 – Discussion groups, one on each cluster with the participation of one of the research assistant.

2:45-4:00 – Groups’ presenting their thoughts on each grouping.

4:00-4:30 – Coffee!

4:30-6:00 – Open discussion.

6:00 – Reception.

If any of you make it down there and have the chance, please let me know what you think and thought of the day.

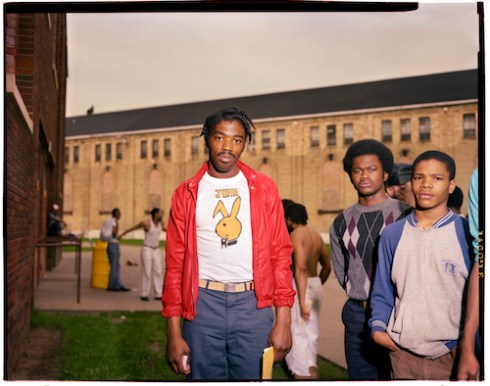

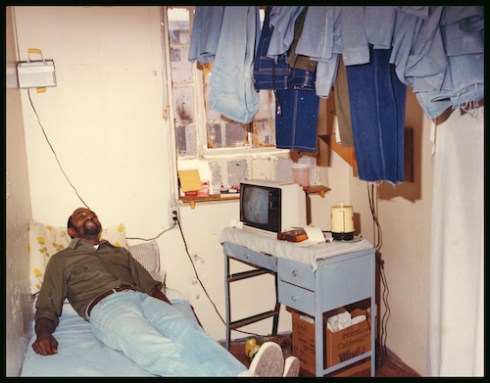

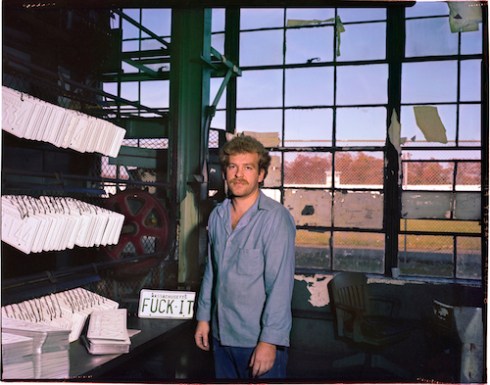

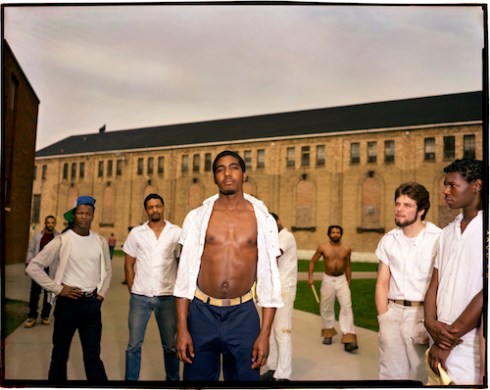

I’ve been stumbling across some mind-blowingly novel prison photographs recently. This incredible Facebook Album by Steve Milanowski fell on my radar and the colour is something special.

Milanowski photographed at three prisons during the eighties — Walpole, Massachusetts (1981, 1982); Ionia, Michigan (1984); and Jackson, Michigan (1985). In 2012, he began shooting the outside of Waupun Correctional Institution in Wisconsin. In each case, Milanowski was working independently and not on assignment.

As colourful and characterful as these images are it’s worth bearing in mind that prisons of this era were beginning to creek. Dangerous overcrowding existed in Michigan prisons in the early eighties, and Jackson in particularly was renowned as a tough prison with gangs and enforced convict codes.

These prison photographs have, up to this point, only had limited circulation. Some feature in Milanowski’s book Duplicity, others on his website. A few photographs have appeared in museum exhibitions around the country. I wanted to know more, so I dropped Steve a line with some questions.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Prison Photography (PP): Where did your interest in prisons come from?

Steve Milanowski (SM): It dates back to my childhood: my dad was an attorney in Michigan and very occasionally had clients that he had to visit in prison. When I was in 5th and 6th grades, maybe twice, he took me along (taking me out of classes) on the prison/client visits. For a 6th grader, these visits were absolutely unforgettable. Indelible. This was an environment that was utterly foreign to my existence. It was almost as if my eyes weren’t fast enough to take it all in. To a kid, nothing in the world looks like a prison.

PP: What was the purpose of your visits the these four prisons?

SM: Simply to make new photographs in places that have mostly been, in the past, photographed with visual cliche and with the perceived grittiness of black and white films.

PP: How did you gain access?

SM: My first permission was with Walpole in Massachusetts. I sent a letter to the Walpole warden; it was written on MIT stationary. I was a graduate student at MIT and I think the name helped in getting me access. I found that once one gets permission to photograph in a prison — that permission leads to more permission. I used the Walpole photographs in gaining access to Jackson and Ionia prisons. No negotiations were needed; they all gave me fairly easy access. Initially, I only asked for single-visit access.

PP: How would you characterize the atmosphere of the prisons?

SM: The atmosphere was taut, tough and difficult at most turns — very regimented and formal. In some instances, I was assigned a female escort which made my shooting more difficult because the inmates had no hesitation in shouting out awful, obscene things; and, the female escorts seemed bent on proving that they were not bothered or intimidated by these nasty shout-outs.

PP: How does this body of work relate to your other projects and your philosophy/approach to photography generally?

SM: I consider my work to be the work of a portraitist. My prison portraits are stylistically in line with the portrait work that I pursue “out in public” at public demonstrations, holiday parades, festivals, fairs, and competitions.

PP: What were the reactions of the staff to your photography?

SM: I never really sought out their reactions. My photographs did seem to always successfully get me more access though.

PP: What were the reactions of the prisoners?

SM: Never really got reactions, per se. But with each portrait, I offered a free print if they wrote me a request and visually described themselves; some inmates wrote back and praised the images. Some seemed to want to start a pen pal relationship, just because, it seemed, some inmates had few contacts with the outside world.

PP: What is your personal opinion of prisons? Have they changed since you visited in the eighties?

SM: Prisons, then and now, in America, seem to continue to be warehouses; I think most Americans are aware of the fact that we, as a nation, have one of the largest prison populations in the world — and that we incarcerate at a level that far exceeds almost all other nations.

Have prisons changed? One change I’ve noticed with great concern is the concept and use of Supermax prisons which seems to be uniquely American. With older prisons as well as Supermax prisons, we seem to never be willing to spend much money on reducing recidivism.

The conservative right loves to convey the idea that they are tough on crime — tough prisons, tough sentencing, and the idea of “throw away the key.” So, our prison populations grow, and we build more prisons than any other nation. We’ve seen the expansion. And the Democrats? They do their best to avoid being tagged as “soft on crime.”

PP: What are Americans’ feeling toward crime and punishment?

SM: Americans very much ignore prisons and prison life — unless they live near a prison where the prison is the source of some level of local employment. Americans seem to only take notice of prisons when there is a problem, an escape, a prison disturbance (that receives national media attention), or when there is some breakdown in the system.

There seems to be a real void in political or community leadership especially in the realm of education as a path to reducing crime and reducing prison populations; the idea gets plenty of lip service.

PP: What role has photography in telling publics about prisons? Is it an effective tool?

SM: I think photography can help — and be an effective tool in informing the public about prisons and who inhabits American prisons; but, I’m not sure at all that our society wants to look at prisons and prison life … its too easy to ignore.

PP: What camera and film did you use?

SM: 4×5 Linhof and 4×5 Kodak and Fuji color negative. Sometimes a Pentax 6×7 with Fuji and Kodak color negative film. And, always combining flash with ambient light.

PP: The color you introduce is unusual for prison photographs. From looking at your other work, it is clear you revel in colour portraits. Were you aware that you were making unique images; splashing color all over these darkened corners of US society?

SM: Unique images? Well you have hit on something that was a primary intention: I wanted to make photographs that told you something new. Pictures you hadn’t seen before. Prison photography is rife with cliches. I thought if I were given access to prisons, I’d make different photographs. I was not arrogant about this — just determined to make images that had not been seen before.

I was determined, self-directed and wanted to get as many photographs as I could accomplish in, typically, a 1 to 2 hour visit. I limited my talk and conversations — I was on a mission.

BIOGRAPHY

Steve Milanowski is a photographer and, with Bob Tarte, co-author of Duplicity, a monograph of his own portraits. Milanowski earned his BFA from The Cranbrook Academy of Art and his MS from The Creative Photography Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His photographs are part of the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, National Gallery of Art, The Houstin Museum of Fine Arts, The High Museum of Art, and The Polaroid Collection and numerous public collections. MoMA published his work in Celebrations and Animals; his work was also included in MoMA’s recent survey of late 20th century photography in the newly reinstalled Edward Steichen galleries.

IVY LEAGUE LAW GRADS MAKING FILMS?

Following up on Monday’s post The 20 Best American Prison Documentaries, I wanted to highlight the Visual Law Project out of Yale University.

The project runs “a year-long practicum at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School that trains law students in the art of visual advocacy — making effective arguments through film.”

I’d think being a law graduate and then a real world lawyer would be enough; one expects visual journalists or documentarians to have this sort of territory covered. Perhaps not? Never too many advocates or concerned observers, right?

There’s more answers on the FAQ page:

Q: Why should law students learn visual advocacy?

A: Visual and digital technologies have transformed the practice of law. Lawyers are using videos to present evidence, closing arguments, and victim-impact statements; advocates are making viral videos to advance public education campaigns; and scholars are debating ideas in a multimedia blogosphere. Everyone’s doing it. But no one is really teaching it — or reflecting upon it. We see training in visual advocacy — effectively evaluating and making arguments through videos and images — as a vital part of our legal education.

Of the films the VLP has produced The Worst Of The Worst is of particular interest to me. One can be lax and think that solitary confinement is a brutal practice prevalent only in California, New York, Illinois and other large states, but every state has at least one SuperMax including the seemingly genteel Connecticut.

The Worst of the Worst takes us inside Northern Correctional Institution, CT’s sole supermax prison, and includes interviews with a range of experts and administrators are interwoven with the stories of inmates and correctional officers who spend their days within the walls of Northern.

From the trailer, the treatment of the correctional officers and prisoners seems sympathetic. This gives me hope; it suggests the problem is the fabric of the facility which prohibits rehabilitation, rather than a presumption of fault or inadequacy. Prisons are toxic and often inflexible enough to capitalise on the potential of people who are caged and work within.

Check out the fledgling (est. 2011) student run Visual Law Project.

More here.

Thanks to Larissa Leclair for the tip!

Prison guards in Norway train for two-years in a special program which includes seminars on human rights, ethics and law. Warden Heidal oversees between 250 and 340 prisoners.

This week the University of Oslo admitted mass-murderer Anders Breivik into their Political Science program. It caused astonishment and chagrin for people across the globe. Understandably so. But, equally understandable is the decision, as explained by Ole Petter Ottersen, rector University of Oslo:

The fact that his application is dealt with in accordance with extant rules and regulations does not imply that Norwegians lack passion or that anger and vengefulness are absent. What it demonstrates is that our values are fundamentally different from his. […]

Having been admitted to study political science, Breivik will have to read about democracy and justice, and about how pluralism and respect for individual human rights, protection of minorities and fundamental freedoms have been instrumental for the historical development of modern Europe. Under no circumstances will Breivik be admitted to campus. But in his cell he will be given ample possibilities to reflect on his atrocities and misconceptions.

I have written before about Halden Prison — in which Breivik is held — that time leaning on the photographs of Fin Serck-Hanssen. I still hold that a prison should never alter or lower its operations to equal the depraved levels of its most infamous and criminal prisoners. As institutions, Halden Prison and the University of Oslo are both conducting themselves in ways fitting for a resolute and lawful society.

Gughi Fassino‘s photographs from Halden show us the very contemporary facilities and programs available to prisoners.

I am not interested in famous prisoners; they are famous because their crimes were extraordinary. The disproportionate amount of press coverage they get distorts the debate and distorts our impressions of what a prisoner is. I am more interested in the non-violent prisoners (a category that is proportionally much higher in the U.S.) that wallow in overcrowded prisons and don’t have access to meaningful programs.

Rehabilitation, education and vocational activities REDUCE recidivism and in turn REDUCE the financial burden to society. Men released from Halden Prison succeed at a much higher rate as compared to those released from other prisons in Norway, released from other prisons in Europe and by a distance compared to those released from U.S. prisons. Only 20% of Halden prisoners reoffend in the three years after release. The figure in the U.S. is 65-70%.

Roughly 90% of U.S. prisoners will eventually be released; they need help readjusting after years looked up and they need reason to buy into our society. We don’t need cycles of crime to persist and to pretend prison conditions aren’t the largest factor in that equation is a refusal to deal with the issue. WE deserve better prisons.

So as we look over Fassino’s photographs, let us not think about what these facilities mean for Breivik but what similar facilities could mean for the 2.3 million American prisoners and society as a whole.

View more of Fassino’s photographs here.